Buyer Preferences for Feeder Calf Traits

Cowherd owners need to understand what animal attributes affect the value of feeder calves. Periodic research identifies buyer preferences for feeder calf traits and the value of those traits. One such study in Oklahoma compared the value of feeder cattle characteristics at two time periods, October 1997 and April 1999 (Smith et al.).

Similar information on the value of feeder calf traits was generated from Oklahoma Quality Beef Network sales during the period 2001 to 2003. An earlier OSU Cooperative Extension fact sheet, AGEC-599 Price Premiums from the Oklahoma Quality Beef Network, discussed price premiums for preconditioning. Further information is reported in this Extension fact sheet on price premiums and discounts for several other feeder calf traits. The objective is to identify traits that affect the price of calves and potential marketing and management intervention strategies that should improve market prices for calves.

Oklahoma Livestock Market Data

Data were collected on feeder calves sold at Oklahoma Quality Beef Network (OQBN) sales which began in 2001. Sales were held during October to December each of the three years, 2001 to 2003. Livestock markets sponsoring OQBN sales included the following Oklahoma locations: Apache, El Reno, Enid, Holdenville, Idabel, Tulsa, Woodward, and Welch. The value of feeder calf traits was estimated for about 35,000 feeder calves sold at twenty sales over the three-year period.

Feeder calf traits were estimated in a manner similar to previous research (Avent, Ward, and Lalman). A regression model was estimated for each sale each year. Statistically significant premiums and discounts for feeder calf traits were summarized across sales within each year, then across years to arrive at mean values for each feeder calf trait.

Feeder Calf Traits and Value

Traits discussed include weight, gender, frame, muscling, condition, horns, and health. Two closely related market variables, sale lot uniformity and sale lot size, are also discussed. Nearly all of these feeder calf characteristics are directly or indirectly controlled by the cow-calf producer. Table 1 presents a summary of the results. Note that the discussion of each feeder calf trait is in the context of all other factors having been accounted for in the regression equation. In other words, the regression equation estimated the price effect for one trait while the effects from all other feeder calf characteristics were held constant.

Price differences reflect what buyers actually paid for feeder calves. Buyers’ prices are dependent on the number of calves available with particular characteristics at each sale as well as market conditions, number of competing buyers, and buyers’ personal preferences. Thus, premiums and discounts varied within and between sales as well as within and between years. Table 1 illustrates the year-to-year average value for feeder calf traits revealed from prices paid by buyers over several sales and three years time.

Table 1. Estimated value ($/cwt.) of several feeder cattle traits from twenty OQBN sales, 2001-2003

| Feeder Cattle Trait | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | Average 2001-2003 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Steers | Base | Base | Base | Base |

| Heifers | -8.598 | -8.002 | -9.187 | -8.596 |

| Bulls, mixed steers/heifers | -4.555 | -5.433 | -4.3 | -4.763 |

| Frame | ||||

| Large frame | 0.174 | -1.674 | -3.524 | -1.675 |

| Medium frame | Base | Base | Base | Base |

| Small frame | -13.642 | NA | 3.154 | -3.496 |

| Muscling | ||||

| Heavy muscled | 1.986 | 2.035 | -2.475 | 0.515 |

| Moderately muscled | Base | Base | Base | Base |

| Thin muscled | -11.391 | -7.224 | NA | -6.205 |

| Condition | ||||

| Thin flesh | 2.731 | -2.419 | 3.754 | 1.355 |

| Average flesh | Base | Base | Base | Base |

| Fleshy or fat | -3.024 | -3.327 | 1.025 | -1.775 |

| Horns | ||||

| No horns | Base | Base | Base | Base |

| Horns, mixed | NA | -4.673 | NA | -1.558 |

| Health | ||||

| Healthy | Base | Base | Base | Base |

| Not healthy | -5.789 | -12.115 | -7.82 | -8.575 |

| Uniformity | ||||

| Uniform lot | Base | Base | Base | Base |

| Uneven lot | -1.948 | -3.154 | -3.174 | -1.908 |

Weight

Feeder calf prices decline as calf weight increases. This relationship is generally well-known by cattlemen and confirmed consistently in research. The price difference between weights of calves is commonly referred to by many terms; price slide, price rollback, and negative margin, among others. The magnitude of the decline in price as weight increases differs with market conditions. Thus, the weight-price relationship changes over time. Over the 2001-2003 OQBN sales, the weight-price relationship was significant in seventeen of the twenty OQBN sales.

Gender

Nearly all previous research shows economically important feeder calf price differences among steers, heifers, and bulls. Usually steer calves are considered the base (as noted in Table 1) or the standard for comparison. Significant price differences between steers and heifers were found in all twenty OQBN sales over the 2001-2003 period. Heifer calves were consistently discounted relative to steers, from $8.00/cwt. in 2002 to $9.19/cwt. in 2003. Buyers discount heifer calves because heifers present more potential management problems and heifers do not perform as well as steers. On average, the discount was $8.60/cwt. for the three years. Price differences between heifers vs. steers were larger in fall sales in 1997 and smaller in spring sales in 1999 (Smith et al.) than was found during fall sales over the 2001-2003 period in this study.

Bull calves and mixed gender lots of calves were discounted relative to steers in seven sales. When bull calves must be castrated at 6-10 months of age, animal performance declines. Therefore, buyers typically discount bull calves. The discount for bull calves and mixed gender lots ranged from $4.30/cwt. to $5.43/cwt. with an average discount of $4.76/cwt. This price difference was slightly larger than in either 1997 or 1999 (Smith et al.).

Frame Size

Between the 1970s and 1990s, the mature height (frame score) of beef cattle increased substantially; in turn producing larger framed calves. Additionally, the mature size of fed cattle increased. Since the early 1990s, according to one of the major cattle breed organizations, the mature height of breeding animals has stabilized. A question remains as to whether or not larger framed calves are more profitable than smaller framed animals. Research suggests there are performance differences among feeder calf frame sizes, both in feedlot performance and in carcass attributes (Baggett, Ward, and Childs). Expected performance differences form the basis for the official U.S. Department of Agriculture feeder cattle grades. However, the key to profitability for buyers is how much to pay for calves of one frame size vs. calves with another frame size.

Buyers paid higher prices for calves classified as large frame compared with medium and small frame calves both in 1997 and 1999 (Smith et al.). Larger frame calves are expected to gain faster and produce larger carcasses when harvested. For the 2001-2003 period, results were mixed (Table 1). Buyers paid a slight premium for large frame calves in two sales in 2001 ($0.17/cwt.), but discounted large frame calves in one sale in 2002 and another sale in 2003 (from $1.67 to $3.52/cwt.). Small frame calves were discounted severely in three sales in 2001 ($13.64/cwt.) but buyers paid a premium for small frame calves in one sale in 2003 ($3.15/cwt.). Based on the average over the three-year period, large frame calves received a small discount ($1.68/cwt.) compared with medium frame calves, while small frame calves were discounted more heavily ($3.50/cwt.).

Muscling

Breeding programs also frequently emphasize muscling of calves. Muscling affects carcass weight at maturity and the yield grade of fed cattle carcasses. Buyers paid a premium for heavily muscled calves both in 1997 and 1999 and in both years discounted thin or lightly muscled calves (Smith et al.).

For OQBN sales in 2001-2003, results were again mixed (Table 1). Buyers paid a premium for heavily muscled calves in two sales in 2001 ($1.99/cwt.) and two sales in 2002 ($2.04/cwt.). However, buyers discounted heavy muscled calves in one sale in 2003 ($2.48), which was not expected. Thin muscled calves were discounted in four sales in 2001 ($11.39/cwt.) and three sales in 2002 ($7.22/cwt.). Based on the average over the three years, buyers paid a small premium ($0.52/cwt.) for heavily muscled calves and a much larger discount ($6.20/cwt.) for thinly muscled calves.

Condition

Condition of feeder calves can be influenced by several factors, including transportation, handling, and weighing conditions associated with the selling process. In 1997 and 1999, buyers preferred average conditioned calves, discounting both thin and fat calves (Smith et al.).

At OQBN sales, buyers paid a premium for thin fleshed or poor-conditioned calves in one sale in 2001 ($2.73/cwt.) and two sales in 2003 ($3.75/cwt.), but discounted thin fleshed calves in one sale in 2002 ($2.42/cwt.) (Table 1). Fleshy or fat calves were discounted in three sales in 2001 ($3.02/cwt.) and three sales in 2002 ($3.33/cwt.). However, buyers paid a small premium in two sales in 2003 for fleshy calves ($1.02/cwt.). How buyers value fleshiness depends in part on whether or not they expect compensatory gains from thin fleshed calves and the health or thriftiness of the calves. Based on the three-year averages, thin fleshed calves received a premium of $1.36/cwt. over the three-year period, while fleshy or fat calves were discounted $1.78/cwt.

Horns

Polled feeder calves normally receive a price premium when compared with horned calves, as was the case in Oklahoma both in 1997 and 1999 (Smith et al.). At OQBN sales, horned calves were not discounted in many sales. Buyers on average discounted horned calves $1.56/cwt. compared with genetically polled or dehorned and healed calves (Table 1). That amount was less than was found in 1997 or 1999.

Health

Of all feeder calf characteristics, health-related attributes often have the most profound effect on price. Unhealthy traits generally translate into severe price discounts. Buyers watch closely for sick or unhealthy calves. In 1997 and 1999, discounts for various categories of unhealthy calves were larger than for any other feeder cattle trait (Smith et al.).

Buyers discounted unhealthy calves at one OQBN sale in 2001 ($5.79/cwt.), four sales in 2002 ($12.11/cwt.), and one sale in 2003 ($7.82/cwt.) (Table 1). In nearly all cases, the unhealthy calves were not enrolled in the OQBN preconditioning program. The average discount was $8.58/cwt. for unhealthy or unhealthy appearing calves over the three-year period. Health is an important trait in marketing feeder calves and one reason why preconditioning programs are increasing in importance throughout the U.S.

Uniformity

Sale lots can be uniform or non-uniform from many standpoints, breed combinations, frame, muscling, weight, etc. Buyers can typically visually determine to some extent whether or not a sale lot of calves appear uniform. Typically, buyers pay a premium for uniform sale lots and discount non-uniform lots. Smith et al. found this result in 1997, but buyers paid little difference for uniform vs. non-uniform lots in 1999.

Uniformity was valued by buyers in nine OQBN sales during 2001-2003 (Table 1). Buyers paid a premium ranging from $1.95/cwt. in 2001 to $3.17/cwt. in 2003, and averaging $1.91/cwt. for uniform sale lots over the three-year period.

Lot Size

Buyers frequently perform a pooling function in the marketplace, whether in filling orders for stocker producers and cattle feedlot managers or in buying calves for themselves. Buyers often purchase small sale lots of cattle and pool them into larger, oftentimes truckload size, lots for more efficient shipping and to fill pre-established pasture and pen sizes. The pooling function is made easier if buyers can purchase larger sale lots. As a result, buyers typically pay a premium for larger lots. Larger sale lots in some cases mean calves originated with a single owner, implying more uniform health and nutritional management. Those calves may be associated with less stress and fewer health problems, so they are worth more to buyers.

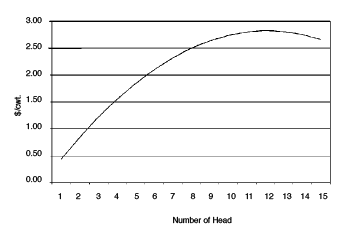

Figure 1 shows the price premiums paid by buyers in fifteen OQBN sales for the three-year period, 2001-2003. Even increasing sale lot size from 1 head to 10-15 head can mean meaningfully higher prices, averaging about $2.50/cwt. over the 2001-2003 period. Price premiums paid by buyers peaked in 2001 for lot sizes of 50 head and in 2003 for lot sizes of 45 head. However, in 2002, premiums were paid only for lots up to 10 head in size. Thus, the premiums shown in Figure 1 are not as large for larger lot sizes as found in some previous research (Avent, Ward, and Lalman).

Figure 1. Price Premium for Lot Size, 2001-2003 Average.

Summary and Conclusions

Buyers of feeder calves reveal their preferences for feeder calf characteristics through the prices they pay. The value of various traits can vary widely from sale to sale and depend on market conditions. However, over time, a reasonably good estimate of what buyers prefer can be determined. The exact value will still vary but cow-calf producers can determine what is important to buyers and use that information as a guide in making management and marketing decisions.

Buyer preferences were estimated with data from twenty Oklahoma Quality Beef Network sales during 2001, 2002, and 2003. The following summarizes some of the findings.

Buyers paid a premium for:

- steer calves compared with heifers, bulls, or mixed gender sale lots;

- medium frame calves compared with large and small frame calves;

- heavy muscled calves compared with moderately and thin muscled calves;

- thin fleshed calves compared with average and fleshy or fat calves;

- polled or dehorned and healed calves compared with horned calves;

- healthy calves compared with unhealthy or unhealthy appearing calves;

- uniform sale lots compared with non-uniform lots;

- and larger sale lots, even 10-15 head, compared with single-head lots.

Cow-calf producers have the ability to influence and manage nearly all of the feeder calf traits identified in the above list to receive the maximum value possible from their calves.

References

Avent, R. Keith, Clement E. Ward, and David L. Lalman. “Market Valuation of Preconditioning Feeder Calves.” Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics 36,1(2004):173-83.

Baggett, Hub B. IV, Clement E. Ward, and M.Dan Childs. “Effects of Feeder Cattle Grades on Performance and Net Returns.” Journal of the Society of Farm Managers and Rural Apprisers 68(2004):1-6.

Smith, S. C., D. R. Gill, C. Bess III., B. Carter, B. Gardner, Z. Prawl, T. Stovall, J., Wagner. “Effect of Selected Characteristics on the Sale Price of Feeder Cattle in Eastern Oklahoma.” Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service. Fact Sheet E-955, 2000.

Clement E. Ward

Professor and Extension Economist

Chandra D. Ratcliff

Graduate Research Assistant

David L. Lalman

Associate Professor and Extension Beef Cattle Specialist