To Be or Not to Be: That is the Gluten-Free Marketing Question

At the turn of the 21st century, the letters “GF” on a restaurant menu would have probably confused a majority of patrons. These letters, of course, stand for “gluten-free.” Today, the gluten-free market is a multi-billion-dollar industry – although the definition of gluten-free and its applicability to food markets is somewhat contentious.

What does gluten-free mean?

Gluten is a mixture of proteins found in a small group of grains: wheat, rye, barley and any/all hybrids of these three grains (e.g. triticale, a cross between wheat and rye). Any products that include flour or whole grains from these plants also will contain gluten, unless steps have been taken to remove enough gluten so the final product contains less than 20 parts per million (ppm) of gluten as per the requirements in the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) gluten-free labeling guidelines (see Federal Register / Vol. 78, No. 150 for more details). For example, a cornbread batter mix that is primarily made of corn meal but also includes wheat flour could not be labeled as gluten-free. However, a product made solely of corn meal that can guarantee it contains less than 20 ppm of gluten can be labeled as gluten-free.

Close to 3 million Americans have been diagnosed with celiac disease, which is basically an allergy to the gluten protein. Sufferers of this disease experience inflammation in the lining of the small intestine due to gluten consumption, resulting in less nutrients being absorbed into the bloodstream. Symptoms include diarrhea, constipation, bloating and pain.

In recent years, millions of Americans have exhibited signs of gluten intolerance and gluten sensitivity. Gluten intolerant/sensitive individuals may or may not experience symptoms similar to those associated with celiac disease, but they do not experience damage to the small intestine. This rise in gluten intolerance/sensitivity has contributed to increased adoption of a mostly gluten-free diet.

To attract the attention of these consumer segments, many companies market their foods as gluten-free. Any number of products may be certified as gluten-free by a third-party source (e.g. the Gluten-Free Certification Organization) as long as the products meet the FDA definition of gluten free as foods NOT containing the following:

- An ingredient that is any type of wheat, rye, barley or a cross of these grains.

- An ingredient derived from these grains and that has not been processed to remove gluten.

- An ingredient derived from these grains that has been processed to remove most of the gluten, but the resulting product still contains 20 or more parts per million (ppm) of gluten.

Most food items do not contain gluten-based grains, yet many food and beverage companies place a gluten-free claim on their products that are inherently gluten-free for marketing purposes. Examples include gluten-free labels on eggs, meats, vegetables, dairy products, soft drinks, orange juice and even bottled water. This marketing tactic has allowed retailers to sell products bearing the gluten-free claim for a 100% premium (Lee et al., 2007).

Market Trends

Many consumer surveys suggest a gluten-free diet is one of the most popular U.S. health food trends in recent years (Miller, 2016). This is not due to an increase in diagnosed cases of celiac disease, which remains stable at around 1% of the U.S. population (about 3 million people), but rather increased rates of gluten sensitivity/intolerance among (12-18 million) U.S. citizens and the perception food products with a gluten-free label are healthier than other products (Navarro, 2016). This common perception is the leading argument the 5.4 million Americans without celiac disease provide for adhering to a gluten-free diet (Choung et al., 2017; Mintel, 2016).

Food companies and retailers have employed a variety of marketing strategies emphasizing gluten-free products in response to the popularity of the gluten-free diet. However, the recent interest in purchasing gluten-free food products has been described as a fad (Reilly, 2016), so redesigning an existing marketing campaign to emphasize gluten-free may or may not result in long-term payback benefits for participating food industry firms.

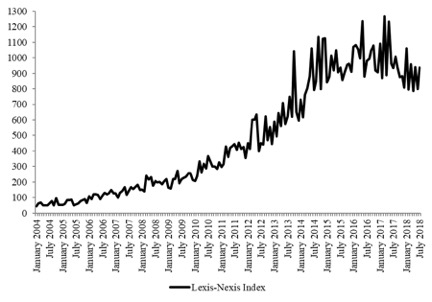

Fad or not, the gluten-free market has been valued at more than $6.6 billion (Talley and Walker, 2016). The popularity of books such as Wheat Belly (Davis, 2011) and Grain Brain (Perlmutter, 2013) have helped spur consumer interest in gluten-free products. The increase in media stories/coverage of gluten-free products also corresponds with the increase in gluten-free food offerings (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Monthly Lexis-Nexis search results for number of media stories referring to gluten-free, 2004-2018.

According to the USDA Economic Research Service (ERS, 2019), approximately 1,200 new products made gluten-free claims in 2009. By 2016, more than 6,100 new food and beverage products included gluten-free claims. Roughly one-fourth (26%) of these new products were in the snacks segment of the industry, but sauces/seasonings, dairy products and processed fish/meat/egg categories had at least 12% of the new gluten-free product introductions (Figure 2).

Figure 2. U.S. gluten-free product introductions, 2016-18 (source: Mintel GNPD, 2018).

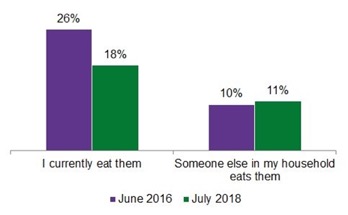

Interestingly, the number of customers purchasing gluten-free alternatives in lieu of traditional gluten-containing foods has begun to decline (Figure 3) even though gluten-free introductions have surpassed almost all other forms of “free” food product placements (e.g. GMO-free, artificial ingredient-free, etc.) in the market (ERS, 2019). Several possibilities exist for the stabilization of the gluten-free market:

- Only half of consumers trust a food with a gluten-free claim is, in fact, actually free of gluten (Mintel 2018).

- Recently published medical research suggests fructan, a polymer of fructose molecules, may be the cause of some non-celiac gluten sensitivities. Additional research also suggests gluten-free foods might have a lower nutritional value relative to their traditional gluten-containing counterparts.

- The blatant use of gluten-free claims on food products not inherently containing gluten by food manufacturers has lowered the perceived value of a gluten-free claim.

- There appears to be growing public backlash towards individuals without gluten issues who adhere to gluten-free diets. This may be due to their gluten-free demands placing an undue burden on other household members or friends who are forced to adjust their dining experiences to cater to the gluten-free dieter.

Figure 3. Consumption of gluten-free alternatives, June 2016 vs. July 2018 (source: 2,000 internet user survey, Lightspeed/Mintel)

Does a Gluten-Free Label Help Sell Food Products?

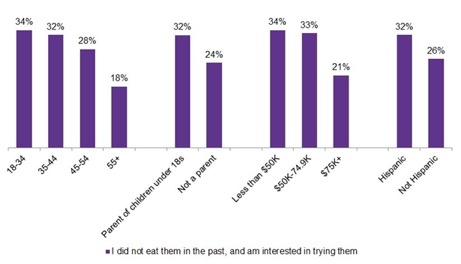

According to Mintel (2018), there remains a large segment of the population that does not consume gluten-free foods but is interested in trying them (Figure 4). Mintel’s survey suggests this sentiment is more prevalent in adults under the age of 45, especially those who are parents of children under the age of 18. Interestingly, the survey also suggests Hispanics are more inclined to be in this consumer segment than non-Hispanics.

Figure 4. Consumers who do not eat gluten-free foods, but are interested in trying them (source: Lightspeed/Mintel, 2018).

Although a strong consumer segment remains for gluten-free foods, the previously highlighted trends – declining number of new gluten-free product introductions each year and a recent drop-off in the number of media articles about gluten-free foods – suggest a leveling-off of the segment’s marketing “wow” factor. Ates (2019) found while media publications about gluten-free foods and trends do impact demand for various products, the impacts are delayed and short lived. This is consistent with Mintel’s (2018) finding that even though prices of gluten-free products have declined, the number of new product introductions and waning consumer interest suggest either a passing fad or – at the very least – consumers’ interests in new gluten-free product introductions has passed its peak.

The take-away from these findings is, while gluten-free claims still generate levels of consumer interest and boost self-image (e.g. healthier, safer, etc.), the over-abundance of gluten-free claims made by food companies has somewhat lessened the consumer purchasing impacts. Food marketers of gluten-free foods still may find benefit in using the claim but the addition of other claims – such as “all natural,” “no preservatives,” “high protein,” “low sugar,” etc., also may help spur consumer interest in their product offerings.

For more information about food marketing trends and gluten-free product development, please contact the Oklahoma State University Robert M. Kerr Food & Agricultural Products Center (FAPC). FAPC’s food scientists and business/marketing specialists have extensive experience in the formulation and promotion of gluten-free, organic, and locally grown/processed food products. Call (405) 744-6071 for more information.

References

- Ates, A.M. 2019. Three Essays on U.S. Household Food and Diet Preferences. Doctoral dissertation in Agricultural Economics, Oklahoma State University.

- Choung, R.K, Unalp-Arida, A., Ruhl, C.E., Branter, T.L., Everhart, J.E., and J.A. Murray. 2017. “Less Hidden Celiac Disease but Increased Gluten Avoidance Without a Diagnosis in the United States: Findings From the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys From 2009 to 2014.” Mayo Clinic Proceedings 92(1):30-38.

- Davis, W. 2011. Wheat Belly. New York: Rodale Books.

- Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2019. New Products. Washington DC. Accessed August 28, 2019, online at https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-markets-prices/processing-marketing/new-products/.

- Federal Register, U.S. 2013. “Food Labeling: Gluten-Free Labeling of Foods.” 21 CFR 101 as reported in 78 FR 47154, pp. 47154-47179, August 5, 2013. Accessed September 30, 2019, online at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2013/08/05/2013-18813/food-labeling-gluten-free-labeling-of-foods.

- Miller, D. M. 2016. “Maybe It’s Not the Gluten.” Journal of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine 176(11):1717-1718.

- Mintel Group, Ltd. 2018. Gluten-Free Foods – US: October 2018. Market research report available for purchase from www.mintel.com.

- Perlmutter, D.H. 2013. Grain Brain. New York: Little, Brown and Company.

- Reilly, N.R. 2016. “The Gluten-Free Diet: Recognizing Fact, Fiction, and Fad.” The Journal of Pediatrics 175:206-210.

- Talley, N.J., and M.M. Walker. 2016. “Celiac Disease and Nonceliac Gluten or Wheat Sensitivity: The Risks and Benefits of Diagnosis.” Journal of American Medical Association Internal Medicine 177(5):615-616.

Aaron Ates

Managing Economist, Berkeley Research Group,LLC

Rodney Holcomb

Food Industry Economist, Oklahoma State University

Parker Terrell

Student Researcher, Oklahoma State University