Rootstocks for Grape Production

- Jump To:

- Own-roots

- Rootstocks

- Nematodes

- Phylloxera

- Galls

As with any agricultural venture, proper planning is the first step to a successful vineyard. Before establishing a new vineyard, potential problems should be considered and steps taken to avoid falling victim to costly and long lasting mistakes.

One commonly asked question is “should I use grafted plants or own-rooted plants”? There is no simple answer. Each site and vineyard has unique situations that need to be well thought out before an answer can be given.

What is the difference between an own-rooted and grafted vine? An own-rooted plant is simply taking a cutting from one plant and rooting it to make another genetically identical plant. Therefore, if the top portion of the plant dies, and the plant sprouts from the roots, the same type of plant will reemerge.

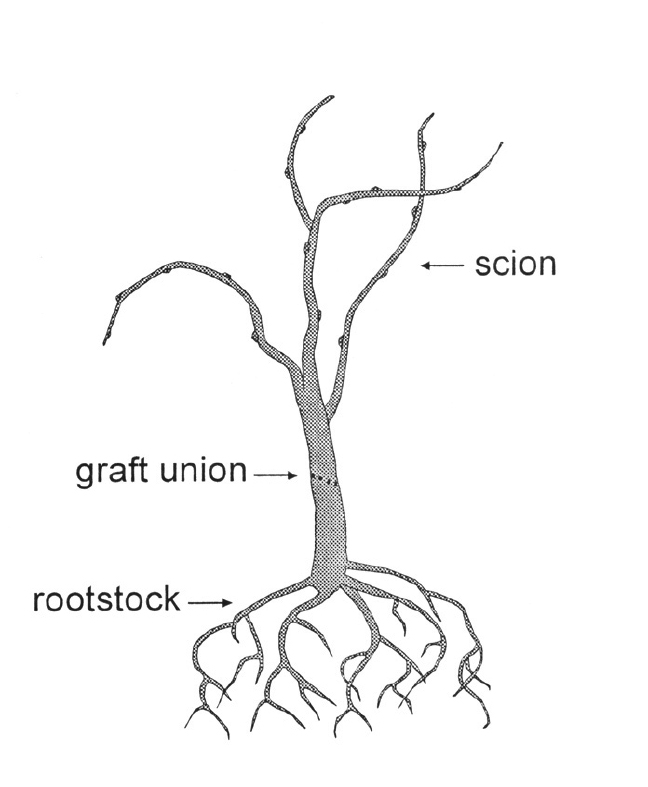

A grafted plant is made up of two plants. It is essentially joining a root portion (rootstock) with the budwood (scion) from another plant. If the scion dies and the plant re-grows from the roots, the reemerging vine will be the undesirable rootstock rather than the scion (usually a variety).

Figure 1. The scion is grafted onto the rootstock, creating a graft union between the two plants.

Before selecting an own-rooted or grafted plant there are several factors to consider. First, a vineyard should have well-drained, deep soils with a minimum of 2 feet to 3 feet of soil depth before hitting water, rock, or a hardpan. Consult your county soil survey to determine the soil type in the vineyard location. A sandy soil will be more prone to nematodes and dry out quicker than a tight clay soil. Clay soils can be too wet, not allowing water to drain and starving the roots of oxygen. An important tool in designing a vineyard is soil sampling. Soil samples should be taken in late fall and analyzed for nutrient and pH levels, as well as nematode populations. A soil sample can only be helpful if taken correctly. Consult OSU Extension fact sheet PSS-2207, “How to Get a Good Soil Sample,” for detailed directions. Local county extension educators can assist with soil or water samples and many other management issues. Soil sample recommendations for nutrients and pH adjustments, except nitrogen, should be implemented before planting the vines. The Plant Disease & Insect Diagnostic Lab at OSU can furnish information for proper nematode sampling and analysis. Results from soil samples for nutrition, pH and nematodes plus the soil type will allow an informed decision.

Why would an own-rooted plant be a better option to plant in a vineyard? Both types of plants have advantages and disadvantages.

Own-roots

Because less time and labor is involved in growing an own-rooted plant, initial plant costs are much lower. Nurseries can produce own-rooted plants in the same year that they were started; whereas, grafted plants may be at the nursery for one or two years.

In areas where freeze damage is likely, an own-rooted plant is the best choice. Avoiding the cost of replacing grafted plants or re-budding the surviving rootstocks can be eliminated. Own-rooted vineyards can be re-established sooner by using root suckers to begin new plants.

Own-rooted plants have a tendency to be less vigorous than grafted plants. If the vineyard site is very fertile with ideal soil conditions, an own-rooted plant might be the best choice to avoid too much vigor. However, if the vineyard is less than ideal or has potential soil problems such as high pH or salinity levels, a rootstock can be used to compensate for certain site limitations.

Rootstocks

Rootstocks were first used in European vineyards in the late 1800s to combat devastating phylloxera outbreaks. The vineyards began to use phylloxera resistant grape plants as rootstocks. These plants were native to North America, where the pest was naturally occurring. Today, rootstocks can be helpful in vineyards that have limiting factors. Rootstocks can be used to improve vigor, increase production, and help sustain the health or survival of the vineyard. Vinifera and some French-American hybrid grapes will benefit from rootstock use. Rootstocks may increase winter hardiness due to healthier less stressed vines. Careful consideration should be given to match the rootstock characteristics with the site limitations, therefore taking full advantage of the rootstock. It is important to remember that each rootstock may interact differently with different cultivars.

Rootstocks commonly used are Vitis species selected from native areas or hybrids that use native species to form new rootstocks. When two species are crossed, they normally exhibit characteristics of both species. Some of the most common are Vitis rupestris, V. riparia, V. berlandieri, V. x champinii, and V. vinifera. An understanding of the native environment of these species can give clues to their potential adaptation to other areas.

Riparian and drought hardy rootstocks

Riparian is a description for areas that border river banks. Vitis riparia grows in riparian habitats, alluvial soils, climbs trees, and tolerates wetter areas (Table 1). It has shallow roots, lower vigor compared to other species, and resists phylloxera. Originating in colder areas, the V. riparia is often more cold hardy than other species.

Vitis rupestris is found in Texas and Arkansas along rocky creek beds with a shrub-like growth habit. They are deep rooted, drought tolerant, and resist phylloxera (Table 1). However, the species has variable nematode resistance from plant to plant. ‘St. George’ is an example of a V. rupestris rootstock (Table 2).

Because V. riparia and V. rupestris are both easy to graft and root, they are often used in crosses to transfer these traits to less than nursery-friendly rootstocks.

Vitis berlandieri is found in Texas limestone areas. It is usually deep-rooted with some drought tolerance, and well adapted to high pH soils (Table 1). V. berlandieri is difficult to root and is used in crosses with other species.

Table 1. Characteristics of Vitis grape rootstocks and adaptability.

| Type | Vigor | Root System | Phylloxera resistance | Nematode resistance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V. riparia | low | shallow | resistant | variable | |

| V. rupestris | high | deep | resistant | variable | |

| V. berlandieri | low | deep | variable | some | |

| V. x champinii | high | deep | moderate | resistant | |

| V. x champinii x (V. solonis x V. othello) |

mod-high | moderate | ? | good | |

| V. riparia x V. rupestris |

low-mod | moderate | resistant | variable | |

| V. berlandieri x V. riparia |

mod | shallow | good | fair | |

| V. berlandieri x V. rupestris |

high | deep | good | poor |

| Type | Drought tolerance | Alkalinity tolerance | Adaption to wet conditions | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V. riparia | low | low | high | speeds maturity | |

| V. rupestris | tolerant | variable | low | shrub-like growth | |

| V. berlandieri | moderate | high | moderate | - | |

| V. x champinii | high | good | moderate | increase K | |

| V. x champinii x (V. solonis x V. othello) |

moderate | ? | low | - | |

| V. riparia x V. rupestris |

low | low | good | - | |

| V. berlandieri x V. riparia |

low | fair | good | most common | |

| V. berlandieri x V. rupestris |

good | moderate | variable | well-drained soils, hillsides |

V. x champinii is found in central Texas growing under very harsh conditions. V. x champinii survive in droughty areas with poor soils, so when planted in ideal sites with irrigation, it may be overly vigorous. These rootstocks are also sometimes less cold hardy.

The European grape species, V. vinifera exhibits some of the most tolerance to drought, salinity and calcareous soils, but is extremely susceptible to phylloxera. Because of the many benefits, V. vinifera are often used in crosses. Both ‘Harmony’ and ‘Freedom’ have V. vinifera parentage.

Tables 1 and 2 present the adaptability of rootstocks to some of the conditions faced when choosing a rootstock. Table 2 selections have been established in demonstration plots at the Oklahoma Pecan and Fruit Research Station.

If soil sample results show extremely high nutrient levels, a less vigorous rootstock or own-rooted plant should be used. Too much vigor can lead to excessive vegetation, resulting in fewer grapes, shading, and reduced quality. The rootstock 3309 Couderc (3309C) has lower growth rates than other choices.

If vineyard soils are very heavy and hold too much moisture, a rootstock with a shallow root system such as 3309C may be beneficial just as a deep-rooted rootstock will be valuable in a sandy, droughty soil. Options for drought tolerant soils would be 110 Richter, 1103 Paulsen, and 140 Ruggeri. These three rootstocks can become too vigorous in well-irrigated vineyards.

There are several rootstocks for use in soils with high pH levels. In some areas these high pH soils have problems with cotton root rot and iron chlorosis. Rootstocks with parentage from the V. berlandieri or V. x champinii species would work well for high pH soils. Areas with salt accumulation can be planted with rootstocks that compensate for increased salinity. The 140 Ruggeri rootstock is a good choice to use in areas with elevated salinity levels.

Nematodes

Nematodes are microscopic worms that feed on roots. They reduce the plants ability to take up water. Nematodes can especially be a problem in sandier soils. Many of the rootstocks have some tolerance or resistance to one or more types of nematodes. There are three main critical nematodes for grapes; root knot, root lesion, and dagger. Root knot nematodes form small knots or bumps on the root system. Both the root knot and root lesion nematodes cause a slow decline in vine health. When purchasing new vines, inspect carefully for infection and refuse shipment if detected. The dagger nematode is a carrier for fan leaf and other viruses. Freedom, Harmony, and Dog Ridge are rootstocks with good root knot nematode resistance. Vines with V. x champinii heritage have excellent overall nematode resistance. In an area with high nematode populations, an own-rooted plant may not survive.

Phylloxera

Phylloxera (root louse) are small insects that feed on the roots of grapes. They weaken and can eventually kill the vine. In many grape growing regions, phylloxera is so devastating that plants can only be grown on rootstocks that are resistant to this pest. If resistant rootstocks were not available, these vineyards would not survive. Plants grafted to V. rupestris or V. riparia have excellent resistance to phylloxera. Phylloxera is not currently a problem in Oklahoma, but some neighboring states face this obstacle.

Galls

Another potential problem when using rootstocks is the bacterial infection known as crown gall. Because of Oklahoma’s fluctuating temperatures, rootstocks are more prone to winter injury. This injury provides a site for infection to occur. Galls are usually formed at the graft union. If crown gall could be a possible problem, 3309C is a good choice. The cultivar 110R is more susceptible to crown gall.

Grafted plants require more labor because graft unions should be covered with mulch or soil before freezing temperatures occur in the fall, and removed after the threat of freeze injury has passed in the spring. Ideally, covering the graft union should be done annually for the first five seasons.

There are many rootstocks available at the nurseries, and new crosses are continually being evaluated. The rootstocks listed in Table 2 are not the only possible choices. They have been planted in central Oklahoma and tested since 2001, with more data being collected each year.

Only after proper evaluation can it be determined if a rootstock is needed. Each site and vineyard is unique. With Oklahoma’s variable weather conditions in both the spring and fall, chances of freeze injury can be high. Replacing or re-grafting vines is costly both in time and money, therefore prudent consideration should be used before a decision is made.

Table 2. Characteristics of specific grape rootstocks tested at Perkins, OK and their adaptability.

| Cultivar | Parentage | Vigor | Phylloxera resistance | Nematode resistance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5BB | V. berlandieri x V. riparia |

high | excellent | moderate |

| 110R | V. berlandieri x V. rupestris |

high | good | low |

| 1103P | V. berlandieri x V. rupestris |

high | good | low |

| 3309C | V. riparia x V. rupestris |

low-mod | good | moderate |

| 140R | V. berlandieri x V. rupestris |

high | excellent | low |

| Freedom | V. x champinii x (V. solonis x V. othello) |

mod-high | moderately susceptible |

excellent |

| St. George | V. rupestris | high | excellent | some |

| Cultivar | Drought tolerance | Alkalinity tolerance | Tolerance | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5BB | low | good | variable | cotton root rot resistant |

| 110R | high | good | moderate | delay maturity |

| 1103P | moderate | good | moderate | - |

| 3309C | low | low | low | crown gall resistant |

| 140R | excellent | good | good | crown gall susceptible |

| Freedom | low | ? | low | - |

| St. George | some | good | moderate | suckers |