Pecan Crop Load Management

Would consistent yields of high quality nuts benefit your pecan production and marketing

program? Yield and quality variation affect all pecan producers. However, growers

managing high-yielding, large-fruited cultivars for retail sales often suffer the

greatest losses from yield and quality variation. Long-term success in retail sales

is based on customer satisfaction and repeat business. Customers remember high quality

but they also remember, perhaps even longer, poorly filled pecans purchased at an

orchard’s retail outlet or received in a mail-order package.

The effect of yield and quality variation on wholesale operations is probably less

dramatic but no less important. Growers are paid a price dependent upon the national

market and the quality of their pecans. Highest quality demands the highest price.

Similar to retail sales, wholesale buyers remember producers with dependable yields

of consistently high quality nuts and reward that in the long run.

Properly practiced pecan fruit thinning (i.e., crop load management) can help ensure consistent yields of high quality nuts and reduce the pecan tree’s tendency toward alternate bearing.

Alternate Bearing

Alternate bearing refers to the tendency of pecan trees to follow a high production

year with one or more years of relatively low production. Intensive management reduces

the natural tendency of pecan trees toward alternate bearing.

Pecan cultivars vary in their tendency toward alternate bearing. Those that yield

the most in the shortest time after establishment also tend to be the most severe

alternate bearers. Researchers are not certain about the causes of alternate bearing.

Flower initiation and development in pecan is controlled by an interaction of several

factors including carbohydrate reserves and a balance of plant hormones. Flowers

that produce next year’s crop are initiated during the time this year’s crop is maturing.

Therefore, stress during flower initiation affects next year’s crop.

Excess fruit load causes several problems in addition to alternate bearing. Nuts

produced by heavy fruiting trees usually have poorly developed kernels of little or

no value. This is especially true in large fruited cultivars and those with several

nuts per cluster.

Overbearing also makes trees more susceptible to cold damage as well as shuck disorders

such as stick-tights and shuck decline. Another obvious effect of overbearing is

tree limb breakage from excess weight. This is a significant problem on the relatively

new high-yielding cultivars that tend to have brittle wood, those that are poorly

trained, and those exposed to wind storms during heavy load years.

A less obvious impact of alternate bearing is its effect on cash flow projections. This frequently makes pecan production ventures less attractive to lending agencies.

Fruit Thinning Benefits

Through the process of photosynthesis, leaves convert water and carbon dioxide into

carbohydrates needed by pecan trees for growth, flowering, and nut development. The

more leaves the tree has for each nut, the greater the chance that adequate carbohydrates

will be available for both tree growth and nut production. In fact, research done

in 1934 on Moore pecan showed that at least 8 to 10 functional leaves are needed to

adequately fill one nut. Large fruited cultivars, such as Mohawk, will require even

more leaves per nut. Increased problems with over production and poor fruit quality

as trees mature are related to a decrease in the number of leaves per fruit, especially

in heavy crop years.

The apple and peach industries have long recognized the need to remove part of the

crop to assure larger, higher quality fruit. The same principle applies to pecan.

Research at Oklahoma State University and at Kansas State University demonstrated

the benefits of fruit thinning in pecan. Thinning fruit from overloaded Mohawk and

Shoshoni pecan trees increased nut size and percent kernel, plus improved kernel grade

(Table 1). Return bloom (flower production for next year’s crop) was increased in

Shoshoni but not Mohawk.

Fruit thinning decreases total yield per tree for the current year, but in some cases increases marketable yield. Research with the Giles cultivar indicated that yield effects are compensated by stabilizing yield from year to year (Table 2). In 1991, the yield per tree decreased as the amount of thinning increased from none to heavy. In 1992, the same trees produced a yield increase in response to shaking, leaving a similar two-year total yield from all treatments. The benefits of nut thinning are increased nut quality in terms of higher kernel percentage and kernel grade, as well as more stable yield and cash flow from year to year (Table 1).

Table 1. The influence of mechanically thinning pecan nuts on yield, kernel percentage, kernel grade, nut weight, and return bloom.

| Treatment | Nuts removed (%) | Total yield (lb/tree) | Kernel (%) | Nut size (nuts/lb) | Kernel grade (index)z | Return bloom (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mohawk (1986) | |||||||

| Unthinned | 0 | 150 | 42.1 | 93 | 2.5 | 0 | |

| Thinned | 57 | 147 | 54.2 | 68 | 1.6 | 0 | |

| Shoshoni (1986) | |||||||

| Unthinned | 0 | 171 | 46.2 | 65 | 1.2 | 14 | |

| Thinned | 55 | 90 | 52.4 | 65 | 1.2 | 58 | |

| Mohawk (1988) | |||||||

| Unthinned | 0 | 88 | 49.4 | 53 | - | 0 | |

| Thinned | 44 | 53 | 54.4 | 46 | - | 0 |

z 1=excellent quality, 2=acceptable quality, 3=reject.

Table 2. The influence of mid-summer nut thinning on yield of Giles pecan trees after four levels of shaking during July 1991 in Chetopa, KS.

| Yield (lbs/tree) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruiting shoots after shaking treatment | 1991 | 1992 | 2-year total | |

| 95 to 100% * | 68.6 | 6.7 | 75.3 | |

| 85 to 95% | 63.5 | 10.2 | 73.7 | |

| 75 to 85% | 47.4 | 21.7 | 69.1 | |

| 65 to 75% | 41 | 35.7 | 75.7 |

*control tree not shaken

Time to Thin

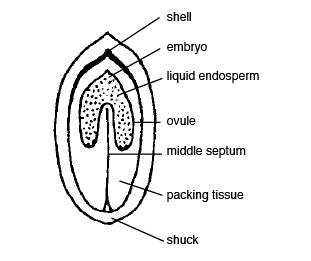

After the flower is pollinated and fertilized, the ovule (the tissue that becomes

the kernel) begins to expand and lengthen from the nut tip toward the stem. During

June and July the nut enlarges and reaches its final size as the ovule grows. As

the ovule expands, the space is filled with liquid endosperm (a watery substance)

until the ovule extends to the stem end of the nut. The nut shell begins to harden

from the tip shortly after the nut reaches full size. After 100% ovule expansion

is reached, the kernel begins to fill (kernel deposition) and nuts pass from the

water stage to the dough stage.

The process of kernel deposition requires a large amount of readily available carbohydrates.

During this process, each nut competes with other nuts for the carbohydrates manufactured

by surrounding leaves or held in the wood of supporting branches. Removing a portion

of the crop (nut thinning) before nuts begin to actively compete for a fixed amount

of carbohydrate reserve provides each remaining nut with a greater supply of carbohydrates

from which to draw. It also provides the tree with enough reserves to support a flower

crop for the following season.

Research has shown that nuts should be removed when the ovule is 50% to 100% expanded,

but before the kernel enters the dough stage. The calendar time varies with cultivar

and orchard location. Mohawk is usually ready to thin the first week of August in

Stillwater, Oklahoma and during the second week of August in Chetopa, Kansas. Thinning

the nuts earlier, while they are too small, requires force that can damage the tree.

Thinning too late, (after the nuts enter the dough stage) reduces thinning benefits

on kernel quality, return bloom, and cold hardiness.

Determination of nut development is done by cutting nuts to expose the ovule. When a nut is pulled from the tree an oval shaped scar is left on the shuck. To obtain the proper view of the ovule, the nut should be cut lengthwise at a right angle to the long axis of the oval scar. A straight cut the length of the nut will expose the expanding ovule as well as the liquid endosperm within the nut. Thinning should be done when the ovule or kernel has extended more than 50% of the distance to the stem end of the nut but before the nut reaches the dough stage (Figure 1). Cultivars with large nuts should be thinned when 50% ovule expansion has occurred. Thinning can be delayed to near 100% ovule expansion on cultivars with small nuts.

Figure 1. Longitudinal Section of a Pecan with the Ovule About 50% Expanded.

How to Thin

Nut thinning can be accomplished with a conventional tree shaker equipped with donut pads (Figure 2). Donut pads are essential in preventing injury to the tree trunk. As an additional precaution, apply a coating of grease between the rubber flap and the donut pad. This allows movement at that point and prevents movement of the bark during tree shaking.

Figure 2. A Pecan Shaker Equipped with Donut Pads.

How Much to Thin

The quantity of nuts to remove varies with many factors including nut size, cultivar characteristics, nut set, and environmental factors such as insect and disease incidence that may cause nuts to fall. To determine if a tree requires nut thinning, count 100 terminal shoots in mid-canopy and calculate the percentage of fruiting shoots. A fruiting shoot has at least one nut. After having gained extensive experience in counting fruiting shoots, you will learn to judge crop load by simple visual estimation. Optimum crop load to ensure both nut quality and return bloom is based on the nut size of the cultivar. The following guidelines have been developed:

| Nut Size | Example Cultivar | Optimum Load | |

|---|---|---|---|

| greater than 70 nuts per pound | Giles | 60 to 70% of fruiting shoots | |

| 50 to 70 nuts per pound | Wichita | 50 to 60% fruiting shoots | |

| less than 50 nuts per pound | Mohawk | 45 to 50% fruiting shoots |

As the percentage of fruiting shoots increases above the optimum nut load, nut weight,

return bloom, kernel percentage, and grade decrease.

Shaking trees to achieve the desired level of fruiting shoots is a skill developed

with experience. The duration of shaking required to remove nuts is dependent on

the equipment used, amount of fruit to be removed, tree size, and tree architecture.

Proper thinning requires good judgment by at least one keen observer on the ground.

As the tractor operator shakes the tree, the observer must watch a predetermined area

and evaluate the percentage of fruiting shoots remaining on the tree. Do not be alarmed

by the number of fruits that hit the ground. Often, heavily loaded Mohawk trees need

more than half of the crop removed to ensure quality nuts at harvest. Trees should

be shaken in 2 to 3 second spurts until thinning is complete. The distribution of

nut removal throughout the tree may be enhanced by shaking from two directions: a

north/south orientation and an east/west orientation. This compensates for branch

structure that can relay the force of shaking to various parts of the tree canopy.

Shaking orientation may vary with the type of shaker used. Growers should try variations

to determine the method that works best in each situation.

Proper management of crop load requires the grower to be thoroughly familiar with

the orchard. Not all cultivars or trees within a cultivar will require nut thinning

in a single year.

Research has shown that cultivars respond differently to shaking. Mohawk nuts dislodge

as individual nuts with only about 1% dislodging as an entire cluster. In contrast,

in Western and Maramec cultivars, over 10% of the nuts were dislodged as entire clusters

and the force required to dislodge the nuts was greater than with Mohawk. Force required

to remove nuts is not closely related to nut size. For example, relatively small

fruited cultivars such as Peruque and Giles require about the same shaking force to

remove nuts as some larger fruited cultivars. Peruque and Giles also tend to release

nuts singly rather than in clusters.

Cultivars that have shown increased profitability potential in response to fruit thinning include Mohawk, Maramec, Giles, Wichita, Cape Fear, Cheyenne, Kiowa, Barton, Graking, Peruque, and Shoshoni. Elliot and Stuart showed no positive response to fruit thinning.

Summary

Thinning the pecan nut load in heavy crop years is beneficial. It increases nut quality

as indicated by increased percentage of kernel, kernel grade, and nut weight. Increased

quality is presumably reflected in greater value. Nut thinning improves return bloom

of some cultivars, thus reducing crop variation from year to year, and has been shown

to reduce the tree’s susceptibility to cold injury. Nut thinning can be accomplished

with a conventional pecan shaker equipped with donut pads.

In order to make informed management decisions, the grower must be familiar with the concept and the technique. We encourage growers to test nut thinning in a portion of their orchards and personally evaluate the results.

Becky Carroll

Extension Horticulturist

Pecans and Tree Fruit