Management of Soybean Inoculum

Introduction

Soybeans are legumes, which means they have the ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen (N) through a symbiotic relationship with the soil bacteria Bradyrhizobium japonicum (Kirchner, Buchanan). This relationship is critical because overall soybean nitrogen demand is high, with most reports indicating that soybeans need 4.5 to 5.0 pounds of nitrogen per bushel of crop yield. This means that a 30-bushel crop requires between 135 and 150 pounds of nitrogen per acre (in comparison, corn and wheat need only 1.0 or 2.0 pounds, respectively). Reports on the amount of nitrogen that can be fixed through the symbiotic relationship between the soybean plant and bacteria vary widely. Some reports indicate that as much as 90% of the total needed N can be fixed, while others suggest as low as 50%. Much of the difference in demand is likely to depend on total nitrogen need, based on overall yield potential.

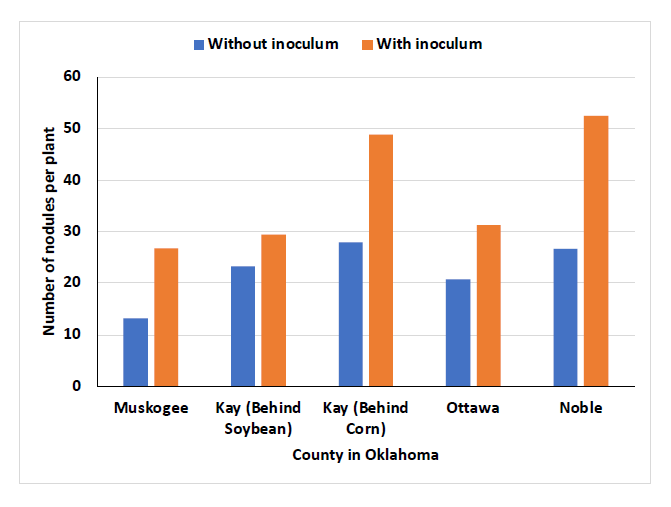

To ensure the N-fixing relationship between the soybean plant and bacteria is formed, it is often advisable for growers to treat soybean seeds with inoculum prior to planting. This places a high concentration of bacteria in close proximity to the seed and emerging root, facilitating the quick formation of the relationship. As many species of rhizobium will survive in a feld where soybeans are frequently grown, there has always been a question about how consistently inoculum should be applied to soybean seeds in Oklahoma. This is especially true when costs are high and commodity prices are declining. In a recent evaluation of several soybean-producing regions, most soybean plants grown in soil collected from Oklahoma felds did have greater nodulation with the addition of appropriate inoculum (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The number of nodules on inoculated and non-inoculated soybean roots. These were collected at peak flowering (R2 growth stage), which is often when nodulation is peaked. Soybean plants were grown in soils collected from fields across Oklahoma (counties identified on x-axis).

Impact of Environmental Conditions on Inoculum Management:

The bacteria associated with soybean inoculum are living organisms. Therefore, conditions prior to application to the seed and after being applied to the seed, including both prior to and following planting, can significantly impact their ability to form a successful relationship with the soybean plant.

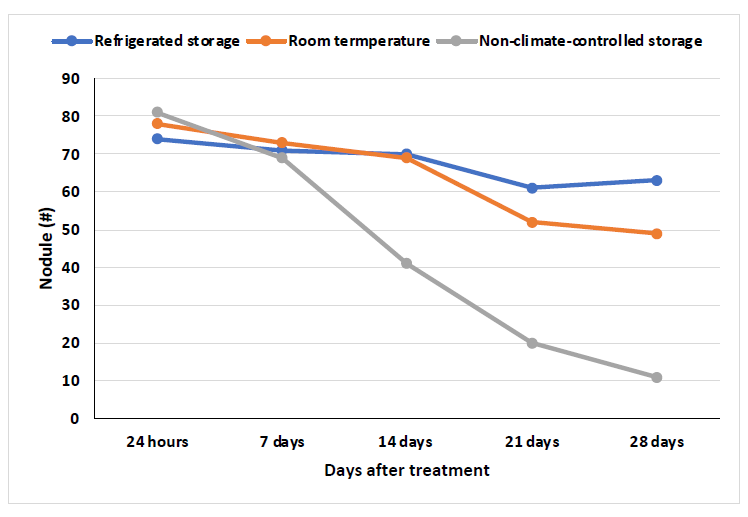

It is always recommended that inoculum be stored in a cool, dark environment prior to being applied to the seed. These conditions help preserve the long-term viability of these bacteria outside of a host relationship. An evaluation of soybean inoculant viability after being short-term in different conditions found that viability can decrease when kept in non-climate-controlled conditions in as little as 14 days (Figure 2). Furthermore, viability decreased at 21 days when stored at room temperature com-pared to refrigerated storage.

Figure 2. The number of nodules formed on a soybean plant when inoculated with materials that had been stored in a non-climate-controlled environment (shed), room temperature (AC ofce), and a refrigerated environment (cold room) for 24 hours through 28 days.

Generally, it is best not to store inoculum in the freezer, as it forms ice crystals within the living cells, damaging the cell membranes and decreasing the likelihood of viability upon thawing. However, from an application standpoint, a new product should be purchased if additional storage is required beyond the current growing season.

Another frequent question is, “How often should I inoculate my soybean?” It is currently recommended that growers apply inoculum to seed with rhizobium every time soybean is planted in crop rotations, primarily due to the challenging conditions of-ten faced in Oklahoma systems. The species and strains of bacteria used to inoculate soybean crops are not native to Oklahoma’s soil. As a result, they are not well adapted to our environment. In addition to needing to outcompete native microbial populations in the soil, periods of hot and dry conditions, common to Oklahoma agroecosystems, appear to reduce the bacteria’s ability to survive without a host in the soil.

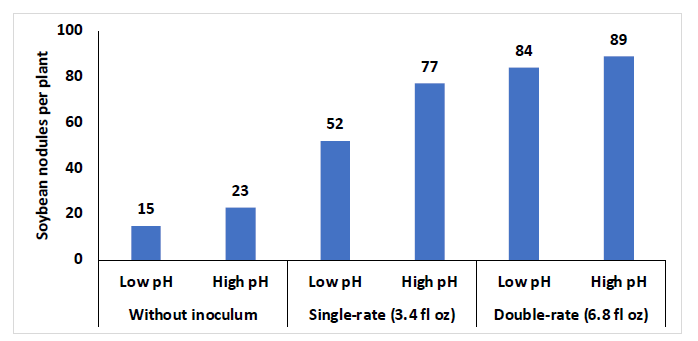

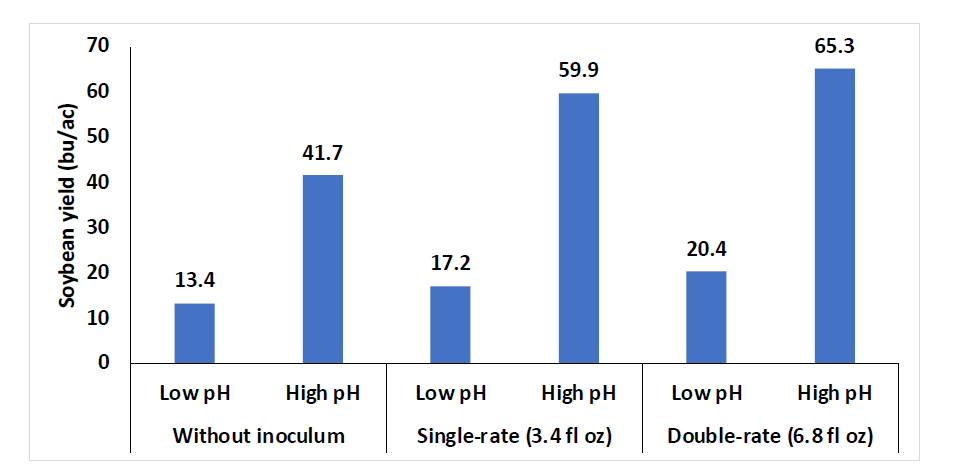

Soil pH also influences the relationship between soybeans and N-fixing bacteria. These bacteria optimally function at a pH range that closely resembles that of most crop plants. Lowering the soil pH below a critical threshold, specifically to a pH of less than 5.5, reduces the viability of the bacteria, hampers N-fixation processes and diminishes the capacity of both the bacteria and soybean plants to form this symbiotic relationship. While applying inoculum to soybean seeds (Figure 3) can help, it often doesn’t lead to increased yields when the pH is too low. Therefore, inoculation is most effective when soil pH is first corrected through liming.

Figure 3. Impact of soil pH and inoculation on soybean nodule formation. Nodules were measured on soybean that were grown in a greenhouse with soils that were collected on local pH plots that ranged from a soil pH of 4.0 to 8.0. Inoculum was applied as Exceed liquid inoculum. Single applications were 3.4 fluid ounces per 100 pounds of seed at a rate of 5×109 CFU/mL. Low pH rep-resents soil that had a measured pH of 5.5 or below. Higher soil pH represents soils with a pH above 5.5 but not higher than 7.0.

Figure 4. Impact of soil pH and inoculation on soybean yield. These soybeans are grown in a greenhouse with soils collected on local pH plots that ranged from a soil pH of 4.0 to 8.0. Inoculum was applied as Exceed liquid inoculum. Single applications were 3.4 fluid ounces per 100 pounds of seed at the rate of 5x109 CFU/mL. Low pH represents soil that had a measured pH of 5.5 or below. Higher soil pH represents soils with a pH above 5.5 but not higher than 7.0.

Conclusion

The symbiotic relationship between the soybean plant and the rhizobium bacteria is critical for optimal production in Oklahoma. While in another soybean-producing state, this relationship can occur naturally in the soil system. Due to the unfavorable conditions often experienced in Oklahoma systems, this relationship has to be managed through the application of inoculum on the soybean seed.

It is essential to understand that, unlike other seed treatments, inoculum is a living organism and must be treated as such. This includes maintaining the material in a climate-controlled environment, especially one that moderates temperature. The longer the material is to be stored, the cooler the environment needs to be to maintain viability. Long-term (beyond the current year) should be maintained in more specialized facilities. Additionally, like all living organisms in the soil, these bacteria have an optimal and suboptimal soil pH that favors growth and productivity. Maintaining an optimum pH is not only critical for the soybean plant but also for the viability of the bacteria in the soil. If low pH does exist, growers should manage the pH initially and then consider management of soybean inoculum.