Compressed Air Systems – Waste Reduction

American industry spends $4.5 billion annually on compressed air energy (DOE, 2004). Compressed air is one of the most expensive sources of energy used in a food plant with an overall operating efficiency of between 10 and 15 percent (DOE, 2000). This means the cost of compressed air is about eight times more expensive than electricity. Most food plants use compressed air for a variety of functions, including cylinder activation, cleanup operations, hoists, agitator drives, pump drives, enclosure cooling, dewatering and de-ionizing. In many food plants the cost of compressed air is not documented, leaving compressed air systems prime candidates for waste and abuse. The purpose of this fact sheet is to help identify and reduce waste in compressed air systems used in food manufacturing facilities.

Examples of compressed air waste include leaks, dirty filters, inappropriate uses of compressed air, system over-pressurization, mismanaged compressors and excessive system pressure losses. Reducing the cost of compressed air decreases the operating cost of a food plant facility, which adds profit directly to the bottom line.

Five Steps to Reduce Waste

Reducing compressed air system waste can add profit to your operation. The five steps to reduce waste in compressed air systems are:

Analyze your compressed air system.

Identify current (and future) use of compressed air, including periodic loads.

Understand compressed air supply system and controls.

Diagram compressed air system, including piping.

Identify system deficiencies.

Evaluate actions to correct deficiencies.

Implement the best actions.

Track results.

1. Analyze Your Compressed Air System

Identify current (and future) use of compressed air, including periodic loads. Examine all uses of compressed air in the plant by enlisting the help of engineers, technicians and line personnel. Do not forget to ask the cleanup crew about compressed air usage.

Record all use points, volumes and required pressures using known values or best estimates. Ensure the supply of the existing compressed air system matches the demand.

Understand your compressed air supply system and controls. Visit with your engineer, technician or supplier to determine how your compressors operate and how they are controlled. Find out how much it costs to operate and maintain your system per year based on actual expenses or estimates of expense.

Diagram your compressed air system, including piping. Everyone will be able to view and discuss the system using diagrams, which will help streamline the identification and correction of deficiencies.

2. Identify System Deficiencies

Conduct a self-audit of your plant compressed air system or hire an auditor. According to Plant Services magazine (Merritt, 2005), the 10 most typical targets of a compressed air audit should be:

Leaks

Over-pressurization

Matched supply and demand

Inappropriate use of piping tees

Improperly sized piping

Flow restrictions

Inadequate air storage

Inappropriate use of compressed air

Opportunities to use electrical drives instead of air

Maintenance of filters and separators

3. Evaluate Actions to Correct Deficiencies

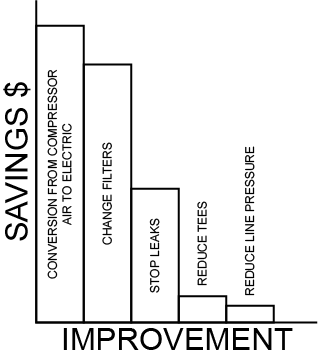

Pick the “low hanging” fruit first. Correct the deficiencies that are costing the most, but are the least expensive to repair. A Pareto diagram (a type of bar graph) can be useful in this case to help separate the “critical few” deficiencies from the “trivial many” possibilities that exist. An example Pareto diagram is shown in Figure 1, where the source of the remedy for the problem is listed on the x-axis. The y-axis shows the estimated savings (less the cost of implementation) that would result from removing the deficiency. The projects with the tallest bars on the Pareto chart should be selected for implementation.

Figure 1. Pareto diagram used to help select the most effective action(s) (categories are examples only).

4. Implement the best actions

This step requires action to be taken to implement the best alternative(s) identified in step three. Some processors postpone action because of time constraints. It may be worthwhile to hire extra help to implement actions immediately. Each action should be verifiable in terms of results (e.g. increased capacity, reduced power consumption, reduction of downtime or quality improvement). Actions also should be measurable in terms of cost savings.

5. Track results

All actions taken should be reviewed periodically to ensure that results are as expected, or to determine if something has changed that requires additional attention or action. When changes have occurred, the five-step process can be reiterated to solve new problems. The process of making incremental changes for the best is called “continuous improvement.”

Food Safety

Compressed air often is not considered a concern for food safety and quality, but it can be a significant source of contamination. Compressed air may carry oils and particles that are classified as food adulterants. In addition, compressed air systems may serve as a breeding ground for microbes. When air is used to dust off food contact surfaces, or is exhausted in areas above exposed product, the potential for contamination exists. Filters that are capable of removing oil and bacteria should be installed near the point of use. Compressed air systems should be included in existing sanitation programs and inspected on a regular basis (e.g. quarterly) for cleanliness and cleaned when necessary.

Equipment

Ultrasonic leak detectors are very useful for detecting leaks in compressed air and vacuum systems. This technology is especially valuable in noisy plant environments where leaks may not be heard. A detector can cost thousands of dollars and will detect leaks within 50 feet. If at all possible, try one or more units before making a purchasing decision, or ask an experienced user. The units shown in Figures 2 through 4 are for example only, and their use in this publication is not an endorsement of the manufacturer, supplier or the performance of the equipment.

Figure 2. Inficino “Whisper” ultrasonic leak detector, about $270 at www.reliabilitydirect.com.

Figure 3. VPE Ultrasonic leak detector, about $900 at www.monarchinstrument.com.

Figure 4. Robinair 16455 Ultrasonic leak detector, about $300 at www.valuetesters.com.

Resources for Further Study

The Compressed Air Challenge (CAC) is an independent, non-profit organization whose mission is “…to enhance industrial competitiveness through improved energy efficiency.” A visit to its Web site, www.compressedairchallenge.org, will uncover many resources and suggestions for reducing the cost of your compressed air system. Many products are available for free or for a nominal charge. The CAC even offers workshops to help train your personnel to manage and maintain compressed air systems.

In a case study report available as a free download from the CAC Web site, candy manufacturer H.B. Reese Company was able to take two compressors totaling 150 horsepower offline by increasing output and product quality. They also shaved 4 percent from their annual energy costs, reduced maintenance costs and increased production by 15 percent without bringing additional compressors online.

A useful list of online resources is available at the Flex Your Power Web site, www.flexyourpower.org. Flex Your Power is California’s energy efficiency marketing and outreach campaign. To view its list of resources, go to the toolbar on the home page and choose “Best Practices Guides” from the “Industrial” drop-down menu. Then, choose the link for “Food Growers and Beverage Processors Best Practice Guide.”

Conclusion

Compressed air systems in food processing operations are often overlooked as a source of waste. Many systems are inefficient and pose potential food safety and quality hazards. A wide variety of resources, tools and techniques are available to help diagnose and improve your plant air system. Identifying and repairing problems in compressed air systems can be a rewarding experience that results in increased income and improved food quality. As energy prices continue to increase rapidly, the efficiency of compressed air systems is even more important.

References

Studebaker, Paul. 2006. Stop the bleeding. Plant Services Vol 27, No. 6. pgs 33-40. Putnam Media, Inc. Itasca, IL.

DOE, 2004. Assessment of the market for compressed air efficiency services. U.S. Department of Energy.

DOE, 2000. Determine the cost of compressed air for your plant. U.S. Department of Energy, Compressed air tip sheet #1, Document number 102000-0986.

Merritt, 2005. On the Hunt, the top 10 targets of a compressed air audit. Plant Services, Vol. 26, No. 5, pgs 29-36. Putnam Media, Inc., Itasca, IL.

Timothy J. Bowser

FAPC Food Process Engineer