Calving Time Management for Beef Cows and Heifers

- Jump To:

- Recognize Normal Calving

- The Three Stages of Parturition

- Dystocia

- Prepare Before Helping

- Signs of Impending Calving in Cows or Heifers

- When and How to Examine the Cow

- Proper Placement of Obstetrical Chains

- Forced Extraction of the Calf

- Anterior Presentation

- Posterior Presentation

- Other Ideas on Pulling Calves

- Abnormal Presentations

- Rotating the Calf at Parturition to Aid in Delivery

- Prolapses

- Summary

- References

Calf losses at calving time are often a result of dystocia (difficult calving) problems. Many of these losses occur to calves born to first calf heifers and can be prevented if the heifers and cows are watched closely and the dystocia problems detected and corrected early. A veterinarian should handle serious and complicated calving problems. Ranchers must use good judgment in their decisions as to which problems will require professional help, and the earlier help is sought the greater the survival rate of both cow and calf.

Recognize Normal Calving

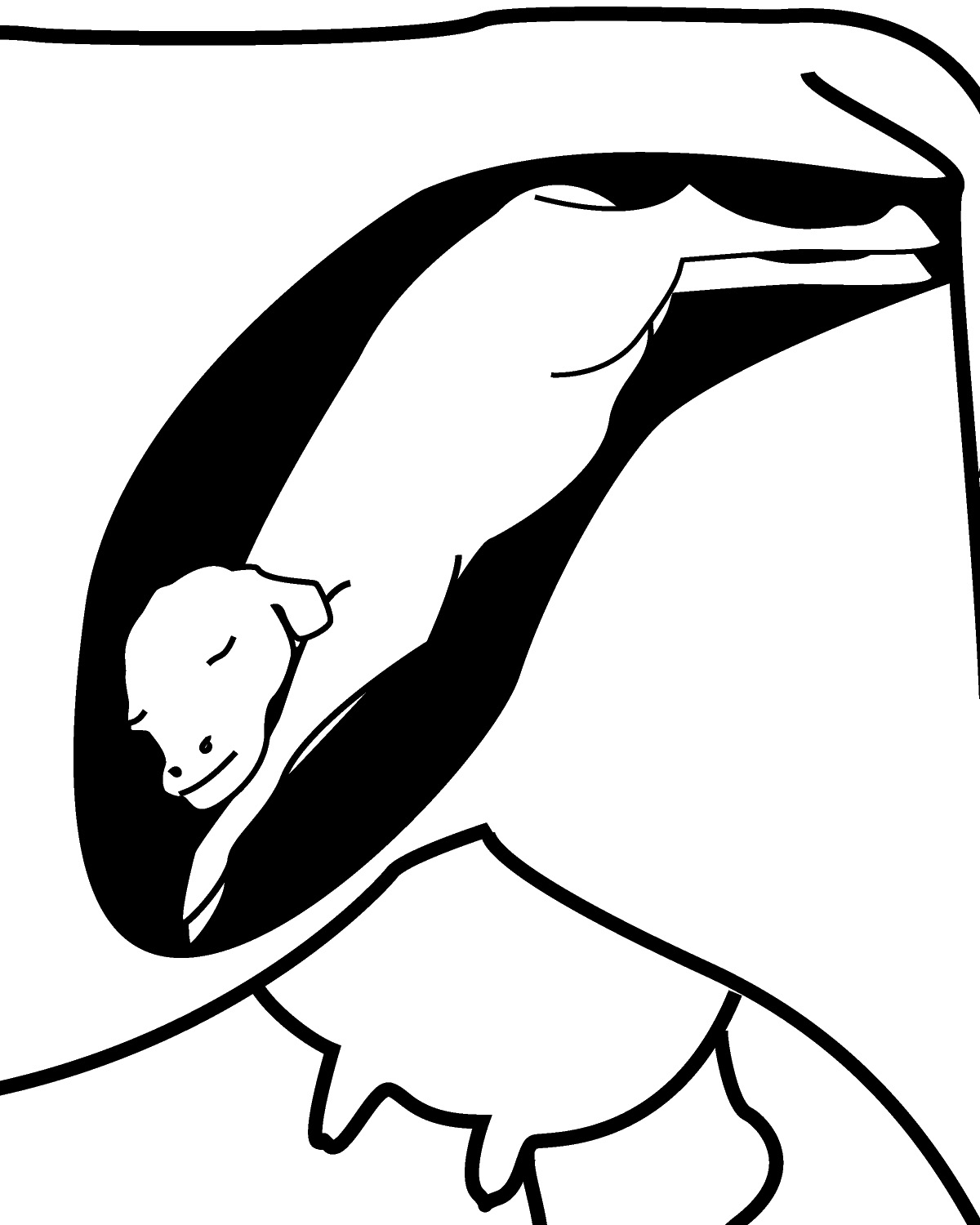

If the calf is normally presented (Figure 1) and the pelvic area is large enough, the vast majority of animals will give birth without assistance. Recognizing a normal calving is just as important as knowing when a calving is abnormal. This way you will not give help when it is not needed.

Figure 1. An anterior presentation

The Three Stages of Parturition

Stage 1

The first stage of parturition is dilation of the cervix. The normal cervix is tightly closed right up until the cervical plug is completely dissolved. In stage 1, cervical dilation begins some four to 24 hours before the actual birth. During this time the progesterone block is no longer present and the uterine muscles are becoming more sensitive to all factors that increase the rate and strength of contractions. At the beginning, the contractile forces primarily influence the relaxation of the cervix but uterine muscular activity is still rather quiet. Stage 1 is likely to go completely unnoticed, but there may be some behavioral differences such as isolation or discomfort. Near the end of stage 1 ranchers may observe elevation of the tail, switching of the tail, and increased mucous discharge.

Stage 2

The second stage of parturition is defined as the delivery of the newborn. It begins with the entrance of the membranes and fetus into the pelvic canal and ends with the completed birth of the calf. The second stage is the one producers are really interested in because this is where all the action is. Clinically the onset of stage 2 is marked by the appearance of membranes or water bag at the vulva. The traditional texts, fact sheets, magazines, and other publications state that stage 2 in cattle lasts from two to four hours. Data from Oklahoma State University and the USDA experiment station at Miles City, Montana, would indicate that stage 2 is much shorter being approximately one hour for heifers and one-half hour for adult cows. See When and How to Examine a Cow on page 3. In heifers, not only is the pelvic opening smaller, but also the soft tissue has never been expanded. Older cows have had deliveries before and birth should go quite rapidly unless there is some abnormality such as a very large calf, backwards calf, leg back, or twins.

Stage 3

The third stage of parturition is the shedding of the placenta or fetal membranes. In cattle this normally occurs in less than eight to 12 hours. The membranes are considered retained if after 12 hours they have not been shed. Years ago it was considered necessary to remove the membranes by manually unbuttoning the attachments. Research has shown that manual removal is detrimental to uterine health and future conception rates. Administration of antibiotics usually will guard against infection and the placenta will slough in four to seven days. Contact your veterinarian for the proper management of retained placenta.

Dystocia

What is dystocia or a difficult birth? Traditionally, it is any birth that has needed assistance. According to that definition, any unassisted birth was a normal birth, but by the definition an unassisted birth could still result in weak or dead calf at birth. A more modern definition of dystocia would be a birth that needs assistance or results in a weakened or dead calf or injury to the dam.

Causes of Dystocia

What are the causes of dystocia? Most common is relative fetal oversize, which could be defined as a calf too big, pelvis too small, or both. As for calving difficulty, prevention is worth a pound of cure. Proper sire selection is a key to preventing calving difficulty. Underdeveloped heifers and heifers bred to bulls with large birth weights are both factors that cause increased incidence of difficult births. The second most prevalent cause is abnormal presentation or position. The normal presentation in cattle is anterior presentation or head first and the normal position would be right side up with head and fore limbs extended into the pelvic canal. Any position that involves the calf’s head turned back or one of the legs turned back is abnormal. Remember a normal delivery cannot be achieved unless the head and both front limbs are presented into the pelvic canal and on through the vulva. A third cause of dystocia would be lack of uterine contractions or uterine fatigue. The causes of this are complex and not completely understood. Sometimes hormonal imbalances may result in the cervix not being completely dilated or uterine contractions not occurring frequently or strongly enough. Low calcium levels such as seen with milk fever or grass tetany may be responsible. In any case those problems usually require the assistance of a veterinarian to correct. Other causes of dystocia are twins or genetic mistakes (fetal monsters).

Effects of Dystocia on the Calf

What are the effects of dystocia or difficult birth on the calf? Obvious to everyone is a dead calf at birth or one killed during the assistance process. Additional effects include trauma such as leg fractures, ruptured diaphragm, and nerve damage due to excessive pulling, improper placement of chains, or the development of a hiplock. A third and greatly overlooked effect is a weak calf, sometimes called weak calf syndrome, which may be brought on by a prolonged stage 2. This is due to increased time exposed to increased pressure associated with increased uterine contractions and straining of the dam.

A prolonged stage 2 with no progress in delivery of the calf is going to result in decreased oxygen and increased carbon dioxide to the fetus. Such calves do not have normal respiratory efforts. They do not have strong gasping and panting efforts. They do not have rapid respiration or heart rates necessary to distribute oxygen to the tissues and carbon dioxide back to the lungs. Lactic acid and carbon dioxide levels remain quite high. These calves are depressed, they do not sit up well, they do not shake their heads and ears, and if weather is cold they do not shiver to warm themselves. Shivering increases metabolism, which increases heat. These calves have poor metabolism to begin with and their body temperature consequently drops. Even those that first appeared to breath and sit up normally soon become depressed, are slow to rise, and are slow to nurse. Many do not nurse without assistance and die within 12 to 24 hours. Even those that do nurse, may nurse too late for good antibody absorption. In summary, the effect of dystocia is not just dead calves and injured heifers, but also weak and sick calves.

Effects of Dystocia on Post-calving Fertility

In addition to being the greatest cause of baby calf mortality, calving difficulty markedly reduces reproductive performance during the next breeding season.

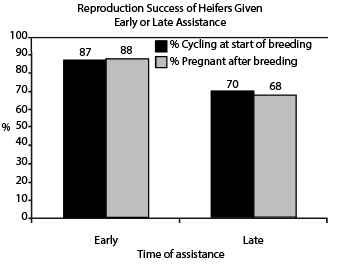

Results from a Montana study (Doornbos, et al., 1984) showed that heifers receiving assistance in early stage 2 of parturition returned to heat earlier in the post-calving period and had higher pregnancy rates than heifers receiving traditionally accepted obstetric assistance (Figure 2). In this study heifers were either assisted when the fetal membranes (water bag) appeared (Early) or were allowed to progress normally and assisted only if calving was not completed within two hours of the appearance of the water bag (Late).

Heifers that were allowed to endure a prolonged labor had a 17% lower rate of cycling at the start of the next breeding season. In addition, the rebreeding percentage was 20% lower than the counterparts that were given assistance in the first hour of labor.

Prolonged deliveries of baby calves (in excess of one to one and a half hours) often result in weakened calves and reduced rebreeding performance in young cows.

Figure 2. Impact of early or late assistance in subsequent rebreeding performance of first calf heifers. Doornbos, et al. 1984.

Prepare Before Helping

- Equipment: Before calving season starts do a walk through of pens, chutes, and calving stalls. Make sure that all are clean, dry, strong, safe, and functioning correctly. This is a lot easier to do on a sunny afternoon than on a cold dark night when you need them.

- Protocol: Before calving season starts develop a plan of what to do, when to do it, who to call for help (along with phone numbers), and how to know when you need help. Make sure all family members or helpers are familiar with the plan. It may help to write it out and post copies in convenient places. Talk to the local veterinarian about the protocol and incorporate his/her suggestions. Your veterinarian will be a lot more helpful when you have an emergency during the kids’ school program if you have talked a few times during regular hours.

- Lubrication: Many lubricants have been used and one of the best lubricants is probably the simplest – non-detergent soap and warm water.

- Supplies: The stockman should always have in his medicine chest the following: disposable obstetrical sleeves, non-irritant antiseptic, lubricant, obstetrical chains (60 inch and/or two 30 inch chains), two obstetrical handles, mechanical calf pullers, and injectable antibiotics. Do not forget the simple things like a good flashlight with extra batteries and some old towels or a roll of paper towels. It may be helpful for you to have all these things and other items you may want to include packed into a 5 gallon bucket to make up an obstetrical kit so you can grab everything at once.

Signs of Impending Calving in Cows or Heifers

As the calving season approaches, the cows will show typical signs that will indicate parturition is imminent. Changes that are gradually seen are udder development or making bag and the relaxation and swelling of the vulva or springing. These indicate the cow is due to calve in the near future. There is much difference between individuals in the development of these signs and certainly age is a factor. The first calf heifer, particularly in the milking breeds, develops udder for a very long time, sometimes for two or three months before parturition. The springing can be highly variable too. Most people notice that Brahman influence cattle seem to spring much more than does a Holstein.

Typically, in the immediate two weeks preceding calving, springing becomes more evident, the udder is filling, and one of the things that might be seen is the loss of the cervical plug. This is a very thick tenacious, mucous material hanging from the vulva. It may be seen pooling behind the cow when she is lying down. Some people mistakenly think this happens immediately before calving, but in fact this can be seen weeks before parturition and therefore is only another sign that the calving season is here.

The immediate signs that usually occur within 24 hours of calving would be relaxation of the pelvic ligaments and strutting of the teats. These can be fairly dependable for the owner that watches his cows several times a day during the calving season. The casual observer or even the veterinarian who is knowledgeable of the signs but sees the herd infrequently cannot accurately predict calving time from these signs. The relaxation of the pelvic ligaments really cannot be observed in fat cows (body condition score 7 or greater). However, relaxations of the ligaments can be seen very clearly in thin or moderate body condition cows and can be a sign of impending parturition within the next 12 to 24 hours. These changes are signs the producer or herdsman can use to more closely pinpoint calving time. Strutting of the teats is not really very dependable. Some heavy milking cows will have strutting of the teats as much as two or three days before calving and on the other hand, a thin poor milking cow may calve without strutting of the teats.

Another thing that might be seen in the immediate 12 hours before calving would be variable behavior such as a cow that does not come up to eat or a cow that isolates herself into a particular corner of the pasture. However, most of them have few behavioral changes until the parturition process starts.

When and How to Examine the Cow

It is important to know with complete confidence exactly when and how long to leave the cow and when to seek help. An issue facing the rancher at calving time is the amount of time heifers or cows are allowed to be in labor before assistance is given. Traditional textbooks, fact sheets, and magazine articles state that stage 2 of labor lasted from two to four hours. Stage 2 is defined as that portion of the birthing process from the first appearance of the water bag until the baby calf is delivered. Data from Oklahoma State University and the USDA experiment station at Miles City, Montana, clearly show that stage 2 is much shorter, lasting approximately 60 minutes in first calf heifers and 30 minutes in mature cows (Table 1).

In these studies, heifers that were in stage 2 labor much more than one hour or cows that were in stage 2 much more than 30 minutes definitely needed assistance. Research information also shows that calves from prolonged deliveries are weaker and more disease prone, even if born alive. In addition, cows or heifers with prolonged deliveries return to heat later and are less likely to be bred for the next calf crop. Consequently a good rule of thumb: If the heifer is not making significant progress one hour after the water bag or feet appear, examine the heifer to see if you can provide assistance. Mature cows should be watched for only 30 minutes before a vaginal examine is conducted. If you cannot safely deliver the calf yourself at this time, call your local veterinarian immediately.

Most ranches develop heifers fully and use calving ease bulls to prevent calving difficulties. However, a few difficult births are going to occur each calving season. Using the concept of evening feeding to get more heifers calving in daylight and giving assistance early will save a few more calves. This results in healthier more productive two-year cows to rebreed next year.

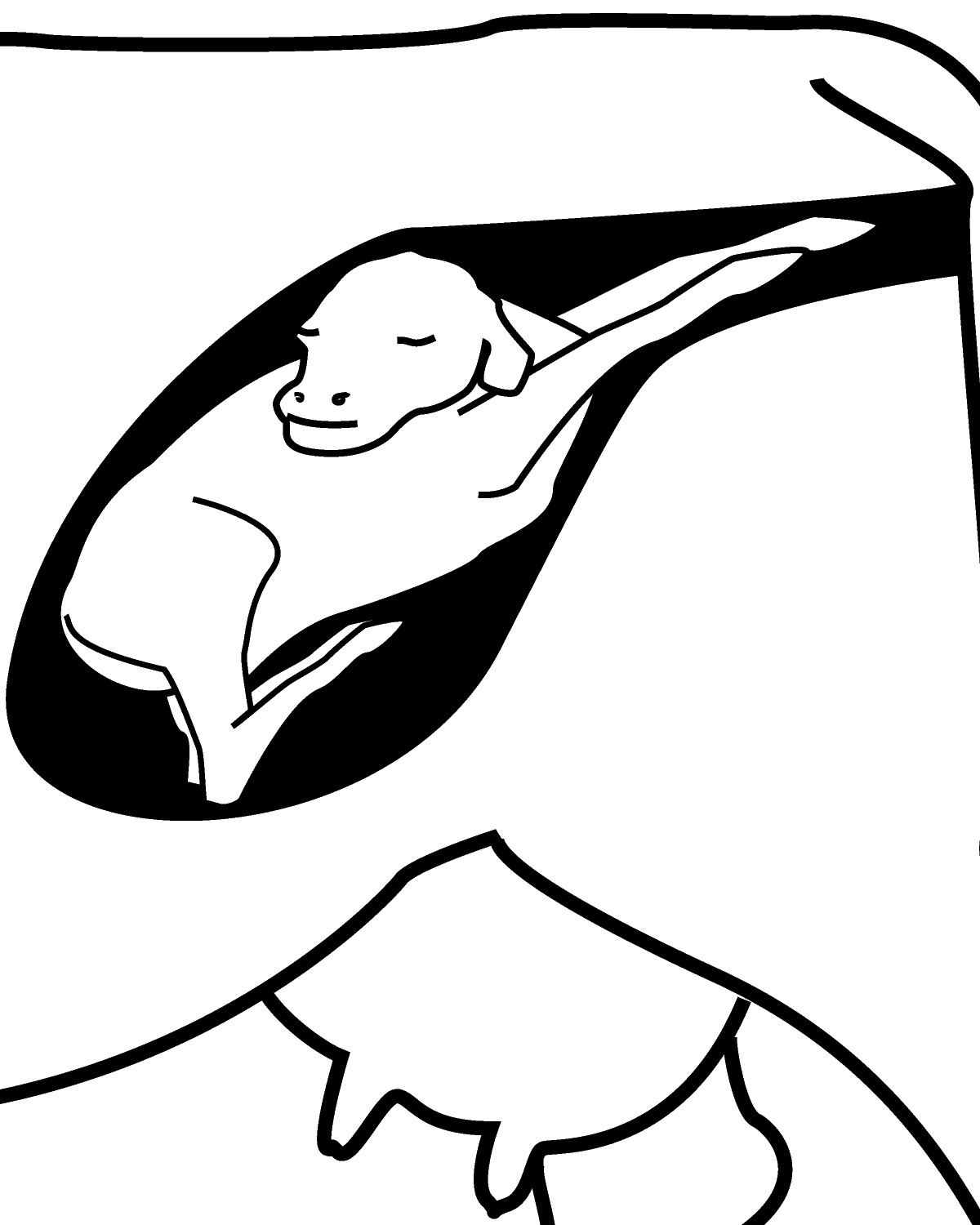

If nothing is showing after a period of intensive straining of second-stage labor – a period of approximately 30 minutes in a cow and 60 minutes in a heifer – then examine her to determine if presentation is normal. Wash the vulva, anus, and the area in between using soap and warm water. Using a disposable sleeve (shoulder length) and a good lubricant (usually available from your veterinarian), insert your hand slowly and do not rupture the waterbag. If the calf’s presentation is not an anterior (Figure 1) or posterior position (Figure 3) or if the calf is very large or the heifer small, you may want to seek professional help.

Table 1. – Research results for length of stage 2 parturition.

| Study | No. of animals | Length of stage 2 |

|---|---|---|

| USDA (Montana)* | 31 mature cows | 22.5 minutes |

| USDA (Montana)* | 29 first calf heifers | 54.1 minutes |

| Oklahoma State University** | 35 first calf heifers | 55.0 minutes |

*Doornbos, et al. 1984. JAS: 59:1

**Putnam, et al. 1985. Therio: 24:385

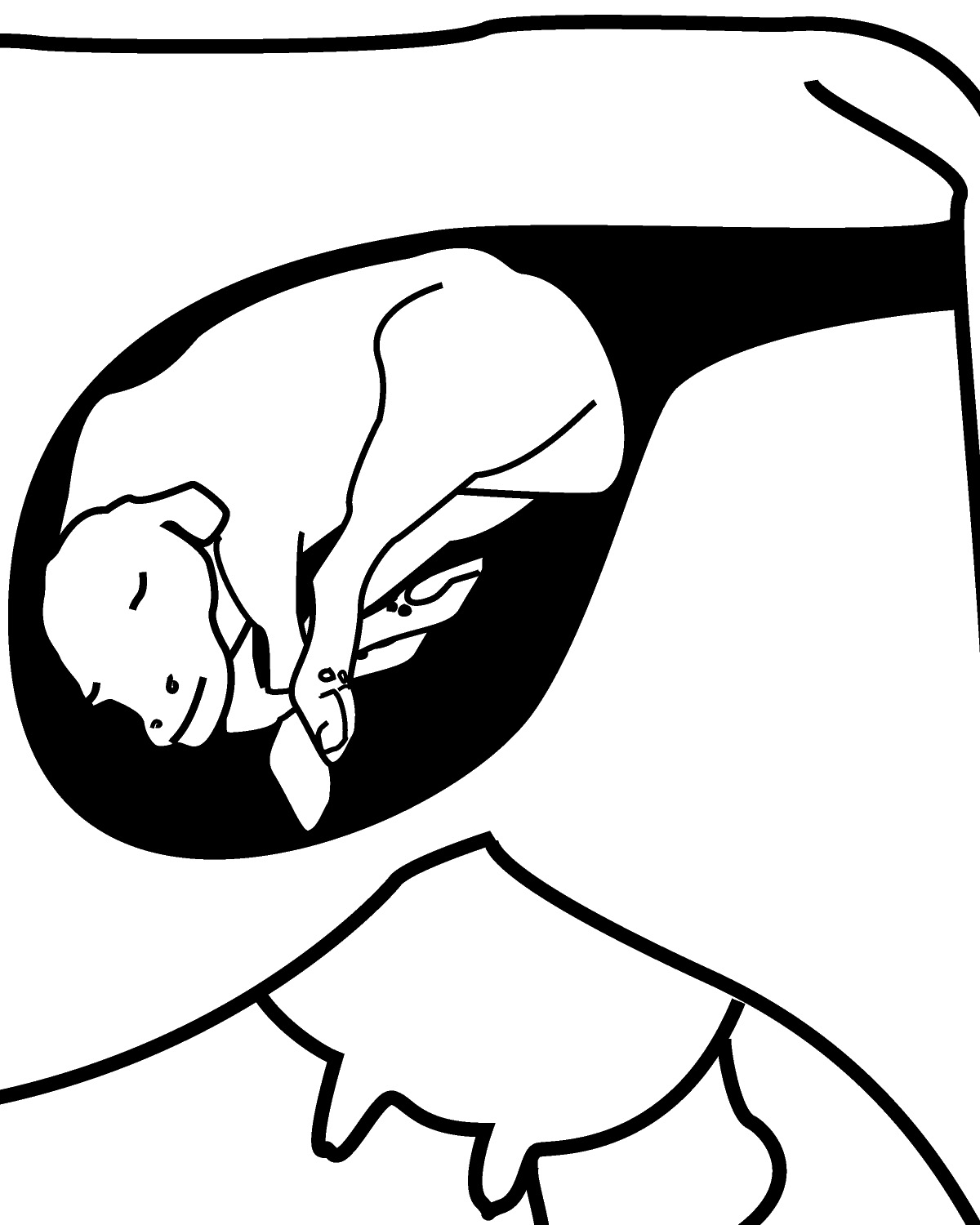

Proper Placement of Obstetrical Chains

To properly use obstetrical chains when assisting with a difficult birth, follow the example in Figure 4. To attach the chain, loop it around the thin part of the leg above the fetlock. Then, make a half hitch and tighten it below the joint and above the foot. Make certain that the chain is positioned in such a manner that it goes over the top of the toes. In this way the pressure is applied so as to pull the sharp points of the calf’s hooves away from the soft tissue of the vaginal wall.

Forced Extraction of the Calf

It is very important at all times to exert pressure only when the animal strains and to relax completely when the patient relaxes. The old idea of maintaining a steady pressure during assistance is wrong, unless the cow has already given up and no assistance is coming from her.

Excessive or improper pressure often causes injuries to the dam such as vaginal tears, uterine rupture, paralysis, or uterine prolapse. All can usually be prevented but when they occur they need the immediate attention of your veterinarian.

Vaginal tears generally heal with proper antibiotic therapy. Uterine rupture usually results in death. Some animals will recover from calving paralysis but may require prolonged care and may not breed again.

Pulling on a calf should only be done when the presentation and posture of the calf are normal. This applies both to an anterior position (Figure 1) and a posterior position (Figure 3). Excess force should never be used in pulling a calf. In most cases, no more than two men should be allowed to pull and then only when the cow strains. Lubricant and patience will often solve the tightest case. Use extreme caution if a mechanical puller is being used.

Figure 3. A posterior presentation

Figure 4. Place loop above and halfhitch below fetlock joint. Connecting chain should be on the top of the leg.

The first step is to examine the cow to check calf position and determine if assistance is necessary. It is generally easier to correct any abnormal presentation if the cow is standing. If a cow or heifer will not get up, she should be so placed that she is not lying directly on the part of the calf which has to be adjusted. Thus, if the calf’s head is turned back toward the cow’s right flank, the cow should be made to lie on her left flank so that the calf’s head is uppermost. This provides more room in the uterus for manipulation.

Once the calf is in a correct anterior or posterior position, delivery will be easier if the cow is lying down. When the calf’s limbs are located, find out whether they are forelimbs or hindlimbs. To do this start by feeling the fetlock and moving the hand up the limb. In the hindlimb the next joint is the hock with the prominent point. In the forelimb there is also a prominent point, the point of the elbow, but before this is reached one can feel the knee joint, which is flat and has no prominences.

The calf may be alive or dead. Sometimes movements can be detected in a live calf by placing the fingers in the mouth, seizing the tongue, or touching the eyelids.

If the genital passage of the cow is dry or if the calf itself is dry, plenty of lubricant should be used. Attempts to repel (push back) the calf should be made between labor pains. Similarly, attempts to deliver the calf by traction will be a lot easier if they are made to coincide with the contractions of the cow.

Anterior Presentation

An anterior presentation is forefeet first, head resting on the limbs, and the eyes level with the knees (Figure 1). As stated above, in this presentation the cow does not usually require assistance, unless it is a heifer at first calving, the calf is dead, or the calf is too big for the cow.

If the calf is dead, tie a chain around the head behind the ears and pass it through the mouth. This will prevent the head from twisting when the limbs are being pulled. With a live calf you can do this by placing a hand on the head and ensuring that the head is kept straight. Traction should not be exerted simultaneously on the head and limbs until the head enters the pelvis. A large calf, with shoulders too wide for the pelvis, is sometimes held up at this stage. If so, pull one limb only so that the elbow and shoulder of one limb only enter the pelvis. Then, while the pull on the limb is continued, the other limb is treated in the same way until both feet project equally from the genital passage. Now apply traction on both limbs and on the head until the head protrudes from the vulva, and from this stage the principle traction is exerted on the limbs again.

It can be seen that traction on both limbs at the same time will result in both shoulders entering the pelvis at once. If the shoulders of a wide-chested calf can be made to enter on a slant and can be pulled through in that position, delivery will be made easier.

IMPORTANT: Traction on the calf in the early stages should be exerted upward (in the direction of the tailhead) and not downward. Once the calf is in the pelvic cavity, traction should be straight backward and then downward. The calf thus passes through the birth canal in the form of an arc.

If the passage of the hind end of the calf presents any difficulty, the body of the calf should be grasped and twisted to an angle of about 45 degrees. Delivery is then made with the calf half-turned on its side. This allows for easier passage of a calf with well-developed stifle joints.

Sometimes a calf gets stuck at the hips (hiplock). Do not just pull, rotate the calf as described above or try turning the cow onto her back, then over onto the side opposite to the one you found her on and try some gentle assistance.

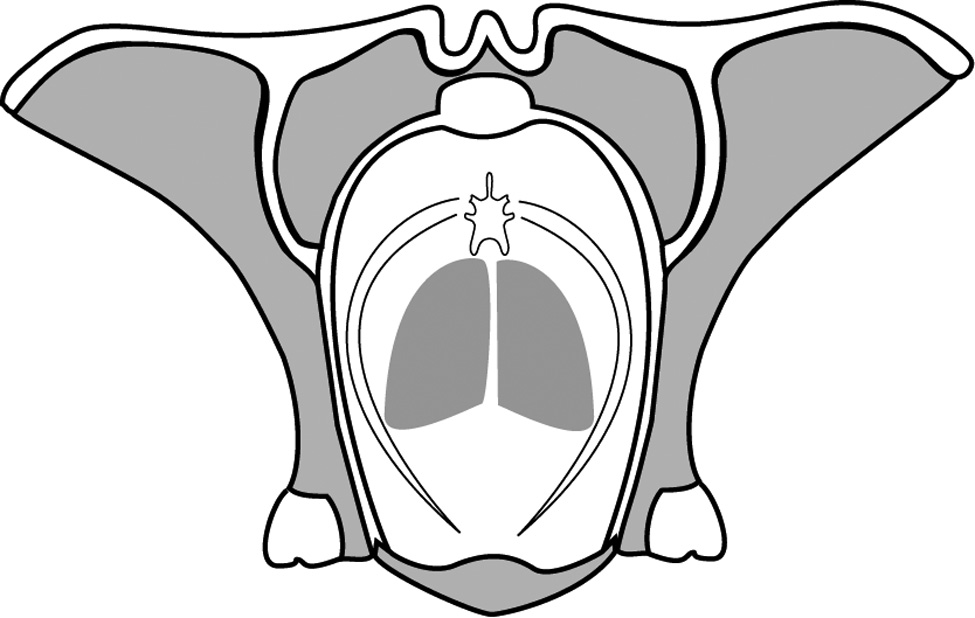

Posterior Presentation

In a posterior presentation, both the hindfeet are presented with the calf’s spine upward toward the cow’s spine (Figure 3), and the sole or bottom of the hooves will face upward. In a normal anterior presentation (head and forelimbs first) the hooves are downward. If the calf is on its back, however, the position of the hooves is reversed in each of these presentations.

In the posterior presentation, the head is the last part to be expelled, and there is a risk of suffocation or brain damage due to lack of oxygen. Delivery should be as quickly as possible by traction on the hind legs. Traction should be exerted on one limb until the corresponding stifle joint has been drawn over the pelvic brim. It may be necessary to push the other limb partly back into the uterus at the same time. In this way the two stifle joints will enter separately into the pelvis and assist easier delivery.

After the first limb has been drawn back sufficiently, traction should be applied to both limbs simultaneously. If this does not succeed, cross one limb over the other and pull on the lower limb. This will make the calf rotate slightly to one side and delivery will proceed more smoothly.

The calf’s tail may have a tendency to protrude upward and damage the top of the vagina. Be sure the tail is down between the legs by placing your hand on the tailhead while the calf is entering the pelvic cavity.

After delivery of posterior presentation, more careful attention should be given to removal of mucus from the mouth and nose because of a greater danger of suffocation than in an anterior presentation. A stiff straw should be used to briskly tickle the nostril of the newborn. This will stimulate the calf to snort, sneeze or cough and inhale air into the lungs to begin breathing as soon as possible.

Other Ideas on Pulling Calves

The chain should be tightly fastened above the fetlocks with a half-hitch below the fetlock before applying traction in anterior or posterior presentations. If it becomes necessary to pull on the jaw or head, try to do it by hand or use a soft cotton or nylon rope being careful not to apply excessive pull so as not to fracture the jaw or damage the spinal cord. If a rope is used apply the rope behind the poll and through the mouth. Protect the birth canal from laceration by the sharp teeth by guiding the head with your hand. After the head and neck have passed through the cervix, traction should be applied to the legs only.

Traction should be applied in a steady, even manner. Jerky, irregular pulls are painful and dangerous. Only pull when the cow is straining. If you are pulling and a sudden obstruction occurs, stop and examine the birth canal and calf to find out what is wrong before proceeding. To avoid lacerations to the soft birth canal, time should be allowed for enlargement of the birth canal as the calf advances.

Abnormal Presentations

The following figures illustrate presentation of the calf other than anterior or posterior presentations.

Two Front Legs Presented: Head Retained

If the head cannot be felt, do not assume the calf is coming backward. The two front legs may be presented and the head retained (Figure 5). Before pulling on the limbs, distinguish between forelimbs and hindlimbs as described earlier. Where the head is bent back into the right flank of the cow it will be easier to correct if the left hand is used and vice versa. By grasping the muzzle, the ear, or the lower jaw; or by placing the thumb and middle finger in the eye sockets, the head can be raised and directed into the pelvis. Do not pull hard on the jaw because the jaw can be easily broken.

Figure 5. Two front legs presented with head back

In all these cases, the head can be brought up and straightened more easily if the body of the calf is at the same time pushed farther back in the uterus. This can be done by placing the hand between the front legs and pushing back the chest, the head being pulled at the same time with aid of a chain placed on the lower jaw. Try to carry out all these operations when the cow is not straining vigorously.

Head Between Forelegs

Sometimes the head falls well down between the legs (Figure 6). Replace one or both limbs into the uterus to raise the head by one of the methods described above.

Another method is to turn the cow on her back. The head of the calf will fall toward

the cow’s spine and then can be more easily guided into the pelvis by a hand alone

or else by a loop around the lower jaw.

Figure 6. Two front legs presented with head back between legs

Head Out: One or Both Forelegs Retained

The calf may have the head out, but one or both forelegs retained (Figure 7). Secure the head by placing a chain or rope behind the poll and through the mouth then lubricate the head and push it back into the uterus. Then search for the limbs one at a time. Each limb should be grasped just above the fetlock and bent at the knee. Now push the bent knee toward the spinal column and push back so as to bend all the joints of the limb. Meanwhile the hand is gradually moved down the limb toward the fetlock. Now raise the fetlock over the pelvic brim and the leg can move forward.

If the hand alone does not work, chain the fetlock. Push the knee at the same time and pull the rope. Cover the hoof to avoid damage.

Figure 7. Calf presented with its head in the birth canal but one or both forelegs retained.

Breech Presentation

Figure 8 shows a breech presentation. The calf has to be repelled well back into the uterus. Then grasp a leg below the stifle and work a hand down to the foot. Place the hoof into the palm of your hand, withdrawing you arm until the foot is drawn over the pelvic brim. This manipulation is made easier by rotating the hock outward as the foot is pulled up and back.

Figure 8. Calf presented in breech position.

Twins

If twins enter the vagina one at a time, there is no problem. However, occasionally twins are presented together and block the birth canal. In most of these cases one comes head first and the other tail first (Figure 9). Extract the closest twin. If in doubt, first extract the twin presenting hindlegs after first repelling the other twin far into the uterus.

Before this, make sure both limbs belong to the same calf. To do this, feel along each limb to where it joins the body and feel along the body to the opposite limb. Rope each limb separately and identify the ropes for each twin. If one or both twins are abnormally presented, correct as in a single birth before attempting delivery.

Figure 9. Twin calves entering the birth canal.

Rotating the Calf at Parturition to Aid in Delivery

Pulling on a calf should only be done when the presentation and posture of the calf are correct. This applies to both the anterior (forward) position (Figure 1) and the posterior (backward) position (Figure 3). A large calf, with shoulders too wide for the pelvis, is sometimes held up at this stage (Figure 10). If so, pull one limb only so that the elbow and shoulder of one limb only enter the pelvis. Then, while the pull on the limb is continued, the other limb is treated in the same way until both feet project equally from the genital passage. Now apply traction on both limbs and on the head until the head protrudes from the vulva, and from this stage the principle traction is exerted on the limbs again. It can be seen that traction on both limbs at the same time will result in both shoulders entering the pelvis at once.

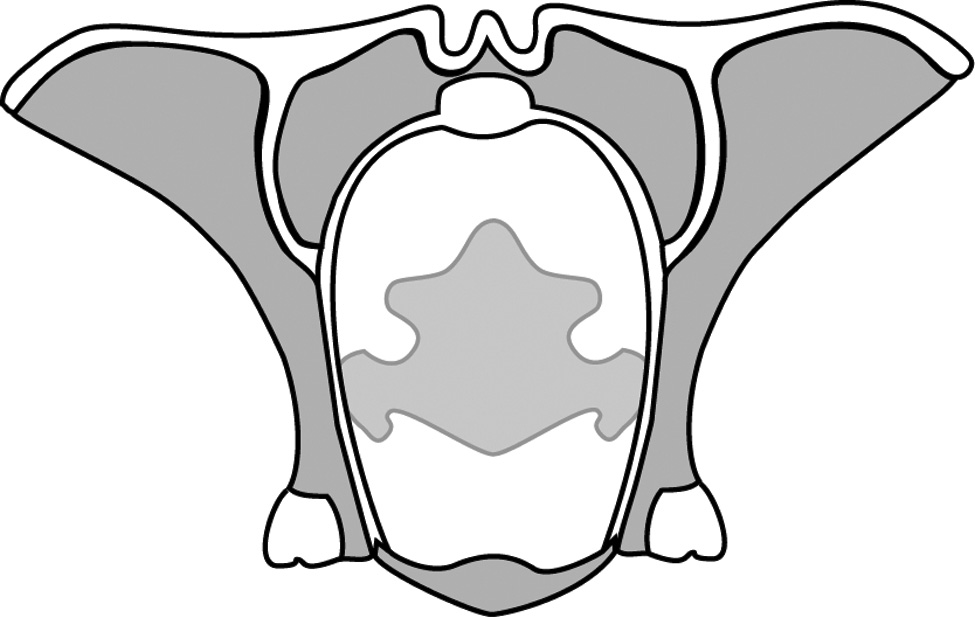

Figure 10. The shoulders or hips of a large calf may be wider than the horizontal axis of the pelvic opening.

The pelvis has an oval shaped opening with the largest dimension being the vertical axis, and the smaller dimension is the horizontal width. If the shoulders of a large birth weight calf can be made to enter on a slant and can be pulled through in that position, delivery will be made easier. Apply traction that will allow the calf to be turned about 90 degrees so that the widest part of the shoulders will match the largest dimension of the pelvic opening (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Rotation of the calf to match the widest dimensions of calf and pelvic opening.

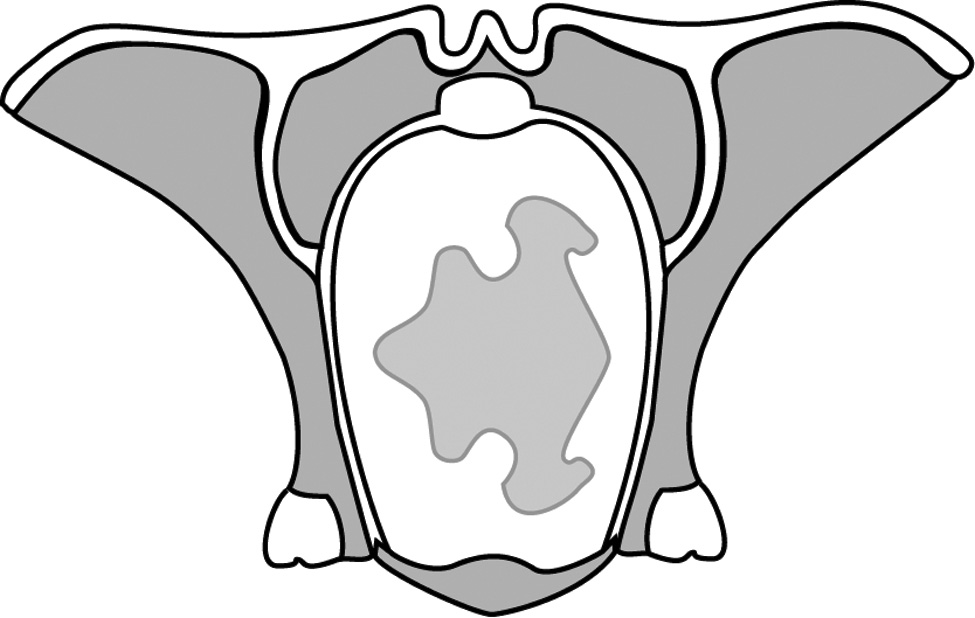

After the shoulders have passed the pelvic opening, the calf can be returned to the normal upright position because the torso is larger in the vertical dimension (Figure 12).;

Figure 12. Rotating the calf back to the upright position to match the depth of the thoracic cavit with the depth of the pelvic opening.

Hiplock is the next likely obstruction that is met when pulling a calf. If the passage of the hind end of the calf presents any difficulty, the body of the calf should be grasped and twisted to an angle of about 45 degrees. Delivery is then made with the calf half-turned on its side. This allows for easier passage of a calf with well-developed stifle joints.

Prolapses

Prolapses occur occasionally in beef cows. Most prolapses occur very near the time of calving. Two distinct kinds of prolapse exist.

Uterine prolapse requires immediate attention and if treated soon, most animals have an uneventful recovery. If they subsequently rebreed and become pregnant there is no reason to cull animals suffering uterine prolapse after calving. Uterine prolapse is not likely to reoccur. Some may suffer uterine damage or infection that prevents conception and should therefore be culled. If the uterus becomes badly traumatized before treating, the animal dies from shock or hemorrhage.

Vaginal prolapse, however, that which occurs before calving is a heritable trait and is likely to reoccur each year during late pregnancy. Such animals should not be kept in the herd. The condition will eventually result in the loss of cow, calf, or both plus her female offspring would be predisposed to vaginal prolapse.

Research (Patterson, et al, 1981) from the USDA station at Miles City, Montana, reported that 153 calvings of 13,296 calvings from a 14-year span were associated with prolapse of the reproductive tract. Of those 153 prolapses, 124 (81%) were vaginal prolapses and 29 (19%) were uterine prolapses. The subsequent pregnancy rate following prolapse among first calf heifers was 28% and the pregnancy rate among adult cows following a prolapse was only 57.9%.

Table 2. Gestation table (based on 283 days)

| Breeding Date | Due Date | Breeding Date | Due Date | Breeding Date | Due Date | Breeding Date | Due Date | Breeding Date | Due Date | Breeding Date | Due Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan 1 | Oct 10 | March 3 | Dec 10 | May 3 | Feb 9 | July 3 | April 11 | Sept 2 | June 11 | Nov 2 | Aug 11 |

| Jan 2 | Oct 11 | March 4 | Dec 11 | May 4 | Feb 10 | July 4 | April 12 | Sept 3 | June 12 | Nov 3 | Aug 12 |

| Jan 3 | Oct 12 | March 5 | Dec 12 | May 5 | Feb 11 | July 5 | April 13 | Sept 4 | June 13 | Nov 4 | Aug 13 |

| Jan 4 | Oct 13 | March 6 | Dec 13 | May 6 | Feb 12 | July 6 | April 14 | Sept 5 | June 14 | Nov 5 | Aug 14 |

| Jan 5 | Oct 14 | March 7 | Dec 14 | May 7 | Feb 13 | July 7 | April 15 | Sept 6 | June 15 | Nov 6 | Aug 15 |

| Jan 6 | Oct 15 | March 8 | Dec 15 | May 8 | Feb 14 | July 8 | April 16 | Sept 7 | June 16 | Nov 7 | Aug 16 |

| Jan 7 | Oct 16 | March 9 | Dec 16 | May 9 | Feb 15 | July 9 | April 17 | Sept 8 | June 17 | Nov 8 | Aug 17 |

| Jan 8 | Oct 17 | March 10 | Dec 17 | May 10 | Feb 16 | July 10 | April 18 | Sept 9 | June 18 | Nov 9 | Aug 18 |

| Jan 9 | Oct 18 | March 11 | Dec 18 | May 11 | Feb 17 | July 11 | April 19 | Sept 10 | June 19 | Nov 10 | Aug 19 |

| Jan 10 | Oct 19 | March 12 | Dec 19 | May 12 | Feb 18 | July 12 | April 20 | Sept 11 | June 20 | Nov 11 | Aug 20 |

| Jan 11 | Oct 20 | March 13 | Dec 20 | May 13 | Feb 19 | July 13 | April 21 | Sept 12 | June 21 | Nov 12 | Aug 21 |

| Jan 12 | Oct 21 | March 14 | Dec 21 | May 14 | Feb 20 | July 14 | April 22 | Sept 13 | June 22 | Nov 13 | Aug 22 |

| Jan 13 | Oct 22 | March 15 | Dec 22 | May 15 | Feb 21 | July 15 | April 23 | Sept 14 | June 23 | Nov 14 | Aug 23 |

| Jan 14 | Oct 23 | March 16 | Dec 23 | May 16 | Feb 22 | July 16 | April 24 | Sept 15 | June 24 | Nov 15 | Aug 24 |

| Jan 15 | Oct 24 | March 17 | Dec 24 | May 17 | Feb 23 | July 17 | April 25 | Sept 16 | June 25 | Nov 16 | Aug 25 |

| Jan 16 D | Oct 25 | March 18 | Dec 25 | May 18 | Feb 24 | July 18 | April 26 | Sept 17 | June 26 | Nov 17 | Aug 26 |

| Jan 17 | Oct 26 | March 19 | Dec 26 | May 19 | Feb 25 | July 19 | April 27 | Sept 18 | June 27 | Nov 18 | Aug 27 |

| Jan 18 | Oct 27 | March 20 | Dec 27 | May 20 | Feb 26 | July 20 | April 28 | Sept 19 | June 28 | Nov 19 | Aug 28 |

| Jan 19 | Oct 28 | March 21 | Dec 28 | May 21 | Feb 27 | July 21 | April 29 | Sept 20 | June 29 | Nov 20 | Aug 29 |

| Jan 20 | Oct 29 | March 22 | Dec 29 | May 22 | Feb 28 | July 22 | April 30 | Sept 21 | June 30 | Nov 21 | Aug 30 |

| Jan 21 | Oct 30 | March 23 | Dec 30 | May 23 | March 1 | July 23 | May 1 | Sept 22 | July 1 | Nov 22 | Aug 31 |

| Jan 22 | Oct 31 | March 24 | Dec 31 | May 24 | March 2 | July 24 | May 2 | Sept 23 | July 2 | Nov 23 | Sept 1 |

| Jan 23 | Nov 1 | March 25 | Jan 1 | May 25 | March 3 | July 25 | May 3 | Sept 24 | July 3 | Nov 24 | Sept 2 |

| Jan 24 | Nov 2 | March 26 | Jan 2 | May 26 | March 4 | July 26 | May 4 | Sept 25 | July 4 | Nov 25 | Sept 3 |

| Jan 25 | Nov 3 | March 27 | Jan 3 | May 27 | March 5 | July 27 | May 5 | Sept 26 | July 5 | Nov 26 | Sept 4 |

| Jan 26 | Nov 4 | March 28 | Jan 4 | May 28 | March 6 | July 28 | May 6 | Sept 27 | July 6 | Nov 27 | Sept 5 |

| Jan 27 | Nov 5 | March 29 | Jan 5 | May 29 | March 7 | July 29 | May 7 | Sept 28 | July 7 | Nov 28 | Sept 6 |

| Jan 28 | Nov 6 | March 30 | Jan 6 | May 30 | March 8 | July 30 | May 8 | Sept 29 | July 8 | Nov 29 | Sept 7 |

| Jan 29 | Nov 7 | March 31 | Jan 7 | May 31 | March 9 | July 31 | May 9 | Sept 30 | July 9 | Nov 30 | Sept 8 |

| Jan 30 | Nov 8 | April 1 | Jan 8 | June 1 | March 10 | Aug 1 | May 10 | Oct 1 | July 10 | Dec 1 | Sept 9 |

| Jan 31 | Nov 9 | April 2 | Jan 9 | June 2 | March 11 | Aug 2 | May 11 | Oct 2 | July 11 | Dec 2 | Sept 10 |

| Feb 1 | Nov 10 | April 3 | Jan 10 | June 3 | March 12 | Aug 3 | May 12 | Oct 3 | July 12 | Dec 3 | Sept 11 |

| Feb 2 | Nov 11 | April 4 | Jan 11 | June 4 | March 13 | Aug 4 | May 13 | Oct 4 | July 13 | Dec 4 | Sept 12 |

| Feb 3 | Nov 12 | April 5 | Jan 12 | June 5 | March 14 | Aug 5 | May 14 | Oct 5 | July 14 | Dec 5 | Sept 13 |

| Feb 4 | Nov 13 | April 6 | Jan 13 | June 6 | March 15 | Aug 6 | May 15 | Oct 6 | July 15 | Dec 6 | Sept 14 |

| Feb 5 | Nov 14 | April 7 | Jan 14 | June 7 | March 16 | Aug 7 | May 16 | Oct 7 | July 16 | Dec 7 | Sept 15 |

| Feb 6 | Nov 15 | April 8 | Jan 15 | June 8 | March 17 | Aug 8 | May 17 | Oct 8 | July 17 | Dec 8 | Sept 16 |

| Feb 7 | Nov 16 | April 9 | Jan 16 | June 9 | March 18 | Aug 9 | May 18 | Oct 9 | July 18 | Dec 9 | Sept 17 |

| Feb 8 | Nov 17 | April 10 | Jan 17 | June 10 | March 19 | Aug 10 | May 19 | Oct 10 | July 19 | Dec 10 | Sept 18 |

| Feb 9 | Nov 18 | April 11 | Jan 18 | June 11 | March 20 | Aug 11 | May 20 | Oct 11 | July 20 | Dec 11 | Sept 19 |

| Feb 10 | Nov 19 | April 12 | Jan 19 | June 12 | March 21 | Aug 12 | May 21 | Oct 12 | July 21 | Dec 12 | Sept 20 |

| Feb 11 | Nov 20 | April 13 | Jan 20 | June 13 | March 22 | Aug 13 | May 22 | Oct 13 | July 22 | Dec 13 | Sept 21 |

| Feb 12 | Nov 21 | April 14 | Jan 21 | June 14 | March 23 | Aug 14 | May 23 | Oct 14 | July 23 | Dec 14 | Sept 22 |

| Feb 13 | Nov 22 | April 15 | Jan 22 | June 15 | March 24 | Aug 15 | May 24 | Oct 15 | July 24 | Dec 15 | Sept 23 |

| Feb 14 | Nov 23 | April 16 | Jan 23 | June 16 | March 25 | Aug 16 | May 25 | Oct 16 | July 25 | Dec 16 | Sept 24 |

| Feb 15 | Nov 24 | April 17 | Jan 24 | June 17 | March 26 | Aug 17 | Nay 26 | Oct 17 | July 26 | Dec 17 | Sept 25 |

| Feb 16 | Nov 25 | April 18 | Jan 25 | June 18 | March 27 | Aug 18 | May 27 | Oct 18 | July 27 | Dec 18 | Sept 26 |

| Feb 17 | Nov 26 | April 19 | Jan 26 | June 19 | March 28 | Aug 19 | May 28 | Oct 19 | July 28 | Dec 19 | Sept 27 |

| Feb 18 | Nov 27 | April 20 | Jan 27 | June 20 | March 29 | Aug 20 | May 29 | Oct 20 | July 29 | Dec 20 | Sept 28 |

| Feb 19 | Nov 28 | April 21 | Jan 28 | June 21 | March 30 | Aug 21 | May 30 | Oct 21 | July 30 | Dec 21 | Sept 29 |

| Feb 20 | Nov 29 | April 22 | Jan 29 | June 22 | March 31 | Aug 22 | May 31 | Oct 22 | July 31 | Dec 22 | Sept 30 |

| Feb 21 | Nov 30 | April 23 | Jan 30 | June 23 | April 1 | Aug 23 | June 1 | Oct 23 | Aug 1 | Dec 23 | Oct 1 |

| Feb 22 | Dec 1 | April 24 | Jan 31 | June 24 | April 2 | Aug 24 | June 2 | Oct 24 | Aug 2 | Dec 24 | Oct 2 |

| Feb 23 | Dec 2 | April 25 | Feb 1 | June 25 | April 3 | Aug 25 | June 3 | Oct 25 | Aug 3 | Dec 25 | Oct3 |

| Feb 24 | Dec 3 | April 26 | Feb 2 | June 26 | April 4 | Aug 26 | June 4 | Oct 26 | Aug 4 | Dec 26 | Oct 4 |

| Feb 25 | Dec 4 | April 27 | Feb 3 | June 27 | April 5 | Aug 27 | June 5 | Oct 27 | Aug 5 | Dec 27 | Oct 5 |

| Feb 26 | Dec 5 | April 28 | Feb 4 | June 28 | April 6 | Aug 28 | June 6 | Oct 28 | Aug 6 | Dec 28 | Oct 6 |

| Feb 27 | Dec 6 | April 29 | Feb 5 | June 29 | April 7 | Aug 29 | June 7 | Oct 29 | Aug 7 | Dec 29 | Oct 7 |

| Feb 28 | Dec 7 | April 30 | Feb 6 | June 30 | April 8 | Aug 30 | June 8 | Oct 30 | Aug 8 | Dec 30 | Oct 8 |

| March 1 | Dec 8 | May 1 | Feb 7 | July 1 | April 9 | Aug 31 | June 9 | Oct 31 | Aug 9 | Dec 31 | Oct 9 |

| March 2 | Dec 9 | May 2 | Feb 8 | July 2 | April 10 | Sept 1 | June 10 | Nov 1 | Aug10 |

Summary

Many calving difficulties could be eliminated by proper development of replacement heifers and/or breeding first calf heifers to bulls that will sire calves with below average birth weights. Of most importance is to know when to help, when to quit, and when it is time to call the veterinarian. Remember the length of stage 2 of parturition is important to calf survival and if a problem cannot be corrected within 20 to 30 minutes, you should seek assistance. To learn more about how to assist cows or heifers at calving, check out two videotapes available from your local OSU Extension Office. These two videos are called VT-323 Calving Management-Parturition and VT-324 Calving Management-Dystocia. In the second video (VT-324), Dr. Larry Rice, Professor-Emeritus, demonstrates how to check for cervical dilation.

References

Doornbos, D.E., R.A. Bellows, P.J. Burfening and B.W. Knapp. 1984. Effects of dam age, prepartum nutrition, and duration of labor on productivity and postpartum reproduction in beef females. Journal of Animal Science. Vol. 59: pp 1-10.

Patterson, D.J., R.A. Bellows, and P.J. Burfening. 1981. Effects of caesarean section, retained placenta, and vaginal or uterine prolapse on subsequent fertility in beef cattle. Journal of Animal Science. Vol. 53: pp 916.

Putnam, M.R., L.E. Rice, R.P. Wettemann, K.S. Lusby, and B. Pratt. 1985. Clenbuterol (PlanipartTM) for the postponement of parturition in cattle. Theriogenology. Vol 24. No. 4. pp 385-393.

Glenn Selk

Professor Emeritus