Body Condition of Horses

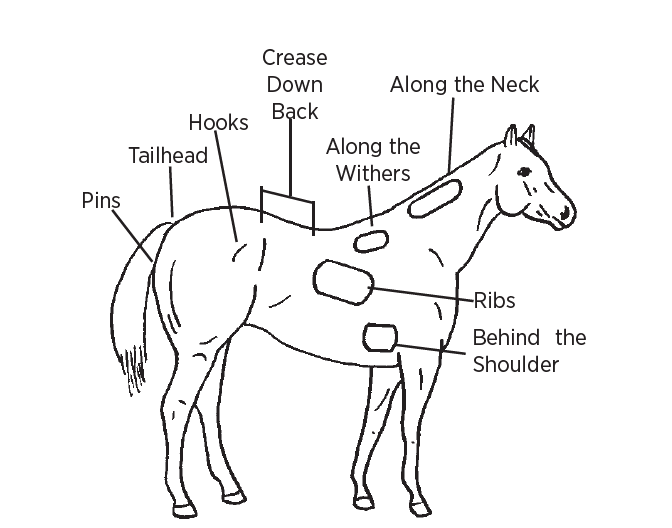

Body condition refers to the amount of fat on a horse’s body. Fat is tissue that serves to store energy and is produced when the horse is digesting more energy than is needed for maintenance and production processes. Over time, horses consuming rations with more energy than is needed will increase body fat. Horses receiving less energy per day than is needed will use stored body fat for an energy source, which then decreases the amount of body condition. Much of this body fat is subcutaneous, meaning fat accumulates in layers immediately below the horse’s skin. This fat cover can be visibly assessed in several specific locations on the horse’s body (Figure 1). The desired level of body condition will vary between horses. As a rule, horses used in athletic performance will maintain a lower body condition than non-performing horses. Additionally, horses will vary in the optimal body condition for productive functions because of individual differences. For example, one horse may perform athletic competition more effectively in a thinner condition as compared with another individual performing the same task in a heavier body condition.

The ability to accurately assess body condition allows horse owners to make ration

adjustments that maintain horses at desired fat levels. A universally used scoring

system assists communication between horse owners. Moreover, it aids in the application

of recommendations to maintain desired levels of body condition for production and

management. For more information on how to correctly score your horse’s body condition

over time, visit the OSU Extension Online Course Catalog.

Using Body Condition Scores to Quantify Body Condition

The most tested and universal scoring system for assessing body condition was developed by researchers at Texas A&M University in the early 1980s using quarter horse broodmares. Since that time, nutritionists, breeding and farm managers, trainers of performance horses, veterinarians, those involved with evaluating animal welfare, and other equine professionals have incorporated the scoring system into their practice.

This scoring system places the body condition of horses on a scale of 1 to 9, and

provides descriptions, which are used to assess fat accumulation along the neck, withers,

over the ribs, behind the shoulder, around the tailhead and the crease on the back.

While the scoring system can be used on all horses, it was initially developed to

quantify the influence of body condition on the reproductive performance of mares.

Body Condition and Reproductive Performance in Broodmares

Extensive research and field trials document that reproductive efficiency of mares is affected by body condition.

- Non-bred mares managed in a body condition of 4 or less will delay the time of their first ovulation of the breeding season. This delay can be three to four weeks as compared with mares in a body condition of 5 or greater, which is significant when breeding managers intend to settle open mares in the early part of the breeding season.

- Once cycling, mares in a condition of 4 or less can be expected to require more cycles per conception. Research on one group of mares resulted in thin mares requiring an average of three cycles before settling as compared with one and one-half cycles per conception for similarly managed mares with condition scores of 5 or higher. More cycles per conception results in increased costs for the breeding manager and mare owner.

- Pregnancy rates are also affected. Mares in body conditions of 4 or less have overall pregnancy rate reductions as large as 20% less than mares in a greater body condition. Moreover, early pregnancy losses are significantly greater in mares with body scores of 4 or less.

To summarize, mares in body conditions of 4 or less will be poor breeders and more susceptible to pregnancy losses than mares maintained at higher body condition scores. Frequently, the onset of cold weather, changes in housing, transportation, foaling and lactation reduce body condition. As such, recommendations are for mares to enter the foaling and breeding season in body condition scores of 6 or 7.

One concern expressed by owners is that mares with a body condition greater than 5 or 6 will have more trouble foaling. These concerns are unwarranted, as significant research has shown body conditions of 7 or greater have no effect on gestation length, length of the foaling process, size of foal or placenta, or measures of foal viability. However, there is no benefit to maintaining a broodmare in an obese condition.

Obesity

It is worth noting that obesity in horses, or those over a BCS of 7 are as worthy of consideration as horses that are considered too thin (BCS <3). Obese horses are at increased risk of insulin dysregulation, equine metabolic syndrome and laminitis. Over 40%- 50% of horses may be considered obese worldwide, representing a significant issue with equine well-being. It has also repeatedly been documented that owners routinely underestimate the body condition score of their horse.

Owners should also be aware that if implementing a weight loss program, little change in BCS may occur even with losses of body weight. These may be explained by changes in fat deposits that are not subcutaneous (such as visceral body fat) and thus, do not affect body condition.

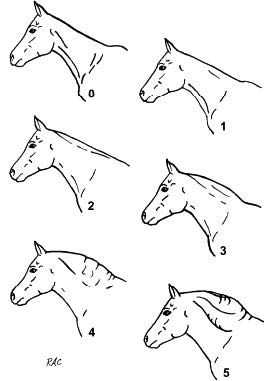

Cresty Neck Scores

The cresty neck score has been suggested to assist in identifying which horses and ponies are at a higher risk of obesity related metabolic disorders. Scored zero through 5, ponies with a cresty neck score greater than 3 have 18.9 times greater risk of hyperinsulinemia (carter et al). Therefore owners are encouraged to use both scoring systems, especially in ponies.

Body Condition Scoring System

- Poor. Animal is extremely emaciated. Spinous processes (portion of the vertebrae of the backbone, which project upward), ribs, tailhead and bony protrusions of the pelvic girdle (hooks and pins) are prominent. Bone structure of withers, shoulders and neck are easily noticeable. No fatty tissues can be felt.

- Very Thin. Animal is emaciated. Slight fat covering over base of the spinous processes. Transverse processes (portion of vertebrae, which project outward) of lumbar (loin area) vertebrae feel rounded. Spinous processes, ribs, shoulders and neck structures are faintly discernible.

- Thin. Fat is built up about halfway on spinous processes. Transverse processes cannot be felt. Slight fat cover over ribs. Spinous processes and ribs are easily discernible. Tailhead is prominent, but individual vertebrae cannot be visually identified. Hook bones (protrusion of pelvic girdle appearing in upper, forward part of the hip) appear rounded, but are easily discernible. Pin bones (bony projections of pelvic girdle located toward rear, mid-section of the hip) are not distinguishable. Withers, shoulders and neck are accentuated.

- Moderately Thin. Negative crease along back (spinous processes of vertebrae protrude slightly above surrounding tissue). Faint outline of ribs is discernible. Fat can be felt around tailhead (prominence depends on conformation). Hook bones are not discernible. Withers, shoulders and neck are not obviously thin.

- Moderate. Back is level. Ribs cannot be visually distinguished, but can be easily felt. Fat around tailhead begins to feel spongy. Withers appear rounded over spinous processes. Shoulders and neck blend smoothly into body.

- Moderate to Fleshy. May have slight crease down back. Fat over ribs feels spongy. Fat around tailhead feels soft. Fat begins to be deposited along the sides of the withers, behind the shoulders and along sides of neck.

- Fleshy. May have crease down back. Individual ribs can be felt, but with noticeable filling of fat between ribs. Fat around tailhead is soft. Fat is deposited along withers, behind shoulders and along neck.

- Fat. Crease down back. Difficult to feel ribs. Fat around tailhead is very soft. Area along withers is filled with fat. Area behind shoulder is filled in flush with rest of the body. Noticeable thickening of neck. Fat is deposited along inner buttocks.

- Extremely fat. Obvious crease down back. Patchy fat appears over ribs. Bulging fat around tailhead, along withers, behind shoulders and along neck. Fat along inner buttocks may rub together. Flank is filled in flush with rest of the body.

Points to Consider

There are several points to consider when using body condition scores.

- Although visual appraisal is the primary tool of the scoring system, accuracy will increase when the areas of fat accumulation can be palpated. Long hair can mask the appearance of fat. Also, different body conformations greatly affect the visual ability to determine body condition. Taller, larger framed horses with prominent withers may appear to be leaner than shorter, smaller framed horses with similar body conditions.

- Mares in late gestation may have less fat cover over the ribs because of the influence of the weight of the fetus and associated tissues. Thus, more emphasis should be placed on other locations of fat accumulation.

- Horses on large percentage forage diets will typically have larger bellies with lower, distended abdomens than horses being managed on grain or in exercise programs. These “hay bellies” can give the appearance of fat, causing overestimation of body condition.

It is important to recognize specific areas on the horse’s body to assess body condition and gain experience in identifying body condition on different horses. Periodic re-evaluations of individual horses will help decrease the influence of conformational differences in body condition assessment.

Body condition cannot be altered significantly in short periods of time. Gains in body weight must be made with gradual increases in the ration. The horse’s body requires time to assimilate increases of energy into fat. Also, the incidence of colic and founder will increase when making dramatic adjustments in the amount of the daily ration. For the thin horse, provide full or free choice quality hay as well as concentrate. Fat-added feeds can assist with weight gain while not feeding excessive concentrate meals. In general, feed at a rate to gain weight at .5 to .75 pounds per day. Environmental stress will increase the length of time and energy intake necessary for increases in body condition.

Weight loss should be considered a gradual process to avoid both behavioral and digestive upsets. Modest weight loss over extended periods is recommended. Diet reductions in 10%-20% calories can lead to successful weight loss. Owners should reduce calorie-rich grains, and restrict access to pasture. Select more mature, lower-calories hay. Intake may need to be restricted to 1.5% of body weight to achieve weight loss. Owners are also encouraged to add exercise conditioning to assist with weight loss, with the added benefit of an increase in insulin sensitivity.

The above examples point out the need to plan well in advance when changing body condition in horses. Under practical management, increasing body condition at times when production needs for energy are high is difficult and costly. Therefore, allow several months for significant increases in body condition. Similarly, allow for gradual decreases in body condition when physically preparing horses for athletic competition, instead of promoting extreme, sudden weight loss by dramatic restriction of energy.

Figure 1. Body Condition 4: Moderately Thin. Note tailhead prominence, negative crease along back, and faint outline of ribs.

Figure 2. Body Condition 5: Moderate. Note shoulders and neck blend smoothly into body. No visual appearance of ribs.

Figure 3. Broodmare in early gestation in Body Condition 6: Moderate to Fleshy. Note fat deposits along sides of withers, behind shoulders and along the sides of the neck.

Figure 4. Body Condition 8: Fat. Crease down back. Difficult to feel ribs. Fat around tailhead is very soft. Area along withers is filled with fat. Area behind shoulder is filled in flush with rest of the body. Noticeable thickening of neck. Fat is deposited along inner buttocks.

Figure 5. Thatcher CD, Pleasant RS, Geor RJ, Elvinger F. Prevalence of overconditioning in mature horses in southwest Virginia during the summer. J Vet Intern Med. 2012;26:1413–8.

Figure 6. Composition grid on camera.