Body Condition Scoring of Cows

Condition Scores

The body condition scoring system is used to assess body energy stores in beef cows. Energy stores are reflected primarily by the relative amount of fat available to metabolize as an energy source. When dietary energy is inadequate to meet the animal’s energy need, fat is mobilized along with some muscle and organ tissue. Said another way, when cows lose weight, they burn fat and some protein tissue (muscle and organ weight).When cows gain weight, they gain primarily fat tissue with minimal gain in protein tissue.

Body condition is important because there is a close relationship between BCS at calving and the first 90 days after calving to reproductive success. In addition, cow body condition influences the calf’s ability to develop a strong immune system.

Current BCS is a snapshot in time of the balance be-tween recent nutrient supply and recent nutrient requirements. Many different management factors influence this balance of supply vs demand. Overgrazing, for example, often leads to a situation where inadequate nutrient supply is available to meet the animal’s requirements, eventually leading to weight loss. Body condition is a good reflection of the match or mismatch of a cow’s genetic potential to the forage and management system.

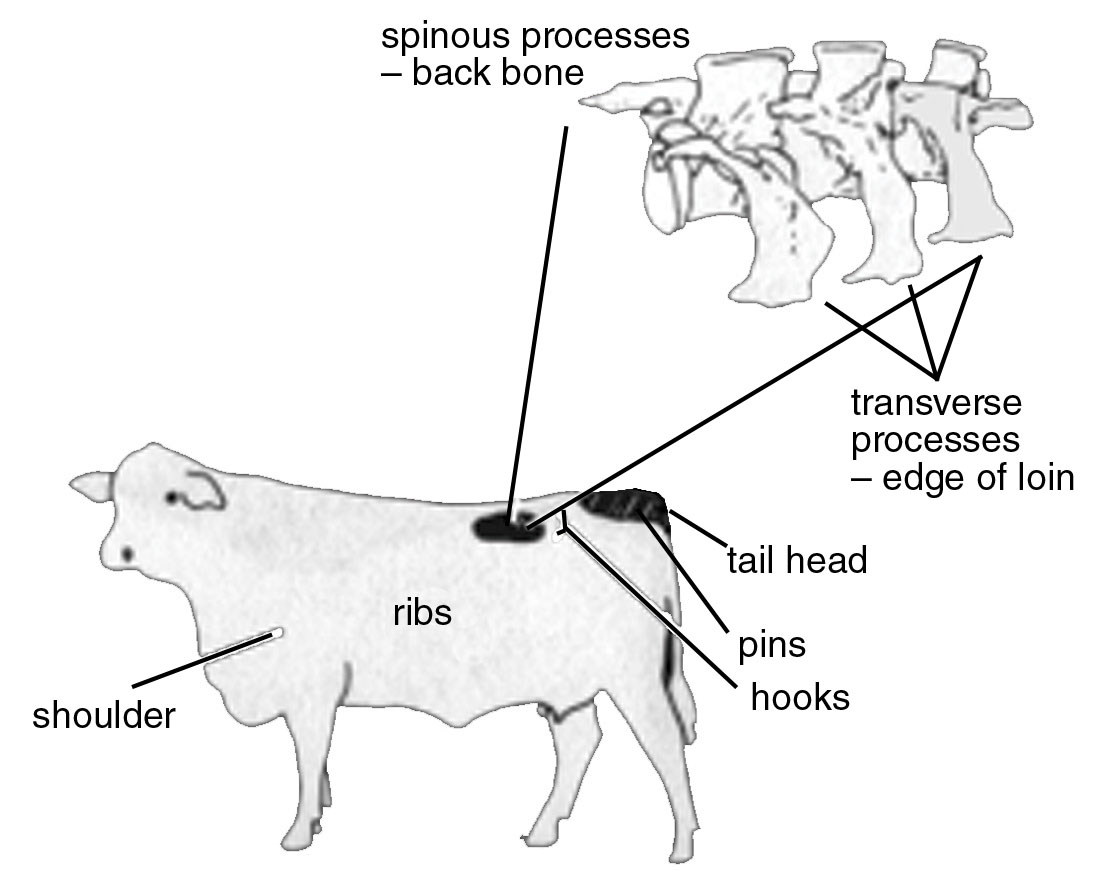

The BCS system used for beef cows ranges from 1 to 9, with a score of 1 reflecting cows that are emaciated and a score of 9 reflecting cows that are obese. Thin cows should receive a lower score and fat cows should receive a higher score. A description of each score follows, and the appearance of key areas of the body is provided in Figure 1.

Cattle descriptions by the nine condition scores follow:

BCS 1. (Figure 2) The cow is severely emaciated and physically weak with all ribs and bone structure easily visible. Cattle in this score are extremely rare and are usually inflicted with a disease and/or parasitism.

Figure 2. BCS 1.

BCS 2. The cow appears emaciated, similar to BCS 1, but not weakened. Muscle tissue seems severely depleted through the hindquarters and shoulder.

BCS 3. (Figure 3) The cow is very thin with no fat on ribs or in brisket and the backbone is easily visible. Some muscle depletion appears evident through the hindquarters.

Figure 3. BCS 3.

BCS 4. (Figure 4) The cow appears slightly thin, with several ribs easily visible and the backbone showing. The spinous processes (along the edge of the loin) are still sharp and barely visible individually. Muscle tissue is not depleted through the shoulders and hindquarters.

BCS 5. (Figure 5) The cow may be described as moderate to thin. The last two ribs can be seen and little evidence of fat is present in the brisket, over the ribs or around the tail head. The spinous processes are smooth and difficult to identify.

BCS 6. (Figure 6) The cow exhibits a smooth appearance throughout. Some fat deposition is present in the brisket and over the tail head. The back appears rounded and fat can be palpated over the ribs and pin bones.

BCS 7. (Figure 7) The cow appears in very good flesh. The brisket is full, the tail head shows pockets of fat and the back appears square due to fat. The ribs are not visible and appear smooth due to fat cover.

BCS 8. The cow is obese. Her neck is thick and her back appears flat or square due to excessive fat. The brisket is distended and large pockets of fat are evident around the tail head.

BCS 9. These cows are extremely obese and may have problems with mobility due to excessive weight and restriction of limbs. The animal’s topline will be square and flat with large dimples or pockets due to excessive fat cover. The front leg set will be wide due to a bulging brisket. The entire underline will bulge with fat, including the udder and naval. The tail head will not be visible as it will be covered in a large mass of fat.

When condition scoring cows, the technician should disregard (or look beyond) age, frame size, rib depth, body length, pregnancy status and hair coat. Condition scoring is intended to provide a consistent system to quantify relative fatness regardless of these other factors that create differences in cows’ appearance.

There is a strong relationship between weight and body condition score. For each one-unit change in BCS, cows should gain or lose approximately 7% of their BCS-5 weight (NASEM, 2016).For example, a cow that weighs 1,200 pounds when she is in BCS 5 should reach a BCS 6 at 1,284 pounds and a BCS 4 at 1,116 pounds.

Why Body Condition is Important

One of the major constraints in the improvement of reproductive efficiency of beef cows is the duration of the post-calving anestrous period. If cows are to maintain a calving interval of one year, they must conceive within 80 to 85 days after calving. Body condition at calving time determines the rebreeding performance of beef cows in the subsequent breeding season to a great extent (Selk).

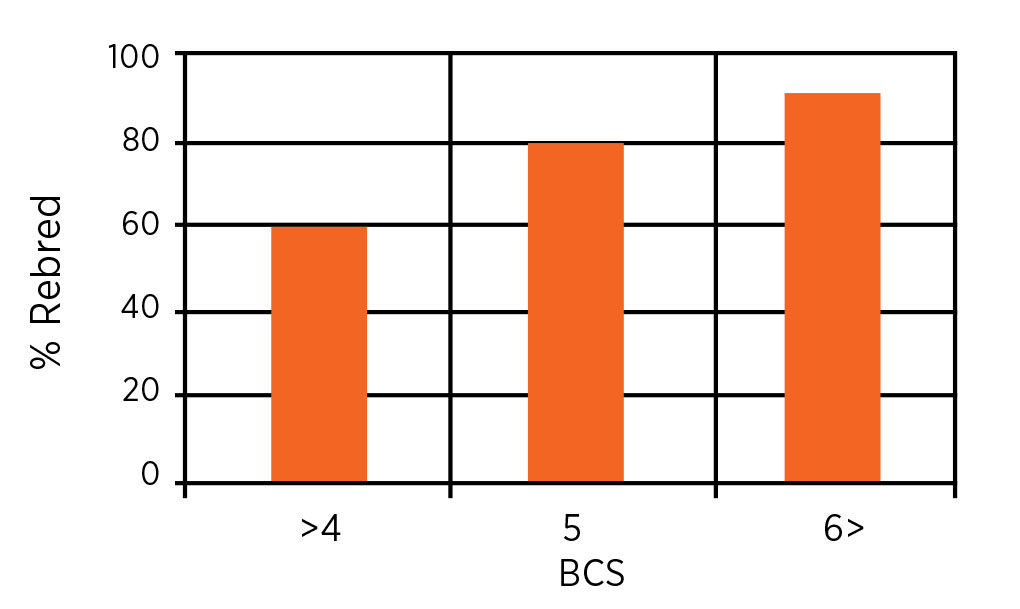

Figure 8. represents the rebreeding percentage of six research herds in four states and includes mature as well as young cows. It clearly shows the body condition at calving greatly determines the rebreeding percentage of cows during the subsequent 60- to 90-day breeding season. Based on research with mature and young cows, those maintaining body weight, therefore, having ample energy reserves before parturition, exhibited estrus sooner than cows that lost considerable body weight and consequently had poor energy reserves. Body weight change during pregnancy is confounded with embryo and placenta growth. Therefore, the estimation of body fat by use of body condition scores is more useful in quantifying the energy status of beef cows. The numeric system of body condition scoring is an excellent estimator of percentage body fat in beef cows. Body condition score accounted for 85% to 91% of the variation in stored body energy (percent fat) in cows.

Figure 8. Percent rebred at next breeding season per day, according to body condition at calving (summary of six trials in four states) BCS 4 or less, BCS 5, BCS 6 or more. Source: Field and Sands.

The processes of fetal development, delivering a calf, milk production and repair of the reproductive tract all are physiological stresses. These stresses require the availability and utilization of large quantities of energy to enable cows to be rebred in the required 85 days. Add to these physiological stresses the environmental stress of cold, wet weather on spring calving cows and the nutritional stress of energy intake that is below body maintenance needs. As the intake falls short of the energy utilized, the cow compensates by mobilizing stored energy or adipose tissue, and through a period of several weeks, a noticeable change in the outward appearance of the cow takes place.

This is a change in the body condition and can be monitored by assigning body condition scores to cows and quantifying the degree of change. Cows in a thin body condition at calving return to estrus slowly. Postpartum increases in energy intake can modify the length of the postpartum interval. However, increases in the quality and quantity of feed to increase postpartum body condition can be very expensive.

Improvement in reproductive performance achieved by expensive postpartum feeding to thin cows may not be ad-equate to justify the cost of the additional nutrients. Oklahoma scientists used 81 Hereford and Angus x Hereford heifers to study the effects of body condition score at calving and postpartum nutrition on rebreeding rates at 90 days and 120 days postpartum (Bell et al.). Heifers were divided into two groups in November and allowed to lose body condition or maintain body condition until calving in February and March. Each of those groups was then divided and fed to gain weight and body condition postpartum or to maintain body condition postpartum.

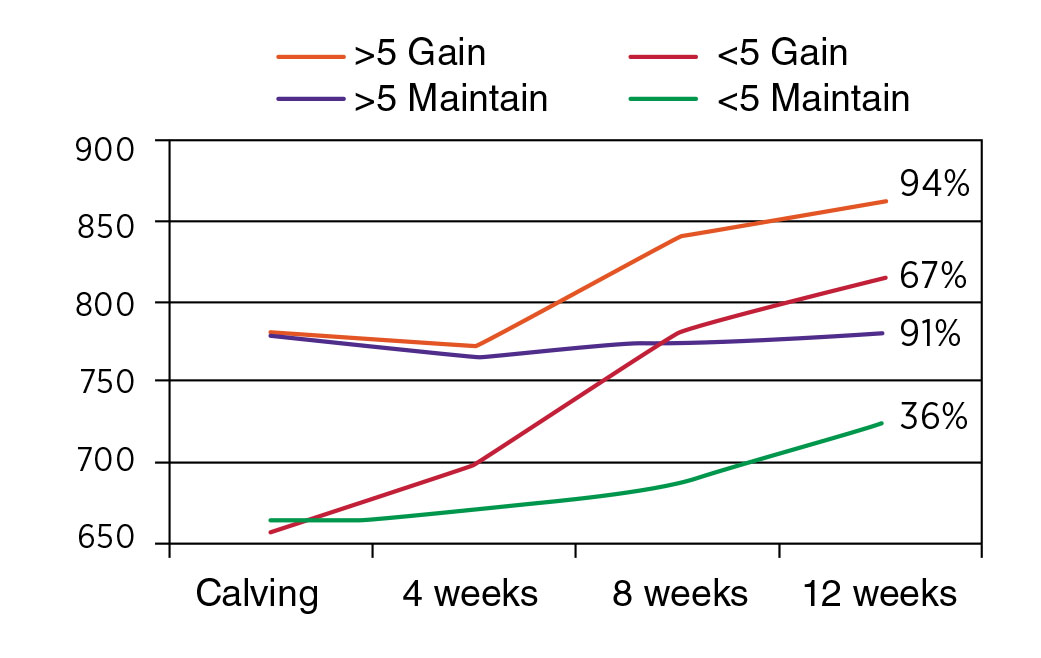

Figure 9. Illustrates the change in body weight of heifers that calved with a greater than BCS 5, or those that calved with a BCS less than or equal to 4.9. The same pattern illustrated in the other experiments is manifested clearly with these heifers. Thin heifers that were given ample opportunity to regain weight and body condition after calving actually weighed more and had greater body condition by eight weeks than those heifers that had good body condition at calving and maintained their weight through the breeding season. However, the rebreeding performance (on the right side of the legend of the graph) was significantly lower for those that were thin (67%) at parturition compared to heifers that were in adequate body condition at calving and maintained condition through the breeding season (91%). Postpartum increases in energy therefore, weight and body condition gave a modest improvement in rebreeding performance, but the increased expense was not adequately rewarded. The groups that were fed to maintain postpartum condition and weight received 4 pounds of cottonseed meal supplement (41% crude protein; $.13 per pound) per day.

Figure 9. Postpartum body weight of heifers with body condition less than 5 or greater than or equal to 5 at calving and fed to gain or maintain weight. Pregnancy rates are indicated on the right side of the legend. Source: Bell et al.

The supplement cost for the 69-day feeding period was approximately $36 per cow. The cows in the gain groups were fed 28 pounds of a grain mix (12% CP; $.073 per pound) at a total supplement cost of $141. Both groups had free choice access to grass hay (Wettemann).The improvement in reproductive performance (67% pregnant versus 36% pregnant) of the thin 2-year-old heifers was not enough to offset the large investment in feed costs in most cases.

Other data sets have shown conclusively cows that calve in thin body condition, but regain weight and condition going into the breeding season, do not rebreed at the same rate as those that calve in good condition and maintain that condition into the breeding season. Table 1 from Missouri researchers illustrates the number of days between calving to the return to heat cycles depending on body condition at calving and body condition change after calving.

This data clearly shows young cows that calve in thin body condition (BCS 3 or BCS 4) cannot gain enough body condition after calving to achieve the same rebreeding performance as cows that calve in moderate body condition (BCS 5.5) and maintain or lose only a slight amount of condition.

Cows must be rebred by 85 days after calving to calve again at the same time the next year. Notice that none of the averages for cows that calved in thin body condition were recycling in time to maintain a 12-month calving interval.

|

BCS at calving |

-1 |

-0.5 |

0 |

0.5 |

1 |

1.5 |

2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

3 |

189 |

173 |

160 |

150 |

143 |

139 |

139 |

|

4 |

161 |

145 |

131 |

121 |

115 |

111 |

111 |

|

5 |

133 |

116 |

103 |

93 |

86 |

83 |

82 |

|

5.5 |

118 |

102 |

89 |

79 |

72 |

69 |

66 |

Table 1. Predicted number of days from calving to first heat as affected by body condition score at calving and body condition score change after calving in young beef cows. (body condition score scale : 1 = emaciated; 9 = obese). Source: Lalman et al.

Conclusion

Producers should manage their calving season, genetics, grazing system, supplementation program and herd health to achieve a herd average BCS of 5 to 6 in mature cows at calving time and BCS 6 in first-calf heifers at calving time. Subsequently, producers should manage their operation with the goal of minimizing the amount of weight and BCS loss between the time of calving and breeding. Early management to meet these goals is important because drastic changes in BCS during late pregnancy and early lactation are extremely difficult and costly to achieve.

References

Bell, D. et al. (1990) Effects of Body Condition Score at Calving and Postpartum Nutrition on Performance of Two-Year-Old Heifers. OSU Animal Science Research Report MP-129.

M.J. Field and R.S. Sand, Eds. Factors Affecting Calf Crop (1994). CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, FL.

Lalman, D.L. et al.(1997) Influence of Weight and Body Condition Change on Duration of Anestrus by Undernourished Suckled Beef Heifers. Journal of Animal Science 75.

Selk, G.E. et al. (1988) Relationships among Weight Change, Body Condition and Reproductive Performance of Range Beef Cows. Journal of Animal Science 66:3153.

Vizcarra, J.A. et al. (1995) Body Condition Score is a Precise Tool to Evaluate Beef Cows. OSU Animal Science Research Report P-943.

Wettemann, R.P. (2004) Personal Communication.