2022-2023 Small Grains Variety Performance Tests

Wheat Crop Overview

At the time of writing this report, 2023 Oklahoma wheat production is estimated to be approximately 54 million bushels, which is about 22% lower than 2022 production and 53% lower than 2021 production (Table 1). Approximately 4.6 million acres were planted for the 2023 crop year, larger than the 2022 crop but 4% lower than the previous 10-year average. Number of harvested acres is estimated at 2.15 million, which is 10% lower than in 2022 (Table 1). The statewide average yield is projected at 25 bu/ac. This is 3 bu/ac lower than the 2022 state average and 8 bu/ac lower than the previous 10-year average.

| 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Planted area | |||

| (million acres) | 4.4 | 4.3 | 4.6 |

| Harvested area (million acres) | 2.95 | 2.40 | 2.15 |

| Yield (bushels/acre) | 39 | 28 | 25 |

| Total production (million bushels) | 115 | 69 | 65 |

Table 1. Oklahoma wheat production for 2021, 2022 and 2023 as estimated by USDA NASS, June 2022. 2021 2022 2023

Dual-purpose wheat producers could not plant at the optimum time (mid-September) due to drought conditions in much of the state. Most of the wheat intended for dual-purpose was “dusted in” and emergence was delayed. Although dual-purpose wheat established well in some areas, October precipitation was insufficient to promote adequate fall forage production, and many producers were not able to graze the wheat in the fall. In some areas producers were able to use wheat for grazing in the spring with a lower stocking rate than usual. Oklahoma received rainfall in October, which helped the dual-purpose wheat to emerge and grow as well as enabled grain-only producers to plant under good soil moisture in some areas.

December was warmer than usual with large fluctuations in temperature and a few days below 32 degrees. By the end of year, the wheat was small and showing signs of drought stress and could have benefited from additional moisture going into the winter. However, this moisture did not arrive until February except in the NW and NC regions.

Due to a lack of moisture late in the fall, wheat fields planted late, especially the northcentral, northwest, and Panhandle regions, did not emerge until February. This resulted in reduced growth and tillering. The continual lack of rainfall during the winter made conditions unsuitable for wheat, and growers could not take the crop to grain harvest. Many producers decided to cut wheat for hay or had to abandon the fields. There were few dryland wheat fields harvested in the Panhandle. In other parts of the state where the crop was established in October and received some rainfall in February, April, and May, yield potential was acceptable. However, with the exception of eastern OK, much of the wheat in the state was grown under chronic drought stress. No diseases or insects of any significance were observed in the fall.

Overall, average temperatures and extremely low rainfall resulted in small fall forage production (for more information see CR 2141 - Fall Forage Production and First Hollow Stem Date for Small Grain Varieties during the 2022-2023 Crop Year). Lack of moisture resulted in late wheat emergence, slow plant development, and delayed onset of first hollow stem for our region. This deficit also may have compressed differences among varieties for onset of first hollow stem. In the forage trials, the very early genotypes reached first hollow stem during the first week of March and most of the very late genotypes reached first hollow stem during the second week of March. By the end of March drought conditions became severe in many areas, and the crop was behind in growth in much of the state. Some parts of the state received decent rainfall at the beginning of April -- the most significant received since planting. This moisture saved many producers from not having a crop in 2023. However, some places, such as the panhandle and northwest regions, did Division of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources • Oklahoma State University not receive significant amounts of precipitation. Moisture deficit during this critical plant developmental stage (from jointing to flag leaf stage) resulted in short wheat in many fields. Flag leaves turned blue and curled due to lack of moisture. The weather continued to be very hot and dry and prevented the emergence of many diseases. However, moderate infestations of brown wheat mites occurred in the northern part of the state.

Wheat started to head by mid-April in southwest OK and late April in southcentral OK. Freeze events occurred but the damage was minimal this year. Some fields showed heads with discoloration (i.e., bleached) due to different types of stresses (e.g., freeze, drought, and crown/root rots). By May, the crop received significant amounts of precipitation, which was crucial to help with grain filling and test weight.

Late in March, wheat soilborne mosaic and wheat spindle streak mosaic were observed in a few research trials in Stillwater and Lahoma. Symptoms of these viral diseases disappeared as temperatures increased in April. In contrast to 2022, wheat streak mosaic was rarely observed and only a couple of infected samples were reported in Payne and Woods Counties late in March. Barley yellow dwarf, which is a common viral disease in Oklahoma, occurred at moderate incidence and severity during mid-April to mid-May.

As in 2022, common root rot (caused by Bipolaris sorokiniana) and Fusarium root and crown rot were severe throughout the growing season in multiple wheat fields in western Oklahoma where drought was prevalent. Root rots were observed in fields in multiple counties including Jackson, Woods, Kingfisher, Washita, Grant, Ellis, Grady, and Garfield.

Fungal foliar diseases were not noticeable until May due to severe drought. The precipitation in May promoted the development of some foliar fungal diseases, but it was late in the growing season to cause significant impact on yield. Among these foliar fungal diseases, spot blotch, Septoria tritici blotch, and Stagonospora leaf and glume blotch were observed in moderate incidence and severity with occasional fields showing high severity. These leaf spotting diseases were reported in Payne, Garfield, Major, Okmulgee, Cleveland, and Grady counties. Powdery mildew was another foliar fungal disease that was observed in low incidence and severity in Payne and Okmulgee counties.

Stripe rust was first reported in low incidence and severity at the OSU South Central Research Station in Chickasha (Grady County) during the last week of April. Later in May, stripe rust was observed in trace levels at Stillwater (Payne County), but it was not a concern in Oklahoma wheat fields. The rainfall in May also favored the appearance of leaf rust that was observed in low incidence and severity at Stillwater and Lahoma. The highest incidence and severity of leaf rust were observed at the OSU South Central Research Station at Chickasha during midto late-May, with oderate to significant yield loss depending on resistance level. Leaf rust, however, did not appear to inflict widespread damage on the Oklahoma wheat crop. Stem rust, which is rarely observed in Oklahoma, was first reported at Chickasha during the third week of May. Stem rust hot spots were found on the wheat cultivar ‘LCS Galloway AX’ and a few other susceptible breeding lines from the Great Plains. Infected stem rust samples were sent to the USDA-ARS Cereal Disease Lab in Minnesota for race identification. The stem rust pathogen race was confirmed to be QFCSC which has been a dominant race in the USA for many years. This race was also found from earlier collections this year in Louisiana and Texas. There were no other reports of stem rust in Oklahoma wheat fields.

There were reports of nematodes and bacterial diseases in a few wheat fields in Oklahoma. During late March-early April, plant parasitic nematode species were recovered from a couple of soil and wheat samples collected from yellowing spots in wheat fields in Blaine and Ellis Counties. There were not many reports of nematode problems in wheat in Oklahoma in previous years, so future investigations will continue in coming seasons. Precipitation during May also favored the appearance of bacterial diseases including bacterial leaf streak that was confirmed in a sample from Morris (Okmulgee County). Bacterial leaf blight was observed in a couple of samples collected in Stillwater (Payne County) and Morris; however, this disease is not of major economic importance as the causal bacterium is considered a weak pathogen.

In summary, this year’s crop was thin and short, with small head size due to the severe drought it experienced throughout the season. Kernel size, however, benefitted from precipitation events during May. Overall, the Oklahoma wheat crop was severely affected by lack of moisture, and some fields were not harvested.

Most of the rain in the state came in the first two weeks of May and continued until July. Consequently, harvest was delayed by a couple of weeks in some areas and weed pressure was problematic. According to the Oklahoma Wheat Commission report, grain yields of harvested wheat ranged from meager yields (10 bu/ac) in drought-stressed fields to higher yields (60-80 bu/ac) in intensively managed and irrigated fields. Test weight was good as harvest began, with values ranging from 58 to 61 lbs/bu. Wheat protein varied from 11 to 14% across the state, with a state average of 13%.

Testing Methods and Data Interpretation

Testing Methods

Seed was packaged and planted in the same condition as delivered from the respective seed companies. Most seed was treated with an insecticide plus a fungicide, but the formulation and rate of seed treatment used was not confirmed or reported in this document.

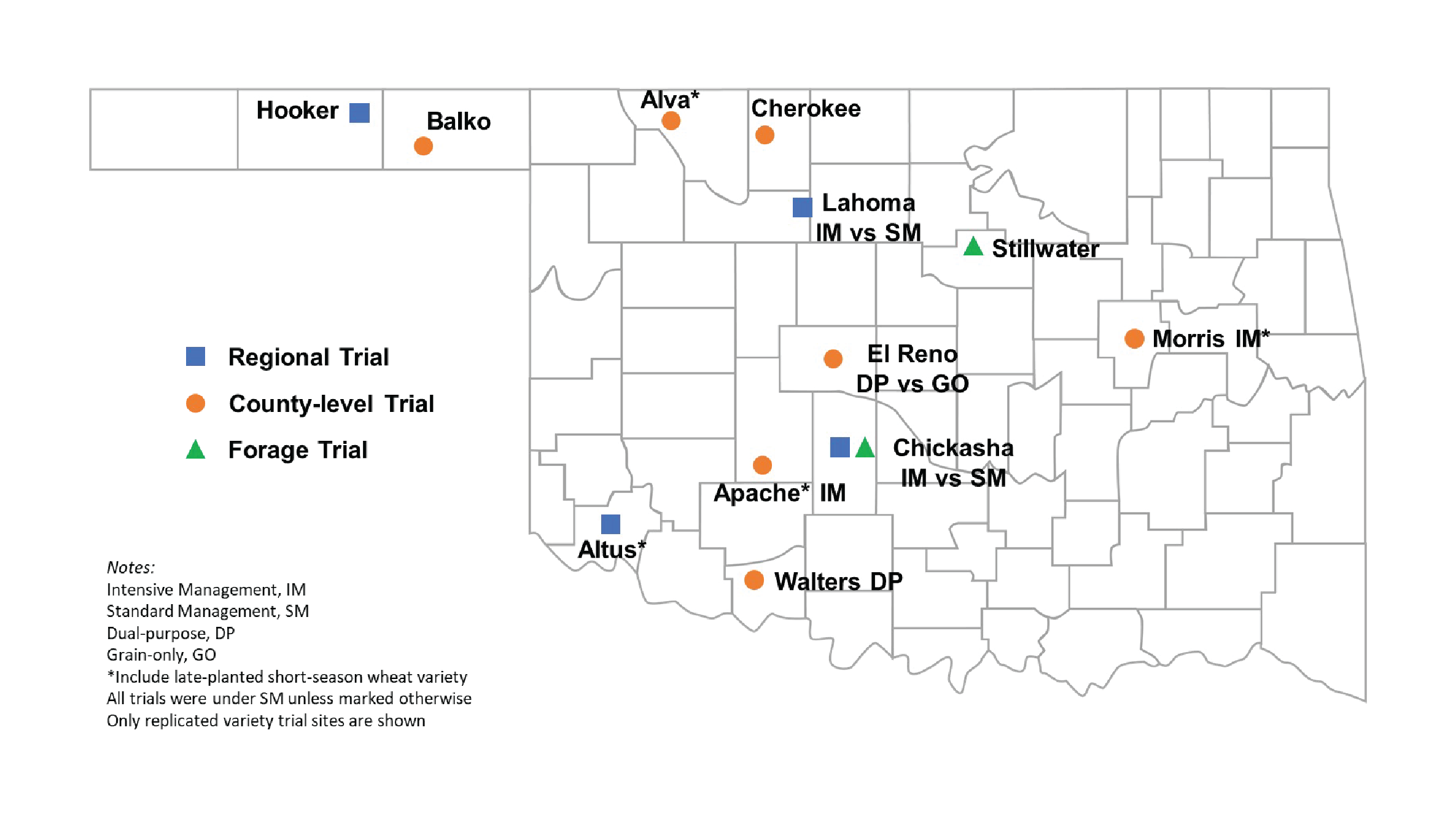

Plots were seven rows wide with 7.5-inch row spacing and were sown with a Great Plains no-till drill modified for cone-seeded, small-plot research. Except for dryland locations in the Panhandle, plots were planted 25 feet long and trimmed to 19 feet at harvest with the plot combine. Panhandle dryland locations were 35 feet long at planting and trimmed to 29 feet at harvest. Wheel tracks were included in the plot area for yield calculation for a total plot width of 60 inches. The experimental design for all sites was a randomized complete block with four replicates. The intensive management trials at Apache, Morris, Chickasha, and Lahoma received two fungicide applications, additional topdress nitrogen application in the spring, and were planted on a seeds per acre basis at 1.2 million seeds per acre. Fungicide was applied at Feekes 6 (jointing) and Feekes 9 (flag leaf completely emerged). Additional information on product name, rate and date of application is included in the tables for the respective sites.

Plots received 5 gal/ac of 10-34-0 at planting. All variety trial locations were sown at 60 pounds per acre, except for the dual-purpose trials at El Reno and Walters, which were sown at 120 pounds per acre. The intensive wheat management trials at Apache, Chickasha, Lahoma, and Morris were sown at 1.2 million seeds per acre. Grazing intensity, nitrogen fertilization, and insect and weed control decisions were made on a location-by-location basis and reflect standard management practices for the area. In general, the spring-applied N rate was calculated for a 70 bu/ac yield goal for the standard management trials and 100 bu/ac yield goal for the intensive management trials. Plots were harvested with a Winterstieger Delta small plot combine. Grain weight, test weight, protein concentration, and moisture content were collected from each plot, and grain yields and protein concentration were corrected to 12% moisture content. Grain moisture at all sites was generally below 12%, and maximum and minimum grain moisture for all plots at a location typically ranged no more than 2%. Similar to many wheat fields in the region, the Hooker trial experienced severe drought stress throughout the growing season, with significant plant mortality. Thus, this site was not harvested in 2023.

Data Interpretation

Yield, test weight, and protein data for each location and regional summary were analyzed using the appropriate statistical methods. At the bottom of each table, the mean and least significant difference (LSD) values are reported. The LSD is a test statistic that aids in determining whether there is a true difference in yield, test weight, and protein. In this report, one can be 95% confident that the difference between two varieties is real if the difference is greater than the LSD value. Data that is not significantly different is indicated by “NS”. For example, if the LSD value is 4 bu/ac in a trial where Variety A yielded 30 bu/ac and Variety B yielded 25, then Variety A would be considered to have a statistically higher yield. However, if Variety C yielded 27 bu/ac, then Variety A and Variety C would be considered to have a similar yield. In that same example trial, there is a 5% chance that the 4 bu/ac difference between Variety A and Variety B does not truly exist, but random chance caused the 5 bushel difference. These chance factors may include differences in fertility, moisture vailability, and diseases. To aid in visualizing the varieties with the highest yields, test weights, and proteins, values highlighted in gray do not differ statistically from the highest value within a column. The performance of a variety may vary from year to year, even at the same location. Tests over two or more years and over multiple locations more accurately predict the performance of a variety.

Additional Information on the Web

A copy of this publication as well as additional information about wheat management can be found at:

Website: www.wheat.okstate.edu

Blog: www.osuwheat.com

Facebook: @OSU_smallgrains

Twitter @OSU Small Grains

To view all tables, see the available PDF version

Authors

- Amanda de Oliveira Silva | Small Grains Extension Specialist

- Tyler Lynch | Senior Agriculturalist

- Israel Molina Cyrineu | Graduate Research Assistant

- Samson Abiola Olaniyi | Graduate Research Assistant=

- Dr. Brett Carver | Wheat Breeder

- Dr. Meriem Aoun | Small Grains Pathologist

Funding Provided By

- Oklahoma Wheat Commission

- Oklahoma Wheat Research Foundation

- OSU Cooperative Extension Service

- OSU Agricultural Research

- Entry fees from participating seed companies

Area Extension Staff

- Brian Pugh | OSU Area Agronomist – Northeast District

- Josh Bushong | OSU Area Agronomist – Northwest District

- Gary Strickland | Southwest Research and Extension Center Regional

Agronomist and Jackson County Extension Educator - Summit Sharma | Assistant Extension Specialist - Oklahoma Panhandle

Research and Extension Center, Goodwell

County Extension Staff

- Thomas Puffinbarger | Alfalfa County Extension Educator

- Loren Sizelove | Beaver County Extension Educator

- Alyson Pitmon | Caddo County Extension Educator

- Kyle Worthington | Canadian County Extension Educator

- Kimbreley Davis | Cotton County Extension Educator

- Rick Nelson | Garfield County Extension Educator

- Denise Wood | Grady County Extension Educator

- Shannon Mallory | Kay County Extension Educator

- Bryan Kennedy | Kingfisher County Extension Educator

- Tanner Miller | Okmulgee County Extension Educator

- Dr. Britt Hicks | Texas County Extension Educator & Area Extension

Livestock Specialist - Greg Highfill | Woods County Extension Educator

Station Superintendents/Staff

- Erich Wehrenberg | Agronomy Research Station, Stillwater, Lahoma

- David Victor | North Central Research Station, Lahoma

- Michael Pettijohn | South Central Research Station, Chickasha

- Mike Schulz, Blake Sisson, Greg Chavez | Southwest Research and Extension Center, Altus

Student Workers and Visiting Scholars

- Cassidy Stowers

- Camila Bayer

- Laercio Pivetta

- Oluwatobi Quadri

Partial financial support provided by the Oklahoma Wheat Commission and the Oklahoma

Wheat Research Foundation.

Participating Seed Companies

AgriMAXX Wheat Company

Matt Wehmeyer

7167 Highbanks Road

Mascoutah, IL 62258

Phone: (855) 629-9432

Email: matt@agrimaxxwheat.com

www.agrimaxxwheat.com

Variety: AM Cartwright

AgriPro

Greg McCormack

8750 NW 66th st.

Silver Lake, KS 66539

Phone: (620) 532-6283

Email: greg.mccormack@syngenta.com

www.agriprowheat.com

Varieties: AP EverRock, AP Bigfoot, AP Longjack, AP Prolific, Bob Dole, SY Wolverine

AGSECO, Inc.

Steve Ahring

P.O. Box 7

Girard, KS 66743

Phone: (620) 724-6223

Email: steve@delangeseed.com

www.agseco.com

Varieties: AG Golden, AG Radical

CROPLAN by Winfield United

Cameron Aker

500 North 1st street

Vincent, IA 50594

Garrison, ND 58540

Phone: (515) 356-4524

Email: claker@landolakes.com

www.croplan.com

Varieties: CP7017 AX, CP72166 AX

Kansas Wheat Alliance (KWA)

Bryson Haverkamp

1990 Kimball Ave. Suite 200

Manhattan, KS 66502

Phone: (785) 320-4080

Email: kwa@kansas.net

www.kswheatalliance.org

Varieties: KS Ahearn, KS Providence

Limagrain Cereal Seeds (LCS)

Daniel Dall

1250 N Main St.

Benton, KS 67017

Phone: (316) 452-3505

Email: daniel.dall@limagrain.com

www.limargraincerealseeds.com

Varieties: LCS Atomic AX, LCS Chrome, LCS Helix AX, LCS Julep, LCS Photon AX, LCS

Galloway, LCS Steek AX

Oklahoma Genetics, Inc. (OGI)

Mark Hodges

201 South Range Road

Stillwater, OK 74074

Phone: (405) 744-4347

Email: hodgesm1@cox.net

www.okgenetics.com

Varieties: Baker’s Ann, Bentley, Big Country, Breakthrough, Butler’s Gold, Doublestop

CL+,

Gallagher, Green Hammer, High Cotton, Iba, Lonerider, OK Corral, Showdown, Smith’s

Gold, Strad CL+, Uncharted

PlainsGold (Colorado Wheat Research Foundation)

Brad Erker/Tyler Benninghoven

4026 S. Timberline Road Suite 100

Fort Collins, CO 80525

Phone: (970) 449-6994

Email: tbenninghoven@coloradowheat.org

www.plainsgold.com

Varieties: Breck, Canvas, Crescent AX, Kivari AX

WestBred

John Fenderson /Lance Embree

1616 E. Glencoe Road

Stillwater, OK 74075

Phone: (620) 243-4263

Email: john.fenderson@bayer.com

www.westbred.com

Varieties: WB4401, WB4422, WB4523, WB4632, WB4792

Partial financial support provided by the Oklahoma Wheat Commission and

the Oklahoma Wheat Research Foundation.