What Drives Small Town Population Growth in Oklahoma?

Introduction

Most of the towns in Oklahoma are small. In fact, of the 598 incorporated places listed by the Oklahoma Department of Commerce, 522 (87 percent) had populations under 5,000 as of 2010. However, the economic outlook and vitality of these small towns is highly variable. Many of them have lost (or are losing) population, while others are growing rapidly. The purpose of this fact sheet is to observe trends in small town population growth across Oklahoma during the period 1980 to 2010, and to determine the most important factors underlying why towns either grew or shrank during that time.

There are several reasons why population growth matters for small towns. First, it

provides and sustains a tax base to pay for local government services, such as the

school system, roads and police and fire departments. Second, it can help to maintain

a sense of place for those unable or unwilling to leave. Finally, it can perpetuate

the culture making that place unique – and studies have found that small town “character”

is an important component of a community’s existence (Good, 2002). This character

is comprised of social, economic and physical factors; all of which can be strengthened

as a town grows. For example, the town of Pawnee in central Oklahoma has seen a 30

percent increase in population since 1980, thanks in part to the legacy of Pawnee

Bill and an ability to work with the local tribal government.

The reasons behind the different population outcomes for small towns are varied. Historically,

many rural areas across the nation lost population as residents left for the jobs

and experiences in bigger cities (Johnson, 2006). That began to change in the 1970s

when a “rural rebound” occurred and rural areas began to grow faster than their urban

counterparts. Since then, the total population change in non-metropolitan counties

has cycled up and down (Figure 1). Several studies have explored these trends. Johnson

(2006) points out that farming is no longer the dominant source of employment in rural

areas, and notes that population declines have been dramatic across many farming-dependent

communities. He also notes the importance of natural amenities, such as recreational

opportunities or scenic landscapes; and finds that many non-metropolitan areas that

benefit from these attributes have seen significant population growth. For example,

the community of Grove in northeast Oklahoma has grown from 3,500 population in 1980

to over 6,500 in 2010, likely in part due to its proximity to Grand Lake. Other recent

articles have pointed to the growth of nearby larger cities, and emphasized that the

fate of smaller, outlying towns are driven by the success of the larger region (Henderson,

2017). An example of this in Oklahoma is the town of Coweta (on the outskirts of Tulsa),

which has more than doubled their population since 1980 and is now home to over 10,000

people. Cohen (2013) argues that the child-bearing age population is important for

small towns, suggesting that youths leaving for bigger cities and declining birth

rates are impacting rural areas. Thus, there are many factors that could influence

small town population growth, including access to a nearby metropolitan area (and

the jobs found there), demographic characteristics of the residents and built/natural

environmental factors (Johnson, 2006).

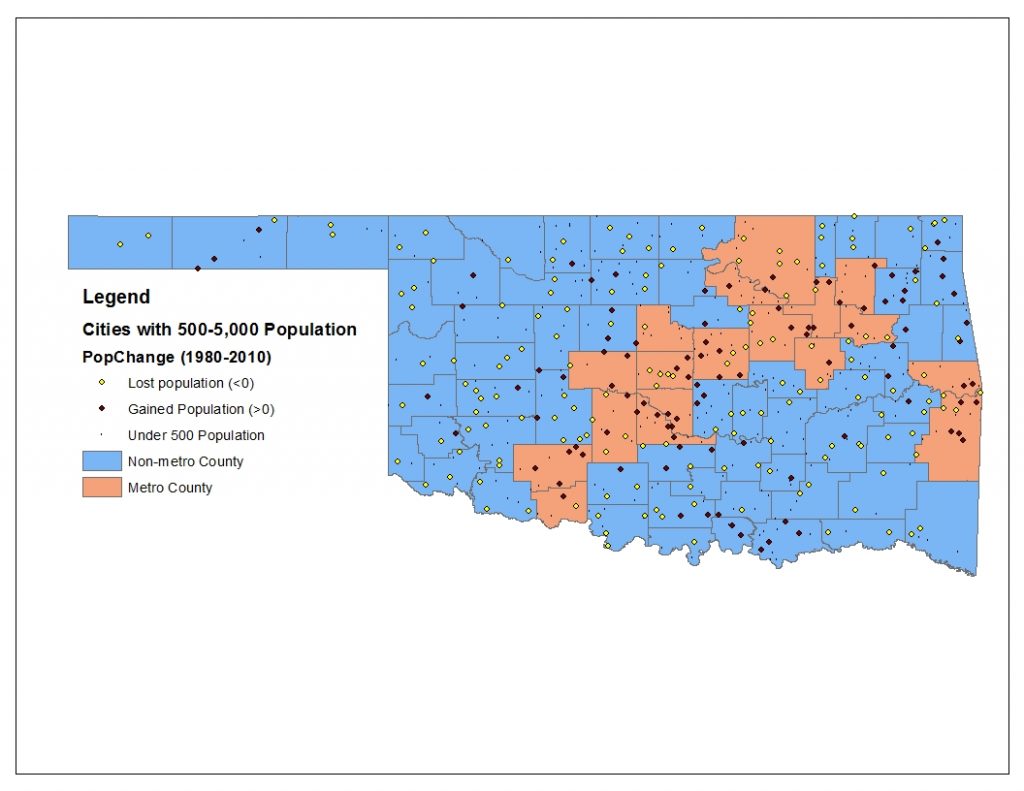

Figure 2 displays Oklahoma cities with populations between 500 and 5,000 as of 1980,

and whether their population has increased or decreased since that time. Of the 266

cities represented, 165 (62 percent) have lost population since 1980, while the remaining

101 (38 percent) gained population. One clear pattern emerges from this map: over

half (54) of the small towns that have gained in population are located in the swath

of metropolitan counties that runs from the northeast corner of the state to the southwest.

Thus, proximity to a metropolitan area would seem to be an important factor for this

analysis. However, as noted above, other factors could also be significant – such

as the economic dependency of the county or the percentage of the population classified

as young.

The remainder of this fact sheet details the data used for the analysis, then demonstrates

simple population trends associated with specific individual factors (for example,

documenting average population growth for cities in a farm-dependent county or plotting

population growth vs. distance from a major metropolitan city). Finally, it uses regression

analysis to uncover which of the factors discussed are responsible for driving most

of the population growth during this time period.

Figure 1. Non-metropolitan population change, 1976-2016.

Figure 2. The 1980-2010 population growth for Oklahoma towns with 500 to 5,000 population as of 1980.

Data and Methods

The data for this report is gathered from a variety of publicly available sources. The primary source of information regarding population change comes from the Oklahoma Department of Commerce. They provided an excel file for 1890-2010 census population by place by county. The analysis in this paper is focused on the 1980-2010 time period. Other data includes the county typology codes defined by the USDA Economic Research Service. These codes classify U.S. counties into categories of economic dependence (farming, mining, manufacturing, government, services and non-specialized) based on the percentage of earnings and/or employment in those sectors (ERS, 2018a). Similarly, they classify counties into policy types (such as low-education or retirement destination) based on census data for specific years. The 1989 county typology codes were used for this research.

The ERS also provides a county-level natural amenity scale, which measures characteristics

of a county (climate, topography, water area) that can represent the environmental

preferences of most people (ERS, 2018b). Oklahoma counties rank from a 3 to a 5 on

the 7-point ERS scale; all counties scoring a 5 were classified as “high natural amenity”(only

four counties across the state). These counties generally have access to a lake (such

as Lake Texoma or Carter Lake) and also have a state park or wildlife refuge nearby

(such as Sequoyah State Park). Additionally, the importance of having a youthful population

was measured by assessing the share of the county population comprised of 25- to 44-year-olds

in 1980. Finally, the distance from each city to the closest metropolitan statistical

area of 50,000 or more (in 1980) was measured. Each of these factors may influence

population growth on their own, and the next section explores these simple relationships.

Table 1 shows significant differences in these variables across cities that gained/lost

population between 1980 and 2010. For example, 29 percent of the cities that lost

population are located in a county classified as farming dependent, while that categorization

applies to only 6 percent of cities that gained population. Alternatively, 14 percent

of the cities that gained population are considered service dependent, compared to

only 7 percent of cities that declined. Similarly, cities that gained population are

more likely to be located near a metropolitan area and have a higher percentage of

youth. To assess which of these influential variables are the drivers of population

growth, a more involved statistical technique known as multivariate regression was

used.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for Oklahoma cities that gained/lost population between 1980-2010.

| Average: Lost Pop |

Average: Gained Pop |

Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farm_Dep | 0.2909 | 0.0594 *** | 0 | 1 |

| Manuf_Dep | 0.0303 | 0.0792 *** | 0 | 1 |

| Mining_Dep | 0.0424 | 0.0396 | 0 | 1 |

| Service_Dep | 0.0727 | 0.1386 ** | 0 | 1 |

| Retirement | 0.0061 | 0.0297 * | 0 | 1 |

| Metro_Adj | 0.2848 | 0.3465 | 0 | 1 |

| Hi_Nat_Amen | 0.0182 | 0.0297 * | 0 | 1 |

| Miles_to_Metro | 59.98 | 50.15 ** | 2.76 | 259.06 |

| Youth_index (% 25 to 44) | 0.2454 | 0.2577 *** | 0.1888 | 0.3314 |

| Number of Cities | 165 | 101 |

*, ** and *** indicate statistically different means at the p<0.10, 0.05 and 0.01 levels, respectively.

Results

Figures 3 to 6 display charts showing the relationship between average growth rates of cities and several distinct categories. Figure 3 shows that a wide variation in average growth rates exists for cities in counties that fall into different categories of economic dependency, as defined by the ERS. For example, the 54 cities in farming dependent counties in the dataset saw their population drop by an average of 18.31 percent between 1980 and 2010. Alternatively, 13 cities located in manufacturing-dependent counties saw average population gains of 15.96 percent during this time period. The 26 cities in service-dependent counties showed slight population gains (2.39 percent), while the 11 cities in mining-dependent counties were associated with slight losses (-4.55 percent). Thus, there is some evidence that towns in manufacturing-oriented counties have seen higher growth, while those in farming or mining-focused locations have generally declined.

Figure 4 looks at 1980-2010 population growth across two specific typologies and location

in, or proximity to, a metropolitan county. The 65 cities located in metropolitan

counties display an average growth rate of over 46 percent, while the 82 cities in

counties adjacent to metropolitan counties had growth rates of just 1.75 percent.

Alternatively, cities in non-metro counties that are not adjacent to metro areas had

average growth rates of -11.1 percent. The four cities in counties classified as retirement

destinations saw growth rates of 26.9 percent, and those classified as high natural

amenities saw 15.9 percent population growth during this period. Again, these statistics

suggest that cities in specific types of counties are more likely to see positive

population change.

Figure 5 demonstrates a negative relationship between the 1980-2010 population change

and the number of miles to the nearest metropolitan location of 50,000 or more. Note

that the vast majority of towns located within 25 miles of a metropolitan city saw

positive population change, and that most located more than 150 miles away saw population

loss. Thus, being further away from a major city is associated with losing population.

Finally, Figure 6 shows that cities with a higher proportion of youth population as

of 1980 had a higher population growth rate during the next 30 years, implying that

the age composition of a town may be an important determinant of population change.

Figure 3. The 1980-2010 population growth rates by economic dependency categories.

Figure 4. The 1980-2010 population growth rates by policy/metro categories.

Figure 5. The 1980-2010 population growth rates and distance to nearest metropolitan area (miles).

Figure 6. The 1980-2010 population growth rates and percentage of 1980 population, aged 25 to 44 (%).

Regression Results

While Figures 3 through 6 show that some specific characteristics do appear to influence population growth, the simple statistics displayed do not take other factors into consideration. For example, farming-dependent communities tend to lose population, but what about those that are relatively close to a metro area? Cities in areas with high natural amenities tend to see population growth, but what if they have a very low youth population? To single out the impacts each particular factor might have on population change, a technique known as multivariate regression analysis is used. Regression analysis is a statistical process that estimates the relationships among several variables. It can explain how much of the 1980-2010 population change is associated with each of the factors discussed above.

Table 2 displays the results of the regression analysis. The dependent variable is

the percentage of population change between 1980 and 2010 for each city. If a particular

characteristic is associated with a positive (or negative) population change, the

corresponding variable would have a statistically significant coefficient. This indicates

that it is not very likely that the relationship is due to chance.

The results of Table 2 show that only three variables (farming dependence, miles to

a metro city and youth percentage) have a statistically significant relationship with

1980-2010 population change. The remaining variables (mining/manufacturing/service

dependence; retirement counties; metro adjacency and high natural amenities) all lack

significance, indicating that they have no meaningful influence on population change

when other variables are considered.

Table 2. Regression results: Determinants of small town population growth.

| Coeff | |

|---|---|

| Farm_Dep | -0.181 * |

| Mining_Dep | -0.234 |

| Manuf_Dep | 0.125 |

| Service_Dep | -0.048 |

| Retirement | 0.341 |

| Metro_Adj | -0.048 |

| Hi_Nat_Amen | 0.127 |

| Miles_to_Metro | -0.002 *** |

| Youth (% 25 to 44) | 3.911 *** |

| Constant | 0.713 * |

| R2 | 0.136 |

| Number of Observations | 266 |

* statistical significance at the p<0.10 level

*** statistical significance at the p<0.01 level

The two variables with the highest level of statistical significance are at the city level: miles to the nearest metropolitan city (with a coefficient of -0.002) and the percentage of residents aged 25 to 44 (with a coefficient of 3.911). To interpret the associated coefficients, first recall that the population growth variable ranged from -0.99 to 3.50 (i.e. losing almost all population to a 350 percent increase). The coefficient on ‘Miles_to_Metro’ indicates that for each mile away from a major city of 50,000 or more, the population change variable decreases by .002. So, a town that is 100 miles away from a major city will see a 0.2 percent decrease in population growth when compared to an otherwise identical town located right next to a major city. Similarly, a town with a 1 percent higher proportion of the population aged 25 to 44 in 1980 would realize a 3.9 percent increase in population over the 30-year period. The only other variable that is statistically significant is the county-level farming-dependency category. This coefficient shows that cities in these counties will experience an 18 percent decrease in population when compared to a similar town that is not in a farming-dependent county.

Discussion

The results presented in this fact sheet point suggest that proximity to a major city; having more young, working-age people and not being in a farm-dependent county encourage population growth. Arguably, a city cannot, at least in the near term, affect its location characteristics. It can, however, encourage economic development activities to change the dominant industries in the county. Additionally, it can become a place that young people want to stay in/return to. Indeed, some of the population growth stimulated is people returning home to raise their families – because there is a support network of parents/family still in town and/or familiarity and perceived security in a small town setting. Therefore, cities should invest in economic development and quality of life to encourage population growth – particularly trying to attract those in the 25 to 44 age category. A good example in Oklahoma is the town of Tuttle, which recently invested in a fiber optic network capable of providing super-fast internet to the entire town. One approach to reaching this younger demographic is to have a writing program that maintains contact with local high school graduates that have left the area. Regular contact such as reminders of important events in the community, happy birthday wishes or announcements of local jobs maintains a connection with these individuals and reminds them of the community they may want to return to. Good broadband access, low crime rates, highway access and the availability of food options (including new restaurants or food trucks) are also important quality of life considerations for this demographic that can be emphasized with a writing program. Some communities have even given local high school graduates their own mailbox with the idea that they will always have a place in the community. Another approach involves engaging current community members (including youth) to consider what local assets might attract potential new residents, then building and implementing a marketing action plan (Welte, 2017). Some medical centers also have programs that encourage rural youths to pursue careers in health care – and then return to their rural roots (UNMC, 2018).

Several recent studies highlight similar findings in discussing population changes

in small towns. Winchester (2009) confirms that small town communities can make an

effort to attract people by emphasizing quality of life. He found that rural areas

in Minnesota benefited from in-migration of 30- to 49-year-olds; often with high levels

of education or skills. These individuals and families were looking for a simpler,

safe and secure life; suitable housing; outdoor recreation and quality schools. They

specifically mentioned being worn down by city life and wanting access to amenities

such as state parks. Similarly, Cromartie and Nelson (2009) emphasize that migration

rates shift geographically during working years, with married couples placing premiums

on residential space, quality schools and feelings of safety. Johnson et al. (2005)

show that in-migration and out-migration “hotspots” can shift over time, particularly

for age-specific cohorts (like those aged 25 to 44). This suggests that cities and

regions can potentially overcome their location handicap.

There may be several other factors not included in this analysis that are important

for explaining small town population growth, such as land value, school quality and

local tax rates (Trotter, 2011). However, the results here demonstrate that proximity

to a major city and having a young population base are important aspects to consider.

Cities interested in increasing their population should take a proactive approach

to improving the local economy and overall quality of life in their communities, while

being aware of the factors that influence their growth potential. Writing programs

that reach out to local graduates and former residents can be an important component

of this work, as can efforts to bring in amenities that appeal to a younger population

base.

References

Cohen, Norma. 2006. “Rural US shrinks as young flee for the cities” Financial Times. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/e213f016-c9d7-11e2-af47-00144feab7de

Cromartie, John and Peter Nelson. 2009. “Baby Boom Migration and Its Impact on Rural

America.” ERR-79, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

Economic Research Service. 2018a. “County Typology Codes: Documentation.” United

State Department of Agriculture. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/county-typology-codes/documentation/

Economic Research Service. 2018b. “Natural Amenities Scale: Overview.” United States

Department of Agriculture. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/natural-amenities-scale/

Good, Karen. 2002. “Preservation of Small Town Character in the Town Center of Rutland, Massachusetts,” Landscape Architecture & Regional Planning Masters Projects. Available online: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1035&context=larp_ms_projects

Henderson, Tim. 2017. “While Most Small Towns Languish, Some Flourish.” The Huffington Post. Available online: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/while-most-small-towns-languish-some-flourish_us_595cf0fde4b0f078efd98d80

Johnson, Kenneth, Paul Voss, Roger Hammer, Glenn Fuguitt and McNiven, Scott. 2005.

“Temporal and spatial variation in age-specific net migration in the United States,”

Demography 42: 791-812.

Johnson, Kenneth. 2006. “Demographic Trends in Rural and Small Town America.” Carsey

Institute Reports on Rural America, University of New Hampshire. Available online:

https://scholars.unh.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1004&context=carsey

Oklahoma Department of Commerce. 2017. “1890-2010 Decennial Census Population by

Place by County.” Available online: https://okcommerce.gov/data/demographics/

Sutton, Jonathan. 2014. “Two western Oklahoma towns are among fastest-growing in

U.S.” The Oklahoman. Available online: http://newsok.com/article/3947284

Trotter, Bill. 2011. “Interior Towns Boost Hancock County Population Growth.” BangorDailyNews,

4 May 2011, www.bangordailynews.com/2011/05/04/news/hancock/interior-towns-boost-hancock-county-population-growth/

University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC). 2018. “Rural Health Opportunities Program.” Available online: https://www.unmc.edu/studentservices/rse/enrichment/rural-health-enrichment-programs/rhop/

Welte, C. 2017. “Marketing Hometown America.” Nebraska Institute of Agriculture and

Natural Resources Community Vitality Initiative. Available online: https://communityvitality.unl.edu/marketing-hometown-america-0

Winchester, B. 2009. “Rural migration: The brain gain of the newcomers.” Retrieved

from University of Minnesota Extension website: http://www.extension.umn.edu/Community/brain-gain/

Ryechan Lee

Undergraduate Research Assistant

Brian Whitacre

Professor and Extension Economist

Dave Shideler

Associate Professor and Extension Economist