Understanding Streams

This discussion aims to give landowners the essential information needed to understand how streams work. Further information, including a deeper look at the underlying principles, can be found in the references listed at the end. See the glossary at the end for detailed descriptions of the underlined words.

What Streams Do

Streams have two mechanical functions. The first is to transport water from higher to lower elevations. The second is to transport sediment – earthen materials better known as rock, sand, silt, and clay. In a healthy stream, the amount of sediment being picked up and moved downstream is equal to the amount being deposited in the stream. In unhealthy streams, this balance is lacking; either too much sediment is being deposited or too much erosion is occurring. Excess deposition is usually indicated by the presence of unstable islands or mid-channel sediment bars. Excess channel erosion is indicated by rapid deepening or widening of the channel. Tell-tale signs are high, freshly eroded banks with exposed roots, or deeply incised channels. Both excess deposition and excess erosion may occur in the same channel reach (Figure 1).

Energy

The movement of water and sediment through a stream system involves kinetic energy. The faster the stream flows, the greater the power it has to erode and carry sediment. As children, many of us played with a flowing garden hose to dig holes in the ground, so we have an intuitive understanding of the cutting power of flowing water. Nature provides four ways of keeping this erosive power in check.

The first way streams protect themselves is the growth of deep or densely rooted, water loving plants along the stream channel. This streamside area is known as the riparian zone (Figure 2). These deep and dense root networks hold the riparian soil together. Although this protective zone of vegetation may be damaged from time to time, one of the great benefits of this network of riparian trees, shrubs and grasses is that it is self-repairing. When some plants are lost, others grow in their place.

The second way streams act to dissipate the erosive energy of flowing water is by changing their pattern or meandering (Figure 3). By forming curves the distance the water travels is increased, the slope is decreased, and the water’s velocity slows as a result. It is normal for stream and river channels to slowly move over time. If one could watch a stream from the air over a period of several lifetimes, it would appear as if it were a writhing snake. This is one reason why construction of homes and other structures close to streams should be discouraged.

Figure 3. Over time it is normal for a healthy stream channel to move, or meander. Rivers which carry high sediment loads typically develop a braided pattern of multiple crisscrossing channels, instead of the single channel shown here. (Image credit: Ohio Department of Natural Resources)

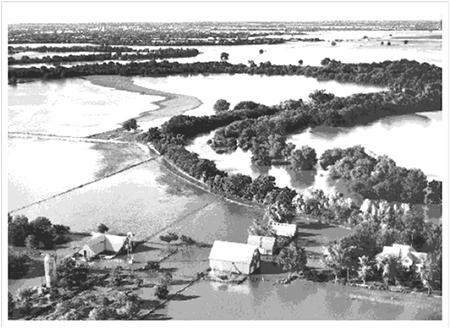

Flooding is the third way in which erosive energy is reduced (Figure 4). During and after rainstorms, the water rises above the streambank and spreads on the floodplain. The velocity of the water outside the channel is very much reduced and, as a result, sediment is deposited. Flooding is a beneficial process as long as people avoid building houses and other structures in the floodplain. Local groundwater tables benefit from the increased infiltration of water, and the deposition of new sediment helps form and maintain productive soils. Flooding is a natural occurrence and is part of normal stream functioning.

Figure 4. It is important to recognize floodplains and understand how they work. See “Further Information” for sources of floodplain maps for your area. Always check a floodplain map before buying or building a home or other structure close to a waterway. (Photo credit: USGS)

The fourth way of lessening the erosive energy of water is the presence of live trees, plants, rocks, or woody debris within the stream channel, particularly the larger streams and rivers. By increasing the resistance to flow, such objects slow the water’s velocity. Down trees, or snags, can also benefit fish populations by creating habitat, such as root wads and scour holes. In smaller streams, down and dead trees may need to be removed to avoid unnecessary flooding. To determine if a logjam or beaver dam should be cleared to maintain flow, seek advice from the Conservation Commission or Department of Wildlife Conservation.

Common Causes of Stream Problems

The failure to understand and respect how nature allows streams to resist erosion can lead to serious problems. While there may be engineering methods for solving these problems, the costs are quite high and almost always beyond the reach of the private landowner. It is far better to understand and respect the ways in which nature regulates stream erosion and avoid such problems (Figure 5).

Figure 5. This high cut bank is the sign of an unhealthy, unraveling stream channel. The channel is being widened as the stream seeks to meander. Once a stream has been degraded this severely, there is little a landowner can do about it. (Photo credit: Mitch Fram)

Along with the benefits of stream ownership, there are some dangers and pitfalls for the uninformed landowner. Whether your stream is a large one that flows year round or a small one that is dry more often than not, take heed of the following warnings:

- Don't “clean up” a stream by clearing off the brush, trees and other deep rooted plants from the banks. Their deep root network is all that holds the creek bank together against the cutting power of the water.

- Do learn to recognize floodplains and don’t build a home or other structure in one. As long as floodplains are left undeveloped, flooding provides the natural benefits of replenishing soil moisture, recharging local water tables, and reducing downstream flooding and erosion.

- Don’t let heavy cattle traffic, vehicles, or equipment damage streambanks. The soils are soft and easily disrupted, setting in motion serious erosion.

- Don’t attempt to straighten a stream channel or cut across a meander. Although the intention may be good, generally it is illegal without a permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. It can seriously damage downstream areas due to increased water velocities and sediment.

- Be aware that stream problems on your land may be the result of upstream problems. If the watershed above your land is eroding, then there will be excess sediment entering your stream. If your channel bed is a rocky one, this sediment can silt in the spaces between the rocks needed by small fish, crawfish, and insects. A different problem occurs when the upstream watershed is covered by buildings, roads, and parking lots. The increased runoff from these impervious surfaces will increase the flow your stream must handle, resulting in deepening or widening of the stream channel.

Streams have an amazing ability to handle the erosive energy of flowing water, but can be made vulnerable to severe damage when a landowner doesn’t appreciate how they work. By the time most stream owners notice a problem, it is usually too late for an affordable solution. Take time to enjoy and understand your stream and do what you can to protect its health.

If you are blessed with a stream, you have something of value that can greatly add to the enjoyment of a property. There is nothing quite like sitting beside a stream and taking in the sights and sounds. Both children and anglers can get a kick out of collecting crawdads, stream insects, and other stream critters. In general, streams with rocky beds and overhanging trees provide the best habitat for fish, but any stream with well vegetated banks and a riparian zone provides a tremendous benefit – they are a durable, self-repairing means of handling high flows that would otherwise erode adjacent land (Figure 6).

Figure 6. This small creek is in healthy condition with a well-vegetated riparian zone. If brush and trees are cleared, bad consequences will follow. Like most Oklahoma streams and rivers, its fate is in the hands of landowners. (Photo Credit: B. Hoagland, Okla. Biological Survey)

Glossary

Channel Bed – The bottom of the stream channel. Streams will usually have rock, sand, or silt channel beds.

Floodplain – The flat area alongside the stream channel that receives floodwaters and sediment when the stream overflows.

Habitat – The specific type of usable space, shelter (cover), food, and water required by a particular animal species. Scour holes created by woody debris and the spaces between rocks in the stream bed are important forms of usable space and shelter for fish and the insects they consume.

Kinetic Energy– The energy produced by motion. Kinetic energy is proportional to the square of velocity. Water flowing at 1 foot per second has only 1/16th of the kinetic energy of water flowing 4 feet per second.

Meander – A bend in a stream or river. Streams naturally form meanders due to erosion and deposition in the stream channel.

Mid-channel Sediment Bar – An unstable island formed by the deposition of sediment. It differs from a point bar, which is attached to an inside bank in a meander curve.

Riparian Zone – The area adjacent to a stream channel that is occupied by water loving trees, shrubs, or other plants. It generally has a greener appearance than surrounding areas.

Sediment – Sand, silt, clay, gravel, or larger rocks that have been moved by water or wind.

Sediment Deposition – The dropping of sediment from suspension whenever velocity decreases to the point that the water no longer has the kinetic energy required to transport the particle.

Silt – Sediment that is larger than clay and smaller than sand.

Snag – A dead tree. These are often valuable as habitat for fish or wildlife.

Watershed – The area of land that catches rainfall and funnels surface water and groundwater to the stream.

Further Information and Resources

- Riparian Area Management Handbook, E-952

- Water Quality Series: Riparian Forest Buffers, NREM-5034

- Riparian Buffer Systems for Oklahoma, BAE-1517

- Ohio Stream Management Website

- North Carolina Stream Restoration Website

Stream Corridor Restoration: Principles, Processes, and Practices by the Federal Interagency Stream Restoration Working Group (FISRWG)(15 Federal agencies of the US government). GPO Item No. 0120-A; SuDocs No. A 57.6/2:EN 3/PT.653. ISBN-0-934213-59-3. Available online at www.nrcs.usda.gov/technical/stream_restoration

https://www.floodsmart.gov/ – The official website of the Federal Flood Insurance Program

http://msc.fema.gov/webapp/wcs/stores/servlet/FemaWelcomeView?storeId=10001&catalogId=10001&langId=-1 – On-line floodplain maps, free

http://www.myfloodzone.com/fema-flood-maps.htm – floodplain maps ($)

Stream Hydrology Models – By flowing water through a bed of plastic grit, these teaching models demonstrate normal stream functioning and then degradation under the influence of bad management practices. Six trailers are available for classroom and public event audiences. Contact your County Extension Service office.

Marley Beem

Assistant Extension Specialist