The Marketing Puzzle

Producers may be bewildered by the number of wheat marketing alternatives. Aggressive marketing economists who discuss each alternative and how complicated they are, add to the confusion. Producers need to view the marketing alternatives as pieces of a puzzle that fit together to form the true market picture (Figure 1).

Puzzle Pieces

The puzzle pieces are Price, Futures Price, Forward Contract, Futures Contract, Basis, Put Option Contract and Call Option Contract (Figure 1). All marketing alternatives are a combination of these seven puzzle pieces. Anyone who understands how each piece fits into the puzzle and impacts price will understand most marketing alternatives.

Figure 1. The Marketing Puzzle

Corner Stone Piece

The corner stone puzzle piece is the cash price (Figure 2). The objective of marketing is to control or influence price. Thus, cash price is the first piece of the puzzle to understand.

Figure 2. Price.

Price, in its simplest form, is the dollar amount received for the commodity sold. Thus, if wheat is sold for $5 per bushel, the cash price is $5. The problem is $5 may not be the amount of money available. The important price is the net price. Net price is a combination of the cash price, costs associated with owning the commodity and profits or losses from other marketing tools.

If a commodity is sold out of storage, the storage costs (carrying costs) must be subtracted from the “price” received. The two types of carrying costs are interest and physical costs. So, if the price of wheat is $5 and the appropriate annual percentage rate is 6 percent, interest cost to carry wheat is 0.0822 cents per bushel per day ($5 x 0.06 ÷ 365), or 2.5 cents per bushel per month ($5 x 0.06 ÷ 12 months).

Storage costs are either on-farm or commercial. On-farm costs vary by the size of facilities, the condition of the commodity in the bin and the level of storage management. Commercial storage is normally a daily fee. A common fee is 0.133 cent per day or 4 cents per bushel per month.

For example, the price of wheat is $5, the appropriate interest rate is 6 percent and the wheat is stored in a commercial elevator with a storage fee of 0.133 cent per day. The carrying costs to store wheat for the 183 days from June 15 to December 15 would be 39 cents per bushel. Interest cost is 0.0822 cents per day or 15 cents total (183 x $0.000822). Storage cost is 24 cents (183 x $0.00133). If wheat is stored until December 15 and sold for $5 per bushel, the net price received would be $4.61 per bushel ($5 minus $0.39 carry).

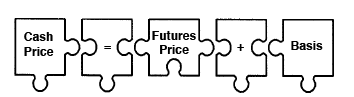

Cash Price Equals Futures Price

Plus Basis

The equation cash price = futures price + basis is the key to the marketing puzzle (Figure 3). Cash price does not change unless either the futures price or basis changes. If the futures price increases 5 cents per bushel, and the basis does not change, the cash price increases 5 cents per bushel. Conversely, if the futures price decreases 5 cents per bushel and the basis does not change, the cash price decreases 5 cents per bushel.

If the futures price changes, either cash price or basis must change. If the basis changes, the cash price or futures price must change. It is possible for the futures price to change and for the basis to change in the opposite direction and there be no change in the cash price. It is impossible for just one of these three puzzle pieces to change.

Another key to understanding the market is to understand how to control the futures price and the basis. By controlling these two puzzle pieces, cash price may be controlled.

Figure 3. Key Marketing Equation.

Forward Contract

A forward contract sets the price (Figure 4). If a forward contract is established at $5 per bushel, the price received for the wheat is $5, regardless of the futures price and the basis. But the equation cash price = futures price + basis still holds. A forward contract is based on a futures contract price and a basis. For example, assume the current date is April 1, the Kansas City Board of Trade (KC) July wheat contract price is $5.30 and the forward contract basis is minus 30 cents. The forward contract price would be $5.

Cash Price = Futures Price + Basis or $5 = $5.30 + (- $0.30)

To protect against price changes, the buyer (elevator) would sell KC July futures contracts for $5.30 (short hedge). When the wheat is delivered against the forward contract, the buyer would take delivery of the wheat and buy the KC contract back. For the buyer, any change in the cash price would be offset by changes in the KC July futures price and the net would be $5. The buyer normally absorbs any loss or gain in the basis.

The point to remember with forward contracts, is for the seller, a futures price and a basis is locked in. Thus, the cash price is fixed at the contracted price. In all cases, the equation holds.

Figure 4. Forward Contract.

Futures Contract

Producers who own the commodity, either in the field or in the bin, may “lock in” a futures price by selling a commodity futures contract (Figure 5). A futures contract requires delivery (acceptance) of a specified commodity at a specific quality and quantity (5,000 bushels for grain), during a specific time period (delivery month), and at a specific location (delivery point). The price of the contract is determined via an electronic auction managed by the Chicago Board of Trade.

Figure 5. Futures Contract.

The futures price is the price of a commodity futures contract. The contract used by the seller will depend on which contract the market is using to determine price. The appropriate contract is normally the next contract scheduled to expire before the delivery month. For example, wheat to be sold in November would use the KC December contract price to determine the cash price. During December, the market would be using the KC March contract.

Assume a producer wants to hedge 20,000 bushels of hard red winter wheat for delivery at harvest (June). Four, 5,000-bushel (KC July) wheat contracts would be sold. If the wheat contracts are sold for $5.30 per bushel, the expected price would be $5.30 plus the basis. If the basis turns out to be a minus 30 cents, the resulting price would be $5 per bushel.

Selling a futures contract works because the cash price = futures price + basis equation must hold. The futures contracts have been sold for $5.30 per bushel, which “locks in” a futures price of $5.30. The futures contract price may not be $5.30 at harvest. But since cash price = futures price + basis, any change in the futures price is offset by an equal change in the cash price. If the futures price increases 20 cents per bushel, the cash price increases 20 cents per bushel (sell KC July at $5.30 — buy back KC July for $5.50). There is a 20 cent loss with the futures contract and a 20 cent gain with the cash wheat. If there is a 20 cent decline in the futures price, there will be a 20 cent decline in the cash price. Thus, the gain in the futures (sell for $5.30 — buy at $5.10) is offset by a 20-cent loss in the cash price.

The difference between forward contracting and hedging is the basis. Forward contracts “lock in” the futures price and the basis. Hedging only “locks in” the futures contract price.

Basis

The basis is the difference between the futures contract price and the local cash price. Both time and location will impact the basis (Figure 6). There are five KC wheat contracts; March, May, July, September and December. For example, the market uses the KC December wheat contract price to set the price of wheat from September through October. Since wheat delivered in October may have a different value than wheat to be delivered in December, the basis is used to adjust the price for the expected difference in market conditions. Even though Kansas City is a wheat delivery point, the price of wheat in a Kansas City elevator is normally different than the underlying KC futures contract price.

An example of basis change for location is when wheat may be worth more in Kansas City than in central Oklahoma. Since the same commodity futures contract is used to deter- mine the price at both locations, grain buyers adjust the futures contract price with the basis. If wheat is worth 30 cents less in central Oklahoma than in Kansas City, the basis for central Oklahoma is set 30 cents less than the Kansas City basis. If the value of wheat in central Oklahoma is the same as in Kansas City, the basis will be the same for both locations. (For additional information read Extension Current Report CR-502).

About the only way to “lock in” a basis is with a forward contract. There are “basis contracts,” but they are rarely used in the Great Plains. When the basis is favorable for producers, it is unfavorable for buyers. Likewise, when the basis is favorable for buyers, it is unfavorable for producers. Basis contracts are used in the Midwest, where the majority of the grain is stored on-farm.

Figure 6. Basis.

Option Contracts

The following put and call option contract discussions pertain to the buyers’ rights and responsibilities. Sellers’ rights and responsibilities will not be discussed. A detailed discussion of put and call option contracts are presented in Extension Fact Sheet AGEC-549, Marketing Puzzle: Futures Option Contracts. Contact the local County Cooperative Extension Agent.

Option contract terms are only important when options are used. Before options are implemented into the marketing plan, the important thing to know is the price impact of buying a put or a call option. Knowing what premium and strike price is will help to understand the following examples. The premium is the cost of the contract. For example, a KC $5.30 July wheat put option contract may cost 40 cents per bushel or $2,000 per 5,000-bushel contract.

The strike price is the “starting point” for establishing the option contract value. A KC July $5.30 put option contract value will depend on whether the KC July wheat contract price is more than or less than the $5.30 strike price.

The buyer chooses the strike price. Each strike has a different value (Premium), which depends on the price level of the underlying futures contract. Don’t get confused with terminology. Concentrate on learning the basic principles. Put option values increase when futures contract prices decrease, and call option values increase as futures contract prices increase. These two principles are the most important to remember about options.

Put Option Contracts

A put option contract impacts price through the futures contract and its price (Figures 1 and 7). It’s important to remember put option contracts’ value increase as the underlying futures contract price declines. Visualize the futures contract and put option contract as two connected tanks of water. If the water level in the futures contract tank declines, the water level in the put option tank increases. If the water level in the futures contract tank increases, the water level in the put option tank declines until the put tank is empty. The put option water level cannot be less than zero.

Figure 7. Put Option Contract.

If a commodity is owned (wheat, corn, cattle, hogs, etc.) and the underlying futures price increases without a change in the basis, the cash price increases, which could be good. If a commodity is owned and the underlying futures price decreases without a change in the basis, the cash price decreases, which could be bad. However, if a put option contract is purchased on the underlying contract, the bad is changed to okay.

Assume wheat is growing in the field, the KC July wheat contract price is $5.30, the expected basis is minus 30 cents, and a $5.30 July put option contract premium (cost) is 40 cents per bushel. Wheat may be hedged or forward contracted for $5 per bushel ($5.30 ‑ $0.30). An alternative to forward contracting or hedging is to buy a $5.30 KC July put option contract. The minimum expected price for buying the put option contract would be $3.60, the $5.30 futures contract price plus the expected basis (-$0.30) and minus the put option premium ($0.40).

Assume the basis at harvest (June) is minus 30 cents per bushel. If the KC July contract is $5.00, the local cash price would be 4.70 ($5.00 – $0.30). If the KC July contract price is $6.50, the local cash price would be $6.20 ($6.50 – $0.30). The equation, cash price = futures price + basis, holds.

Assume a KC July 530 put option contract was purchased for 40 cents per bushel in April. Then, if the KC July contract price is $6.00, the local cash price would be 5.70. The KC 530 July put option contract will have no value, thus the net price would be $5.30 per bushel. This is the $5.70 cash price minus the 40 cent KC July put option premium.

Again, assume a KC 530 July put option contract was purchased for 40 cents per bushel in April. If the KC July contract price is $4.50, the local cash price would be $4.20. The KC 530 July put option contract would be worth at least 80 cents per bushel ($5.30 – $4.50). And the Net price would be $4.60 ($4.20 cash price minus 40 cents premium plus 80 cents final value of the put option).

Call Option Contracts

Call option contracts impact price through the futures contract (Figure 8). As the futures contract price increases, the value of call option contracts increase. As the futures contract price declines, the value of the call option contract declines, until the futures contract price is equal to or less than the call option “strike” price, then the value of the call option is zero.

Figure 8. Call Option Contract.

Since call option contract values move in the same direction as the underlying futures contract price, call option contracts by themselves cannot be used to protect against lower prices. They are used to protect against higher prices and in combination with other marketing tools.

Producers may want to buy call option contracts after the wheat or cattle have been sold. The sale may be through a cash sale (wheat at harvest), after forward contracting (planted wheat or cattle in the feed lot) or after hedging. Cash sales, forward contracts or hedges all lock in the futures price. Cash sales and forward contracts also lock in the basis. Buying a call option captures any futures contract price increase above the call option “strike” price.

Again, assume wheat is growing in the field, the KC July wheat contract price is $5.30, the expected basis is minus 30 cents, and the $5.30 July call option contact premium is 40 cents per bushel. Wheat may be hedged or forward contracted for $5.00 per bushel ($5.30 – $0.30). Forward contracting for $5.00 per bushel locks in both the futures price at $5.30 and the basis at minus 30 cents. After forward contracting, neither a decline nor an increase in the KC July futures contract price will impact the price received. Lower prices do not bother a few producers, however, producers do not like missing the opportunity to receive higher prices. Buying call option contracts after the commodity has been sold allows producers to receive any increase in futures prices.

If wheat is forward contracted for $5.00 per bushel ($5.30 KC July contract price, and -$0.30 basis) and a $5.30 KC July call option contract is bought for 40 cents per bushel, the minimum price would be $4.60 — the $5.00 forward contract price minus the call option premium ($0.40).

Assume a KC 530 July call option contract was purchased for 40 cents per bushel in April. Then, if the KC July contract price is $6.00 when the wheat is delivered in June, the local cash price would be $5.70. However, the wheat would be delivered for the forward contracted $5.00. The KC 530 July call option contract will have a value of 70 cents ($6.00 – $5.30). Thus the price would be $5.30 per bushel, the $5.00 forward contracted price, plus the 70 cent call option value, minus the 40 cent KC July call option premium.

For example, if a KC 530 July call option contract was purchased for 40 cents per bushel in April and was forward contracted for $5.00, when the wheat is delivered in June the KC July contract price is $4.50, the local cash price would be $4.20. The wheat would be delivered for $5.00, the KC 530 July call option contract would not have a value ($5.30 > $4.50 => 0). And the price would be $4.60, $5.00 forward contract price minus 40 cents premium.

Wheat is sold in June for $5.20 per bushel. At the time the wheat is sold, the KC December wheat futures contract price is $5.50 per bushel and a KC $5.50 December call option contract may be bought for 35 cents per bushel. The minimum price received for the wheat will be $.4.85 ($5.20 – $0.35).

However, if the wheat was going to be stored until December 15, storage and interest costs would have been 40 cents per bushel. This would be 5 cents more than the 35 cent cost of the KC $5.50 December call option contract. In effect, carrying costs have been used to pay for the call option contract and any increase in the KC December futures contract price will be captured with the call option contract.

Completed Puzzle

The completed puzzle shows how each marketing alternative impacts price (Figure 1). Since price is the corner stone of the puzzle everything should end with the price impact. The equation, cash price = futures price + basis is key to understanding the puzzle. It must hold for all combinations of alternatives and under all conditions.

The goal of marketing is to use marketing alternatives (tools) to impact price. The following is a short description of each tool:

Forward Contract: It locks in a price by locking in the futures contract price and the basis. The cash price does not change as the underlying futures contract price changes or as the basis changes.

Futures Contract: Any change in the futures contract price changes the cash price in the same direction.

Basis: Any change in the basis changes the cash price in the same direction.

Put Option Contract: This impacts the cash price through a futures contract price. Its value increases as the underlying futures contract price decreases. They are used to protect against lower prices.

Call Option Contract: This impacts the cash price through a futures contract price. Their value increases as the underlying futures contract price increases.

Each of these marketing alternatives should be considered price risk management tools, not price enhancement tools. These tools should be used when managers want to avoid price risk.