Pond Plants: Weeds or Beneficial?

A healthy pond is one that contains a moderate amount of aquatic plants that do not interfere with the use and enjoyment of the pond. It is natural and normal for plants to grow in ponds – trying to totally eliminate them is almost always a mistake. This fact sheet aims to help rural and urban pond owners maintain the right amount and types of plants so they can enjoy a pleasing pond appearance, better fishing and longer pond life.

There are two main types of pond plants. Higher plantshave stems and true leaves.

Higher plants are generally considered beneficial if they occupy around 20% to 30%

of a pond. Algae are a more primitive type of plant without stems or leaves. They

often outcompete higher plants and take over ponds when nutrients run off from lawns,

livestock waste or other fertilizers in the watershed. Microscopic algae

suspended in the water column give pond water a greenish appearance. They are known

as phytoplankton. When a submerged object can be seen at 18 or more inches on a sunny

day, the amount of phytoplankton is considered beneficial. If the phytoplankton are

so dense a submerged object at 12 inches or less cannot be seen, there is a high risk

of an algal die-off with subsequent decomposition causing a low oxygen fish-kill.

See NREM-9223, “Fish Kills” for more details.

The Problem of Overabundance

Any pond plant will cause problems when it is over-abundant. Dense plant growth can interfere with casting and boating access and be unsightly. To maintain a healthy level of plant abundance, do three things:

- If much of the pond is shallow, deepen areas with less than 3 ½ feet of water depth.

This is the depth to which the wavelengths of light useful to plants can penetrate.

Generally, shorelines should have a 3-1 slope: a 1-foot-drop for every three feet

as you move toward the pond’s center. Droughts can be a good time to deepen pond edges.

Large shallow pond edges tend to be filled by

emergent plants such as cattails or bulrush. Shorelines may be too shallow because:

- The pond was built that way.

- Incoming sediment has silted-in areas. Inspect the surrounding watershed area from which runoff fills the pond. If you find actively eroding areas, ask the local office of the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) for advice on erosion control practices.

- Shoreline banks have gradually slumped in through the course of years.

- Heavy cattle traffic has shallowed out the soft, water-saturated banks. Consider restricting cattle access to just one small area (see NREM 2883, “Pond Management for Livestock, Fish and Wildlife”).

- Reduce nutrient runoff into the pond by properly managing fertilizer use in the pond’s watershed. Apply only the amount of chemical fertilizer or animal manure needed, based on soil tests available through the local county Extension office. Consider moving livestock holding areas out of the pond watershed.

- Learn the names of the common plants in the pond and check them often for any becoming overabundant. In addition to this fact sheet, an excellent resource to help in identifying common pond plants and learning more about their management is aquaplant.tamu.edu. Catch weediness problems early and consult the local county Extension educator for advice on herbicides or other management options before it gets out of hand. See NREM-101, “Are Herbicides Safe to Use in My Pond?”

The Problem of Underabundance

A scarcity of higher plants creates problems, including lack of protection against shoreline erosion, limited fish spawning and nursery areas, and inadequate production of insects and other food for fish and other higher animal pond life. Fish, frogs and other higher animal life are an important natural form of mosquito control. Immature mosquitoes live in the water, often hanging at the water’s surface where they are highly vulnerable to being eaten.

There are three common situations associated with too few higher plants:

- Newly constructed ponds where not enough time has passed for higher plants to establish themselves.

- Muddy ponds. This condition prevents light penetration thereby inhibiting plant growth. See the corrective steps in NREM 9206 – Common Pond Problems.

- Ponds where herbicides have been used to remove all or most higher plants. Typically this leads to excess growth of algae.

Benefits of Aquatic Plants

Aquatic plants are an essential part of a healthy pond ecosystem. Two categories stand out for their particular benefits:

Submerged plant beds provide:

- Insects for smaller fish.

- Spawning areas and refuge for smaller fish from large bass.

- Areas for anglers and bass to find fish.

- Utilization of nutrients and shading of the water column to help prevent nuisance algal blooms.

- Food for certain waterfowl is provided by various aquatic plant species e.g. southern naiad.

- Oxygen production through photosynthesis – submerged plants and microscopic algae are the major oxygen producers in ponds. Dissolved oxygen is essential for fish survival and growth and can be scarce at times.

Shoreline emergent plants provide:

- Prevention of wave erosion – especially important on larger wind-swept ponds.

- Wildlife nesting and breeding habitat.

- Natural beauty to soften the transition from water to land.

Adding Plants to a Pond

Successful plant management can improve fishing and pond performance as well as prevent shoreline and dam erosion. Before introducing new plants to the pond, there are some cautions to consider. Any plant can become overabundant if the conditions are favorable for unrestricted growth. Plants usually expand their area of coverage until they run out of resources. Those recommended in this fact sheet may just do so more slowly than others.

It may be better to simply manage the plants you already have and skip the effort of adding new ones. Here are some of the possible problems that may be encountered when adding new plants to a pond:

- There is no guarantee a particular plant will do well in your pond. The specific requirements of aquatic plant species, such as preferred soil type, pH and other factors are often unknown.

- Deer or other wildlife may eat the transplanted plants. It may be necessary to protect them with cages to allow the plant to survive, reproduce and spread.

- Plants tend to keep growing and expanding when they are in a suitable environment, such as a pond with a large amount of shallow areas. Even “non-weedy” species may become more abundant than you wish.

- Non-native plant species should not be planted in ponds or other outdoor settings – they can spread uncontrollably.

How to Obtain Plants

There are three ways to obtain new plants:

- Purchase from a knowledgeable aquatic plant nursery.

- Purchase from a store that may have little knowledge of what they are selling.

- Collect desirable plants growing in another pond. Hold them in a nursery setting, then transplant into the target pond.

Be cautious about purchasing aquatic plants. Many of the qualities making plants desirable as water garden or aquaria species (e.g. hardy, fast growing, suited to a wide range of conditions) also make them serious potential weed species that should not be planted in ponds.

It is best to transplant plants collected from the wild into a nursery. Plant material can be put into soil-filled containers placed in shallow, inexpensive pools such as a small kiddie swimming pool. Stem fragments, daughter plants, root crowns, tubers, winterbuds and even seeds can be used, depending on the plant species. Established in containers will allow an increase the survival rate and observe for any undesirable plants have “hitchhiked.” If hitchhikers do grow in the nursery containers, it is best to replant into other containers until they are no longer present.

Use a fine textured soil with from 10% to 20% organic matter. Do not use sandy soil

because nutrients will readily leach out into the water and cause problems with algal

growth. Fill the bottom quarter of the container with soil, add the appropriate type

and amount of fertilizer, then fill with soil until the container is four-fifths full.

For submersed plants, use ammonium sulfate (21% N) at rates of 2.5 grams per 4-inch

pot or 10 grams per 6-inch pot (0.5 grams N/L of medium). Use only ammonium salts

and do not use nitrate or urea. For floating leaved and emergent plants, use fertilizers containing

N-P-K (nitrogen-phosphorus-potassium) ratios such as 15-5-5 (or similar) with micronutrients

instead of N alone. Fertilizer rates should not exceed 1 gram N/L substrate to prevent

damage to roots.

If using water from municipal or rural water systems, dechlorinate it first.

Take care to identify plants properly. If plants are misidentified when collecting them for transfer an undesirable plant may be unintentionally introduced. See the list of undesirable species toward the end of this publication.

What Plants Might I Consider Adding?

Here are some common native aquatic species which generally do not get out of hand in ponds. The planting guidelines given are from “Water Plants for Missouri Ponds” and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers publication ERDC/EL TR-13-9, “Propagation and Establishment of Native Plants for Vegetative Restoration of Aquatic Ecosystems.”

Winterbuds

In addition to transplanting and the direct sowing of seed, some aquatic plants can be introduced directly or reared in a nursery using their “winterbuds.” These are compacted vegetative buds produced along the stem that overwinter and form a new plant. They are sometimes called “turions.”

Figure 1. Winterbuds of bladderwort

Credit: By Kenraiz Krzysztof Ziarnek (Own work) [GFDL or CC]

BY-SA3.0 ], via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 2. Winterbuds of milfoil

1 [GFDL -SA-3.0 15:07, myself) CC-BYFabelfroh --Peters (photographed by Kristian (UTC) By 2006 or Credit: January ], viaWikimedia Commons

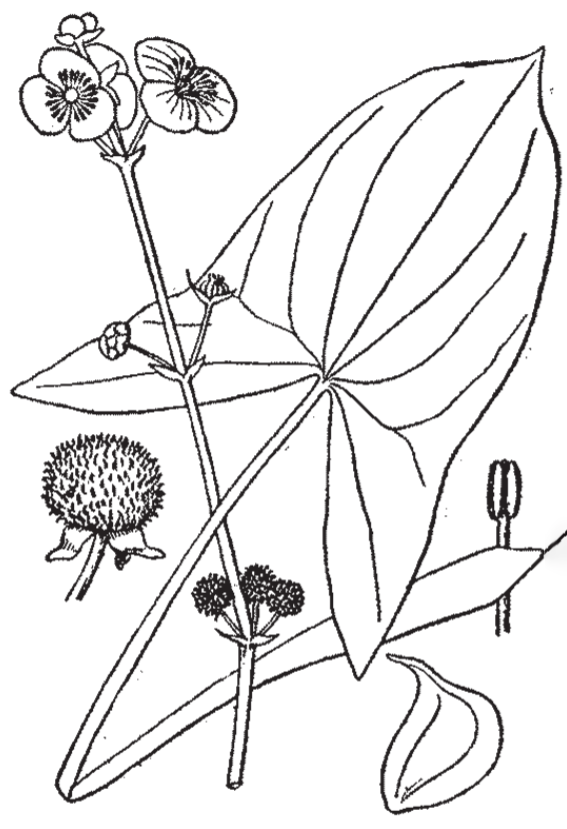

Arrowheads (Sagittaria spp.)

Sagittaria grow in shallow water and shoreline areas. Some species have an arrowhead-shaped leaf while others have a more spear-shaped leaf. They are used as food by a variety of wildlife, making them both beneficial and vulnerable. Broadcast the seeds in fall or spring, or set out plants or tubers from March 1 to August 1.

Figure 3. Arrowheads (Sagittaria spp.)

Credit: USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database

Figure 4. Arrowheads (Sagittaria spp.)

Credit: Aquaplant

Figure 5. Illustration of Arrowheads (Sagittaria spp.)

Credit: USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database

Spike rush (Eleocharis spp.)

Spike rush live in water-saturated soils along the water’s edge. There are many different species ranging in height from a few inches to 2 feet. Planting can be done from April to August. Space plants about 1 foot to 3 feet apart in moist areas.

Figure 6. Spike Rush (Eleocharis spp.)

Credit: Aquaplant

Figure 7. Spike Rush (Eleocharis spp.)

Credit: USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database

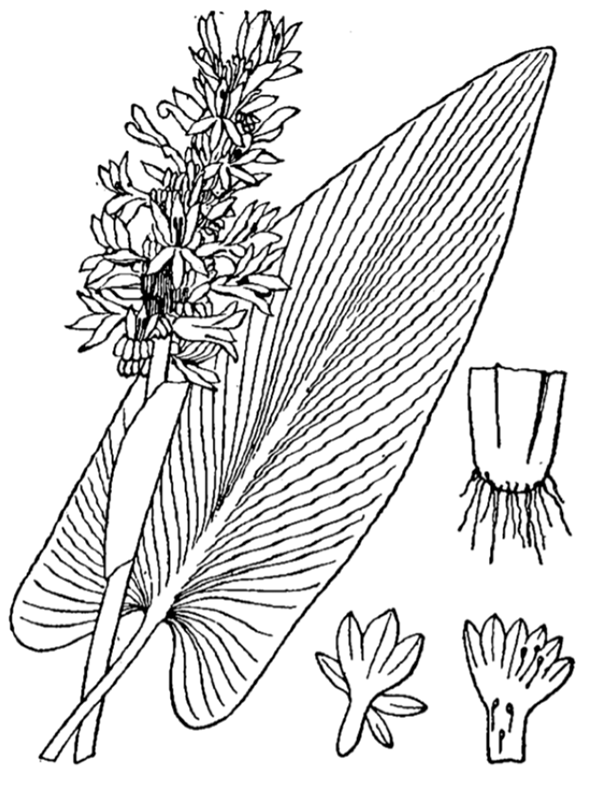

Pickerelweed (Pontedaria cordata)

Look for glossy green leaves that are heart or lance shaped. Showy violet-blue flowers are arranged in spikes. Plant pickerelweed roots in the spring in a sunny spot with rich bottom mud. Commonly used in water gardens.

Figure 7. Pickerelweed (Pontedaria cordata)

Credit: USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database

Figure 8. Illustration of Pickerelweed (Pontedaria cordata)

Credit: USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database

American pondweed (Potamogeton nodosus)

This plant is desirable for fish habitat and waterfowl food. It can be directly transplanted as winterbuds or cuttings from the growing tips can be planted in containers in an aquatic plant nursery bed as previously described.

Figure 9.1 American Pondweed (Potamogeton nodosus)

Credit: Aquaplant

Figure 9.2. American Pondweed (Potamogeton nodosus)

Credit: Aquaplant

Illinois pondweed (Potamogeton illinoensis)

This plant has a combination of floating and submerged leaves creating a potentially good fish habitat. Both of these pondweeds are less likely to overshade the pond than some other species of Potamotegon. Because of the potential for confusion with other species, it may be best not to transplant unknown Potatogeton species. The veins within the leaves are parallel on all of the Potamogetons.

Specific planting instructions are not available for introducing Illinois pondweed but the recommendation for longleaf pondweed might apply: Transplant either winterbuds or nursery grown transplants in early spring. Plant three to five winterbuds together in a cotton bag. Transplanting can be done up until midsummer. Recommended water depth is 50 cm to 100 cm (20 inches to 40 inches).

Figure 10. Illinois Pondweed (Potamogeton Illinoensis)

Credit Aquaplant

Figure 11. Illinois Pondweed (Potamogeton Illinoensis)

Credit: Aquaplant

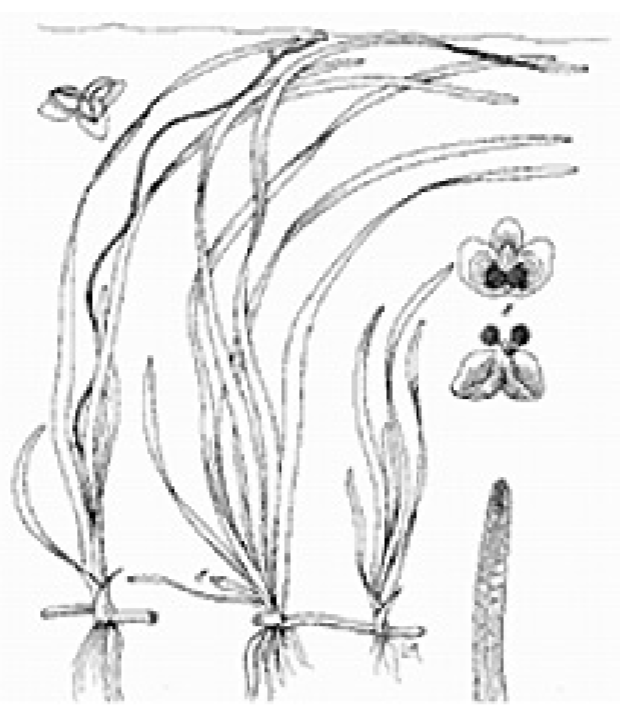

Eelgrass (Vallisneria americana)

This submerged plant is also known as tapegrass or wildcelery. Plants or rootstock can be set out in water a foot or more deep from early spring to early fall at a water depth of from 50 cm to 100 cm (1 1/2 feet to 3 feet). Transplants must be planted deep enough to cover the root mass and anchor the plant, but care must be taken not to bury the basal rosette. Eelgrass is eagerly eaten by turtles and waterfowl.

Figure 12. Illustration of Eelgrass (Vallisneria americana)

Credit: USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database

Figure 13. Eelgrass (Vallisneria americana)

Credit: Aquaplant

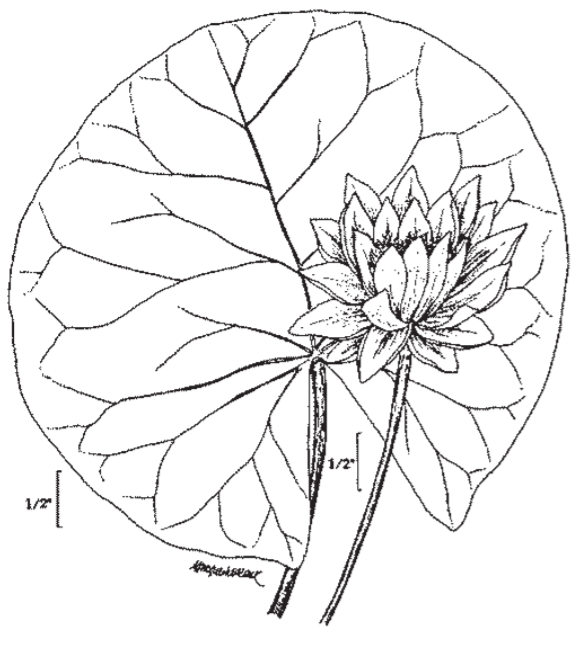

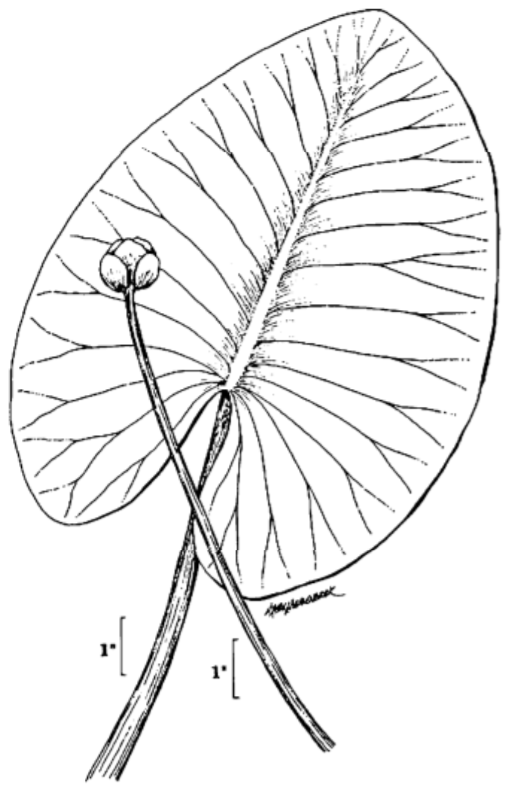

Spatterdock (Nuphar luteum)

Spatterdock can be a useful addition for improving habitat in fishing ponds and lakes. It is commonly mistaken for water lilies. The leaves are heart-shaped. Their flowers are smaller than lilies, not at all “showy” and do not appear to open. Spatterdock is able to grow in clear or turbid water and in sunny or shaded spots, but requires sunny conditions to develop the small blooms.

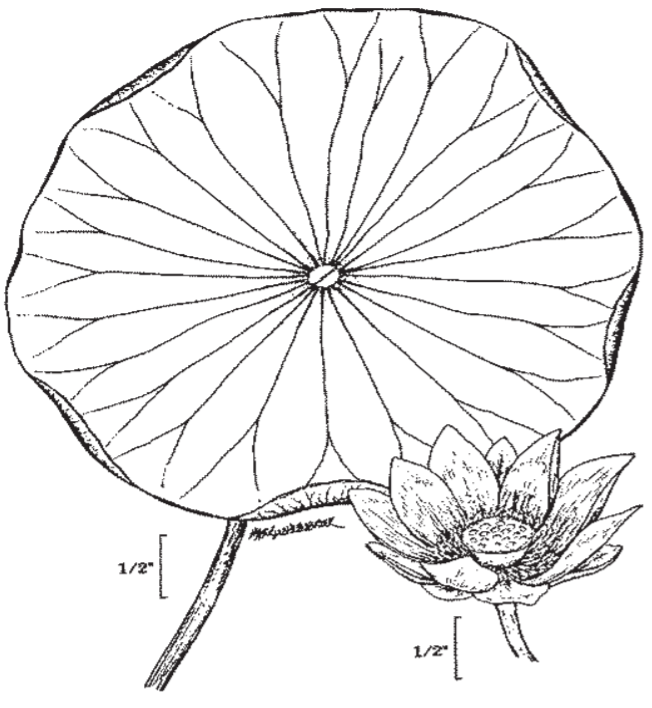

Spatterdock is often confused with water lilies. Note that water lily leaves (below) are circular and have a slit. Spadderdock may also be confused with the undesirable plant American lotus (page 8).

Figure 14. Illustration of Spatterdock (Nuphar luteum)

Credit: USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database

Figure 15. Spatterdock (Nuphar luteum)

Credit: Aquaplant

Water lily (Nymphaea spp.)

Figure 16. Illustration of Water Lily (Nymphaea spp.)

Credit: USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database

Figure 17. Water Lily (Nymphaea spp.)

Credit: Aquaplant

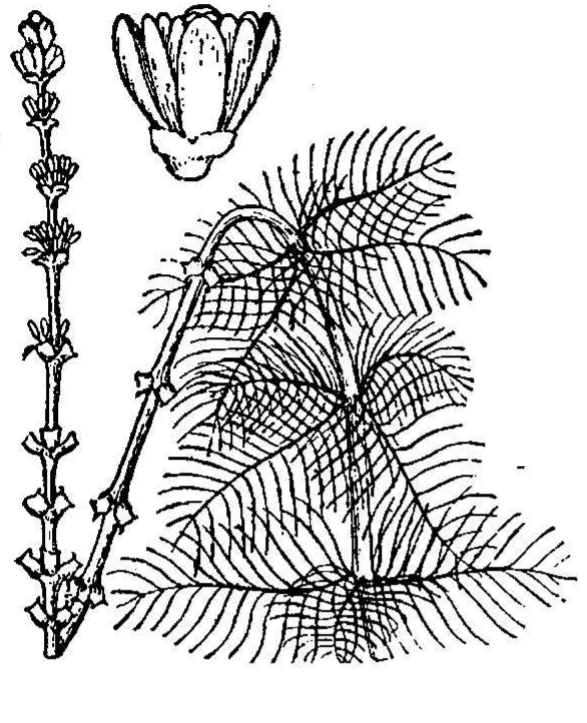

Smartweed (Polygonum hydropiperoides)

This shallow water, shoreline plant has small pinkish flowers. Stems are jointed. May be cultivated from seeds or rooted stems. Smart weed seeds are food for many waterfowl and songbird species.

Figure 18. Illustration of Smartweed (Polygonum hydropiperoides)

Credit: USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database

Figure 19. Smartweed (Polygonum hydropiperoides)

Credit: USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database

Water willow (Justicia americana)

This shoreline plant can be beneficial in larger ponds but is not recommended for smaller ponds, since it usually fills all shallow areas. Leaves are arranged opposite from each other. The small flowers are among the most beautiful of any of our native aquatic plants. It is usually found in ponds only when introduced. It can be planted in 6 inches to 10 inches of water between April 1 and October 20. On larger areas where individual planting is impractical or wave action is a problem, uprooted plants can be simply scattered and chickenwire used to hold them in place until they root.

Figure 20. Illustration of Water Willow (Justicia americana)

Credit: USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database

Figure 21. Water Willow (Justicia americana)

Credit: USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database

Figure 22. The small but beautiful flower of water willow.

Credit: Dan Tenaglia

What Plants May Be Undesirable?

The following plants are frequently reported to cause problems in Oklahoma ponds. But do not panic if these plants are already in the pond. They do not always become overabundant. Most can be part of a healthy balanced pond plant community. Monitor their abundance to see if they are increasing and in need of management.

Eurasian Milfoil – Undesirable

This harmful exotic plant was introduced to the U.S. by the aquarium industry. Much damage has been done to aquatic ecosystems by this and other exotics. Do not transplant any milfoil species.

Figure 23. Eurasian Milfoil

Credit: Aquaplant

Figure 24. Illustration of Eurasian Milfoil

Credit: USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database

American Lotus – Undesirable

This plant is sometimes added to ponds because of its beautiful yellow flower. Unfortunately, it aggressively fills shallow areas making for unattractive conditions. American lotus can be identified separately from water lilies and similar plants because it does not have a slit in its large circular leaf, and it has a distinctive conical seedpod resembling a showerhead. It is not recommended for transplanting except in large water bodies with a limited amount of shallow area.

Figure 25. American Lotus

Credit: Aquaplant

Figure 26. Illustration of American Lotus

Credit: USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database

Southern Naiad – Often Undesirable

This soft, submerged plant often fills up new ponds. By looking closely, it is easy to distinguish from filamentous algae (a.k.a. “pond moss”). It has stems and long narrow linear leaves. It provides food for waterfowl.

Figure 27. Southern Naiad

Credit: Aquaplant

Figure 28. Southern Naiad

Credit: Aquaplant

Creeping Water Primrose – Often Undesirable

Many pond owners dislike the looks of this pond edge plant, fearing it will cover their pond entirely. It almost never does and is instead limited to a 12- to 15-foot wide band around the pond. Primrose is rooted at the shore, producing a floating “vine” which grows toward the middle of the pond.

Figure 29. Creeping Water Primrose

Credit: Aquaplant

Figure 30. Creeping Water Primrose

Credit: Aquaplant

Chara – Often Undesirable

Surprisingly, this submerged plant is an alga rather than a higher plant. A distinct musky-garlic smell is a feature of this plant.

Figure 31. Chara

Credit: Aquaplant

Figure 32. Chara

Credit: Aquaplant

Coontail – Potentially Undesirable

Look for the tiny projections on the outer edge of whorled leaflets. They give this soft submerged plant a somewhat prickly feel.

Figure 33. Coontail

Credit: Aquaplant

Figure 34. Coontail

Credit: Aquaplant

Cattails – Potentially Undesirable

This is a native plant that can be beneficial in moderate amounts but commonly takes over shallow pond areas. The blowing cottony seeds of this plant allow it to easily spread to new ponds. It can fill shallow shorelines, sometimes entirely blocking the water view.

Figure 35. Cattail

Credit: Aquaplant

Bulrush – Potentially Undesirable

Like cattails, this tall emergent plant can take over shallow shorelines. A large, drooping seed head is found close to the top of the plant.

Figure 36. Bulrush

Credit: Aquaplant

Figure 37. Bulrush

Credit: Aquaplant

Purple loosestrife – Undesirable

Figure 38. Purple Loosestrife

Credit: Eric Coombs

Figure 39. Purple Loosestrife

Credit: Eric Coombs

Water Garden and Aquaria Plants

Plants used in water gardens and aquaria should be kept out of ponds, streams and other natural bodies. Never allow them to be deliberately or accidentally released into ponds or other wild settings and you will not have to worry about potential damage to aquatic ecosystems.

Water lettuce – Undesirable

Figure 40. Water Lettuce

Credit: Forest and Kim Starr

Water hyacinth – Undesirable

Figure 41. Water Hyacinth

Credit: Aquaplant

Figure 42. Water Hyacinth

Credit: Aquaplant

Brazilian Waterweed – Undesirable

Figure 43. Brazilian Waterweed

Credit: Robert Videki

Hydrilla – Undesirable

Figure 44. Hydrilla

Credit: David J Moorhead

Figure 45. Hydrilla

Credit: Robert Videki

Parrotfeather Watermilfoil – Undesirable

Figure 46. Parrotfeather Watermilfoil

Credit: Leslie J Mehrhoff

Waterclover – Undesirable

Figure 47. Waterclover

Credit: Graves Lovell

Yellow Iris – Undesirable

Figure 48. Yellow Iris

The Overall Picture

Before deciding to add plants to a pond, please review the cautions and warnings above. Many aquatic plants have the potential to become weeds with the right circumstances.

A diverse pond plant community is generally desirable – the different plant species compete against each other for light, nutrients and space – helping prevent any single plant species from becoming overabundant. The overabundance of one plant may or may not be temporary. In new ponds, predominance by one species sometimes lasts for several years until other species can grow enough. In addition, disturbances like droughts and overuse of aquatic herbicides tend to destabilize diverse plant communities, leading to problems.

In managing ponds and their plants, aim for balance by:

- Designing or modifying the pond basin to minimize shallow areas and by preventing the shallowing out of pond edges by livestock traffic. This helps ensure emerging plants do not become overabundant.

- Managing the watershed to limit the amount of phosphorous fertilizer (the middle initial in the N-P-K listed on fertilizer bags) that runs off into the pond. This helps ensure algae or higher plants do not become overabundant. Work with the local county Extension educator to get good soil tests done whether for around the home or for agricultural fields. Determine the amount of fertilizer needed – apply only that amount and do so only when plants are actively growing.

- Being patient in working to promote plant diversity and allowing years for changes to occur. This promotes balance.

Transplanting aquatic plants to achieve a balanced healthy plant community in the pond may or may not be necessary. Simply managing the naturally occurring species already present may be more desirable.

More information about pond management is available from the Extension Pond Management Homepage.