On-Farm Ethanol Production Regulatory Guide

- Jump To:

- Introduction

- Assumptions Made in this Guide

- Fuel Alcohol Production Facility Registration

- Department of Treasury’s Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) Registration

- IRS Registration

- EPA Registration

- OTC Registration

- ODAFF Registration

- Tax and Incentive Issues

- Income Tax Issues

- Renewable Fuels Standard (RFS)

- Environmental Permitting

- Air Permitting

- Water Issues

- Waste

- Tank Storage Issues

- Community Right-To-Know Issues

- Employee Safety

- Boilers

- Hazard Communication

- Building and Zoning Restrictions

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1

- Appendix 2

- Appendix 3

Note: This publication is intended to provide general information about legal issues. It should not be cited or relied upon as legal authority. State laws vary and no attempt is made to discuss laws of states other than Oklahoma. For advice about how these issues might apply to your individual situation, please consult an attorney.

Introduction

More and more agricultural producers are not only being asked to produce the world’s food and fiber; but also the world’s fuel. Recent years have seen tremendous increases in the amount of biofuels, such as ethanol and biodiesel, that are being produced from agricultural sources such as corn, sorghum and oilseed crops. Agricultural producers themselves have shown increasing interest in adapting the technologies used on an industrial scale to produce the fuels to the farm level and fuels for their own use. While on-farm production of biofuels can help producers in managing fuel price risk and provide them with another use for their crops, the production of fuels also triggers many regulatory requirements. Many of these regulations do not carry exemptions for small-scale production of fuels, and, as a result, those who produce fuel simply for their own use may often face the same regulations as a large, commercial refinery.

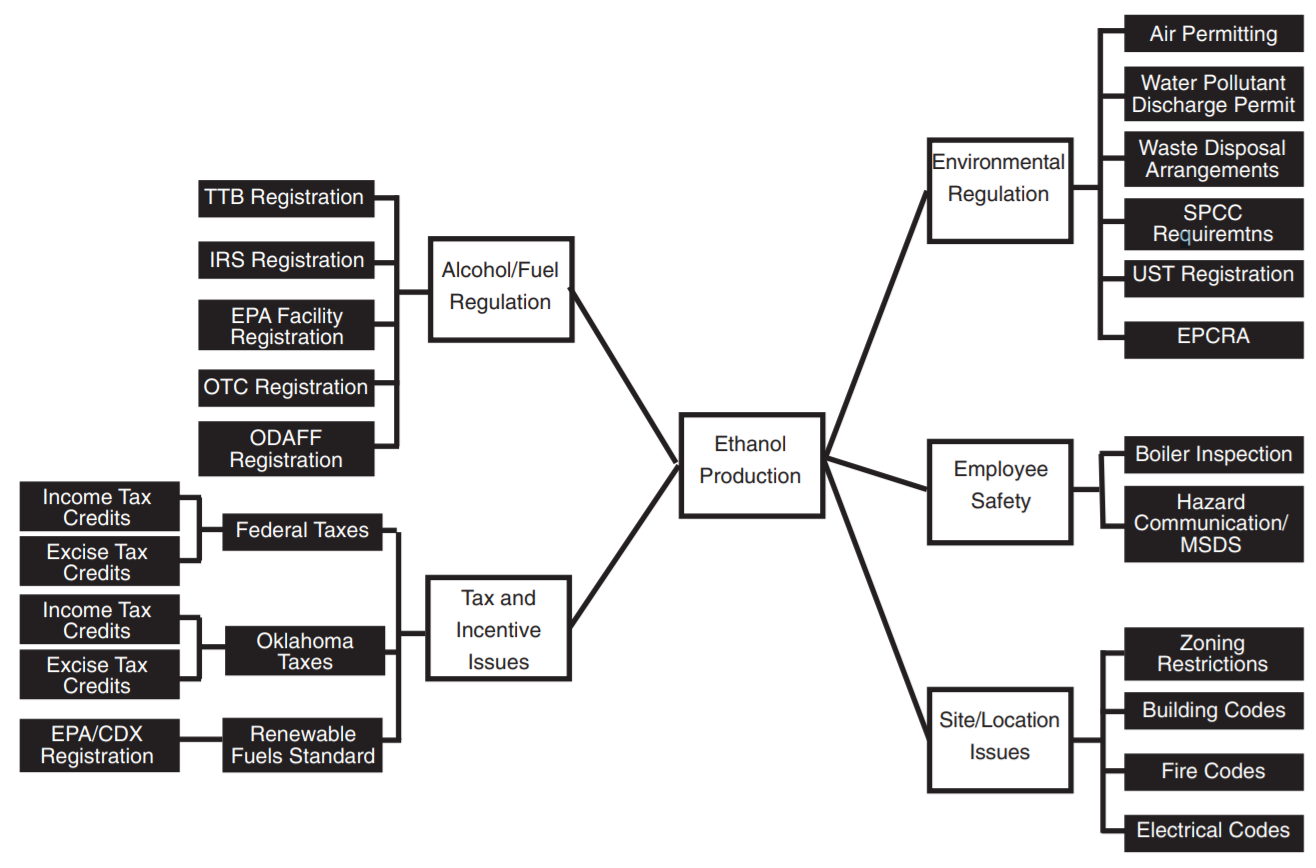

Figure 1. Issue Map for On-Farm Ethanol Production.

Assumptions Made in this Guide

This guide will present a number of the regulations that may apply to the on-farm production of ethanol and is targeted to readers who are considering producing fuel primarily for their own use and not for sale to others. It is assumed that the reader will be producing less than 5,000 gallons of pure ethanol.1

It is also assumed that all fuel produced is used for “off-road” purposes and is not used in any vehicle for highway travel. The use of any ethanol produced in any vehicle for highway travel would trigger the application of a host of additional fuel regulations at both the state and federal level. Please also note that this guide will focus solely on the regulations that govern the production of fuel. It will not address issues such as liability for injuries on the premises where the fuel is produced or damage to vehicles in which the fuel is used, nor will it discuss legal structures for the entity producing the fuels (such as organizing a corporation, limited liability company or cooperative for the fuel production).

Finally, it is important for the reader to consult with the agencies listed, as well as any county or municipal governments, to be sure all requirements have been satisfied. Always consult with a licensed attorney with experience in your type of issue should legal concerns arise.

1 That is to say, 5,000 gallons of 200-proof alcohol [before the addition of any denaturant, or 5,100 gallons of ethanol after the addition of denaturant] per year, which would equate to 10,000 “proof-gallons” of alcohol per year. “Proof-gallons” is not a frequently used unit, but it does appear in several regulations governing alcohol production.

Fuel Alcohol Production Facility Registration

The mere production of ethanol triggers the jurisdiction of a number of agencies at both the federal and state level. At the federal level, the Department of the Treasury and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) all require the registration of any alcohol production facility. At the state level, the Oklahoma Department of Agriculture, Food and Forestry (ODAFF) and the Oklahoma Tax Commission (OTC) also require facility registration. Each of these registrations will be addressed in turn.

Department of Treasury’s Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) Registration

Under the Internal Revenue Code, the Department of the Treasury has the authority to require the registration of any facility used for “producing, processing and storing, and…using or distributing distilled spirits to be used exclusively for fuel use.”2 Distilled spirits, as used in this requirement includes ethanol.3 Thus, producers of ethanol fuel must complete the Form TTB F 5110.74.

As specified in the instructions to the application, the alcohol production facility must be set up prior to completing the application so an accurate diagram of the facility can be included with the application. On the other hand, TTB regulations also prohibit the operation of the facility until after a permit has been issued.

As a result, the applicant should use great care to make sure the application is complete and correct to minimize the amount of time he or she must wait to receive the permit and begin operating the facility.

To obtain a TTB permit, the applicant must show that they will meet the requirements for construction of the facility and its security, which includes requirements that the facility be secured against theft of the fuel.5 Facilities must also use approved gauging devices for measuring and reporting fuel production (such fuel production must be reported on an annual basis after the permit is issued).6

Another requirement to secure TTB approval of the facility is posting a bond with the TTB to cover potential regulatory expenses or regulatory liabilities if the facility produces more than 10,000 “proof gallons” of alcohol per year.7 A proof gallon is defined in the regulations as:

a gallon of liquid at 60 degrees Fahrenheit which contains 50 percent by volume of ethyl alcohol having a specific gravity of 0.7939 at 60 degrees Fahrenheit referred to water at 60 degrees Fahrenheit as unity, or the alcoholic equivalent thereof.8

Put another way, one (1) gallon of pure ethanol (which would be 200 proof) would equal two (2) proof-gallons. Thus, if a facility produces less than 5,000 gallons of pure ethanol (or 10,000 proof-gallons), no bond is required to obtain the TTB permit.9

A final requirement for the TTB permit is that the producer has to “denature” the fuel produced at their facility. Denaturing means making the ethanol unfit for beverage use through mixing with a substance that cannot be consumed by humans.10 Denaturants must be mixed at a ratio of two (2) gallons or more of denaturant to each 100 gallons of ethanol.11 Approved denaturants include gasoline, kerosene, deodorized kerosene, rubber hydrocarbon solvent, methyl isobutyl ketone, nitropropane isomers, heptane, or any combination of these denaturants.12 There is some discretion for the applicable TTB officer to approve alternative denaturants, such as engine lubricants, but you must secure approval for such denaturants.13 The most common denaturant is low-grade gasoline, often called drip gas.14

2 26 U.S.C. § 5181.

3 See 27 C.F.R. § 19.907.

4 See 27 C.F.R. § 19.910.

5 27 C.F.R. §§ 19.965-19.966.

6 27 C.F.R. §§ 19.965-19.966.

7 27 C.F.R. § 19.957.

8 27 C.F.R. § 19.907.

9 26 U.S.C. § 5181(c)(3)-(4).

10 26 U.S.C. §§ 5181(e)(2), 5214(a)(12)

11 27 C.F.R. § 19.1005.

12 27 C.F.R. § 19.1005.

13 Id.

14 Drip gas is listed as an authorized denaturant under the authority of the TTB pursuant to 27 C.F.R. § 19.1005(b). For more information, see the list of Authorized Materials for Fuel Alcohol.

IRS Registration

Regardless of whether the ethanol produced by a facility is used on-road or off-road, or even as heating fuel or fuel for the generation of electricity, the biodiesel facility is required to register with IRS for the purpose of fuel excise taxes.15 To register, use IRS form 637, “Application for Registration” (for certain excise tax activities). For additional information about excise tax issues, consult IRS Publication 510, “Excise Taxes”. Excise taxes are discussed in greater detail below.

15 26 U.S.C. § 4101

EPA Registration

EPA requires the manufacturer of any “designated” fuel or fuel additive to register the fuel.16 Gasoline, and any additive used in gasoline, are among the designated fuels and fuel additives.17 Since many producers will mix gasoline with ethanol for use as a fuel (even if the gasoline is used only as a denaturant), it may be necessary to register an ethanol production facility and its fuel with EPA.18 Facility registration is accomplished using EPA Form 3520-20A. While registration of the facility is relatively easy, registering a fuel additive such as ethanol can be more complex. Fuel additive registration will require not only submission of the registration form19 (EPA Form 3520-13) but will also require the submission of data regarding the environmental and health impacts of the fuel.20 This data can be extremely time-consuming and expensive to compile; however, EPA has allowed industry groups to work collectively to prepare this data.21 If an individual producer can show they have been authorized by one of these groups, they may submit the group data as if it were their own. For more information on obtaining this data, contact the Renewable Fuels Association or by calling (202) 289-3835.

EPA’s facility and fuel registration requirements are targeted at facilities that produce fuel for sale, and thus the applicability of these regulations for application to a facility that produces ethanol strictly for on-farm use is not clear. As a result, the reader should consider contacting the EPA Fuels and Fuel Additives program office for assistance in determining the applicability of these regulations to their specific operation. This office can be reached at 202-343-9027.

16 40 C.F.R. § 79.4(a)(1), (b).

17 Gasoline for use in motor vehicles is designated pursuant to 40 C.F.R. § 79.32. Although ethanol is not explicitly designated, if it is blended with gasoline to produce a motor vehicle fuel, it is also designated pursuant to 40 C.F.R. § 79.31.

18 Fuel additive is defined as “any substance, other than one composed solely of carbon and/or hydrogen, that is intentionally added to a fuel named in the designation…and that is not intentionally removed prior to sale or use.” 40 C.F.R. § 79.2(e).

19 40 C.F.R. § 79.20.

20 40 C.F.R. § 79.23(a), 40 C.F.R 79 Part F.

21 40 C.F.R. § 79.56(a).

OTC Registration

The statutes governing Oklahoma’s excise taxes for motor vehicle fuels defines blended fuel to include ethanol and does not distinguish between on-road and off-road uses.22 Given this, an ethanol producer may need to register as a “supplier”23 of ethanol fuel pursuant to OTC regulations for entities that may have to collect excise taxes.24 For help in determining whether a supplier registration is needed for your operation, contact the OTC at (405) 522-5658 or via email at otcmaser@tax.ok.gov.

22 68 Okla. Stat. § 500.3(421) defines motor fuel as “gasoline, diesel fuel and blended fuel.” 68 Okla. Stat. § 500.3(6) in turn defines “blended fuel” as “a mixture composed of gasoline or diesel fuel and another liquid, other than a de minimis amount of a product such as carburetor detergent or oxidation inhibitor, that can be used as a fuel in a highway vehicle. This term includes gasohol, ethanol and fuel grade ethanol.” Denatured ethanol would satisfy this definition. Note that if the fuel is fit for use in a highway vehicle, it satisfies the definition, even if it is not in fact used for highway travel.

23 See 68 Okla. Stat. § 500.3(56), defining “supplier.”

24 Okla. Admin. Code § 710:55-4-100.

ODAFF Registration

The ODAFF requires an operating permit for any facility that “engages in the production of alcohol for use as a motor fuel.”25 To obtain the permit, the fuel producer must complete ODAFF Form EA-1(a). The permit application will ask for information regarding the ownership of the plant (i.e. as a sole proprietor, corporation, etc.), the type of distillation equipment used, the type of feedstock used for the fermentation process (grains, sugar based crops, fruits, etc.), a diagram of the plant, and a copy of your federal TTB permit. The permit carries a fee of $25.00, and must be renewed annually for the same fee. The permit must be prominently displayed at the production facility.26

This permit is required pursuant to the Oklahoma Fuel Alcohol Act and its associated regulations.27 The requirements of these rules are largely the same as those of the federal Department of Treasury rules.28 The most notable exception is an alcohol production facility that receives and stores grain and does not pay for the grain upon delivery must also be chartered as a public commodity storage warehouse under the Oklahoma Public Warehouse and Commodity Storage Indemnity Act.29 If you will be receiving grain from other producers and using it in addition to your own for biofuels production, you should consider the impact of this requirement.

25 2 Okla. Stat. § 11-21.

26 2 Okla. Stat. § 11-23.

27 2 Okla. Stat. §§ 11-20 through 11-27, and Okla. Admin. Code §§ 35:13-1-1 through 35:13-1-5.

28 See Okla. Admin. Code § 35:13-1-1.

29 Okla. Admin. Code § 35:13-1-4.

Tax and Incentive Issues

At the federal level, three important incentive programs are targeted at biofuels production: income tax credits, excise tax credits, and programs under the Federal Renewable Fuels Standard. Each program takes a slightly different approach to encouraging biofuels development.

Important note: While many of the regulations affecting ethanol production are complex, those governing ethanol taxation and tax credits are even more so. Consult with a qualified tax expert for assistance in determining your tax liability and tax credit eligibility.

Income Tax Issues

While there are several income tax credits available for biofuels production, most of them are conditioned on the sale of the biofuels to another party. To take full advantage of these credits for fuels used on the producer’s own operation, the producer may need to restructure their operation and place ethanol production into a separate legal entity, such as an LLC or corporation, that can then sell the fuel to the farming operation. As always, consult the appropriate tax and legal experts for more information.

Income tax credits for ethanol producers consist of three components. 26 U.S.C. § 40 provides an “alcohol fuels credit” that consists of an alcohol mixture credit, an alcohol credit, and a small ethanol producer credit. The alcohol mixture credit provides a credit of $0.60 per gallon of alcohol used by a facility in producing a qualified mixture (a mixture of alcohol and gasoline sold by the facility for use as a fuel). The alcohol credit also provides a credit of $0.60 per gallon of alcohol (if the alcohol is not mixed with anything but a denaturant) sold by the alcohol producer “at retail to a person [using the alcohol as fuel] and placed in the fuel tank of such person’s vehicle.” In other words, the alcohol credit applies to facilities that both produce alcohol fuel and sell it directly to customers at retail. Thus, given the assumptions set forth at the beginning of this guide, this credit will likely not be available to the reader. Lastly, the small producer credit, also called the Small Ethanol Producer Tax Credit (SEPTC) allows a credit of $0.10 per gallon of qualified ethanol fuel production to producers whose facilities have a productive capacity of 60 million gallons per year or less. “Qualified ethanol fuel production” means ethanol is sold by the producer to another person for use as a fuel, as a fuel component or for retail sale (26 U.S.C. § 40(b)(4)(B)(i)). While this credit is available to producers with a capacity of up to 60 million gallons per year, and the credit is only applied to the first 15 million gallons of production, a producer could only receive a maximum of $1.5 million in credits per year. At present, all three alcohol credits are scheduled to end after December 31, 2010.

The most recent revisions to the ethanol credits provide additional incentives for the production of biofuels from cellulosic processes, known as the “cellulosic biofuels producer credit.” If a facility produces cellulosic biofuel, then it may receive a $1.01 per gallon tax credit. If the biofuel is an alcohol, the credit is reduced by the amount of the alcohol mixture credit or the small producer credit as applicable (26 U.S.C. § 40(b)(6)). As with the alcohol credits, the cellulosic biofuels producer credit expires on December 31, 2010 unless Congress chooses to extend it.

Excise Tax Issues

Excise taxes are typically imposed on gasoline and diesel fuels either when the fuels leave the refinery or terminal, or upon their arrival to the U.S. if they are imported. As a result, given the assumptions stated at the beginning of this guide, these taxes will likely not apply to the reader. However, if you intend to sell your fuel to another entity, these taxes may be triggered. Be aware that the excise and income tax credits are linked via 26 U.S.C. §40(c) so that the income tax credit will be “Reduced to take into account any benefit provided with respect to such alcohol solely by reason of the application of” the excise tax credit provisions.30 Claiming these credits requires registration with IRS.31

The federal excise taxes are $0.183 per gallon (26 U.S.C. §§ 4081, 4083). Biofuels are not immune from these taxes, as 26 U.S.C. § 4041 also imposes the gasoline tax rates on ethanol. These taxes can be offset with the credits created by 26 U.S.C. § 6426 that creates the alcohol mixture credit (sometimes called the blenders credit, Volumetric Ethanol Excise Tax Credit or VEETC), and the biodiesel mixture credit. These credits amount to $0.45 per gallon for ethanol (minimum 190 proof) blended with gasoline for use as fuel and $1.00 per gallon for biodiesel mixed with petroleum-based diesel.

Additionally, there are several exemptions available for fuels used on a farming operation for farming purposes. Consult IRS Publication 510, Excise Taxes, for more information (Publication 510). Also, as previously discussed, note that the excise and income tax credits are linked via 26 U.S.C § 40(c) so that the income tax credit will be “reduced to take into account any benefit provided with respect to such alcohol solely by reason of the application of” the excise credit provisions; in other words, producers are not allowed to “double dip” from both the income tax credits and the excise tax credits.32

Additionally, there are several exemptions available for fuels that are used on a farming operation for farming purposes. Consult IRS Publication 510, “Excise Taxes,” for more information (Publication 510). Also note the excise and income tax credits are linked via 26 U.S.C § 40(c) so the income tax credit will be “reduced to take into account any benefit provided with respect to such alcohol solely by reason of the application of” the excise credit provisions; in other words, producers are not allowed to double dip from both the income tax credits and the excise tax credits.33

At the state level, an excise tax of $0.16 per gallon is imposed on gasoline and gasoline-blended fuels.34 There are, however, several potential exemptions from excise taxes including exemptions for fuel used for farm tractors or stationary engines used exclusively for agricultural purposes,35 and biofuels “produced by an individual with crops grown on property owned by the same individual and used in a vehicle owned by the same individual on the public roads and highways of this state.”36

30 26 U.S.C. §§ 4041(b)(2), 6426, and 6427(e).

31 26 U.S.C. §6426(a).

32 26 U.S.C. §§ 4041(b)(2), 6426, 6427(e), 2426).

33 26 U.S.C. §§ 4041(b)(2), 6426, 6427(e), 2426).

34 68 Okla. Stat. § 500.4(a)(1).

35 68 Okla. Stat. § 500.10(8).

36 68 Okla. Stat. § 500.10(18).

Renewable Fuels Standard (RFS)

The federal Energy Policy Act of 2005 (often called EPAct)37 established a Renewable Fuels Standard, (RFS) that mandates the inclusion of certain levels of biofuels into the U.S. fuel supply.38 For more information on the RFS, consult the “Basic Biofuels Information Guide”. Under this rule, fuel importers and refiners are required to demonstrate compliance with the requirements of the RFS by purchasing credits called “Renewable Identification Numbers” (RINs).39 Thus, if an ethanol producer wants to take advantage of the programs under the RFS, they need to register with EPA so that the fuel they produce can be assigned RINs.40 Participants also need to register with EPA’s Central Data Exchange (CDX). For more information on these registration requirements, visit the EPA’s Renewable Fuels Reporting Forms website.

37 Pub. L. 109-58 (2005).

38 42 U.S.C. § 7545(o).

39 40 C.F.R. § 80.1101(o).

40 40 C.F.R. § 80.1126.

Environmental Permitting

In Oklahoma, most environmental programs handled at the federal level by the Environmental Protection Agency are delegated to the Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ). Thus, DEQ will be the agency to handle environmental permitting for most biofuels facilities within the state. Although most on-farm ethanol production projects will be too small to require permits under many environmental programs, producers should still examine whether their operations do qualify. If it is determined that a facility was operating without a required permit, substantial penalties may be enforced.

Air Permitting

The federal Clean Air Act (CAA) 41 requires air permits for facilities that emit more than specified amounts of certain air pollutants. These permits are often called “Title V” permits and facilities required to have such permits are called “Title V” (from the title of the CAA that contains the permit requirements) and/or major sources. Facilities emitting more than the following amounts are considered to be major stationary sources of air pollution and must have a Title V permit:

Ten (10) tons per year of any individual hazardous air pollutant (HAP) or 25 tons per year of any combination of HAPs (note, a “hazardous air pollutant” is a substance found on EPA’s list of particularly dangerous air pollutants; this list is found at 42 U.S.C. § 7412(b)); OR 100 tons of any “regulated” air pollutant (these pollutants include volatile organic compounds, certain classes of airborne particles or “particulate matter,” carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide, and lead).42

A facility’s potential to emit must be compared against the emission threshold for each respective regulated air pollutant. Potential to emit is a calculation of a facility’s theoretical ability to emit regulated pollutant(s), i.e., the worst case air emissions scenario. That calculation is based on an assumption the facility will operate at its maximum capacity 24 hours a day, 365 days per year, even if it would not do so in reality.43 As a result, you need to calculate the atmospheric emissions of your facility on this basis. Major sources must receive construction approval from the DEQ prior to construction of the pollutant emitting equipment. As a result, large biofuels facilities need to begin the major source application process well before they anticipate starting facility construction or operations.

Most on-farm biofuel production facilities will not approach the major source permit thresholds. However, the DEQ also permits smaller sources of air emissions under their minor facility permit program that applies to facilities emitting more than 40 tons per year of certain regulated air pollutants, but less than major source thresholds.44 Note that facilities emitting 40 tons per year or less of actual emissions of each regulated pollutant are exempted from Title V and minor source permitting requirements.45 Also note the calculation of the “permit exempt” limits is based on actual emissions, rather than potential to emit.

If there is a question whether your facility would require a minor facility permit, you can request an “applicability determination” from DEQ.46 A request for an applicability determination must be in writing, contain all information necessary for DEQ to determine whether a permit is required, and must be accompanied by the necessary permit fee (in the case of a minor facility, this fee is $250).47 It is also possible to request evaluation of potential facility air permitting requirements through engagement of a qualified environmental consultant. Utilizing this approach can preserve the ability to self-report any compliance issues discovered during the evaluation process.

Another alternative for facilities whose potential to emit triggers the need for a major source permit is to ask DEQ for legally-enforceable limits on their operations that would reduce their emissions below the major source limits.48 These facilities are called “synthetic minor” sources. Where possible, synthetic minor source permitting can provide significant relief from the resources and expense needed to comply with a major source permit.

For more information on DEQ’s air permitting programs, visit Oklahoma Division of Environmental Quality - Air Quality Division

41 42 U.S.C. §§ 7401 et seq.

42 42 U.S.C. §§ 7661a(a), 7661(2)

43 Okla. Admin. Code §252:100-8-2 (definition of “potential to emit”).

44 Okla. Admin. Code § 252:100-7-1.1 (defining “permit exempt facility” as a facility that has actual emissions in every calendar year 40 tons per year (tpy) or less of each regulated air pollutant”).

45 See Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality “Advice for Obtaining ‘Permit Exempt’ Applicability Determinations.”

46 Okla. Admin. Code § 252:100-7-2(d).

47 Okla. Admin. Code § 252:100-7-3(a)(1).

48 See Okla. Admin. Code §§ 252:100-1-3, 252:100-8-2, defining “potential to emit” to include artificial operations limitations if those limitations are legally enforceable.

Water Issues

Generally, the federal Clean Water Act49 (CWA) requires a permit for the discharge of any pollutant into a body of water from a discrete point (such as a pipe, conduit, ditch, or channel). The CWA’s definition of pollutant encompasses an immense range of possible substances.50 If your biofuels facility will discharge only to a septic system or to a city sewage system, no discharge permit is required.51 If, however, you will be discharging to such a system, you must ensure that your discharges will not cause that system to malfunction.

On the other hand, if you will need to discharge pollutants to a water body, you will need an Oklahoma Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (OPDES) permit. Such permits must take into account the nature of the pollutants emitted by the facility, the existing quality of the water receiving the discharge from the facility, the uses of the receiving water, and the technology that could be used to treat the discharge.52 Given that many biofuels facilities have the opportunity to use different strategies for handling the water they generate (such as irrigating nearby fields and using evaporation ponds), facility developers should consult the permitting agency early in their planning process to determine if such alternatives may be approved. Generally, an applicant must submit their materials no later than 180 days prior to commencing a discharge, but in some circumstances the application must be submitted 90 days prior to construction of the discharge equipment53 (40 C.F.R. § 122.21(c)).

If your biofuels facility will be located outdoors, it may also need a permit for discharges of pollutants that occur from industrial storm water runoff (rainfall that runs off from the facility carrying potential pollutants with it). Usually this is handled by a general permit.54 If applicable to the facility, a general permit often provides coverage at a lower cost and with less needed lead time than other permits. If you are building a large biofuels facility outdoors, construction storm water regulations may also come into play. These regulations require permit coverage for potential runoff discharges from construction sites that will disturb more than one acre of land.55 As with industrial storm water permits, Oklahoma frequently handles construction storm water issues with general permits, making such permits much easier and much less expensive to obtain.

For more information on DEQ water permits, visitOklahoma Division of Environmental Quality - Water Quality Division

49 33 U.S.C. §§ 1251 et seq.

50 33 U.S.C. § 1362(6).

51 Such discharges do not constitute a “point source” discharge pursuant to the definition at 27A Okla. Stat. § 2-6-202.

52 See generally Okla. Admin. Code title 252, chapter 606, subchapter 5.

53 Okla. Admin. Code § 252:606-1-3, incorporating by reference 40 C.F.R. § 122.21(c).

54 Okla. Admin. Code § 252:606-1-3, incorporating by reference 40 C.F.R. §122.26.

55 Id.

Waste

The production of biofuels from agricultural materials generates a number of by-products and co-products, some of which may fit the definition of solid waste under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA).56 In Oklahoma, enforcement of RCRA has been delegated to DEQ. As with the definition of pollutant discussed above, the definition of solid waste encompasses almost every waste material generated by an industrial process. Such wastes must be disposed of at an RCRA-compliant landfill or by another RCRA-permitted method. Additionally, RCRA defines some solid wastes as “hazardous wastes” by both listing specific substances always considered hazardous and by setting forth chemical characteristics deemed hazardous.57 That is to say, a substance may be hazardous if either (A) it is listed on one of the RCRA hazardous lists, or (B) if the substance has a hazardous characteristic. Depending on the inputs and processes used for your ethanol production facility, you may generate some quantities of these materials. While all hazardous wastes require special storage and disposal procedures, the facility itself may face additional registration and reporting requirements if it generates more than 1,000 kilograms of hazardous waste in a month.58

Importantly, using co-products or by-products (for example, applying them as fertilizers or making other products out of them) can exclude those materials from the definition of solid waste. Since this may significantly reduce the costs of waste management and/or provide additional cash flows, you should carefully review your fuel production processes to determine how all the facility’s resources can be used or reused for maximum efficiency.

More information on DEQ’s waste programs

56 42 U.S.C. §§ 6901 et seq. Oklahoma’s Solid Waste Management Act is found at 27A Okla. Stat. § 2-10-101.

57 40 C.F.R. § 261.3.

58 40 C.F.R. § 260.10, 40 C.F.R. Part 262, generally.

Tank Storage Issues

Generally, the regulation of chemical storage tanks in Oklahoma is overseen by the Oklahoma Corporation Commission (OCC) and DEQ.59 The tank storage of chemicals is regulated through two main programs. First, the Spill Prevention, Containment, and Countermeasure (SPCC) program applies to above-ground storage tank facilities containing 1,320 gallons or more of oil and oil products.60 For the purposes of the SPCC program, however, oil and oil products is defined as “oil of any kind or in any form, including, but not limited to: fats, oils, or greases of animal, fish or marine mammal origin; vegetable oils, including oils from seeds, nuts, fruits or kernels; and other oils and greases, including petroleum…”61 Ethanol would not fall into this definition, thus, the storage of ethanol alone will likely not trigger the SPCC requirements. However, for ethanol facilities, a primary concern would be gasoline used as a denaturant. If a large tank is used to store gasoline for denaturing, that tank may trigger SPCC requirements. Facilities subject to the SPCC regulations must prepare a spill prevention, containment, and countermeasure plan that may include requirements to build secondary containment structures (such as curbs or berms) around tanks and must provide contingency plans for responding to a spill of regulated materials.62

The second tank storage program, the Underground Storage Tank (UST) program, regulates tank systems containing “regulated substances” constructed with ten percent or more of their volume underground.63 “Regulated substances” represents yet another broadly encompassing definition and includes substances regulated under a number of other regulatory programs including hazardous substances64 and petroleum products.65 Again, this definition includes many substances commonly stored at biofuels facilities. Owners of regulated tank systems must register with either OCC or DEQ (depending on the stored substance as discussed above), install and maintain leak detection and corrosion protection systems, and keep records of material inventories and maintenance operations.66 More information about storage tank regulations can be found on the OCC’s Petroleum Storage Tank division’s website.

59 27A Okla. Stat. §§1-3-101(E)(5), (7).

60 40 C.F.R. § 112(b).

61 40 C.F.R. §§ 112.1(b), 112.2.

62 40 C.F.R. §§ 112.3, 112.7.

63 40 C.F.R. § 280.12. See also Okla. Admin. Code § 165:25-1-11.

64 42 U.S.C. § 9601(14).

65 Tanks coming under OCC’s jurisdiction are those tanks containing “antifreeze, motor oil, motor fuel, gasoline, kerosene, diesel or aviation fuel [and] does not include compressed natural gas.” Okla. Admin. Code § 165:25-1-11. Per 27A Okla. Stat. §§1-3-101(E)(5), (7), regulated tanks that are not under OCC’s jurisdiction are placed under DEQ jurisdiction.

66 40 C.F.R. Part 280.

Community Right-To-Know Issues

Another potentially applicable regulatory system is the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA), also known as SARA Title III (because EPCRA formed Title III of the Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act). EPCRA requires communication between a facility storing specified amounts of potentially dangerous substances and local emergency response agencies, and establishes reporting requirements to help local emergency officials understand the inventories of such substances in their areas. One can find a list of substances that may trigger EPCRA applicability by consulting EPA’s List of Lists, available at http://www.epa.gov/ceppo/pubs/title3.pdf. Any prospective biofuels project should review its process design to determine if it will hold inventories of any EPCRA-covered substances. Generally, you should communicate with your local emergency services (firefighters, emergency medical, and local sheriff’s and police departments) so emergency responders are aware of any potential hazards present at your biofuels operation. This will provide greater safety for both you and them.

Table 1 presents a list of typical ethanol production inputs and outputs, with notes of substances that may trigger EPCRA reporting requirements.

Table 1: Typical Ethanol Inputs and Outputs.

Inputs

- Yeast

- The Sugar Method of Fermentation

- Enzymes

- Alpha Amylase

- Glucoamylase

- Cellulase

- Feedstocks

- Waste or culled fruit

- Peas

- Sugar Beets

- Foder Beets

- Molasses

- Candy Waste

- Syrup from Sorghum Stalks

- Sugarcane

- Inputs for Nutritional Adjustments

- Diammonium Phosphate (Barley Malt)

- Kelp

- Calcium Sulfate (Agricultural Gypsum)

- Inputs for pH adjustment

- Calcium Hydroxide (Lime)

- Sulfuric Acid* * Requirements triggered at 1,000 lbs. in storage

- Phosphoric Acid* * Must report releases of 5,000 lbs. or more

- Lactic Acid

- Enzymes

- The Starch Method of Fermentation

- Enzymes

- Alpha Amylase

- Glucoamylase

- Feedstocks

- Corn

- Wheat

- Barley

- Potatoes

- Peas

- Cassava or Tapioca Root

- Plantains

- Breadfruit

- Unripe Bananas

- Buffalo Gourd

- Inputs for Nutritional Adjustments

- Calcium Sulfate (Agricultural Gypsum)

- Calcium Hydroxide (Lime)

- Enzymes

Outputs and By-products

- Output

- Ethanol

- By-products

- Carbon Dioxide

- Distillers Grain

- Water

You can learn more about EPCRA from the DEQ’s Risk Communication page.

Employee Safety

Boilers

Many ethanol facilities will use one or more boilers as part of the production process. Boilers (other than those used for household or commercial hot water applications) generally must be approved and routinely inspected by the Oklahoma Department of Labor (DOL) pursuant to the Oklahoma Boiler and Pressure Vessel Safety Act.67 However, there are several exemptions from these requirements. The following types of boilers are exempt from the Act:

- Pressure vessels having an internal or external operating pressure not exceeding fifteen (15) pounds per square inch gauge [one hundred three (103) kilopascals gauge] with no limit on size;

- Pressure vessels having an inside diameter not exceeding six (6) inches (152mm) with no limitation on pressure;

- Pressure vessels containing water heated by steam or other indirect means when none of the following limitations is exceeded:

- A heat input of two hundred thousand (200,000) British thermal units per hour fifty-eight thousand six hundred (58,600) watts,

- A water temperature of two hundred ten degrees Fahrenheit (210 F), or

- A water containing capacity of one hundred twenty (120) gallons—four hundred fifty (450) liters.68

Unless your boiler falls under one of the Act’s exemptions, an annual inspection of the boiler by a DOL inspector will be necessary.69

67 40 Okla. Stat. §§ 141.1, et. seq.

68 40 Okla. Stat. § 141.2.

69 Okla. Admin. Code § 380:25-3-2.

Hazard Communication

While most on-farm biofuels production facilities may not have many employees, if any, it is a good idea to follow the requirements of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA) Hazard Communication Standard (HCS). While you may not have heard of the HCS, you have probably heard of its primary tool — the Materials Safety Data Sheet, or MSDS. If you have any employees, you are required to keep copies of any MSDS for any hazardous chemicals in storage or in use.70 In any event, having MSDS sheets available in a conspicuous place at the production facility is always advisable, as the information may be important for you and/or for emergency responders at the facility. For more information on the HCS and MSDS, visit OSHA’s Hazard Communication website. A summary of guidelines for employer compliance is available at (Appendix E to 29 C.F.R. Part 1910).

70 29 C.F.R. § 1910.1200(b)(3(ii).

Building and Zoning Restrictions

The first step in addressing building and zoning restrictions that may apply to your biofuels facility is to determine whether your facility lies within the jurisdiction of a city or town that has an enforceable code (other than rural areas in Oklahoma County and Tulsa County, very few areas outside the boundaries of a municipality are under any zoning or building code authority).71 Even if your facility is in a rural area, that area may be within the annexed limits of a nearby city or town. Thus, always confirm the zoning status of your operation with the city engineering office of your nearby towns and cities.

If your facility will be within the jurisdiction of a city or town with an enforceable code, several different ordinances may apply to your operation. Zoning restrictions may apply to fuel production operations. For example, fuel production operations may be restricted to commercial or industrial areas and may not be allowed in residential or agricultural areas. However, read these regulations carefully; often, code enforcement officials may simply assume that a zoning restriction applies to your operation without understanding the scale of your operation. Meet with code enforcement officials and be prepared to fully explain the scope and operation of your fuel production system.

In addition to zoning restrictions, fire codes, electrical codes, and building codes may also apply to the construction and operation of your fuel production operation. These codes may vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Consult your city or town’s office to determine the code provisions that apply to your operation. Many times, local jurisdictions will adopt national codes, either outright or with modifications. Copies of these codes are sometimes kept at your local library.

71 11 Okla. Stat. § 43-101 (cities given authority to enact zoning codes); 19 Okla. Stat. chapter 19A (zoning limitations on Oklahoma counties).

Conclusion

On-farm ethanol production provides an opportunity for agricultural producers by enabling them to produce their own fuels from their own products. This can potentially provide an important fuel cost management tool to the producer. However, many of the regulations that apply to large refineries do not carry exemptions for small-scale production of fuels, and as a result, those who produce fuel simply for their own use may often face the same regulations as a large, commercial refinery. Conduct a careful evaluation of your planned biofuels production facility and determine the applicability of these regulations before proceeding. In the case of fuel production, it is definitely easier to ask permission than forgiveness.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Permitting Programs

EPA Facility Registration Forms:

EPA Fuel Registration Forms:

EPA Renewable Fuels Reporting Forms:

DEQ Air Permitting Programs

DEQ Water Permitting Programs

DEQ Solid Waste Programs

DEQ Risk Communications Page

Oklahoma Basic Biofuels Information Guide

Appendix 3

Web References for Additional Information

This publication released by EPA Region 7 lists the federal laws and EPA regulations that a person must abide by when constructing or modifying an ethanol plant

Guide specifies in aid of planning the location for an ethanol plant, determining feasibility, and provides information about financial aspects and incentives of developing an ethanol plant. Produced by the Nebraska Ethanol Board in cooperation with the USDA.

Congressional Research Service Publication which primarily discusses general information on the national level, such as greenhouse gas emission information and an overview of the ethanol industry. Also provides useful economic information with the possibility programs that a producer could use to start a small-scale ethanol production facility.

Arkansas University of Law – Ag Law Research Publication citing specific citations for the state of Oklahoma in regard to ethanol and biodiesel production. Citations cited specifically provide policy information regarding biofuel development in the state as well as financial incentive/tax information.

CRS Congressional Report that discusses the many federal economic and tax incentives for producing biofuel ethanol and biodiesel. Provides information about tax breaks and loan programs.

CRS publication that cites a broad range of federal statutes dealing with the financial, environmental, and economical aspects of biodiesel and ethanol production.

Publication released by Oklahoma Department of Agriculture, Food and Forestry, which summarizes the Fuel Alcohol Act.

Publication released by Oklahoma Department of Agriculture, Food and Forestry, which additionally discusses fuel ethanol regulations for the state of Oklahoma, as defined by the ODAFF.

Fact sheet discussing biodiesel production released by the Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality.

List of Ethanol Tax Credits for Producers/Retailers in the State of Oklahoma.

List of Federal Ethanol Tax Credits and Laws compiled by the US Department of Energy

Web site of the Renewable Fuels Association, an advocacy group solely dedicated to the production of ethanol in the U.S. Web site provides a wealth of information regarding environmental, economic, and agricultural impacts of ethanol.

Web site of the American Coalition for Ethanol, an advocacy group solely dedicated to the production of ethanol in the U.S. Web site provides a wealth of information regarding environmental, economic and agricultural impacts of ethanol.

Shannon L. Ferrell

Assistant Professor, Agricultural Law

Daniel Skipper

Area Agricultural Economics Specialist

G. Blake Jackson

Extension Research Assistant