Grid Pricing of Fed Cattle: Base Prices and Premiums-Discounts

A companion extension facts (WF-557, Fed Cattle Pricing: Grid Pricing Basics) included an example of grid pricing and some of the implications from using price grids. The objective of this extension facts is to specifically distinguish formula pricing from grid pricing, discuss price discovery implications from using alternative base prices with premium-discount grids, and show how premiums and discounts have varied over time.

Formula Pricing versus Grid Pricing

Formula pricing refers to establishing a transaction price using a formula that includes some other price as a reference. Formula prices are not discovered for each transaction. Rather, some other price is used; a price discovered external to the particular formula priced transaction.

Grid pricing consists of a base price with specified premiums and discounts for carcasses

above and below a base or standard set of quality specifications. Grid pricing may

use a formula for establishing the base price. Interviews with feeders and packers

revealed several base prices being used (Schroeder et al.):

- Average price (cost) of cattle purchased by the plant where the fed cattle were scheduled to be slaughtered for the week prior to or the week of slaughter

- Specific market reports, such as the highest reported price for a specific geographic market for the week prior to or week of slaughter

- Boxed beef cutout value

- Futures market price

- Negotiated price.

Of these methods, all involve formula pricing except where base prices are established by negotiation. Thus, grid pricing is not necessarily similar to formula pricing. Formulas have one thing in common; all are based on some external price. Therefore, all require a minimal amount of market information to establish prices across transactions under the same formula. However, important differences exist among the formulas. These differences include the source of the external price (for example, plant averages vs. USDA quoted prices) and the market level of the external price (for example, live or carcass weight cash market, futures market, or wholesale beef market). These differences lead to important implications regarding the formula pricing method and impacts on other markets.

The final transaction price with most grid pricing methods is established after fed

cattle have been slaughtered. Most grids are based on dressed or carcass weights.

The intent is to assign higher prices to higher quality cattle and lower prices to

lower quality cattle. Both feeders and packers indicated that premiums and discounts

present in grids also varied (Schroeder et al.). Some were based on:

- Plant averages

- Wholesale price/value spreads

- Negotiated values.

Grid premiums and discounts based on plant averages are related to the quality of cattle being delivered to a specific plant. In contrast, those based on wholesale price spreads reflect wholesale supply and demand conditions for boxed beef.

To summarize, formula pricing is not necessarily grid pricing, and grid pricing does

not necessarily involve formula pricing. Formula pricing usually refers to the method

of finding the base price in grid pricing systems. Formula pricing relies on prices

discovered for transactions external to the ones involving the formula. The base price

in grid pricing may be established by a formula but may also be negotiated between

feeders and packers.

Base Prices and Price Discovery

Grid pricing attempts to better match price with quality, thus rewarding producers for marketing higher quality carcasses and penalizing them for marketing lower quality carcasses. Perhaps the most significant concern regarding grid pricing is the method of establishing the base price. Base prices that are formula prices (those using either plant averages or live or dressed weight reported prices), raise serious concerns from the standpoint of price discovery and pricing accuracy.

Base prices that depend on plant averages vary over time due to the types of cattle

processed during the time period for which the plant average is calculated. This variation

is not necessarily consistent with market trends, and the plant average base prices

can send incorrect market signals to producers.

Base prices derived from plant averages or from live or dressed weight reported prices,

may not represent the type of cattle being marketed with the grid. The type of cattle

typically being marketed on a grid system would be higher quality cattle targeted

towards meeting grid premiums and avoiding discounts. The cattle on which plant averages

or reported market prices are based may not be the same quality as cattle being priced

with a grid; and in fact, may be lower quality. Thus, formula base prices may decline

(relative to previously) as increased numbers of higher quality cattle are diverted

away from the cash market to grids. Also, reference prices in formula base prices

can become thinly traded, making them less reliable as an accurate reflection of market

conditions. For these reasons, base prices that are formula priced using plant averages

or other cash market trades are problematic for the producer involved in grid pricing

and are detrimental to overall price discovery.

Base prices do not need to be formula arrangements. They can be negotiated, market

reported prices like other carcass weight (in the beef) transaction prices for fed

cattle. Negotiated base prices are relatively expensive to discover in terms of information

needed by the parties involved. They do not rely on potentially unrepresentative prices

such as plant averages. In addition, negotiated base prices would contribute to market

information and subsequent price discovery.

When using formula pricing to establish the base price in grid pricing, reference

prices discovered in competitive markets is essential. One alternative is to tie the

base price to the reported wholesale-level, for example boxed beef cutout values or

to reported boxed beef prices. Packers have an incentive to increase wholesale prices

as much as possible to increase packer revenues. Thus, the base price is tied to a

price which packers have an economic incentive to raise, rather than tied to cash

market or plant average prices which packers have an economic incentive to lower.

Another possibility is tying the base price to a futures market price, an alternative

market for price discovery. Either of these alternatives is subject to fewer problems

than those discussed for base prices that include formulas tied to plant averages

or reported cash market prices. These formulas are less susceptible to thin trading

or of moving randomly in ways not reflective of market conditions. Formula prices

have advantages that include keeping costs of price discovery low for the parties

involved. From this perspective, formulas based on wholesale boxed beef cutout or

live cattle futures prices involve both low cost to negotiate and yet are representative

of market conditions.

Premiums and Discounts Over Time

Premiums and discounts associated with various carcass traits vary across packers at any point in time. Premium-discount grids are reported weekly by the Agricultural Marketing Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture (AMS-USDA) in its National Weekly Direct Slaughter Cattle Premiums and Discounts report. In the six-packer survey of grid prices for the week of December 11, 2000 (prior to mandatory price reporting), the range in premiums for Prime quality grade carcasses was from $3/cwt to $14/cwt over Choice grade carcasses. Select grade carcass discounts typically closely follow USDA wholesale Choice to Select boxed beef price spreads. Nonetheless, Select grade carcasses had discounts ranging from $7/cwt to $8.50/cwt across packers relative to Choice quality grade. Standard grade carcass discounts relative to Choice ranged from $9/cwt to $32/cwt. Premiums for yield grade 1-2 relative to yield grade 3 ranged from $0/cwt to $6.50/cwt, and discounts for heavy weight carcasses (greater than 950 lb) ranged from $5/cwt to $30/cwt.

Premium-discount differences among packers are likely related to the kinds of market

opportunities different packers have for merchandising beef of varied quality, as

well as to the handling/sorting/processing cost differences that may be present for

carcasses having varied attributes across different plants or firms. The important

point regarding this variability is that a producer needs to compare several grids

for the type of cattle the producer has in order to determine which grid offers the

highest expected price without undue risk for large discounts. Varying base prices

should also be considered when a producer assesses various grid price alternatives.

Producers need to understand that premiums and discounts vary over time due to wholesale

beef market conditions. Some premiums and discounts are more stable and predictable

than others. This information is important if producers make production decisions

targeting particular grid price signals. How likely is it that producers will realize

premiums close to the ones expected at the time the production decision was made (whether

breeding, purchasing, or feeding decisions)? Longer run genetics decisions, feeder

cattle purchasing, and feeding management decisions which are oriented toward value-based

systems are necessary but are difficult if the “target” continues moving. Therefore,

stability of the marketing target is important.

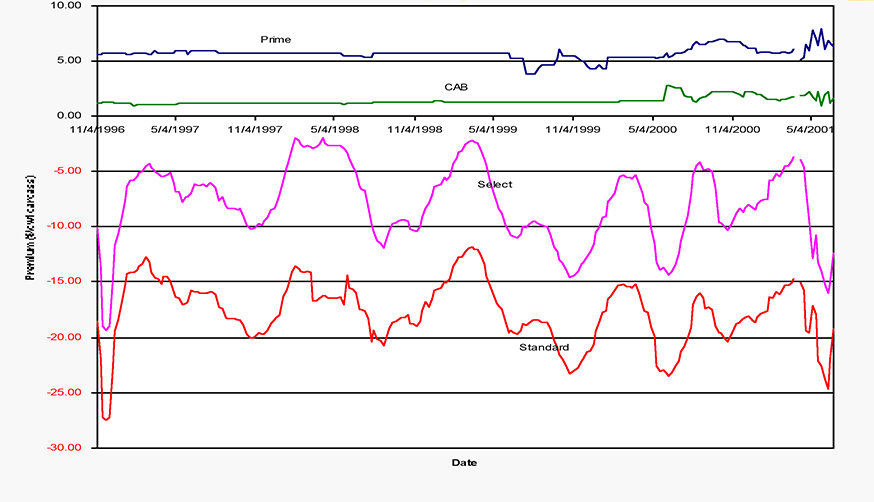

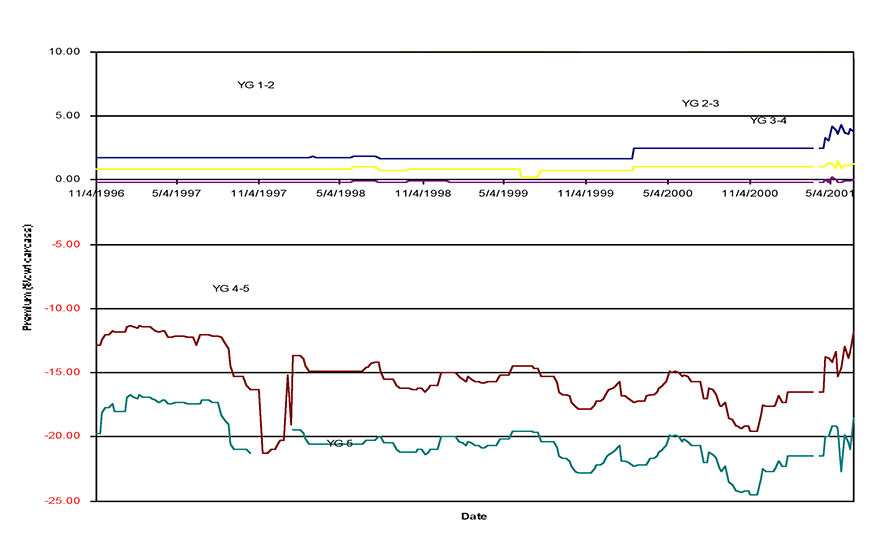

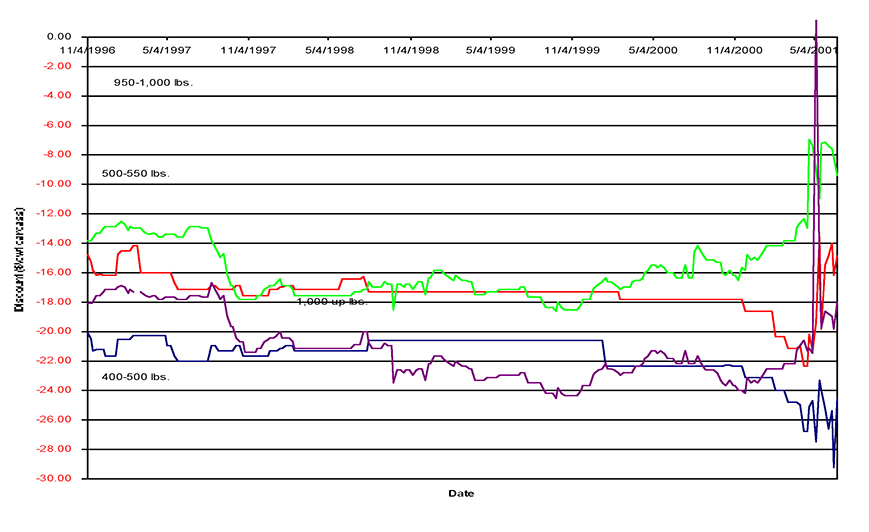

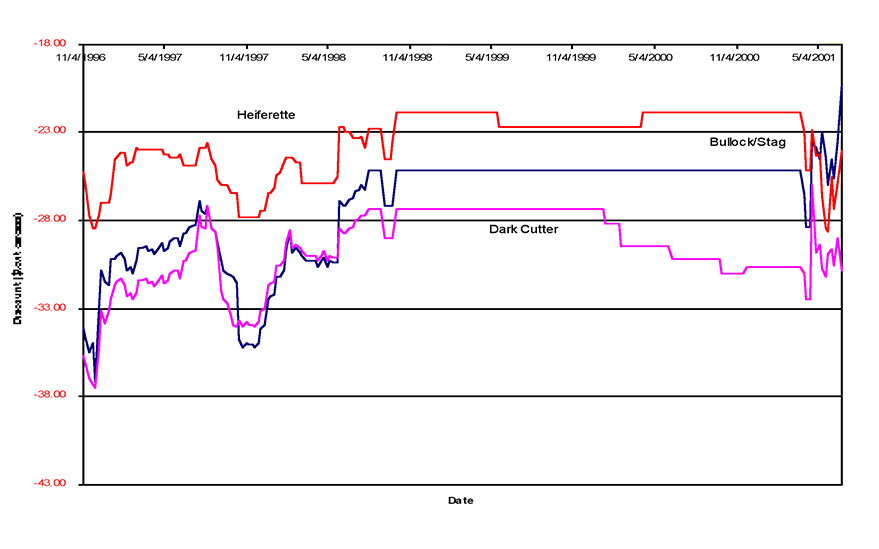

Figures 1-4 illustrate trends in average USDA reported grid premiums and discounts

for various carcass attributes over the time period for which such data are available.

Quality grade premiums and discounts are quoted relative to Choice. Average premiums

for Prime and Certified Angus Beef have been stable over the time period whereas discounts

for Select and Standard quality beef vary considerably (Figure 1). The average discount

for Select carcasses relative to Choice closely matches the USDA Choice-to-Select

price spread for wholesale boxed beef on a weekly basis. Standard discounts are typically

$8/cwt to $10/cwt greater than the Select discount.

Yield grade premiums and discounts are illustrated in Figure 2. Yield grade 1 and

2 carcasses have had relatively stable premiums compared with discounts for yield

grade 4 and 5 carcasses. Yield grade 4 and 5 discounts are relatively large and have

varied over time by as much as $5/cwt. Price discounts for heavy or light carcasses

(Figure 3) and dark cutters and other “out” carcasses (Figure 4) vary considerably

over time.

Management of cattle can help deal with some of the variability associated with selected grid premiums and discounts. For example, close sorting of cattle can reduce the incidence of and discounts for heavy and light carcasses. To some extent, careful handling may help reduce the incidence of and discounts for dark cutters. Perhaps adoption of ultrasound or other imaging technology at the feedlot can improve management of yield grades by helping signal when to market cattle, reducing the incidence of yield grades 4 and 5 carcasses. Longer run management of cattle genetics may help target higher quality grades of beef, reducing risk associated with widely varying Select and Standard discounts.

Pricing Alternatives and Terms of Trade

Table 1 contains a summary and comparison of issues associated with typical fed cattle pricing alternatives. Differences across the various methods of marketing fed cattle are important because price will likely differ across the various pricing methods. Prices may differ for the same pen of cattle because different kinds of information are used in the various pricing methods to arrive at a price. The key element is that as a producer moves from live weight pricing, to dressed weight pricing, to grid pricing, it is increasingly important to understand the type of cattle being marketed, and the pricing system being used to assess the net price received.

Table 1. Assessing Ways to Market Fed Cattle.

| Fed Cattle Pricing Method | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pricing Attribute | Live | Dressed | Grid | |

| Value Based Pricing Level | No Pen | No Pen | Yes Individual carcass | |

| Quality Premiums/ Discounts | Minimal | Minimal | Yes | |

| Yield Premiums/Discounts | Minimal | Minimal | Yes | |

| Price Range Across Carcasses | ||||

| Trucking Costs Paid by Base Price | None Buyer Live |

None Seller Dressed |

High Seller Formula or negotiated |

|

| Carcass Performance | Risk | Buyer | Buyer | Seller |

Conclusions and Implications

Since base prices often vary and both premiums and discounts vary from one packer to another, producers must understand how price is computed. With plant-average formula-based grid pricing, cattle quality is paid for on the basis of each producer’s cattle quality relative to other cattle slaughtered previously in the same plant. With other base prices and premium-discount grids, cattle quality is being priced on its own merit, not relative to other cattle.

Many grid pricing systems use formula prices to establish the base. Base prices in

grid pricing do not need to be formula based. The most concern regarding base prices

is with those that are based on plant average prices. Formula base prices based on

plant averages reduce the availability of prices which can be reported, do not contribute

to price discovery, change across plants as the quality of cattle slaughtered changes

and may not be representative for the cattle being marketed using a grid.

Grid pricing has several economically desirable attributes. However, to be used effectively

by cattle producers, the grid pricing method needs to be understood thoroughly, including

differences in premium-discount grids among packers and how premium-discounts change

over time. In addition, cattle quality characteristics must be estimated accurately

to avoid a few low-quality, discounted animals offsetting many high-quality animals

receiving premiums.

References

Schroeder, T.C., C.E. Ward, J. Mintert, and D.S. Peel. “Beef Industry Price Discovery: A Look Ahead.” Price Discovery in Concentrated Livestock Markets: Issues, Answers, Future Directions. W.D. Purcell, ed. Blacksburg, VA: Research Institute on Livestock Pricing, February 1997.

Ward, C.E., D.M. Feuz, and T.C. Schroeder. Formula Pricing and Grid Pricing Fed Cattle:

Implications for Price Discovery and Variability. Blacksburg, VA: Research Institute

on Livestock Pricing, Research Bulletin 1-99, January 1999.

Clement E. Ward

Oklahoma State University

Ted C. Schroeder

Kansas State University

Dillon M. Feuz

University of Nebraska