Foot Rot in Cattle

Foot rot is a sub-acute or acute necrotic (decaying) infectious disease of cattle, causing swelling and lameness in at least one foot. This disease can cause severe lameness and decreased weight gain or milk production. A three-year study reported that affected steers gained 2.3 pounds per day, while steers not affected gained 2.76 pounds per day (Brazzle. 1993). Lame bulls and females will be reluctant to breed. If treatment is delayed, deeper structures of the foot may become affected, leading to chronic disease and a poor recovery prognosis. Severely affected animals may need to be culled from the herd. The incidence of foot rot varies according to the weather, season of the year, grazing periods and housing system. Foot rot is usually random in occurrence, but the disease incidence may increase up to 25 percent in high-intensity beef or dairy production units. Approximately 20 percent of all diagnosed lameness in cattle is actually foot rot.

Cause

Fusobacterium necrophorum is the bacterium most often isolated from infected feet. This organism is present on healthy skin, but it needs injury or wet skin to enter the deeper tissue. F. necrophorum appears to act cooperatively with other bacteria, such as Porphyromonas levii, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli and Truperella pyogenes, thereby decreasing the infective dose of F. necrophorum necessary to cause disease. Prevotella intermedia has also been implicated as causative agent for foot rot.

Normal healthy skin will not allow the bacteria to enter the deeper tissues. Moisture,

nutrient deficiency, injury or disease can result in compromised skin or hoof wall

integrity, increasing the likelihood of the bacteria invading the skin. Deficiencies

of zinc, selenium and copper can lead to higher frequency of foot rot infections due

to the important role these trace minerals play in skin and hoof integrity as well

as immune function. Injury is often caused by walking on abrasive or rough surfaces

such as stony ground, sharp gravel and grazing stubble on recently mowed pasture,

which may irritate the interdigital skin. Standing in pens or lots heavily contaminated

with feces and urine softens the skin and provides high exposure to the causative

bacteria. High temperatures and humidity will also cause the skin to chap and crack,

leaving it susceptible to bacterial invasion.

Transmission

Feet infected with F. necrophorum serve as the source of infection for other cattle by contaminating the environment. F. necrophorum can be isolated on non-diseased feet, as well as in the rumen and feces of normal cattle. Porphyromonas levii and Prevotella intermedia also can be isolated from the alimentary system of cattle. Since these organisms are part of the normal gut flora, they are readily available to contaminate the environment. Porphyromonas levii (formerly Bacteroides nodosus), the organism causing foot rot in sheep, may cause an interdigital skin surface infection in cattle, allowing entrance of F. necrophorum, thereby causing foot rot. Therefore, multi-species grazing may increase the incidence of foot rot. Once loss of skin integrity occurs, bacteria gain entrance into subcutaneous tissues and begin rapid multiplication and production of toxins, further stimulating continued bacterial multiplication and penetration of infection into the deeper structures of the foot.

Clinical Signs

Foot rot occurs in all ages of cattle, with increased incidences during wet, humid conditions. When case incidence increases in hot and dry conditions, attention must be directed to loafing areas, which are often crowded and extremely wet from urine and feces deposited in small shaded areas. The first signs of foot rot include:

- Extreme pain leading to sudden onset of lameness, which increases in severity as the disease progresses.

- Acute swelling and redness of interdigital tissues and adjacent coronary band.

- Lesions in the interdigital space are often necrotic along its edges and have a characteristic foul odor.

- Evenly distributed swelling around both digits and the hairline of the hoof, leading to separation of the claws.

- Loss of appetite.

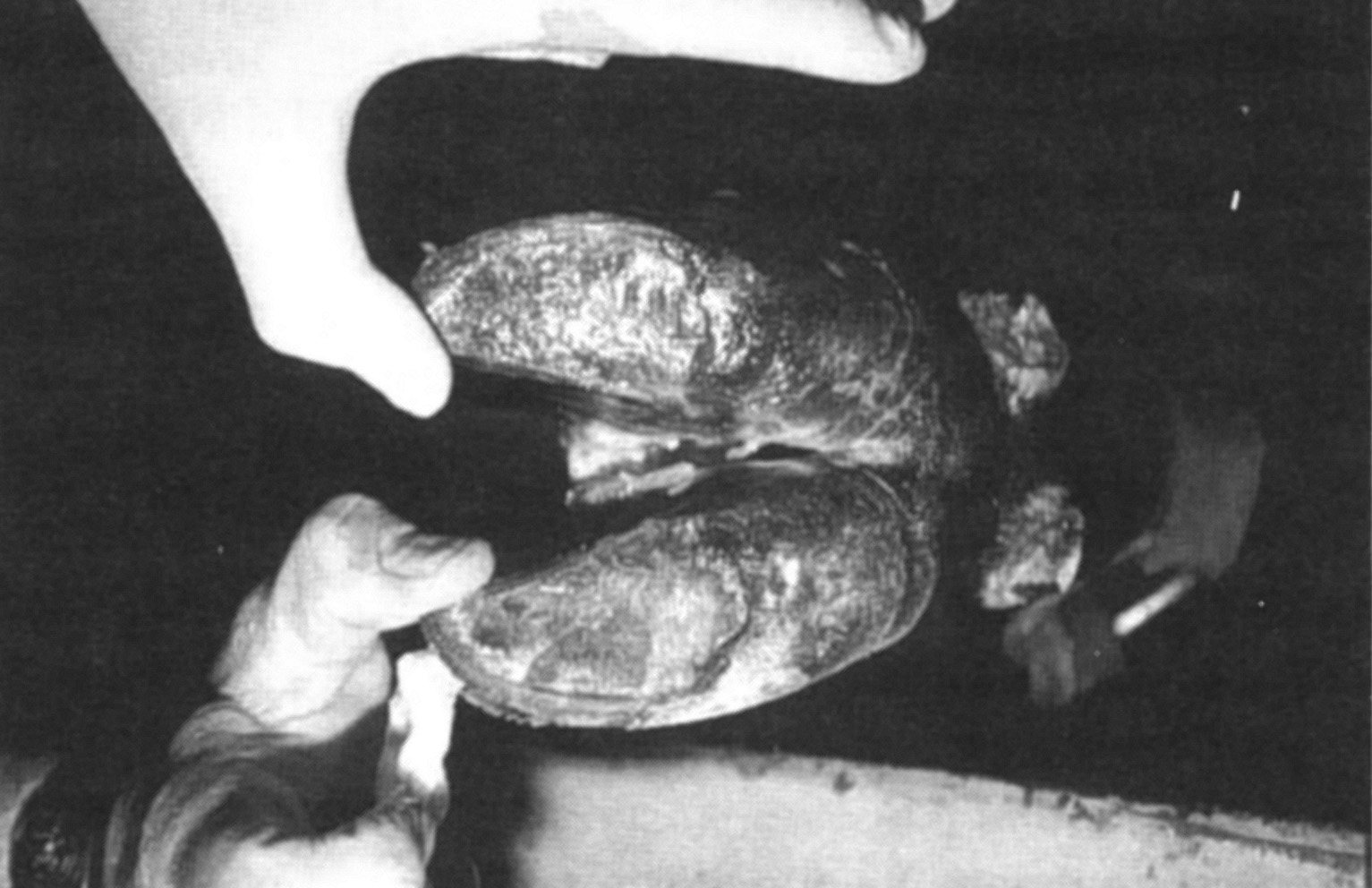

Figure 1. Foot rot in a cow showing separation of the interdigital skin, revealing a whitish-yellow necrotic core-like material.

The lesions can be difficult to see unless the foot is picked up. It can affect both the front and hind limbs. It initially affects a single foot in most cases. Eventually, the interdigital skin cracks, revealing a foul-smelling, necrotic, core-like material (Figure 1). If untreated, the swelling may progress up the foot to the fetlock or higher. More importantly, the swelling may invade the deeper structures of the foot, such as the navicular bone, coffin joint, coffin bone and tendons. “Super foot rot,” seen in some areas of the country, has received this name due to the rapid progression of symptoms, severity of tissue damage and lack of response to standard treatments. The standard foot baths have not been effective in preventing the “super foot rot” form of the disease. Veterinary supervision and early therapy results in a more satisfactory outcome.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of foot rot can be made by a thorough examination of the foot, looking at the characteristic signs of sudden onset of lameness (usually in one limb), elevated body temperature, interdigital swelling and separation of the interdigital skin. Other foot conditions causing lameness that may be confused with foot rot are: interdigital dermatitis, sole ulcers, sole abscesses, sole abrasions, infected corns, fractures, septic arthritis and inflammation or infection of tendons and tendon sheaths, all of which often involve one claw of the foot only. Swelling attributable to foot rot involves both claws.

Digital dermatitis (hairy heel warts) is often confused with foot rot because of foot

swelling and severity of lameness. Digital dermatitis affects only the skin, beginning

in the area of the heel bulbs and progressing up to the area of the dewclaws; whereas,

foot rot lesions occur in the interdigital area and invade the subcutaneous tissues.

Cattle grazing endophyte infected fescue pastures may develop fescue foot, which has

similar symptoms. Fescue foot is the result of loss of blood circulation to the foot

and subsequent lameness.

Treatment

Treatment of foot rot is usually successful, especially when instituted early in the disease course. Treatment should always begin with cleaning and examining the foot to establish that lameness is actually due to foot rot. A veterinarian may advise recommended antibiotics and dosages for each situation. Use of a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory product may be indicted for pain relief. There are multiple antimicrobial products labeled for the treatment of foot rot. These products should be used rather than using another product in an extra-label manner. A product specifically labelled for pain associated with foot rot is now available.

Affected animals should be kept in dry areas until healed, if possible. If improvement is not evident within three to four days, it may be an indication that the infection has invaded the deeper tissues. Infections not responding to initial treatments need to be re-evaluated by a veterinarian in a timely manner. A veterinarian will determine if re-cleaning, removing all infected tissue, application of a topical antimicrobial and bandaging are appropriate, along with a change in the antimicrobial regimen. In severe cases, options may be limited to harvesting the animal (following drug withdrawal times), claw amputation or claw-salvaging surgical procedures. A veterinarian will be able to provide information needed in making this decision.

Prevention

Prevention and control of foot rot begins with management of the environment. Prevention

of mechanical damage to the foot caused by frozen or dried mud, brush stubble and

gravel is desirable. Minimize animals’ exposure to sharp plant stubble and sharp gravel.

Attempt to minimize the time cattle must spend standing in wet areas. Pens should

be well-drained and frequently scraped and groomed. Areas around ponds, feed bunks

and water tanks should be maintained to minimize mud and manure.

Other preventive measures presently used include foot baths (most often used in confinement

beef or dairy operations) and addition of organic and in-organic zinc to the feed

or mineral mixes and vaccination. When cattle are moderately to severely deficient

in dietary zinc, supplemental zinc may reduce the incidence of foot rot. Zinc is important

in maintaining skin and hoof integrity; therefore, adequate dietary zinc should be

provided to help minimize foot rot and other types of lameness. A three-year study

(Brazle, 1993) has shown zinc methionine added to a free-choice mineral supplement

reduced the incidence of foot rot and improved daily weight gain in steers grazing

early summer pasture (Table 1).

Table 1. The effect of zinc methionine in a mineral mixture on gain and incidence of foot rot on steers grazing native pastures.

| Ingredient | Zinc Methionine | Control |

|---|---|---|

| Number of steers | 342 | 354 |

| Starting wt., lbs. | 583 | 587 |

| Daily gain, 93 days, lbs. | 2.79 | 2.71 |

| Incidence of foot rot, % | 2.45 | 5.38 |

| Daily mineral intake, lbs. | .24 | .22 |

| Daily zinc methionine intake, g. | 5.4 | - |

A commercial vaccine approved for use in cattle as a control for foot rot is available. Reported results by producers and veterinarians have been mixed from their use of this product and controlled studies have not been reported. Feeding chlortetracycline (CTC) to help control foot rot is not an option because CTC is not labelled for that purpose. Feed additives cannot be used in an extra-label manner and a veterinarian cannot write a Veterinary Feed Directive for extra-label drug use. By knowing a specific geographic area, a local veterinarian will be able to assist in initiating preventive measures for foot rot.

Summary

Foot rot is a major cause of lameness in cattle and can have a severe economic impact on animal health, animal performance and enterprise profitability. Skin and hoof lesions allow bacteria to invade live tissue. Therefore, the most important preventive measures are centered on the protection of interdigital skin health. Important preventative measures include a well-balanced mineral nutrition program and minimizing exposure to conditions that may cause skin or hoof injury. Treatment is frequently successful if the disease is diagnosed and treated soon after symptoms develop.

References

Brazzle F.K. 1993. Cattleman’s Day Report of Progress 704. Agriculture Experi-ment Station. Kansas State University.

Maas J, Davis LE, Hempstead C, Berg JN, Hoffman KA.

Rosslyn Biggs, DVM

Beef Cattle Extension and Director of Continuing Education

Center for Veterinary Health Sciences

Barry Whitworth, DVM

Area Food Animal Quality and

Health Specialist for Eastern Oklahoma

John Gilliam, DVM, MS, DACVIM, DABVP

Clinical Assistant Professor of Food Animal Production

Medicine and Field Services, Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital

Meredyth Jones, DVM, MS, DACVIM

Clinical Assistant Professor of Food Animal Production

Medicine and Field Services, Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital

David Lalman, PhD

Extension Beef Cattle Specialist and Harrington Chair

Department of Animal and Food Sciences