Developing Cash Lease Agreements for Farmland

- Jump To:

- Determining a Fair Rent

- Example Calculations

- Market Approach

- Landlord’s Ownership Costs and Return to Equity

- Residual Income Method

- Converting Crop Share to Cash Basis

- Adding Flexibility to Your Cash Agreement

- Putting the Agreement in Writing

- Summary and Conclusions

- The Cash Lease

- Additional Information

Cash leases and crop share leases are common rental arrangements for cropland in Oklahoma. Cash leases may require a fixed payment, either cash or a specified yield (for instance, 10 bushels of wheat). In crop share leases, income and certain costs are shared between tenant and landlord and management decisions may be made jointly. Rental agreements and rates are influenced by many factors: the location and quality of land, improvements on the land, the landowner’s costs, the tenant’s expected earnings, previous rates charged, competition for the land, government programs, tax laws, the general economy, the party’s willingness and ability to bear risks, desired land management practices, and the personal relationship between tenant and landlord.

Landowners and tenants must choose a type of lease agreement: fixed or flexible cash arrangements, crop share, or some combination. Each type of arrangement has advantages and disadvantages. Landowners and tenants should each consider the following questions when choosing a type of lease agreement.

- What portion of income do I receive?

- What portion of costs do I contribute?

- What portion of the risk do I bear?

- What crop and land management practices will be followed?

- What will be the condition of the land after the term of the lease?

The purpose of this publication is to help landowners and tenants develop equitable cash lease agreements.

Determining a Fair Rent

Several methods of determining a fair cash rental rate are discussed in this fact sheet. You may want to estimate the rental charge implied by each of these methods, compare the results, and negotiate the final rental charge. Regardless of the approach used, some bargaining between the parties is generally necessary to tailor the agreement to the individual situation.

The market approach is best used as a starting point for negotiations. With the market approach, the going cash rental rate for your area is used as a guideline. Although this method appears simple on the surface, many questions must be answered: What land in your area is of the same quality with respect to productivity? How much is your neighbor actually paying his or her landlord? If this land is of superior quality, how much more is the additional quality worth?

A second approach is to calculate the cost of land ownership and add an appropriate return on equity (Worksheet 1). Land ownership costs include: 1) property taxes on the land; 2) repairs, depreciation, taxes, and insurance on any improvements on the land which are used by the tenant in the farming operation; and 3) a suitable return on the landowner’s investment. The return may be the opportunity cost of money invested in the land if it is debt-free, or the rate of return may be the interest rate on debt outstanding on the loan secured by the land. The land’s value for farming purposes should be used in these calculations. The value of the land for other development purposes is irrelevant if it is to be used for agriculture. If a tenant does not use the improvements on the land, they should be excluded from the cost of ownership calculation to avoid an unrealistically high rental fee.

A third approach, the residual income method (Worksheet 2), estimates the fair cash rent using the tenant’s expected net return. Expected total returns is the sum of expected price times yield plus other crop income such as wheat pasture rental or government program payments. The time period for the life of the agreement should be considered when estimating prices. The tenant’s total costs are: 1) variable production expenses such as seed, fertilizer, planting, and harvest costs; 2) fixed production expenses including depreciation, taxes, and insurance and interest on equipment and machinery investments; 3) return to management and labor.1 The expected net return (income less total costs and the return to management and labor) is the maximum rent that the tenant can afford to pay.

A fourth method of estimating a cash rental charge is to convert a crop share arrangement to a cash basis (Worksheet 3). Costs and returns are estimated to determine how much the landlord would receive under a share arrangement. The parties must agree on average prices and yields and the landlord’s share of any operating inputs such as fertilizer, chemicals, or harvest costs. Again, consider the length of the lease when determining prices. Fixed costs on land such as taxes that the landowner will continue to pay should not be included in the calculation. Returns are multiplied by the share a landowner would receive. Costs are multiplied by the share a landowner would contribute. Not all items listed on the worksheet are distributed between the two parties in all share agreements. Complete only the lines which are norms in the area or the parties feel should be shared. The cash figure arrived at under this method may be reduced to reflect the increase in risk borne by the tenant under a cash arrangement (5 to 15 percent is a common discount factor).

The tenant and the landlord may want to estimate cash rents using more than one method, compare the results, and negotiate a final figure. By using several different methods, the parties have a chance to see a range of estimated rents, reflecting different points of view. Careful negotiations will provide a balanced agreement that encourages honesty and cooperation among the parties.

Example Calculations

The example farm used in illustrating the different methods of determining a fair rental charge is a quarter section of land (160 acres) valued at $900 per acre2 used primarily for dryland wheat production. This tract is free of debt and has a hay storage barn that is used only by the owner. Average cash rent for comparable land in the area is around $33/acre. The tenant has $90,000 of machinery and equipment with an average expected life of 8 years and a total salvage value of $10,000. The equipment consists of a 140 hp tractor and various implements. The operator farms three other quarter sections of land (480 acres) outside of this agreement. The operator supplies 100 hours of labor valued at $10.00 per hour and a hired hand supplies another 100 hours of labor valued at $9.00 an hour.

Market Approach

Assume average cash rent for comparable land in the area is $33 per acre. A soil sample taken from the leased property reveals the land needs fertilizer applied at a slightly greater than normal rate due to low nitrogen quantity. The parties estimate the extra cost to be $4/acre.

Market rate per acre: $33.00

– Extra fertilizer cost per acre: -4.00

= Rental charge per acre: $29.00

Landlord’s Ownership Costs and Return to Equity

Although the land under this agreement has an improvement (the hay barn) costs associated with the barn are not included because it provides no benefit to the tenant.

- Property taxes on land = $2 (A)

- Improvements:

- Repairs and Maintenance = $0 (B)

- Property taxes = $0 (C)

- Insurance = $0 (D)

- Depreciation = $2 (E)

- Landlord's total cost per acre=

(A) + (B) + (C) + (D) + (E) = $2 (F) - Landlord's desired return on equity:

= Land value per acre x rate of return

= $ 900 x 4% = $36 (G) - Per acre cash rental rate = (F) + (G) = $38

Residual Income Method

The tenant’s expected net return is calculated by developing an enterprise budget for the leased acreage. Equipment and machinery costs should be divided among the total acres farmed by the tenant (owned and leased). In this example, the total equipment and machinery fixed costs are divided by four as the tenant farms a total of four quarters, only one of which is leased through this agreement. Management is usually valued as a percentage of gross receipts (excluding government payments). A charge of 5 to 8 percent is the standard range.

Returns:

- Grain receipts (160 a x 30 bu/a x $6.00/bu) = $28,800

- Government program payments3 —

- Other income (wheat pasture, $32/a) = 5,120

- Total returns = $33,920

Variable costs: (160 acres)

- Seed (2 bu/a x $16.00/bu): 5,120

- Fertilizer ($34.00/a): 5,440

- Chemicals ($4.70/a): 752

- Fuel, lube, & repairs ($44.80/a): 7,168

- Crop insurance ($7/a): 1,120

- Custom work (fertilizer application) ($4.00/a): 640

- Harvest costs

- Custom harvest ($16/a + $0.16/bu > 20 bu yield): 2,816

- Custom haul ($0.16/bu x 30 bu): 768

- Operating interest: 420

- Management: ($33,920 x 6.5%) : 2,205

- Labor

- Operator (100 hrs x $10.00/hr): 1,000

- Hired (100 hrs x $9.00/hr): 900

- Total variable costs: $28,349

Fixed costs:

- Equipment and machinery

- Depreciation4: ($90,000 – $10,000)/8 x 1/4: 2,500

- Interest5: [($90,000 + $10,000)/2] x 6% x 1/4: 750

- Taxes and insurance: 100

- Total fixed costs: $3,350

Expected net return =$33,920 – $28,349 – $3,350 = $2,221

Expected net return/acre = ($2,221/160 a) = $13.88

Converting Crop Share to Cash Basis

Assume in our example that a 1/3 to 2/3 share arrangement is common. The norms of the area require the landowner to pay 1/3 of fertilizer, chemicals, and application expenses. Cost and returns estimates are the same as those listed in the residual income method above. Only those costs and returns shared by the landlord are relevant in this calculation.

Table 1. Converting Crop Share to Cash Basis

| Total Returns | x Landlord Share | =Cash Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Returns: | |||

| Grain receipts | $28,800 | 1/3 | $9,600 |

| Government program payments | - | - | - |

| Other income (wheat pasture) | 5070 | 1/3 | 1690 |

| Landlord returns | $11,290 | ||

| Variable cost: | |||

| Fertilizer | 5,440 | 1/3 | 1,813 |

| Chemicals | 752 | 1/3 | 250 |

| Fertilizer applications | 640 | 1/3 | 213 |

| Landlord variable cost | 2,276 | ||

| Landlord expected net return = (total returns - variable cost ) | $9,014 | ||

| Expected net return / acre: ($9,014/160) | $56.34 | ||

| Less Adjusted for reduced risk (10%) | $5.63 | ||

| Cash rental rate | $50.71 |

The parties to the agreement now have four different figures to compare and use to negotiate the rental charge.

- Market approach: $29.00

- Landlord’s ownership cost and return to equity: $38.00

- Residual income method: $13.88

- Converting crop share to cash basis: $50.71

Adding Flexibility to Your Cash Agreement

A fair rental agreement must be reviewed and adjusted regularly to remain equitable. Changes in prices, costs, and yields can make a fair agreement lopsided in a short period of time. For instance, much higher fertilizer and fuel costs in recent years have led to larger shares for landlords in some cases. A flexible cash arrangement can reduce the frequency of necessary adjustments and distribute more of the risk between the parties.

However, flexibility does change some of the risks and opportunities faced by the parties. Adding flexibility for price and yield risks shifts more risk to the landowner, but will allow him or her to reap the advantages of “good years.” In accordance, the tenant will face less risk, but lose some of the benefits of exceptional price and/or yield years. Parties should keep this in mind before adding flexibility to their agreement.

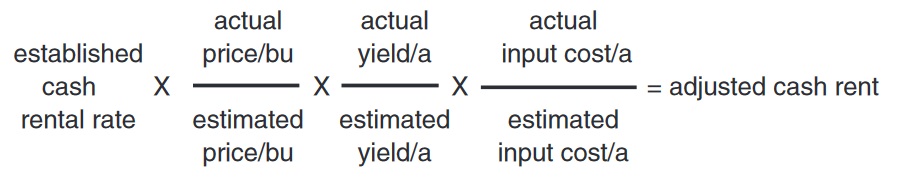

To adjust the rent figure arrived at by the residual income or crop share to cash methods, use the following formula:

- established cash rental rate x actual price/bu estimated price/bu x actual yield/a estimated yield/a = adjusted cash rent

Actual prices and yields are those realized at the end of the crop year, and estimated prices and yields are those used in establishing the agreement. If the parties wish to adjust for only price or only yields, the unwanted adjustment can be dropped out of the formula. Estimated prices and yields should be part of the farm lease agreement.

Suppose a land owner and tenant agreed on a rental rate of $32/acre with a provision to adjust the rent owed at the end of the year using actual yields and prices received. The original agreement was based on an estimated yield of 30 bu/acre and an estimated price of $5.00 per bushel. Actual yields were 25 bu/acre and actual prices were $5.50 per bushel The adjusted rental rate for actual prices and yields is:

$32 x ($5.50/bu) x (25 bu/a) = $29.33/acre

($5.00/bu) (30 bu/a)

The adjusted rental rate in this case is lower than the base rate. If the rent had been prepaid, the landlord would be required to reimburse the tenant for the difference ($32.00-29.33 = $2.67 per acre). Procedures for establishing the actual price should be stated in the lease agreement. See Table 1 for example calculations for alternative yields and prices.

Flexibility can also be added to cash rental rates arrived at by either the market approach and/or the landlord’s ownership cost approach. The first step is to develop yield and price estimates. For example, the $32 rent figure divided by an estimated price of $5.00 per bushel implies the landowner would receive 6.4 bushels. Next, the percentage of total yield the landowner receives is determined. The 6.4 bushels owed the landowner divided by the expected or average 30 bushel total yield indicates 21.3% of the total crop is received by the landowner. The actual production figures at the end of the year can be applied to adjust the rent figure. In our example, the landowner would receive:

25 bu x 21.3% x $5.00/bu = $26.63/acre

Taking it one step further, we can adjust the rental rate according to price, yield, and input cost. Suppose the landlord and tenant agreed upon $32/acre cash rent with price, yield, and input cost flexibility. This would account for any substantial changes in input cost during the life of the lease. For our example, we show a 10% increase in input cost along with the price and yield variation from earlier examples. To adjust the agreed upon rent figure, use the following formula:

$32 X ($5.50/bu)÷($5.00/bu) X (25 bu/a)÷(30 bu/a) X (217.91/a)÷(198.1/a) = $32.27/a

The enterprise budget software (agecon.okstate.edu/budgets) is a useful tool for determining expected returns per acre for both owned and rented land. Users can change input costs, yields, and prices received to see the affordable range of leasing costs the enterprise can support. Also, the enterprise budget software can toggle between ca

Table 2. Price & Yield Flexible Cash Lease Agreement Sensitivity Table.

| Price ($/bu) | Yield (bu/a) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 25 | 30 | 35 | 40 | 45 | |

| 7 | 29.87 | 37.33 | 44.8 | 52.27 | 59.73 | 67.2 |

| 6.5 | 27.73 | 34.67 | 41.6 | 48.53 | 55.47 | 62.4 |

| 5.5 | 23.47 | 29.33 | 35.2 | 41.07 | 46.93 | 52.8 |

| 5 | 21.33 | 26.67 | 32 | 37.33 | 42.67 | 48 |

| 4.5 | 19.2 | 24 | 28.8 | 33.6 | 38.4 | 43.2 |

| 4 | 17.07 | 21.33 | 25.6 | 29.87 | 34.13 | 38.4 |

Agreed upon $32/acre with a provision to adjust the rent owned at the end of the year using actual prices and yields.

Putting the Agreement in Writing

Once a tenant and landowner have decided on an equitable agreement, it should be put in writing. Some of the advantages of a written agreement are:

- It encourages emphasis of details and assures a better understanding by both parties.

- It serves as a reminder of the terms originally agreed upon and is valuable when the agreement needs to be evaluated and/or reviewed.

- It provides a valuable guide for the heirs if either the tenant or landowner dies.

In addition to the payment to be made, every written lease should include certain items: the names and addresses of the parties involved, a legal description of the property, number of acres, reservations of rights by the landlord, length of lease and renewal options, and signatures and acknowledgments of landlord and tenant. Signatures of witnesses and/or acknowledgement of recording may also be required.

Summary and Conclusions

Cash leasing agreements have advantages and disadvantages to both landowners and tenants. Both parties need to recognize the risks and opportunities they face under a cash agreement. By working together to determine a fair rental charge, the parties will have a greater understanding of each other’s position. This understanding should lead to better landowner and tenant relations and keep the agreement fair to both parties.

Arriving at a fair agreement is more likely if several of the methods discussed above are used in negotiating the final rental charge. Each method views the agreement from a different perspective and further clarifies each party’s position. Adding flexibility to an agreement is an easy way to ensure that agreement stays equitable.

The Cash Lease

Advantages to landowner:

- More stable income as price and yield risk are eliminated. Income can be scheduled for any time of the year.

- Requires less managerial input, thus reducing the worry of production and marketing decisions and the possibility of conflict with the tenant.

- Eliminates or greatly reduces cash expenditures.

Disadvantages to landowner:

- Can easily become inequitable due to changes in prices, costs, and technology.

- Fewer opportunities for income tax management.

- Will not realize benefits of good price and/or yield years if the agreement is not flexible.

- A greater chance of the farm being exploited through the depletion of soils or neglect of improvements.

Advantages to tenant:

- Total managerial freedom, lessening the chances of conflict over decisions with landowner.

- Receive all the benefits of “good years” and superior management.

- Eliminates time and effort associated with dividing crops and input purchases and the related record keeping.

Disadvantages to tenant:

- Must shoulder all the price and yield risk if the agreement lacks flexibility.

- Large capital requirements for inputs.

- May be required to pay part of the rent early in the year before the crop is planted.

- Landowners may request a higher rent due to above average yields even though these yields are attributable to above average management.

Additional Information

AGEC-198 Negotiation Strategies

CR-216 Oklahoma Pasture Rental Rates

CR-230 Oklahoma Cropland Rental Rates

Damona Doye

Extension Economist

Randy True

Extension Assistant