White-tailed Deer Harvest Management for Hunters and Managers

Introduction

White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) is the most popular big game species hunted in the United States, and thousands of hunters pursue deer annually in Oklahoma alone. Many hunters are aware that deer hunting in Oklahoma generates millions of dollars each year through license sales and excise tax dollars on hunting equipment to directly support wildlife conservation. However, many deer hunters do not recognize they directly play an important role in deer herd management every time they harvest (or choose not to harvest) a deer.

At a broad scale, deer populations are managed by state agencies, such as the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation. State agencies allocate permits and tags and can also shorten or lengthen hunting seasons to increase or decrease harvest. However, harvest ultimately comes down to the individual hunter. For landowners and lessees, pulling the trigger or releasing an arrow is one of the most important management decisions they can make to shape deer numbers and age structure.

Figure 1. Deciding which deer to harvest (and not harvest) is an important decision for landowners and managers.

Management Objectives

Deer managers should first consider property objectives when planning their harvest. The goals and objectives for the overall property and deer management specifically should be evaluated, as many harvest management decisions are based on landowner goals. Specific considerations include:

- Which deer management strategy (traditional, quality, trophy) is being used?

- How important is deer hunting and management to the overall property?

- Can deer populations negatively influence other aspects of the property(e.g., crop damage)

- What level of deer harvest can be achieved with the current number of hunters?

- What level of deer harvest is allowed by current hunting regulations?

Figure 2. Properties with extensive crop damage from deer generally require doe harvest to reduce density.

Deer Management Strategies

There are three primary deer management strategies commonly implemented by landowners. Traditional deer management is the least intensive and typically involves landowners taking any legal buck. Some landowners may choose to harvest does, but it is uncommon for intensive doe harvest to be implemented, as most use traditional deer management to maximize the number of bucks available for harvest without regard for age. The most common deer management strategy currently implemented on private lands is quality deer management (QDM). Under QDM, most landowners are interested in producing bucks that are 3.5–5.5 years old, with the exact target age class varying by site. QDM also involves the harvest of does, with the goal of maintaining the population at or slightly below carrying capacity (based on forage availability). Trophy deer management (TDM) is the most intensive form of deer management commonly practiced by landowners. Managers practicing TDM are interested in producing the largest-antlered bucks possible, so large-antlered bucks are only harvested when they reach full maturity at 5.5 or 6.5 years old. Under the TDM management philosophy on some properties, smaller-antlered bucks are harvested at younger ages to increase resource availability for larger bucks. Additionally, doe harvest is increased to keep deer density below carrying capacity to maximize available nutrition.

Figure 3. Deer populations are increased and decreased primarily by adjusting the number of does being harvested.

Doe Harvest

Deer population growth is primarily regulated by doe survival, and relatively small changes to doe survival can create large changes in population growth rates. Buck survival has limited effects on population size, as an individual buck can breed with many does. Deer population size can change following decreases or increases in fawn survival, but in most populations, fawn survival is not sufficiently low to be the most important factor in population growth. If landowners aim to maintain or reduce populations, harvesting does can help achieve these goals and lead to additional venison in the freezer as an added benefit of their management efforts.

How Many Does Should I Harvest?

Deciding how many does to harvest each year on a property is an important management question that can be somewhat difficult to precisely determine. It can vary widely depending on local site characteristics and current deer density. In most places, harvesting about 30% of adult does results in a stable population. Taking more than 30% generally results in a decrease in the population, whereas taking less than 30% usually increases the population. However, estimating an exact number of deer using a property may not be realistic. Trail camera surveys conducted the same way each year can provide an index of population size to track over time but generally should not be used to estimate density. Thus, doe harvest goals are best approached as a moving target, adjusted each year based on habitat conditions.

Determining an appropriate number of does to harvest begins by evaluating forage availability relative to deer numbers. On properties with food plots, simply placing an exclusion cage in each food plot is a great starting point to evaluate deer numbers. Exclusion cages protect forage from grazing by deer, and the difference between the inside and outside of the cage represents for-age consumption. Some difference between the caged and uncaged portion is desirable, as it shows deer are using and benefitting from the plot. However, if forages within cages are much taller than those outside of cages (see figure 4), especially on larger (>1 acre) food plots, forage is likely limiting to deer on your property. In native plant communities, consider what native forages deer are commonly eating. If deer are creating browse lines or commonly eating poorly selected foods such as sweetgum (Liquidambar styracifua) leaves, there is likely a problem. Similarly, consider how highly selected forages such as greenbriar (Smilax spp.) are being used by deer, as extremely heavy browse pressure can indicate a reduction in deer density is needed. Increasing availability of native forages, creating additional food plot acreage and harvesting more does can help alleviate forage limitations.

Figure 4. Lip-high forage outside of exclusion cages is an obvious indicator something needs to be done! This relatively large warm season food plot is planted in a mixture of cowpeas (Vigna unguicula-ta) and jointvetch (Aeschynomene americana). Deer have heavily overgrazed this plot, which has nearly eliminated cowpeas from the feld and left only short, overgrazed jointvetch.

On properties where maintaining current deer density is desirable, a good starting point for managers where rainfall is generally not a major limitation (i.e., greater than ~30 inches per year) is harvesting approximately one doe per 80 acres. This assumes typical survival and recruitment with a population of approximately 50 deer per 640 acres (or 50 deer per square mile). It is intended as a starting point rather than a set rule. To decrease the population, you might target harvesting one doe per 40 acres. Doe harvest could be limited to one doe per 120 acres (or less) to increase the population slowly over time. If you suspect fawn recruitment is severely limited by predation or doe survival is reduced by disease, it may be worthwhile to reduce doe harvest. Obviously, this target may change depending on how many does your neighbors are taking. If your neighbors implement aggressive doe harvest, you likely will not need to take as many from your property. Conversely, if your neighbors do not hunt or only shoot bucks, you will probably need to increase your harvest rate to account for does not being harvested on their property. The landscape context matters, especially if you own or manage smaller acreage (i.e., less than ~500 acres).

The best approach to doe harvest for most landowners is to set a goal based on whether they want to grow, maintain or decrease the population, and then adjust harvest goals over time. Hunter observations and trail camera surveys can provide relative abundance indices. Forage use in food plots and native plant communities also can be useful to evaluate deer numbers relative to food. Finally, harvest data such as body weight and kidney fat index can be used to measure herd health. All these data streams are useful to determine whether harvest should be increased, decreased or maintained, which highlights the importance of keeping good management records.

Figure 5. Red maple (Acer rubrum) is a moderately selected deer forage. However, heavy use of woody plants during the growing season likely is a sign that high-quality forage availability may be limited.

What About Properties in Semiarid Regions?

Deer occur in a variety of vegetation communities across Oklahoma, including semiarid locations in the western portion of the state. Management to produce robust populations with large-antlered bucks is possible in arid areas, but there are several differences in monitoring and developing harvest prescriptions where rainfall is limited. For example, evaluating food availability relative to deer density should be approached with caution in semiarid regions. Drought makes it more difficult to evaluate forage availability consistently over time, as deer often eat plants during drought that they might not otherwise select. Similarly, antler size and body weight of deer will vary based on precipitation, with smaller antler sizes and weights during dry years. Drought cycles also tend to regulate deer populations, as fawn production increases and decreases with rainfall amounts. On properties in semiarid regions, it is best to approach doe harvest conservatively, especially during dry years when fawn production is reduced. Harvesting doe fawns can be an effective approach in these locations to manage deer density without removing more productive adult does from the population. Doe harvest still can (and often should) be used to manage these populations, but the population will take longer to rebuild if overharvested compared to populations in areas with consistent rainfall. An excellent resource on deer management in semiarid locations is “Advanced White-Tailed Deer Management: The Nutrition-Population Density Sweet Spot” by Timothy Fulbright, Charles DeYoung, David Hewitt and Don Draeger.

Which Does Should I Harvest?

Harvest decisions require several considerations, but the most important thing to remember is that harvest numbers are far more important than which specific does are taken. If you have not hit your doe harvest goal and are presented with an ethical shot, you should not pass up the opportunity. However, if multiple does are present in a group, you may consider the age of each doe and whether she has fawns in your harvest decision.

Older does tend to produce a greater number of fawns than yearling does. Thus, adult does may be desirable to harvest if you are trying to significantly reduce the population. Doe fawns and yearlings are a good choice to harvest if you are trying to grow the population but would still like to take a doe or two. If you are trying to maintain the current population, taking a mixture of doe age classes can be a good approach.

Deer season regulations in most states are set to allow doe harvest after fawns are weaned, which takes place about 70 days after birth. Unless a fawn is relatively small with very distinct spots to indicate it was born later in the year, having a fawn in tow should not stop you from harvesting a doe, but it could be used to inform your decision. Some does are inherently better mothers, as does that successfully raise a fawn in one year are more likely to be successful the following year. If you are trying to grow the population, it may be wise to target does that do not have fawns. Lone does are unlikely to be “dry” or infertile, but they probably were not as successful at hiding or defending their fawns from predators. Conversely, taking does with fawns is a good approach if you are trying to reduce deer density.

Does accompanied by one or more buck fawns may be good candidates for harvest when the opportunity arises. The majority of yearling bucks disperse each year, and much of this dispersal is likely related to aggressive behavior from their mother around the time the fawn turns one year old. Buck fawns from does that were harvested during the fall are less likely to disperse compared to those that remain with their mother through the winter. Buck dispersal is not a problem for the population, as new bucks from the surrounding area will also disperse onto your property. However, if you are implementing intensive habitat management practices to increase forage availability, buck fawns born to does living on your property are valuable, as they have benefitted from generational effects of good nutrition. Long-term changes to deer antler and body size are greater with consistent, high-quality nutrition over several generations that may not be available to fawns born farther away from your property. It is not worth specifically targeting does with buck fawns, but it certainly will not hurt your management program to retain a few additional bucks that were born on your property.

Doe harvest should not be viewed as a one-time event but rather as a consistent effort that requires monitoring and changes over time. Deer populations can grow surprisingly fast, especially on smaller properties where surrounding landowners are not harvesting many does. Be sure to keep track of harvest records over time and adjust goals as needed to maintain the population at a desirable level.

Figure 6. Buck fawns are less likely to disperse if their mother is harvested, which may be a consideration for evaluating which doe to harvest.

When Should I Harvest Does?

Timing of doe harvest is a common consideration for deer hunters. Many hunters are concerned about harvesting does before or during the breeding season, as they do not want to hurt their chances of seeing a buck. However, there are several reasons harvesting does early in the season may be desirable.

Doe harvest early in the season increases the chances of meeting harvest goals. Hunters who choose to wait until December to take does often are faced with more educated deer that have responded to hunting pressure. This often makes hunters less likely to reach their harvest goal, especially when you consider the relatively short time left in the hunting season after the rut.

Early doe harvest makes sense biologically for several reasons. First, it reduces deer numbers prior to forage limitations later in the season, which reduces competition for limited forage. Heavy foraging pressure on food plots and native plants can be reduced by taking does early in the season, which leads to better forage production. Additionally, reducing doe numbers prior to the rut can result in increased breeding competition between bucks and more exciting hunting. Finally, it is easier to distinguish between does and buck fawns earlier in the year. Mistakes become more likely when harvesting does in December and January when does and buck fawns are more similar in body size. Harvesting some buck fawns by accident is not a problem, but harvest decisions are easier to make early in the season. There is no problem harvesting does throughout the hunting season. However, we do not recommend waiting until the very end of the season to implement doe harvest on a property. Taking clean, ethical shots and trying to harvest multiple does in a hunt (where legal) when the opportunity is given are better approaches to minimize hunting pressure, compared to forgoing early season doe harvest.

Figure 7. When trying to reduce deer numbers, taking multiple does in a hunt is an excellent approach to minimize hunting pressure.

Buck Harvest

Setting buck harvest restrictions differs from determining doe harvest goals in several ways. First, buck harvest often is most strongly related to hunter objectives, whereas doe harvest usually considers deer density related to forage availability and other factors such as crop depredation. Second, the age of bucks being harvested generally is much more important than age of harvested does. Finally, buck harvest has little effect on population growth rate or density despite being very important to hunters. This section will focus primarily on evaluating which bucks to target based on objectives rather than how many can be taken, as bucks are generally not a limiting factor to deer population growth.

Which Buck Should I Harvest?

Even the smallest yearling buck is capable of successfully breeding does. Thus, which bucks a hunter or manager chooses to target is based primarily on objectives rather than concern about the population. Under traditional deer management, a hunter likely would choose to take the first buck that presents a clean shot opportunity. Most hunters now practice some form of QDM or TDM, which requires greater selectivity in buck harvest.

Under QDM, hunters generally choose to harvest males that are at least 3.5 or 4.5 years old. Which age class to target as a minimum depends on property size, neighborhood hunting pressure and willingness to pass bucks. Bucks reach their full antler potential at approximately 5.5 years old. The antlers of a 3.5-year-old buck are approximately 68% of their full potential, but this increases to about 92% of their full potential when they reach 4.5 years old.

Targeting bucks at 4.5 years old often is considered a good balance between hunting opportunity and allowing deer to grow larger antlers, especially on properties where 3.5-year-old bucks are relatively common. In some areas with heavy hunting pressure, it may be uncommon for a buck to reach 4.5 years old, so hunters in those areas may choose to harvest some bucks at 3.5 years old. There is nothing wrong with either decision, and some bucks will slip through to older age classes with either age target. It is important to recognize that harvesting bucks at 3.5 years old will limit the maximum antler size a property is likely to produce.

Managers practicing TDM generally allow bucks to reach their full potential at 5.5 years old. This requires quite a bit of patience and recordkeeping to track individual bucks over time. However, there is no other way to ensure bucks are producing the largest antlers their genetics and nutrition will grow. If you are considering practicing TDM, it is important to be realistic about your expectations with regard to property size, as neighbors with different objectives can strongly influence your results.

Deer management cooperatives are one approach to successfully implement QDM and TDM. For hunters and managers working in landscapes with smaller property sizes, cooperatives allow neighbors to work together to reach common objectives. Cooperatives can be formal or informal, and they typically involve neighbors meeting to establish common objectives for buck and doe harvest. Through honest communication, deer management cooperatives help reduce the likelihood of having to use (or hear) the common excuse — “if I didn’t shoot him, my neighbor would have.”

Figure 8. Evaluating which buck to harvest should be based on realistic property management objectives.

High Grading

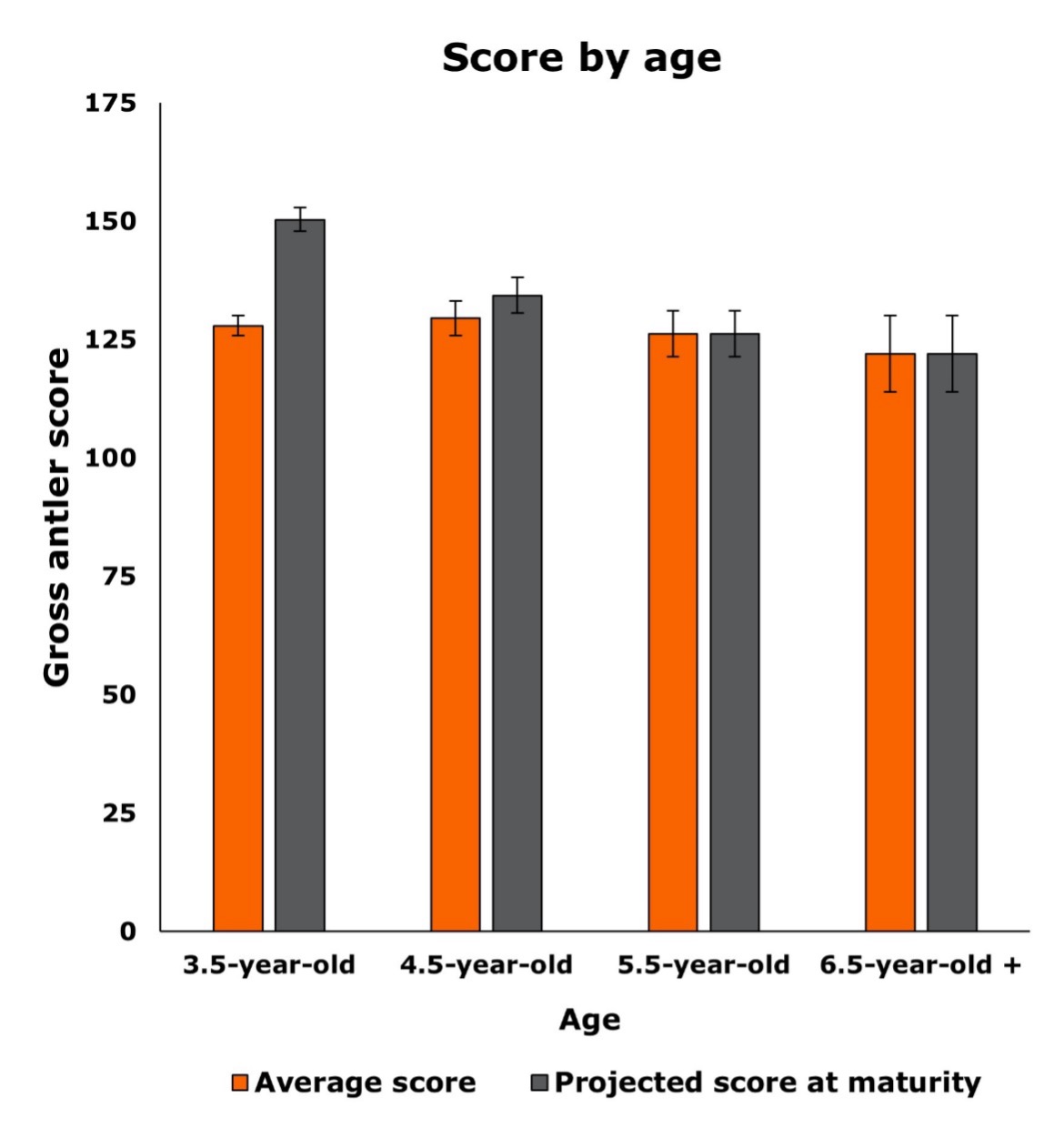

One important factor that is overlooked by nearly every deer manager is high grading. High grading is a term that is often used by foresters to describe a timber harvest that removes the best, larger, more valuable trees and leaves the smaller, less valuable trees. A very similar scenario occurs with deer management, where the bucks with the largest antler potential are commonly harvested at 3.5 years old. Antlers follow a predictable growth curve, and bucks that are larger than average at young ages will likely also be larger than average when they are older. Under high grading, the bucks that make it to 4.5 years old on average have lower potential (because they were not taken as large antlered 3.5-year-olds), and only bucks with the lowest average antler potential make it to 5.5 years old. In most cases, this is evident when harvested 3.5-year-old bucks have similar antler sizes to 4.5- and 5.5-year-old bucks. Ever wonder why nearly every buck on your property has a 120–130-inch rack? It is probably related to high grading!

Figure 9. This graph of landowner harvest data is an example of high grading based on the average score of 3.5-, 4.5-, 5.5-and 6.5+ -year-old bucks. The orange bars represent the average gross Boone and Crockett score at harvest by age class. The grey bars represent the average score if each buck had been allowed to live to 5.5 years old. Notice how the size of bucks across age classes does not differ much, but the bucks being harvested at 3.5 years old had the greatest average potential antler size. On this property, the 3.5-year-old bucks averaged 128 inches but would have averaged 150 inches had they reached maturity.

The solution to high grading is relatively simple: harvest deer by age, not antler size. If you wish to harvest deer at 3.5 years old, do not specifically target the best 3.5-year-old bucks on your property. Instead, plan to take the first buck you believe to be 3.5 years old that presents an ethical shot. The same can be said for those targeting 4.5- or 5.5-year-old bucks. Simply allowing the largest-antlered deer within an age class to advance to the next age class will reduce problems associated with high grading.

For those with relatively large properties, it is possible to manage buck harvest through low grading. Instead of taking the best bucks at 3.5-years old, hunters can take the smallest males in younger age classes to reduce competition for forage and other resources. Care should be taken if this approach is pursued, as it would be better to allow some smaller bucks at a given age to advance to older age classes than to accidentally harvest an exceptional 2.5-year-old buck. If you are interested in pursuing this approach, an excellent resource is the book “Strategic Harvest System: How to Break Through the Buck Management Glass Ceiling” by deer researchers Dr. Steve Demarais and Dr. Bronson Strickland.

An important caveat to buck harvest strategy is that buck management has little effect on the genetics of a deer herd. Genetic management through culling has been extensively researched, and even when conducted intensively it has little effect on the genetics of the herd. Similarly, high grading or low grading can change the observed antler size (i.e., phenotype) but there will be minimal changes to deer genetics. In many ways, our inability to alter genetics in free-ranging deer should be viewed as a good thing! Deer population genetics are robust to selective harvesting, which provides managers with forgiveness when mistakes happen with buck harvest.

Figure 10. Selectively harvesting young bucks with relatively large antlers can result in high grading. This main-frame 11 point is likely several years from producing his largest set of antlers.

Aging Deer on the Hoof

Age estimation of bucks on the hoof is based on body characteristics such as apparent leg length, chest girth and neck thickness. Although far from a perfect method, aging on the hoof can be used to guide harvest decisions, especially when applied conservatively by placing borderline deer into younger age classes. Additionally, keeping records of individual bucks from trail camera images from year to year can increase aging accuracy. Even if some bucks are harvested mistakenly because of aging errors, this method is still preferable to antler-based metrics because it reduces the chances of high grading.

Figure 11. Antler point restrictions can protect most 1.5-year-old bucks, but they are not effective at protecting older age classes because many bucks have eight or more points at 2.5-years of age.

Antler Restrictions

Many hunting clubs have difficulty in developing and enforcing age-based buck harvest criteria and instead rely on antler restrictions. Antler restrictions can be useful to protect younger age classes of deer, but care should be taken when selecting antler restrictions to minimize high grading.

Antler point restrictions allow the harvest of bucks with a minimum number of points on one or both antlers. These are the least-desirable antler restrictions, as they generally do not protect all young bucks and often do not allow for some older bucks to be taken. For example, a four point per side rule allows the best 1.5-year-old bucks to be taken while preventing hunters from harvesting a fully mature buck with three points on each side. Although this may be a useful rule for some clubs or public hunting areas, it certainly does not work well for those practicing QDM or TDM. At the worst, it can result in severe high grading without allowing for the harvest of many smaller antlered bucks when relatively strict point restrictions (such as nine or ten total points) are in place.

Antler restrictions based on inside spread or main beam length are much more effective than point restrictions. It is best to consider both spread and beam length restrictions together and allow harvest of bucks that meet either minimum. Spread restrictions are easier for most hunters to evaluate, but some bucks that have a relatively narrow frame could be eligible for harvest under a beam length but not antler spread restriction.

It is important to consider local antler size by age before implementing restrictions, as a good restriction allows most bucks that reach some minimum target age to be harvested while protecting younger bucks. Thus, restrictions need to be fairly localized to avoid being either too restrictive or not restrictive enough. Consulting with state agency staff on average antler size by age class can be helpful when evaluating antler restriction criteria.

When possible, combining relatively strict antler restrictions with an age-based criteria works well. This strategy should minimize high grading, while allowing hunters that are unsure of age estimation to harvest bucks that meet minimum antler criteria. This approach also allows hunters to take mature bucks with small antlers that would never be eligible for harvest under the antler restriction criteria. Few things frustrate most hunters more than forcing them to pass a mature buck that happens to have busted points, broken beams or relatively small/unique antlers.

Figure 12. This buck likely would never have been eligible for harvest on properties with a four-point on-a-side antler point restrictions despite being mature. Using spread, main beam length and age restrictions helps avoid this problem.

Disease and Harvest Management

Chronic Wasting Disease and Hemorrhagic Diseases are two of the most important deer diseases that should be considered when planning harvest management.

Chronict Wasting Disease

CWD is an always-fatal, transmissible spongiform encephalopathy that infects wild and captive cervids. Similar diseases include bovine spongiform encephalopathy (commonly known as mad cow disease) in cattle and scrapie in sheep. Deer infected with CWD commonly appear healthy because the incubation period (i.e., time from infection to showing clinical disease signs) is 18–24 months. Toward the end of the disease progression, a CWD-infected deer may look emaciated, uncoordinated and lose its fear of humans. Though live tests are in development and improving, the only definitive test currently available for diagnosing CWD is post-mortem.

Deer population dynamics are influenced by CWD in two primary ways. First, when deer herds have relatively high prevalence of CWD, their survival tends to decrease in a way that negatively influences population growth. Of course, CWD directly kills many infected deer, but additive mortality from other sources (including hunting) compounds this issue. Deer with CWD are more likely to be killed by vehicles, predators and hunters because of their decreased vigilance, which decreases survival at a faster rate than direct mortality from CWD alone. Second, decreased survival tends to result in a younger herd age structure, which can be a problem for managers interested in producing mature bucks for harvest.

If you are hunting in an area with CWD, you should have any deer you harvest tested for CWD. Additionally, you should be aware of state regulations regarding the movement of deer carcasses to avoid spreading CWD to new areas. The easiest way to follow these guidelines is to clean and debone deer on the property where they were harvested and then dispose of the carcass on site. In Oklahoma, it is currently illegal to bring in whole deer carcasses from outside into state (except when being transported directly to a licensed taxidermist), and only the following parts may be imported: antlers or antlers attached to clean skull plate or clean skulls, animal quarters containing no spinal materials or meat with all parts of the spinal column removed, cleaned teeth, finished taxidermy products and hides or tanned products. Consult with your state agency to ensure you follow appropriate regulations, as these rules may change and are an important step to slow the spread of CWD to new deer populations.

Potential population declines paired with younger buck age structure can certainly conflict with deer management objectives. Managers must consider adjusting their expectations, but hunting is an important part of CWD management. If CWD has not been detected in your area, taking steps to reduce deer density now can help slow prevalence if your area becomes CWD positive in the future. Managing for deer herds with moderate density within the bounds of available forage will provide benefits with or without future CWD concerns.

If your area currently has CWD, continuing to maintain moderate deer density likely will help slow disease spread. Unfortunately, buck harvest expectations will need to be adjusted, as CWD serves as an additional mortality source for older males. At low prevalence rates, it may still be possible to produce 5.5-year-old bucks, but this becomes increasingly difficult as prevalence rates increase. Most managers likely will need to shift their objectives to producing primarily 3.5-year-old bucks and attempting to harvest them at this age. At high prevalence rates, buck harvest age may even need to be reduced further. CWD is a complex issue for deer managers without any easy solutions, but deer hunting can (and should) continue with CWD, as long as expectations are realistic.

Hemorrhagic Diseases

Hemorrhagic Diseases are caused by two related viruses: Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease is caused by the EHD virus, and Bluetongue is caused by BT virus. Both EHD and BT are spread by biting midges in the Culicoides genus and cause similar clinical signs. Outbreaks of HD generally occur during late summer and early fall, and deer often are found dead near water sources.

In general, HD is less of a long-term problem for deer populations than CWD. Most HD outbreaks are relatively limited in spatial and temporal scale and have minor, relatively short-term population effects. However, adjustments to harvest after large HD outbreaks likely will help the population rebound. If you find large numbers of dead deer around water sources in late summer, it may be wise to decrease your doe harvest rates if the population is already at moderate density. This will vary depending on density and outbreak severity, as HD should not serve as an excuse to stop doe harvest if your area is overpopulated.

Figure 13. Deer that have died from hemorrhagic disease commonly are found in and around water in late summer.

Tracking Management Progress

Harvest Data

Deer harvest data provide important information to evaluate management progress that is relatively easy to collect. Unfortunately, many landowners and managers fail to collect harvest data. Developing a harvest data collection protocol ahead of each hunting season is an important step to ensure these data are collected from every harvested deer. At a minimum, hunters should record sex, age and weight (either whole or dressed) from all harvested deer.

Ages can be estimated from tooth replacement and wear or using cementum annuli analysis of the incisors. Neither age estimation technique is perfect, but they provide results that are useful to guide management. For does, considering the weights of fawns, yearlings (1.5-year-olds) and adults separately is ideal, and these age groups can be assigned using tooth replacement alone. Bucks exhibit greater changes in size with age, and it is best to evaluate weights and antlers by age class, although errors in age assignment should be considered. Thus, doe weights are likely the best metric for many landowners to track because age assignment is relatively simple and most properties harvest more does than bucks.

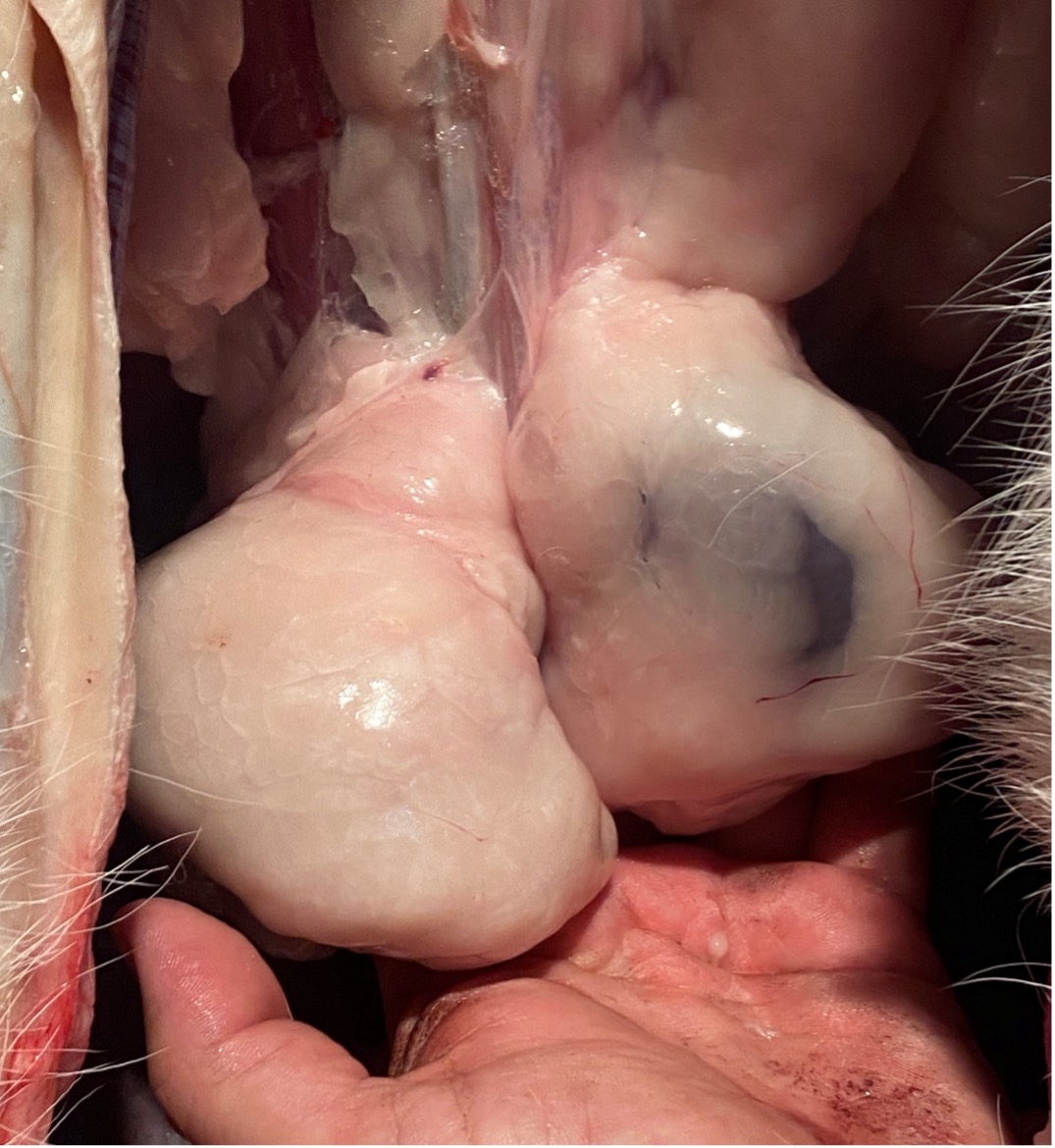

Additional data worth collecting include doe lactation rate and buck antler size. Doe lactation indicates that a doe successfully recruited at least one fawn into the fall population. The percentage of does that are lactating when har-vested can be used to track fawn recruitment over time. Given many properties are interested in producing larger-antlered bucks, gross Boone and Crockett score may be an important metric to collect. Antler score charts are available at B & C Score Chart PDF's. Managers that are unable to collect a full Boone and Crockett score from each deer can also can use a resource from the Mississippi State University Deer lab available at Estimating Boone & Crockett Score to estimate gross score using measures of antler mass, inside spread, main beam length, and number of points. For additional information on deer harvest data collection, check out the University of Tennessee Extension fact sheet at Collecting and Interpreting Deer Harvest Data for Better Deer Management.

Figure 14. On properties with ample food, deer should have greater fat reserves. Keeping track of the fat around the kidneys (seen here) by collecting Kidney Fat Index data can be useful to monitor deer body condition.

Figure 15. Collecting antler measurements from bucks can help managers track their management program’s progress over time.

Habitat Evaluation to Inform Harvest Decisions

In addition to tracking changes to deer body weight and antler size over time, it is important to evaluate habitat conditions when making doe harvest goals. Specifically, managers should consider whether forage availability is limited, especially during the late summer and winter stress periods. There are several metrics that indicate forage limitations, but three are relatively easy to consider.

First, managers should evaluate the plants they commonly see being browsed or grazed by deer. On most properties, many of the highly selected forages available during the growing season such as pokeweed (Phytolacca americana), old-field aster (Aster pilosus) and common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia) will be grazed. Similarly, species such as blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), elm (Ulmus spp.) and greenbriar are commonly browsed during the dormant season. However, if these species are either not present or show significant foraging pressure, forage is likely limited and increased doe harvest should be considered.

Signs of deer eating species that are not selected forages can also indicate a problem. For example, significant foraging on species such as sweetgum, eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana), or cool-season grasses such as orchardgrass (Dactylis glomerata) and tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea) are signs that forage is limiting. Deer will occasionally forage on a wide variety of plants, but signs of browsing or grazing pressure on species that are not selected forages are indicators that doe harvest should be increased.

Figure 16. Moderate deer grazing pressure on high-quality plants, such as this common ragweed, should be expected on most properties.

Food plots can provide additional information on deer forage availability relative to population density, but only if managers use exclusion cages to assess forage consumption. As mentioned previously in this publication, some difference in height of forages inside versus outside of cages is expected, but pay attention to dramatic differences in forage availability, especially on larger feeding plots. Keeping track of relative forage availability does not necessarily provide an exact number of does to harvest, but it provides information that can be used to adjust harvest rates up or down.

Conclusions

Deer harvest management is an important consideration for landowners and managers with deer hunting as a property objective. Managers should use their objectives, deer biology and common sense to guide their harvest decisions. Although harvest goals are a moving target, managers who consider the approach outlined in this fact sheet are likely to make well-informed decisions.

Figure 17. Some difference in height between grazed and ungrazed forage is expected. Here, deer are foraging on a perennial clover food plot but there is still is ample forage available, indicated by the clover inside the cage being only slightly taller than the clover outside the cage.

References

Advanced White-Tailed Deer Management: The Nutrition-Population Density Sweet Spot. T. E. Fulbright, C. A. DeYoung, D. G. Hewitt, and D. A. Draeger. https://www.tamupress.com/book/9781648430565/advanced-whitetailed-deer-management/

A Practical Guide to Food Plots in the Southern Great Plains. OSU Extension Factsheet E-1032. https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/a-practical-guide-to-food-plots-in-the-southern-great-plains.html

Chronic Wasting Disease. Oklahoma Department of Conservation. https://www.wildlifedepartment.com/hunting/resources/deer/cwd

Collecting and interpreting deer harvest data for better deer management. UT Extension Factsheet PB 1892. https://utia.tennessee.edu/publications/wp-content/uploads/sites/269/2023/10/PB1892.pdf

Strategic Harvest System: How to Break Through the Buck Management Glass Ceiling. S. Demarais and B. Strickland. https:// www.msudeer.msstate.edu/strategic-harvest-system.php

White-tailed Deer Habitat Evaluation and Management Guide. OSU Extension Factsheet E-979. https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/white-tailed-deer-habitat-evaluation-and-management-guide.html