Weaning and Management of Weanling Horses

Young, weaned horses below the age of one year are called weanlings. During this time of life, the foals have been separated from their dams, are rapidly growing and receiving training and management practices that have life-long effects. This Fact Sheet provides recommendations on preparing the foal to be weaned, weaning methods and care and management of the weanling horse. More information on growing horses can be found in Extension Fact Sheets ANSI-3985, “Foaling Management and Care of the Nursing Foal” and ANSI-3977, “Managing Young Horses For Sound Growth.”

Preweaning Care

In free-roaming or feral horses, foals are naturally weaned around eight to nine months of age, while most management systems will wean foals between 4 months and 6 months of age. Foals will spend the first 4 months to 5 months by their dam’s side, receiving nutrition from the mare’s milk. The foal’s nutritional requirement is met solely from the mare’s milk for the first several months. As the foal becomes larger, their nutrient needs exceed the nutrients available from the mare’s milk. Foals will begin eating small amounts of grain within weeks after birth. If given access to grain, most will consume substantial amounts by two to three months of age. Most foals will readily eat from the dam’s trough; however, to ensure access, many farms use creep feeders. Creep feeding, supplying a separate feed source to nursing foals, is especially important on farms that wean later than four months of age. By this age, the foal’s nutritional needs exceed what is available from their dam’s milk. In addition to the benefit of the added nutrition of creep feeding while still nursing, foals accustomed to eating grain will likely continue to eat through the weaning process and be less stressed during weaning.

Options for Feeding the Foal

Supplying the correct nutrients to the growing foal can be accomplished through a variety of options. Foals can be fed in a stall with a mare using commercial feeders. These feed-ers have adjustable slotted bars that allow the foal’s nose to fit through the feeder, but not the mares. Foals can be briefly separated from the mare while both eat their concentrate ration, but should remain in close proximity and visual contact. Foals also will eat out of the same feeder or trough as the mare. If allowing the foal to simply eat with the mare, it is important to ensure its nutrient needs are being met. Finally, creep feeders can be built in the environment that allow access to only the foal.

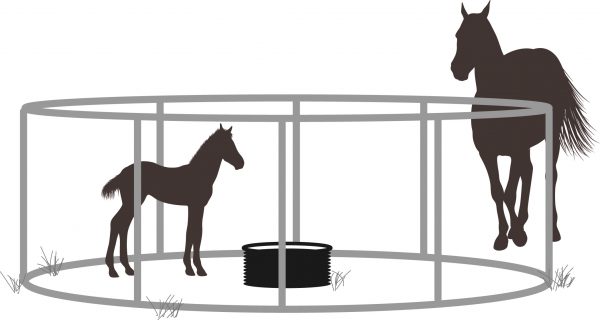

Creep Feeder Design

Creep feeders should be designed to allow for easy, safe entry and exit of foals while restricting access of mares to the creep feed. The height and width (around 4 feet tall and 2 feet wide for most light horse breeds) of the opening must restrict the entrance of mares to the feed source. Mares may spend large amounts of time trying to enter creep feeders, so sturdiness of construction is important. Some mares may be quite determined to reach the feed, and will even crawl through an opening, requiring manual extraction. The mare should not be able to reach feed by protruding their head and neck over or through openings, thus defeating the purpose of a creep feeder.

As foals characteristically will eat together, feeders must be large enough to accommodate several foals at one time. A 10-foot X 10-foot area should be sufficient for one or two foals; however, it might be too small for a larger number foals. Foals must be able to turn around easily while inside the feeder. Feeders that are too confining may increase foal stress and injury. Restricting visual contact to mares while the foals are inside the feeder may restrict feeder usage and increase foal injury. Also, multiple entry and exit points will reduce the chance that foals will become panicky because they did not have quick access to an exit.

Feed offered to supply only a 24-hour ration will reduce feed spoilage/wastage, and also minimize health risks associated with mares breaking into the feeder. Feeders must be cleaned routinely and soundness of construction checked.

Many types of creep feeders are available and the choice will depend on facility design, number of horses etc.

Stall feeders for foals are designed so that only the foals nose fits between the spacing bars, not the mares. Spaces between bars can typically be adjusted.

To encourage use, the location of the feeder should be near the mare’s feeding area, a water source or other areas visited frequently by mares and foals. This is especially important in large pastures.

At first, foals may need to be shown how to enter a feeder. One method for teaching foals is to place two or three inside for a few minutes and show them the feed. Usually, once foals identify the feed source with the creep feeder, they readily enter and exit without problems. Also, this practice will make “teachers” for the other foals.

Creep Rations

Foals generally eat small amounts very frequently. Intake of creep feed varies greatly between foals, and from one day to the next with the same foal. Foals may consume 1 pound to 5 pounds of creep feed per day. Providing smaller allotments during the day, such as when mares are fed, is more desirable than supplying large single feedings. Even though the capacity and appetite of foals of this age guards against overfeeding, large amounts left in creep feeders increase the chance of spoilage and desire of mares to gain access. Feed should be checked at least once daily and any wet or moldy feed should be replaced.

Creep feeds must contain a balanced amount of energy, protein, minerals and vitamins. Many commercially developed rations designed for weanlings will contain appropriate nutrient densities to be used also as a creep feed. A typical creep feed will supply approximately 1.4 Megacalories of digestible energy per pound (Mcal DE/lb) of feed. Creep feeds should contain 14% to 16% crude protein, about 0.8% calcium and 0.5% phosphorus to ensure a correct balance with this energy concentration. Commercially developed mixes will also contain additional minerals and vitamins.

The feed should be highly palatable and coarsely processed to enhance digestion; e.g. pelleted, extruded, rolled or crimped oats and cracked or steam-flaked corn. Pelleted and extruded creep feeds have the advantage of reducing the amount of sorting of individual ingredients.

Management and Health Programs

Following separation, the foal usually enters into increased contact with human handlers, with an increased need for behaviors that promote safety for the foal and human. The foal should be taught to accept basic handling and be comfortable and relaxed around humans before weaning. Haltering, brushing and leading the foal while still on the side of the mare will be helpful for later training.

Because weaning can be very stressful, the foal should be in good health before being separated from its dam. Several vaccinations are recommended to begin between 3 months to 6 months of age. For specific needs to be met, vaccination and deworming schedules need the supervision of a veterinarian that is familiar with your farm practices and location.

Weaning Systems

Time of Weaning

The choice of age for weaning foals depends on factors such as the health status of the mare and foal, temperament of the mare, the environment into which the foal will be weaned, maturity of the foal at a given age and the level of management on a given farm. If necessary, foals can be weaned as early as a few days post birth; however, the usual age for weaning is between 4 months and 6 months. Newborn foals rely on the mare for nutrition, protection and security. As such, foals weaned at extremely young ages require intense nutritional and behavioral management, and may not develop some of the natural behaviors associated with horses. By 4 months of age, however, the foal should be eating freely and becoming less dependent on its dam for protection and emotional sup-port. Weaning before this age may increase weaning stress, especially if environmental conditions are harsh, the foal is not eating grain or the foal is heavily dependent on the mare. Prolonging weaning until 6 months may result in a more robust foal with less social disturbance than foals weaned at an earlier age.

Many breeders prefer to separate a mare with adverse disposition or vices from her foal as soon as advisable. Behavioral tendencies in mares often are repeated in their offspring, however it is difficult to interpret whether this is a result of shared genetics or the environment the mare created for the foal. Some behavior patterns can be learned from the mare and with an earlier separation, the mare’s behavior may have less influence on the foal’s behavior. Conversely, calm mares that interact readily with humans tend to create foals with similar behavior patterns in their offspring. There are also substantial differences between individuals in the strength of the mare/foal bond, which may be necessary to consider in terms of time and method of weaning.

Weaning System

There are a variety of weaning methods utilized in the horse industry. The management level of the breeding farm, the condition and temperament of the mare and foal, facilities and the number of foals to be weaned during a given period of time will ultimately affect decisions on how foals are weaned. While long-term studies on different weaning methods and their effects on subsequent growth and development have not yet been performed, many studies have reported on the short-term behavioral and physiological response to weaning methods. Minimizing stress is critical, as stressed foals may be immunocompromised during this period and more susceptible to gastrointestinal and respiratory pathogens. Behavioral indicators of stress are increased vocalization, movement and loss of appetite. Physiological indicators such as increased heart rate and cortisol concentrations also accompany the stress of weaning.

Regardless of method, foals weaned together and those consuming feed prior to weaning will have less weaning stress.Weaning systems range from an abrupt separation in which the foal and mare are separated immediately from all contact (sight, sound, smell) to a more progressive separation. Com-plete, abrupt separation usually involves moving the mare to another turnout area, or moving the foal into confinement and separated completely from any type of mare contact. If using this method, it is best to not isolate the foal entirely. Foals weaned individually exhibit a higher level of proliferation of white blood cells than foals weaned in pairs. Foals weaned by complete, abrupt separation may have more weaning stress than foals weaned with progressive separation in which the foal and mare are allowed a period of time with visual, auditory (sound) and olfactory (smell) contact before complete removal. Instead of immediately removing the mare from all contact, a mare and foal are separated by being placed in enclosures with a common side. Once separated, the foal and mare are not allowed contact that facilitates nursing; however, fences or stall partitions allow for visual contact. The presence of the mare in an adjoining enclosure allows the foal to retain the security and comfort of its dam during the first several days after separation even though nursing is restricted. After being housed in an adjoining area for several days to a week, the mare and foal should be moved completely away from one another.

Alternative methods will allow for more contact with peers, or remain in a more stable social environment. One of the best ways of lessening weaning stress is to maintain familiar surroundings by leaving the foal in the same area it occupied previously and by weaning with other foals of like size and age. This can be accomplished by simply removing the dam of the oldest foals first, leaving the foal in its familiar environment with the other dams and foals. The presence of other tolerant adults also may lesson the stress of weaning. Foals housed with unrelated adults also show less stress (lower cortisol and vocalization) and fewer behavioral abnormalities (increased aggression) than foals weaned with only their peers. Presumably, this mimics a more natural weaning system than abrupt weaning into a young horse only group. For example, paired weaned foals may exhibit more inter-aggressive behaviors than foals weaned in their stable social groups in familiar environments. It is not advised to introduce weaning through short-term mare/foal separation, because it results in no improvement in behavior upon weaning, and seems to increase the mare’s maternal behavior upon return to the foal. In fact, it has been suggested to sensitize the stress response to separation.

Regardless of system, foals should be watched closely when weaned, especially the first 12 hours to 24 hours. Also, facility construction and design must emphasize safety. Any protrusions, such as feed troughs, can readily result in injury of nervous foals. Any opening larger than a foal’s hoof has the potential for trapping the leg of a foal.

Stereotypies

Stereotypies are patterns of behavior that occur repetitively with no apparent function, typically in response to stress. Development of abnormal behaviors also may occur during weaning. These may include oral stereotypies such as cribbing. The stress of weaning combined to a shift to a high grain diet fed at infrequent intervals can result in increased acidity of the stomach. Foals that demonstrate cribbing behavior have a higher degree of inflammation and ulceration of the stomach. It is therefore recommended to not only supply forage throughout the day for the weanling to allow continual eating patterns, but to try and divide the concentrate potion of the diet into more frequent feedings. In addition, foals weaned in groups in a pasture were found to develop less stereotypes over time than foals weaned in stalls or barns, whether singly or in pairs. Despite the method chosen for weaning, it is important that the foal is already accustomed to its diet prior to weaning.

Mare Care During Weaning

Most mares calm down more quickly than their foal, especially mares who have foaled in past years. The time required for her to resume normal behavior may vary from a few hours to several days.

If the mare still has significant milk production, the manager should decrease grain intake and increase exercise. A small amount may periodically be milked out by hand if the udder becomes very tight, but this practice is discouraged unless absolutely necessary. If the udder is still tight four days after weaning and the mare’s temperature rises significantly, or other indications warrant it, the milk should be checked for the presence of mastitis (infection) and appropriate therapy instituted. Veterinarian assistance is recommended.

Post-weaning Care

Management and Health Care

Hoof care should include periodic trimmings and inspection for cracks, bruises and abscesses. The frequency of trimming will be influenced by the conformation of the foal, the normal wear of hooves, exercise and housing. One advantage to pasturing weanlings is that continual access to exercise may benefit normal hoof growth and wear. Stalled weanlings prob-ably will need more intensive and frequent hoof care.

Handling practices will vary with the use of weanlings. Weanlings that are shown in halter classes or fitted for sales will receive daily handling and training. Brushing and other normal cleaning routines not only help the general health status of the weanling, they also serve to gentle and train the weanling to accept handlers. Those weanlings housed in pastures that do not receive the daily care of stalled wean-lings should be periodically handled, brushed and led. These handling sessions will better prepare weanlings for when they receive ground training and breaking to saddle in subsequent years.

Commonly recommended vaccinations include tetanus, sleeping sickness, rhinopneumonitis, influenza, rabies, West Nile and strangles. Deworming products are specific to types of worm infestation, and frequency of administration is influenced by product efficacy, reinfestation rates and environmental conditions. Vaccination and deworming schedules will be influenced by your locale and management practices, so consultation with a veterinarian is recommended.

Feeds and Feeding

Generally, 50% to 60% of mature weight and 80% to 90% of wither height is reached by 12 months of age. The exact body condition and rate of gain needed to promote sound growth of muscle and bone is debatable and perhaps somewhat flexible. Individual differences in genetic makeup create so much variation that general recommendations are limited in scope and accuracy.

Generally, weanlings should be fed individually at rates to maintain a moderate body condition. Weanlings expected to mature at 1,100 to 1,200 pounds should gain between 1.25 to 2.0 pounds a day. Most weanlings will consume between 1.5 and 2.0 pounds of grain per 100 pounds of body weight per day; and 0.5 to 1.0 pound of forage per 100 pounds of body weight per day to meet their needs for growth in moderate conditions.

Extremes in body condition should be avoided. Rations should be reduced when large amounts of body fat are deposited, and increased if the ribs or other bony structures become apparent. Also, weanlings fed to grow at consistent rates will have less structural problems, when compared to those restricted in growth for several months, then fed to gain rapidly.

There are numerous grain mixes available that have been formulated to contain the proper balance of protein, minerals and vitamins to energy for weanling horse needs. This balance ensures adequate amounts of these nutrients at different energy intakes and rate of growths. Most weanling rations will have between 1.2 and 1.3 Megacalories of digestible energy per pound. To ensure adequate protein and minerals, these rations (forages and grain combined) should contain 13% to 15% crude protein, 0.6% calcium and 0.45% phosphorous. The concentration of nutrients in the grain mix will depend on the type and level of hay or pasture forage. To ensure adequate nutrient intake with different forages, grain mixes formulated for weanlings typically will contain a minimum of 14% crude protein, 0.7% calcium and 0.5% phosphorus.

The most common problems with nutrition of growing horses are from over- or under-feeding, making sharp increases in rates of gain by sudden changes in amounts of feed or by feeding unbalanced rations. Unbalanced rations commonly occur when grains are added to commercially formulated mixes on-site, or feeding grains without vitamin or mineral supplementation.

Housing and Exercise

Many weanling horses are turned out in pastures with other similarly aged horses. There are several advantages to managing weanlings together in a pasture as compared to housing in stalls. Weanlings will interact with one another, and the behavior the weanling exhibits later in life may be more characteristic of expected behaviors in all horses as compared to weanlings housed separately. The need for forced exercise is lessened, and research suggests that weanlings managed extensively in pastures will have less frequency of bone growth problems. This is most likely due to a combination of factors related to free access to exercise and nutrients in the pasture forage. Continuous, free access to exercise may benefit bone strength and hoof formation. Also, horses may be managed for slower growth rates in pastures.

Those showing or marketing young horses require horses to be managed and housed individually. Stalled horses generally receive more individual care, regulated feed intake and hair can be kept in better condition. Exercise is important, as stalling without forced exercise can inhibit development of bone strength in weanlings. Single exercise bouts should be short in duration and apply enough stress to stimulate sound muscle and bone growth without over-exertion.

Successful forced exercise programs for stalled weanlings have incorporated a number of practices: timed turnouts with other growing horses, ponying, longeing and use of mechanical devices, such as horse walkers and treadmills. One practical management method has been to follow short-duration, controlled exercise bouts with longer-duration, free-access turnouts. Exercise programs must be individualized and adjusted with the development of each horse. Exercise level and intensity should begin conservatively and increased as positive responses are achieved. Evidence of mild soreness or joint swelling must be recognized before becoming severe and the subsequent level of exercise reduced until the horse responds more favorably.

Summary

- In most management systems, foals are weaned between four and six months of age.

- Weanlings require a more nutrient-dense diet and should be fed accordingly.

- Creep feeders must only allow access by the foal, be safe, sturdy and checked often.

- If possible, wean foals gradually or in groups with their peers in familiar environments.

- Ensure foals are eating their weaning ration prior to separation.

- Monitor health status, as the stress of weaning can result in an immunocompromised foal.

References

K. Malinowski, N.A. Haliquist, L. Helyar, A.R. Sherman, C.G. Scanes. Effect of different separation protocols between mares and foals on plasma cortisol and cell-mediated immune response. J Equine Vet Sci, 10 (5) (1990), pp. 363–368

HenryS. Zanella AJ, Sankey, C, Richard Yris, MA, Marko A and Hausberger M. Adults may be used to alleviate weaning stress in domestic foals (Equus caballus). Physiology and Behavior. 106(4): 428-438.

Waran, N.K, N. Clark, M. Farnworth. The effects of weaning on the domestic horse (Equus Caballus) Applied Animal Behavior Science. 110 (1-2): 42-57

Kris Hiney

Extension Equine Specialist