The Livestock Forage Program Disaster Assistance

Of the three primary livestock disaster assistance programs authorized in the 2014 Agricultural Improvement Act—the Livestock Forage Program (LFP); the Livestock Indemnity Program (LIP); and the Emergency Assistance for Livestock, Honeybees and Farm-raised Fish Program (ELAP)—the Livestock Forage Program has been the most utilized. From January 2011 to December 2018, LFP distributed $6.82 billion, and Oklahoma received 20 percent of those payments (FSA Data, Figure 2). LFP provides disaster assistance to eligible producers who experience specified periods of drought during a normal grazing season, resulting in grazing losses that require commercial livestock to be sold or otherwise disposed of (FSA, 2018). The program partially offsets the impact of drought-related damage to native or improved pastureland. Payment levels are determined based on the cost of feed or forage and drought category, rather than livestock market prices.

How are payments tied to drought?

Drought is categorized into four levels by the U.S. Drought Monitor1 : Moderate (D1), Severe (D2), Extreme (D3) and Exceptional (D4). U.S. Drought Monitor also tracks areas that are abnormally dry (D0). If a county is rated as having severe (D2), extreme (D3) or exceptional (D4) drought for eight consecutive weeks, then producers in that county may apply for an LFP payment. The drought rating is tied to the county level, not the farm level, so land that crosses county lines may not be eligible for the same level of payment on all acres.<br ?–> The degree and length of drought also factors into the payment levels. LFP payments are made based on a portion (60 percent) of either monthly feed cost for all livestock or the carrying capacity of the grazing land. The lowest of the two monthly livestock feeding cost proportions is used to determine the payment rates, which are published by FSA. For example, in 2018 the payment rate per head was $28.07 per head for adult beef cows (FSA, 2018). The payment rate per head is then multiplied by a factor determined by the degree and length of drought that is published once a year as shown in Figure 1. USDA-FSA refers to this factor as the “payment months,” and are determined as follows (FSA, 2018):

- The payment month will equal one when severe drought (D2) was experience for eight consecutive weeks in the county during the normal grazing season.

- The payment month will equal three when extreme drought (D3) was experienced at any time during the normal grazing season in the county.

- The payment month will equal four when extreme drought (D3) was experienced for at least four weeks or when exceptional drought (D4) was experienced at any time during the normal grazing season in the county.

- The payment month will equal five when four weeks of exception drought (D4) were experienced in the county, and they do not have to be consecutive weeks.

Payments will not exceed five payment months in any given grazing season for a particular piece of land.

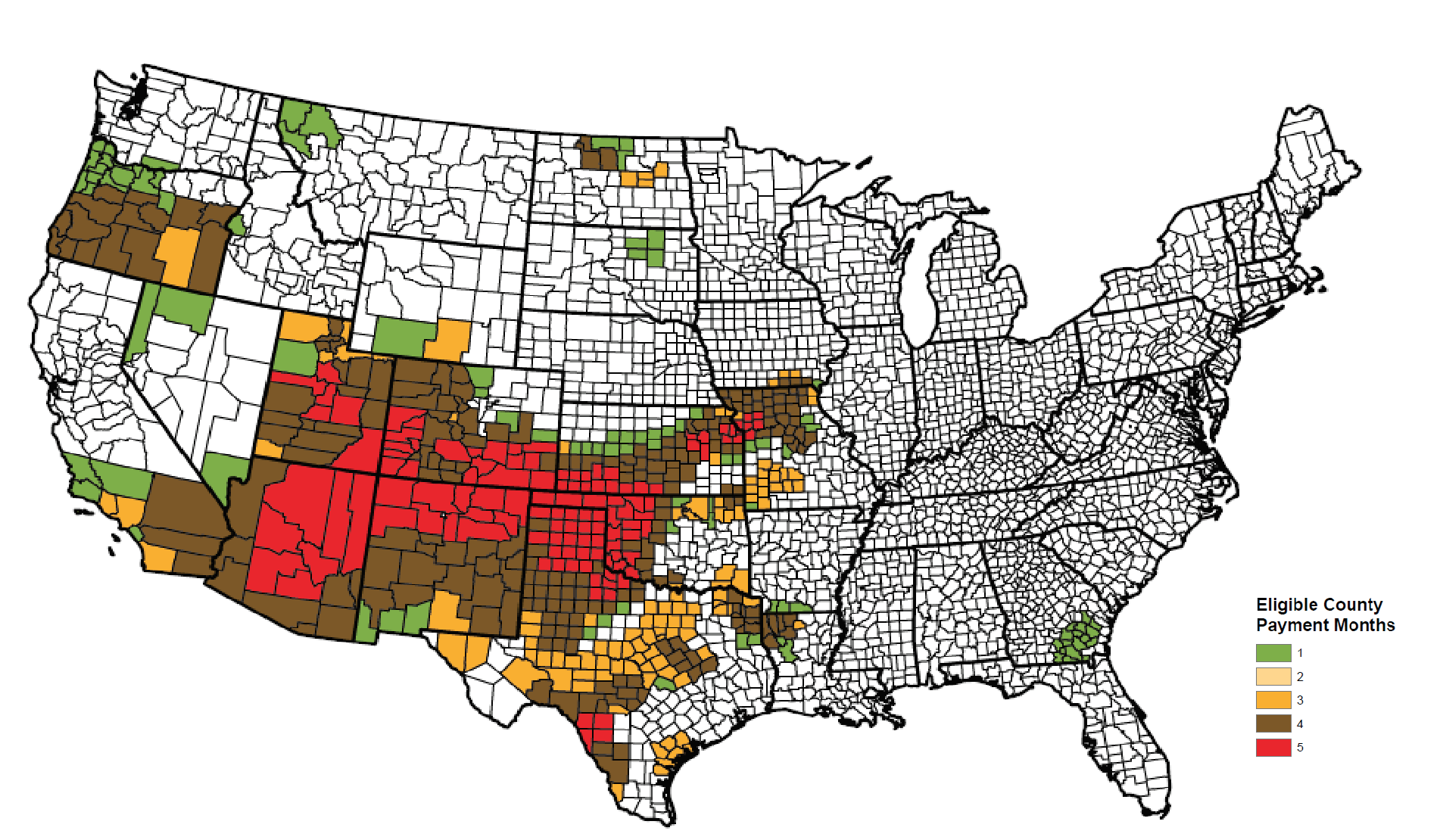

Figure 1. Eligible counties for Livestock Forage Disaster Program payments on native pasture in 2018.

Source: United States Department of Agriculture, Farm Service Agency. Published 10-18-18.

What are the eligibility requirements?

A key part of the program is that the livestock and the land must be in the applicant’s control, though this does include cash land rent situations. Land can include owned land, cash-rent pasture or rangeland managed by a federal agency2 for which the applicant has access during the normal grazing season. Livestock must be owned, purchased or under the applicant’s control within 60 days of the qualifying drought or fire event. Livestock must have been sold or disposed of due to the drought or fire in the production year. During the grazing season, the livestock must have been held on grazing land for commercial purposes, meaning some types of livestock are ineligible. This includes livestock that were used for pleasure or hunting including wild deer or elk; kept as pets; or roping or show animals. Commercial livestock that would not be grazing under normal conditions, such as livestock in a feedlot, also are not eligible. However, the types of commercial livestock eligible for LFP is quite diverse, including: alpacas, beef cattle, buffalo/bison, beefalo, dairy cattle, commercially raised deer and elk, emus, goats, horses, llamas, reindeer and sheep.

Use of LFP in Oklahoma

Historically, Oklahoma producers have taken advantage of the LFP drought relief funds. According to Farm Service Agency data, in 2018 almost 40 percent of LFP payments went to Oklahoma producers. In that year, more than 10,000 Oklahoma farmers applied for LFP and received a total of $65 million in payments. The greater the drought, the more extensively the program has been used. For example, in 2012 — a year of significant drought in Oklahoma — 34,000 Oklahoma producers met the LFP eligibility requirements and received a total of almost $397 million. In fact, across the last eight years (2011 to 2018), Oklahoma producers have received almost $1.4 billion in relief funds from this program (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Total Livestock Forage Disaster Program payments by state from 2011 to 2018.

Source: United States Department of Agriculture, Farm Service Agency

Oklahoma example 1:

How might a livestock producer in Oklahoma use the LFP program? An example of a cow-calf producer in Washita County that experienced drought in the summer of 2018 on his native pasture can be examined. Rather than feed hay, he sold 20 cow-calf pairs in August due to those drought conditions. Is he eligible for an LFP payment? He would first talk to his Washita County FSA agent to make sure he met all of the eligibility requirements. He owned the land and owned the cows in the 60 days leading up to the drought. He has a sales receipt for the pairs, which were commercial purpose livestock. He filed an acreage report when he realized that he might be eligible for an LFP payment, if he didn’t already have one on file. Assuming he met all of the requirements, he would receive a payment of $2,245.60.

LFP payment = head × payment rate per head × payment months

Washita County cow-calf producer example payment = 20 × 28.07 × 4 = $2,245.60

What can I do to prepare for drought?

Weather is a risk that Oklahoma farmers and ranchers are familiar with and drought, in particular, threatens pasture quality in the state. The wind can quickly dry out the little bit of available moisture in some counties. The LFP is one of several disaster payment programs that ranchers can take advantage of when drought occurs. If the LFP might be a program you can benefit from, there are some things you can do now. To receive a payment, you will need to have an acreage report on file with FSA for all grazing land. For example, to claim a payment on a native pasture for the 2018 grazing season as shown in Figure 1, you will need to have had a pasture acreage report filed between November 15, 2017 and November 14, 2018. Applications for payment can be submitted until 30 days after the calendar year when the loss was incurred, but only if that acreage report is on file. Also, you will need to certify that you have suffered a grazing loss due to drought or fire on the application and provide documentation that the livestock were physically located in a county eligible for an LFP payment.

For more information

The LFP is administered by the Farm Service Agency (www.farmers.gov). This fact sheet is designed to give you some general information before meeting with the local FSA agent. If you have any questions on the process, eligibility and limitations, contact the local FSA office to have a discussion specific to your business.

References

Farm Service Agency (FSA). 2018. Livestock Forage Disaster Program Factsheet. United

States Department of Agriculture. Available online at: https://www.fsa.usda.gov/programs-and-services/disaster-assistance-program/livestock-forage/index

MacLachlan, M., S. Ramos, A. Hungerford, S. Edwards. 2018. Federal Natural Disaster

Assistance Programs for Livestock Producers, 2008-16. United States Department of

Agriculture, Economic Research Service. EIB-187. Available online at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=86989

- https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/CurrentMap.aspx

- Additional guidance for LFP eligibility for producers who are prohibited from grazing on federally managed range land due to drought or fire can be found online through www.farmers.gov

Amy D. Hagerman

Assistant Professor, Ag and Food Policy