Seedling and Root Diseases of Soybean

Introduction

Seedling and root disease of soybean are often referred to as soilborne disease because the pathogens that cause them survive in soil. Soilborne diseases that affect seedling and roots in Oklahoma are caused by fungi and nematodes. Where levels of soilborne diseases are high and conditions favor disease development, yield losses can occur. Correct identification and early detection are critical in the proper management of soybean diseases. This fact sheet is intended to aid Oklahoma soybean producers in recognizing common soybean diseases that attack seedlings and roots.

Seedling Diseases

Seedling diseases, also known as damping off or seedling blight, are caused by a group of fungi, acting independently or together, that cause seed, root, and lower stem rot on young plants. These diseases are classified as being either pre-emergence or post-emergence. Seedlings that become diseased prior to emerging through the soil surface have pre-emergence seedling disease. Seedlings that become infected after emerging through the soil surface have post-emergence seedling disease. Fungi associated with seedling diseases include Fusarium, Phomopsis, Phytophthora, Pythium, and Rhizoctonia. These fungi are common wherever soybeans are grown and are either seedborne or soilborne pathogens.

Seedling diseases are usually associated with factors that cause stress to young plants. Factors such as cool and wet soil, poor seed quality, improper planting depth and herbicide injury can all play a role in predisposing seedlings to seedling disease.

Dark brown or reddish colored lesions on the lower stem or main root are symptoms of seedling disease (Figure 1). Alternatively, infected stems develop a watery lesion at the soil line where the seedling breaks just prior to its death. Fields infected with significant amounts of seedling disease have thin stands and uneven plant growth. Infection may occur before or during germination, or after emergence before the first set of trifoliate leaves develop.

Seedling diseases can be reduced by delaying planting until soil temperatures increase above 68 F and by planting high quality seed. A fungicide seed treatment can reduce seedling diseases and improve stand, especially in early planted soybeans. Seed treatments are relatively inexpensive and in most cases ensure a good stand. However, seed treatments will not make up for poor quality seed with less than 85 percent germination. Consult the most recent Soybean Production Guide (Extension Circular E-854) or the OSU Extension Agents Handbook of Insect, Plant Disease, and Weed Control (Extension Circular E-832), available at your local county Extension office for the latest information on fungicide seed treatments registered for use on soybeans.

Figure 1. Seedling disease.

Root and Lower Stem Diseases

Phytophthora Root Rot (Phytophthora megasperma var. sojae)

Phytophthora root rot is a soilborne disease that primarily occurs on soybeans that are growing in poorly drained soils with a high clay content. Symptoms include wilting of the plant, yellowing of leaves, and the development of an elongated, water-soaked lesion on the lower stem and roots (Figure 2). Leaves on older plants first turn yellow between the veins prior to wilting and plant death. The dead leaves remain attached to the plant.

Control of Phytophthora root rot is obtained by planting resistant varieties. There are many races of the pathogen, but varieties with resistance to multiple races are available. Low, poorly drained fields with clay-type soils should be avoided when planting susceptible varieties.

Figure 2. Phytophthora root rot.

Southern Stem Blight (Sclerotium rolfsii)

Southern stem blight occurs on a wide range of host plants, including soybeans. Damage to soybean from southern stem blight is generally restricted to scattered, localized areas of dead plants that usually appear during the mid to latter part of the growing season.

Symptoms of southern stem blight are wilting and dying of plants in small patches. Decayed areas of the lower stem near the soil line are tan to dark brown in color. The key sign of southern stem blight is the white, moldy growth on the main stem at the soil surface (Figure 3). Small, circular, tan to brown colored reproductive structures called sclerotia, are often formed in association with the white mold. Sclerotia, which resemble mustard seeds, fall to the soil where they survive for more than a year. Control of southern stem blight is best obtained through crop rotation with grass crops such as corn and grain sorghum, or with cotton. Avoid planting soybeans following crops such as peanuts, alfalfa, and melons which are very susceptible to southern stem blight.

Figure 3. Southern stem blight.

Charcoal Rot (Macrophomina phaseolina)

Charcoal rot is a common soiilborne fungal disease of soybeans in Oklahoma. Yield losses due to charcoal rot are difficult to measure because the disease is closely associated with drought stress and nutrient deficiencies. High plant populations, soil compaction, and nematode infestations also increase the incidence of charcoal rot.

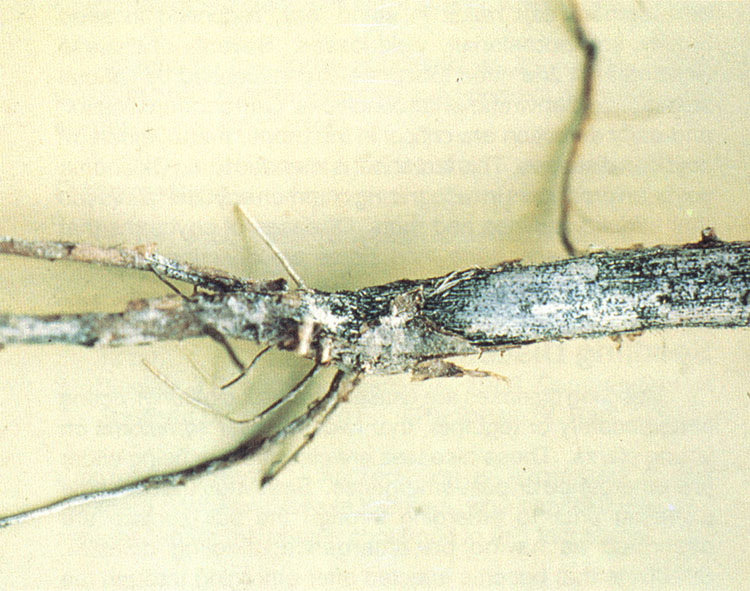

Symptoms appear in hot, dry weather usually after the plants have initiated flowering and have begun setting pods. Leaves of infected plants turn yellow, and entire plants wilt and die with the leaves remaining attached. Wilted plants often occur in circular patches. The most reliable diagnostic symptom is the development of tiny black specks (sclerotia) just beneath the surface of the tap root and lower stem (Figure 4). Sclerotia are best observed with the aid of a hand lens. The small sclerotia impart a charcoal color in diseased stems and roots, hence the name charcoal rot.

Since this disease is associated with stressed plants, incidence of charcoal rot can be reduced through proper fertilization, weed control, and irrigation. Crop rotation with poor hosts of the fungus, such as cotton or small grains, for one to two years, can help in minimizing yield loss due to charcoal rot. There are no known resistant varieties; however, varieties that do not bloom and set pods during the normally dry months of July and August are more likely to escape infection by charcoal rot. There are no known chemical controls.

Figure 4. Charcoal rot.

Nematodes

There are several different species of nematodes that feed on soybeans, but only two are known to be important on Oklahoma soybeans. Root-knot nematode and soybean cyst nematode have been detected in Oklahoma soybean fields. Of these, the soybean cyst nematode is more widespread and damaging to soybean yields.

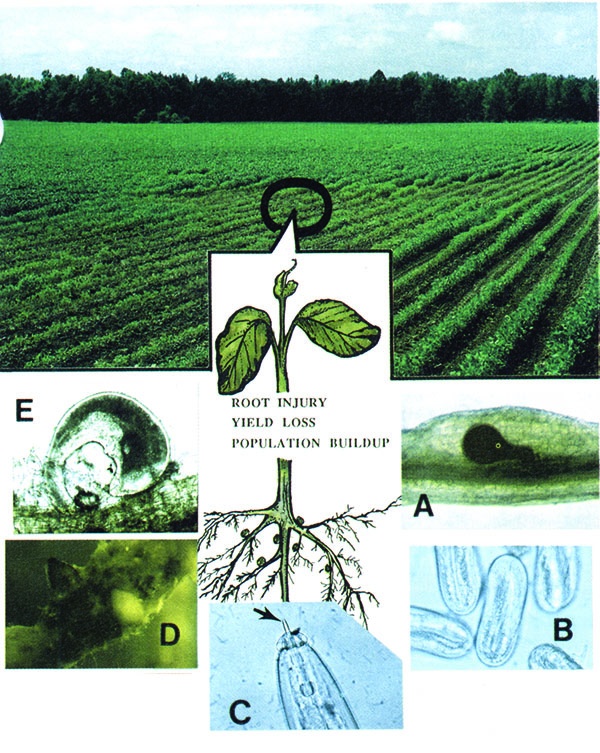

Above ground symptoms of nematode feeding on roots are not specific. Sometimes nematode-infested plants are yellow and stunted (Figure 5). Stunted plants are often clumped within a row, which causes an uneven or wavy appearance to the rows. However, the amount of yellowing and stunting can vary dramatically between and within infected fields. Sometimes, there are no visual symptoms at all, or symptoms of other plant stresses such as drought or nutrient deficiency may be very pronounced.

The presence of root-knot or soybean cyst nematodes can frequently be diagnosed in the field. Root-knot nematode causes the roots to produce characteristic swellings or galls (Figure 6) which are easily distinguishable from nitrogen-fixing nodules (Figure 7).

Female soybean cyst nematode can often be observed in the field as white to yellow cysts attached to the roots (Figure 8). Although visible to the naked eye, the female cysts are very small and can easily be missed. The most reliable method of detection is to submit a soil and root sample to the OSU Plant Disease and Insect Diagnostic Laboratory. (Contact your local OSU County Extension Agriculture Educator for information on sampling for nematodes.)

Control of both root-knot and soybean cyst nematodes is most effectively obtained through a nematode management program. The goal of the management program is to reduce nematode populations below damaging levels and to prevent the development of races or strains capable of damaging resistant varieties. The use of crop rotation combined with soybean varieties resistant to soybean cyst and/or root-knot nematodes generally provides control of these pests. The effectiveness of resistant varieties decreases over time if they are continually grown in nematode-infested fields.

An alternation of nematode resistant and susceptible varieties helps preserve resistance traits. A minimum four-year rotation is recommended.

Year 1: Nonhost crop.

Year 2: Soybean cyst nematode resistant variety.

Year 3: Nonhost crop.

Year 4: Soybean cyst nematode susceptible variety.

Figure 5. Plant pathogenic nematodes of soybeans. Above ground symptoms reflect injury caused by root-feeding nematodes. A. root-knot nematode: female (stained red) feeding in root tissue; B. nematode eggs; C. head region of nematode with stylet protruding (arrow); D. soybean cyst nematode (yellow and brown cyst stages adhering to root segment); E. Reniform nematode: (female with head embedded in root).

Figure 6. Galls on roots caused by the root-knot nematode.

Figure 7. Nitrogen fixing-modules that develop on healthy plants.

Figure 8. Soybean cyst nematodes produce small white

to pale yellow cysts that contain eggs.

Nonhost Crops for Soybean Cyst Nematode

- alfalfa

- canola

- corn

- cotton

- forage grasses

- rye

- melons

- oats

- peanuts

- red clover

- rice

- sorghum

- wheat

Nonhost Crops for Root-Knot Nematode

- wheat

- corn

- oats

- rye

For fields infested with root-knot nematode, a similar rotation should be followed with root-knot resistant or susceptible varieties inserted in the rotation in place of the soybean cyst nematode varieties.

Disease Management Principles

A basic strategy for control of soybean diseases is prevention. The following suggestions are offered in an attempt to provide soybean producers some basic guidelines that will aid in the prevention of soybean diseases.

- Plant high quality, preferably certified seed.

- Apply fungicide seed treatment.

- Use proper seedbed preparation, planting depth, and seeding rates.

- Practice crop rotation with non-legume crops.

- Plant disease and nematode resistant varieties.

- Practice good management of fertility, weeds, and insects.

Integrating the above principles, as they apply, into a soybean production program will help prevent diseases from reducing yield.

References

Colyer, P.D. (ed) 1989. Soybean Disease Atlas, 2nd Ed. Associated Printing Professionals, Inc., 43 pp.

Pratt, P., P. Bolin, and C. Godsey (eds). 2011. Soybean Production Guide. OCES Circular E-967, 129 pp.

Hartman, G.L., J.B. Sinclair, and J.C. Rupe (eds). 1999. Compendium of Soybean Diseases, 4th Ed. APS Press, St. Paul, 100 pp.

John Damicone

Extension Plant Pathology Specialist