Pine Wilt Disease

Pine wilt is a devastating tree disease affecting many non-native pines in Oklahoma, particularly in residential areas through the I-35 corridor and eastward. The disease can kill trees in as little as three weeks. In the Midwest, the most commonly killed trees are Scotch (Scots) (Pinus sylvestris) and Austrian (P. nigra) pines, both of which are highly susceptible to pine wilt. Jack (P. banksiana) and mugo (P. mugo) pines are moderately susceptible. Native pines including ponderosa (P. ponderosa) and white (P. strobus) pines are seldom affected by pine wilt, but they may be affected if the trees are suffering damage from other pest or disease problems or environmental stress. The disease does not affect other evergreens such as those listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Alternative evergreens (partial list) for Oklahoma. The plants below, all available as trees or in tree-like forms, will provide year-round beauty, and are not susceptible to pine wilt nematode.*

| Common name | Latin name | |

|---|---|---|

| California incense cedar | Calocedrus decurrens | |

| Atlas cedar | Cedrus atlantica | |

| Alaska cypress | Chamaecyparis nootkatensis | |

| China fir | Cunninghamia lanceolata | |

| Cryptomeria | Cryptomeria japonica | |

| Arizona cypress | Hesperocyparis arizonica | |

| Sky Pencil holly | Ilex crenata ' Sky Pencil' | |

| American holly | Ilex opaca | |

| Weeping yaupon holly | Ilex vomitoria ' Pendula' | |

| Upright yaupon holly | Ilex vomitoria ' Will Fleming' | |

| Chinese juniper | Juniperus chinensis | |

| Rocky Mountain Juniper | Juniperus scopulorum | |

| Taylor juniper | Juniperus virginiana ' Taylor' | |

| Southern magnolia | Magnolia grandiflora | |

| Southern waxmyrtle | Morella cerifera | |

| Colorado spruce | Picea pungens | |

| Cherry laurel | Prunus laurocerasus | |

| Live oak | Quercus virginiana | |

| Arborvitae | Thuja spp. |

*Not all trees or tree-like plants listed above are necessarily top plant materials for Oklahoma. Geographically speaking, some are not appropriate for all regions of the state. However, all are viable substitutes if consumers choose to grow species that are evergreen, but are not pines. Consumers should seek advice from a reputable grower or retailer regarding pines known to be relatively risk-free from this disease. For additional evergreen considerations, see HLA-6463 Selecting Evergreen Trees.

Symptoms

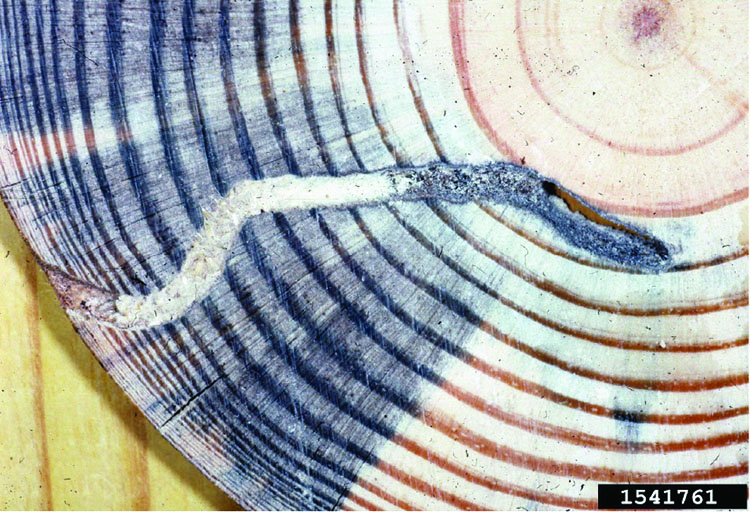

In most cases, trees that develop pine wilt are more than 10 years old. Typically, symptoms appear in July and may develop through December. The needles on a few branches will initially fade to green-gray and wilt (Figure 1). Needles remain attached and resin flow is reduced, resulting in the wilt symptom. The disease spreads rapidly inside the tree and within a few weeks, the entire tree may show symptoms of wilt and browning (Figure 2). In general, infected trees die quickly, often in a single growing season. It is not uncommon for infected trees to occur in close proximity to healthy trees (Figure 3). Dying or dead trees typically exhibit blue stain symptoms in the wood when cut (Figure 4).

Figure 1. Early symptoms of pine wilt are visible as wilted, gray-green or brown needles which remain attached to the tree.

Figure 2. This entire pine tree has recently wilted and the needles are gray-brown due to pine wilt disease.

Figure 3. Trees with pine wilt may be found adjacent to unaffected pine trees.

Figure 4. This pine stump shows blue staining that is common in dead and dying pine trees.

Pinewood nematodes

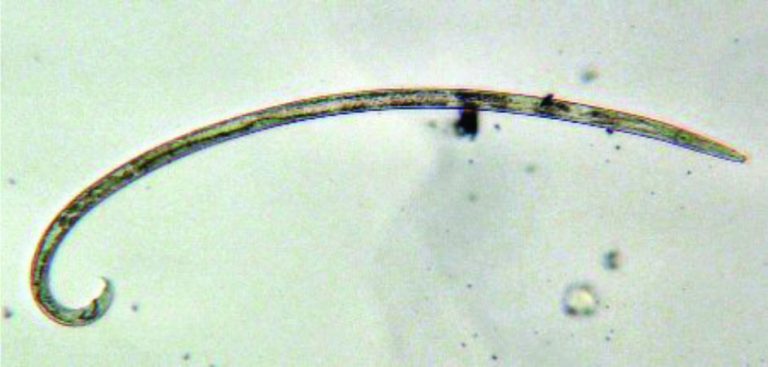

Pine wilt disease is caused by a microscopic (1 mm) roundworm called the pinewood or pine wilt nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (Nickle) (Figure 5). Pinewood nematodes are foliar nematodes and are found in the aboveground portions of trees. The life cycle of the pinewood nematode is very short, developing from egg to adult in three to five days. In the early stages of pine wilt, pinewood nematodes feed on plant cells surrounding resin canals or water-conducting (xylem) cells in pine trees. As nematode populations increase rapidly, they move throughout the tree and interfere with the flow of water and nutrients. Efforts by the tree to stop nematode movement further exacerbates the disease, ultimately resulting in death of the tree. When pine trees are near death, they often are invaded by blue-stain fungi (Ceratocystis spp.). Pinewood nematodes can then survive by feeding on blue-stain fungi after the trees have died.

Figure 5. A microscopic pinewood nematode has been extracted from diseased pine wood. The pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus, has distinct characteristics that allow it to be distinguished from free-living nematodes.

Pine Sawyer Beetles and Spread of Pine Wilt

Pinewood nematodes have a unique relationship with longhorned beetles known as pine sawyer beetles (Figure 6). At least two species of pine sawyers, Monochamus carolinensis (Oliver) and M. titillator (Fab.), occur in Oklahoma. Both species occur widely in the southern and eastern U.S. and west into eastern Oklahoma and Texas. Adult pine sawyer beetles measure ¾ inch to 1 ¼ inches in length and have a gray and green body (Figure 6). Pine sawyers have long antennae; the antennae of males may be two to three times the length of the body. Larvae are legless white grubs, have a brown head, and are about 2 inches long when fully grown (Figure 7). While feeding, the larvae make an audible noise that sounds like sawing; hence, the insect’s common name.

The life cycle of pine sawyer beetles is usually completed in roughly 50 days to 60 days. There is an average of 2 ½ generations per year in Missouri (details for Oklahoma are lacking). The female beetle chews a small hole in the bark of recently dead, dying or declining pine trees and lays her eggs. Young larvae feed on the inner bark, cambium and outer sapwood, forming shallow excavations (surface galleries). Older larvae bore into the heartwood and then tunnel back toward the surface, forming characteristic U-shaped tunnels (Figure 8). At the last stage of larval development, they form a pupal cell at the outer end of the tunnel near the surface of the wood. After pupation, the adult emerges by chewing a hole through the remaining wood and bark.

Pinewood nematodes are microscopic and cannot move from tree to tree without assistance from pine sawyer beetles. These nematodes have developed an intimate relationship with these beetles to facilitate transmission to new trees. As adult pine sawyer beetles emerge from wood colonized by pinewood nematodes, large numbers of nematodes have al-ready moved into the beetles’ respiratory openings (spiracles) and are thus carried in the tracheal system. Beetles become vectors for the nematodes as they visit healthy trees to feed on bark, thereby introducing nematodes into the tree through feeding wounds.

Pine sawyer beetles are most active from May through late September with disease symptoms usually appearing shortly thereafter from July through December. Newly emerged adults may visit healthy pines and feed on the bark and/or visit stressed or dying trees while feeding, mating or laying eggs. It should be noted that pine sawyer beetles rarely attack healthy, vigorously growing trees. Therefore, it is important to maintain the health of pine trees to reduce the spread of pinewood nematodes.

Figure 6. Southern pine sawyer, Monochamus titillator (male). Photo by Lacy L. Hyche, www.bugwood.org.

Figure 7. Larvae of southern pine sawyer. Photo by Lacy L. Hyche, www.bugwood.org.

Figure 8. Gallery of southern pine sawyer larva. Note blue stain fungi in xylem vessels. Photo by Lacy L. Hyche, www.bugwood.org.

Inspection and Control of Pine Wilt

Pine wilt disease differs from other pine tree diseases due to rapid decline of the tree (within a season). The disease is more common on exotic pine species, although native pines under stress are susceptible. Differences between pine wilt and other pine tree problems are noted in Table 2.

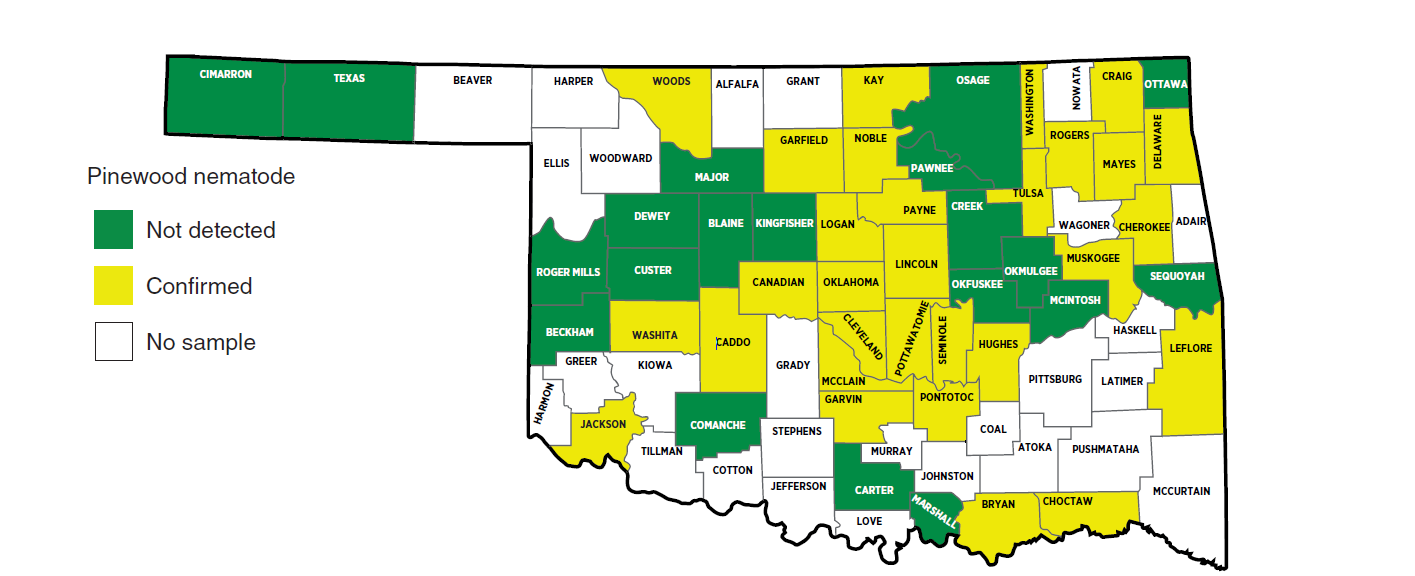

A map of the current known distribution of pine wilt disease in Oklahoma is shown in Figure 9. To positively confirm a case of pine wilt in a new area, a sample from the tree should be collected. Please follow the sampling recommendations in EPP-7675, Sampling for Pinewood Nematodes and submit samples through your local county OSU Extension office.

It is possible to treat healthy trees with an insecticide to kill beetles and prevent pine wilt infection. Preventative injections of abamectin can be made every year to two years to reduce the likelihood of pine wilt establishment. Injections can only be made by a tree care specialist, so a certified arborist should be consulted. Pine sawyers do not enter diapause during the winter, so some larvae feed, pupate and emerge during warm periods all year. Therefore, prevention of the disease using this method is not always successful. Once a tree is infected with pinewood nematodes, pesticides are no longer effective.

There is no cure for pine wilt once a tree is infected and dead trees left in the landscape are sources of both nematodes and pine sawyer beetles. Diseased trees should be destroyed by burning, chipping or burying. The stump should be removed or ground down and buried under 6 inches of soil.

Figure 9. Pinewood nematodes have been confirmed by sampling in the Oklahoma counties marked in yellow. At least one sample has been examined from the counties marked in green, but pinewood nematodes were not recovered. Counties marked in white have not submitted samples for testing. Based on data as of 2/19/2021.

Table 2. Comparison of pine wilt to other pine tree problems.

| Observation | Possible Pine Wilt | Other causes suspected | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pine hosts | Mainly non-native pines | All pine species | |

| Age of tree | Usually, older than 10 years | Any age | |

| Symptoms | Rapid discoloration and wilt | Stunting, spots, needle drop | |

| Time symptoms appear | Late summer to winter | Any season | |

| Progression of symptoms | Trees killed quickly, one to three months | May be rapid, but usually months or years | |

| Resin flow | Lacking | Present |

Replacing Trees in Areas with Pine Wilt Disease

Pine wilt is primarily a problem with pine trees not native to the U.S. and Oklahoma. In areas where pine wilt disease is common, more preference should be given to native pine selections. Native pines including, but not limited to, loblolly (P. taeda), shortleaf (P. echinata), white (P. strobus) and limber (P. flexilis), are suitable for planting in these areas. Consumers may want to consider the evergreens listed in Table 1 to supplement future plantings. Those listed are a few examples of alternative evergreens not susceptible to pine wilt. Each suggested plant also has related cultivars or species that can provide different heights, widths, foliage color or other characteristics. Consumers should consult with a local nursery or garden center professional for plants ideal for their geographic location. In most of western Oklahoma, pine wilt disease does not occur or is extremely uncommon. In these areas of the state, consumers have the freedom to plant non-native pine species. However, consumers should not plant more than 15% of their landscape with a single tree species.

In most of western Oklahoma, pine wilt disease does not occur or is extremely uncommon. In these areas of the state, consumers have the freedom to plant non-native pine species. However, consumers should not plant more than 15 percent of their landscape with a single tree species.

Pine Wilt Summary

- Consult your local county Extension educator if you suspect pine wilt symptoms. A laboratory analysis is necessary to confirm this disease.

- If pine wilt is confirmed, remove the tree as soon as possible. Destroy the tree by burning, burying or chipping. Stumps should be removed or ground and buried at least 6 inches deep

- For future evergreen plantings, consider pines native to the United States and fewer exotic pines.

- Consult with a nursery or garden center professional or see Table 1 of this publication for appropriate evergreen substitutes for your geographic area of Oklahoma.

Jennifer Olson

Extension Specialist for Plant Disease Diagnosis

Eric Rebek

Extension Specialist for Horticulture and Turfgrass Entomology

Mike Schnelle

Extension Specialist for Ornamental Floriculture