Ornamental and Garden Plants: Controlling Deer Damage

- Jump To:

- Commonly Used Control Methods

- Physical Exclusion

- Scare Tactics

- Population Reduction

- Repellents

- Using Deer Feeding Behavior

- Garden Plants—Severely Damaged

- Garden Plants—Frequently Damaged

- Garden Plants—Occasionally Damaged

- Garden Plants—Rarely Damaged

- Herbaceous Plants—Annual Flowers

- Herbaceous Plants—Annual Flowers

- Herbaceous Plants—Perennial Flowers

- Herbaceous Plants—Perennial Flowers

- Woody Plants—Frequently Damaged

- Woody Plants—Occasionally Damaged

- Woody Plants—Seldom Damaged

- Woody Plants—Rarely Damaged

- Acknowledgements

Oklahoma’s white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) (Figure 1) population has increased from 40,000 to around 500,000 since the 1960s. At the same time, urban development continues to move into deer habitat. Increasingly, homeowners at the rural/urban interface must deal with deer damage to ornamental and garden plants. As deer begin moving into an area, homeowners initially enjoy seeing deer and may actually encourage them to come into their yard by feeding them. Homeowner attitudes often begin to change after deer numbers increase to the extent that landscape plants show heavy browsing and gardens become difficult to grow because of continued depredation.

Deer have a varied diet that includes many broadleaf herbaceous and woody plants.

Deer are not considered grazers (i.e. as are cattle) but rather are considered browsing

animals. They prefer to consume forbs (broadleaf herbaceous plants), shrubs, young

trees, and vines. Deer will consume some species of grass, although damage is usually

minimal. While deer normally feed at night, as they become habituated to people,

they frequently are active during the daylight hours. Deer have no upper incisors;

they feed by tearing vegetation with their lower incisors and upper palate. Thus,

deer damage is easily identified by the jagged remains of browsed plant material.

Annuals are often pulled out of the ground completely. Woody plants are repeatedly

browsed and often exhibit a hedged appearance (Figures 2 and 3). In addition to browsing,

damage may occur in the fall when bucks begin rubbing antlers on small trees (Figure

4) or other young landscape plants.

Figure 1. White-tailed deer have become so abundant across Oklahoma that they are causing damage to property.

Figure 2. This elm shows classic browsing damage caused by white-tailed deer. Notice the hedged

shape from years of browsing. Although this tree species readily resprouts each year

following browse damage, deer are keeping the tree from reaching a tall stature.

Figure 3. An example of a browse line caused by deer. Woody plant species vary in how resilient

they are to this heavy browsing. But regardless of potential plant mortality, browse

damage can be aesthetically displeasing to homeowners.

Figure 4. Male white-tailed deer frequently rub trees both before and during the rutting period.

They normally choose small saplings that have a thin bark layer. This is problematic

for ornamentals in lawns and also for Christmas tree production.

Commonly Used Control Methods

The problem of damage control is not an easy one to solve. Rural subdivisions normally ban hunting or place restrictions on firearm use to protect deer or for safety reasons. Trapping and moving excess deer is often suggested by homeowners as a humane alternative to hunting. However, the cost to move enough deer to lower damage to tolerable levels is prohibitive. Also, most areas of Oklahoma are well populated with deer and any deer moved to another area will only shorten food supplies for both resident and transplanted animals. The excess animals will then face starvation or decreased reproductive success because of chronic malnutrition. Thus, trapping and relocating problem deer is a poor solution.

The first step in managing deer damage in the landscape is to make the landscape less attractive to deer. This is accomplished by limiting the amount of excess food in the landscape through removing all unharvested fruits and vegetables. Do not provide winter feed or salt for deer as an alternative to your landscape plants; the deer will feed on both the deer feed and your plants. When deer damage becomes a problem in the landscape, control methods include:

- exclusion—by electric fence or eight-foot high, deer-proof fence,

- scare or frightening tactics—with dogs, gas exploders, fireworks or motion-activated sprinklers,

- population reduction through hunting,

- repellents—area repellents repel by smell and contact repellents repel by taste, and

- alternative plantings/habitat modification.

Physical Exclusion

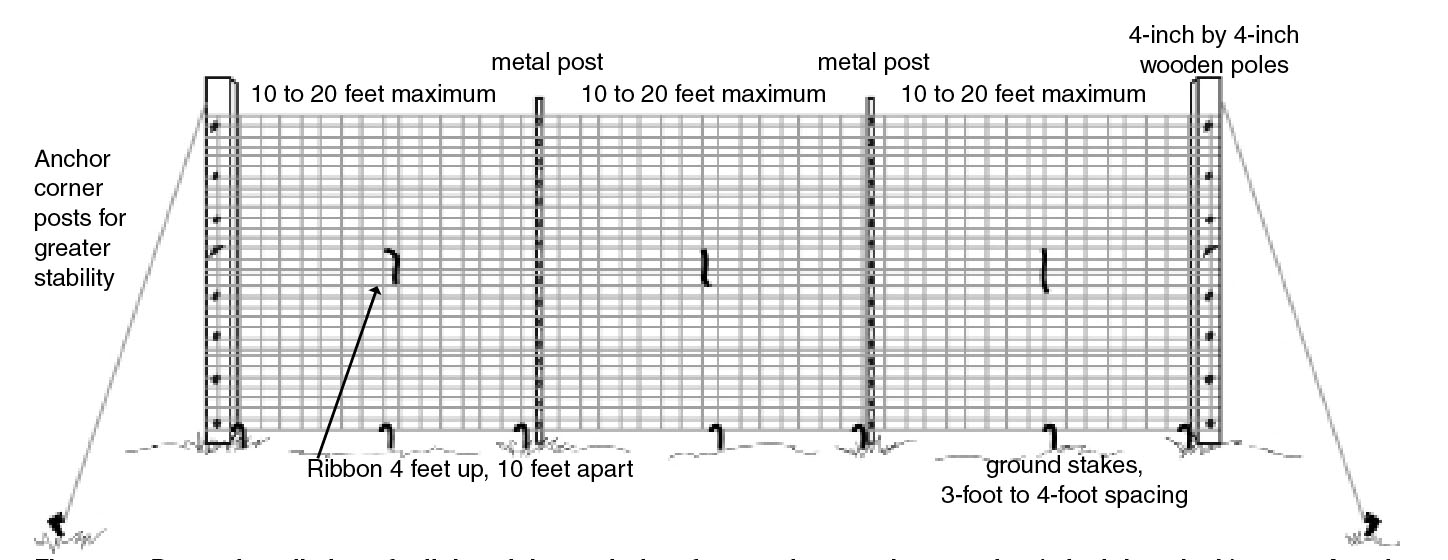

The most effective deer damage control method is the use of exclusion fences. Deer can easily jump over many decorative fences. To keep deer out of a landscape or garden, either an electric fence or eight-foot deer fence (Figure 5) is necessary. A deer-proof fence does not fit well with most landscaping plans and can be expensive if large areas are to be protected. One way to make fences less noticeable is to place them at the forest edge where they blend in with the surrounding shrubs and brush. Many deer fences are constructed in such a way as to become nearly invisible from a distance and new fencing materials are even less obtrusive. For small gardens, a deer-proof fence can be cost effective. Many commercial deer fencing materials are available. These are made of durable light weight polyethylene resistant to UV degradation. Deer fences can also be easily constructed using standard hog wire fence and 12-foot posts.

Figure 5. Proper installation of a lightweight mesh deer fence using metal or wooden (4-inch by 4-inch) posts. Attach strips of brightly colored ribbon to the fence at 10-foot intervals, four feet from the ground to make the fence more visible to deer.

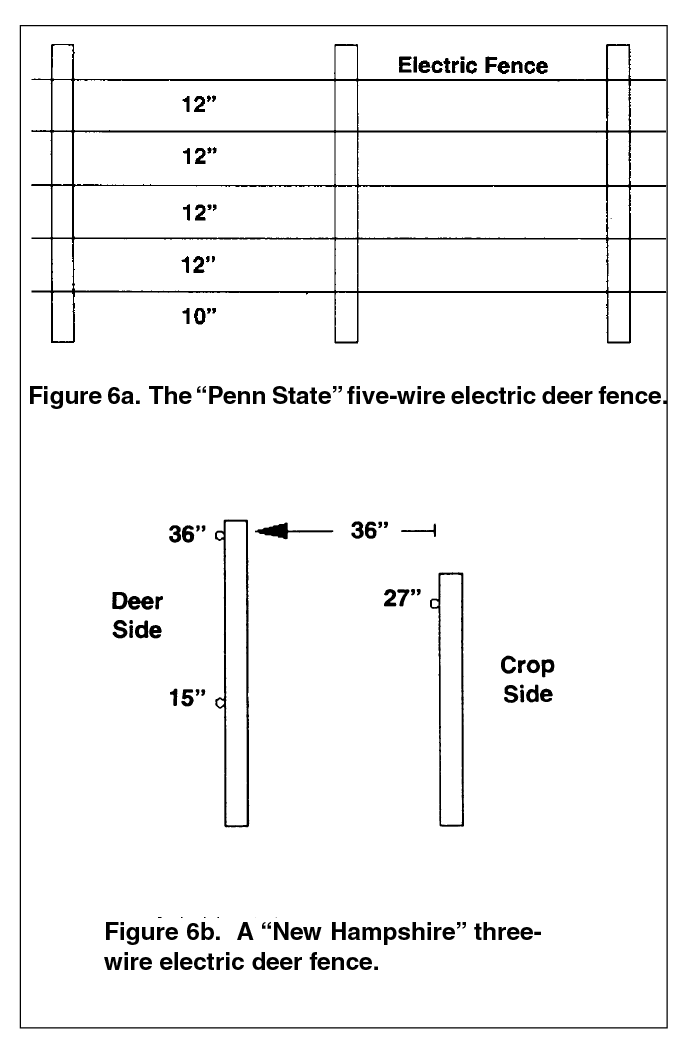

Electric fences (Figures 6a and 6b) are less expensive and can be just as effective; however, they do require greater maintenance. For best results, electrify the fence immediately after installation and keep electrified at all times. If an electric fence is not electrified for several days, deer may learn to go through it. Researchers have had some success with a three-wire electric fence (“New Hampshire” spacing) when baited aluminum foil strips are attached at 5-foot to 10-foot intervals. The ends of the strips are smeared with peanut butter for “bait.” Deer may learn to jump electric fences if incorrectly installed or maintenance is lacking. For very small areas (e.g. 8-foot x 8-foot) shorter fences of around 4 feet may be sufficient to protect garden plots. Deer can easily jump such short barriers, however they are normally hesitant to jump into small plots as it is more difficult to get out due to limited space within the plot. However, for most gardens this will not be a viable option.

Young trees are particularly sensitive to deer damage and are often killed through browsing. Individual trees can be easily protected from browsing damage using strong 8-foot tall wire cylinders (Figure 7). Hog wire fencing is recommended as chicken wire is not strong enough for deer protection. Stabilize the wire cylinder using t-posts and remove the fencing once trees have branched out of reach of deer. This can also be used to protect trees from deer rubbing their antlers.

Figure 7. Wire cages can be used to protect individual trees from deer damage. Support cages

securely using metal posts.

Scare Tactics

A number of scare tactics are used to frighten deer away from the landscape. Dogs are very effective at repelling deer. Products such as invisible fences allow the dog to patrol an area and see and harass deer that might be moving through. These devices in combination with dogs can greatly reduce deer damage assuming the dog spends most time outdoors and will actually harass the deer. Likewise, devices that produce loud noises or even flashing lights are often used to scare deer. Propane gas exploders, strobe lights, and even radios can be effective when deer populations are low. Another device is a motion activated sprinkler that is triggered when deer enter the garden. When activated, the sudden noise, motion, and short burst of water emitted from the sprinkler frighten animals away. Scare tactics work for only short periods of time, but may be useful by providing enough protection to allow the crop to be harvested.

Population Reduction

Population reduction by sport hunting is a cost effective, long-term solution to managing deer; however it is not often a realistic option as city ordinances prohibit hunting. Where hunting is permitted, harvest with archery equipment is a safe option and deer meat can be supplied to various charitable organizations that provide food to the disadvantaged. A number of meat processing companies provide the processing and packaging for free.

Repellents

Repellents typically reduce damage by 50 percent to 75 percent at best, and often much less. If fences are not an option, repellents that have an unpleasant taste or odor may be a suitable alternative. Area repellents utilize odors and are generally less effective than contact repellents that deter feeding through bad-tasting substances. Table 1 summarizes research results on the relative effectiveness of area and contact repellents from several sources. Many of these products are costly, and a cost-benefit analysis should be considered before application.

A number of household items are commonly used as area repellents including human hair,

bar soap, cat or dog feces, and moth balls. Most of these have shown little impact

on deer browsing in scientific research; however, human hair and bar soap can reduce

browsing up to 35 percent. The repellents that have demonstrated the best efficacy

are thiram-based contact repellents such as Chaperone and Spotrete-F and those made

with putrescent egg solids.

Repellents can reduce damage, but will not entirely eliminate damage. A deer will

eat just about anything if food resources are limited. Effectiveness will vary with

deer density, season, palatability (or attractiveness) of the target plant, and availability

of alternate foods. To be effective, repellents must be applied before deer begin

actively browsing in the affected area. Keep in mind repellents will not completely

eliminate damage and that a given method’s effectiveness will change seasonally, based

on what natural foods are available to deer. Many repellents do not weather well

and will need to be reapplied after a rain.

Table 1. Comparison of damage reduction with commonly used area or contact repellents.a

| Class of | Repellants | % Reduction of Damage |

|---|---|---|

| Area | ||

| Magic Circle (bone tar oil) | 15-34 | |

| Hinder (ammonia soaps of higher fatty acids) | 43 | |

| human hair | 15-34 | |

| bar soap | 38 | |

| blood meal | NEb | |

| cat/dog feces | NEb | |

| moth balls | NEb | |

| human sweat | NEb | |

| putrefied meat scraps | NEb | |

| Contact | ||

| Big Game Repellent (BGR) (putrescent egg solids) |

70-99c | |

| Ro-pel (Benzyldiethyl ammonium saccharide) | <15 | |

| Hot Sauce (Capsaicin) | 15-34 | |

| Thiram based (e.g., Chaperone, Spotrete-F) |

43-78 | |

-

- Use of a trade name does not imply an endorsement, other products with the same active ingredients will generally have similar results.

- NE - generally considered not effective.

- Must be reapplied one to two times per month for good efficacy

Using Deer Feeding Behavior

Deer forage or feed selectively on different plants or plant parts. Feeding habits change with the seasonal availability of plants. Deer choose different plants and plant parts based on nutritional needs, palatability, and past experience. Deer demonstrate preference for new plantings and fertilized and cultivated domestic varieties. In Oklahoma, damage to ornamentals may occur at any time of the year. However, most complaints occur in spring, in August during dry years, and after the first cold spell in fall. Under circumstances of high population density or low food availability, deer may damage plants that they otherwise would not typically feed upon. Deer also may exhibit some regionalized taste preferences.

Like humans, deer consume a wide variety of plants to meet their nutritional requirements.

Dietary and browse research in Oklahoma have documented more than 100 different species

of plants comprising a deer’s diet in a given locale. However, deer do tend to avoid

certain plants and this knowledge can be used to determine which plants to use for

landscaping and gardening. The following list details many plants used in landscaping

and in gardening by relative deer use. From this list, you should be able to choose

plants that will lower chances of damage occurring, or at least identify plants that

may require some type of protection if they are to be grown successfully.

Judicious selection of plants in combination with various control methods should provide

the rural or suburban homeowner with some realistic means of damage reduction. Remember

to begin control measures before significant damage occurs. Garden plants that suffer

rare or occasional damage when mature may suffer frequent damage at transplanting

time (e.g., peppers, corn, okra, squash). The same may be true with garden plants

that are planted early in season and again in fall. Thus, deer damage control strategies

are more effective when implemented before the growing season.

In areas with severe problems, select only ornamental plants that are less frequently

browsed by deer. Even if a combination of plants prone to browsing and those less

prone to browsing are used, damage may still occur because deer are selective feeders.

Realize that new plantings of less preferred plants may sustain damage in an area

where extensive damage has previously occurred, and that younger plants frequently

sustain damage because they are more palatable.

Finally, incorporating several tactics, such as planting resistant species, fencing

vegetable gardens, and protecting already established, browsing-prone plants with

a repellent will increase protection against deer damage. Experiment with different

tactics until you find what works best in your landscape. For additional information

on any of the above control measures contact your local county office of the Cooperative

Extension Service.

Garden Plants—Severely Damaged

| Common Name | Botanical Name | |

|---|---|---|

| Beans | Phaseolus spp. | |

| Broccoli | Brassica oleracea italica | |

| Cabbage | Brassica oleracea capitata | |

| Carrot | Daucus carota sativa | |

| Cauliflower | Brassica oleracea botrytis | |

| Kohlrabi | Brassica oleracea | |

| Lettuce | Lactuca sativa | |

| Peas | Pisum sativum | |

| Spinach | Spinacia oleracea | |

| Turnip | Brassica rapa |

Garden Plants—Frequently Damaged

| Common Name | Botanical Name | |

|---|---|---|

| Beets | Beta vulgaris | |

| Corn, sweet | Zea mays | |

| Potatoes, sweet | Ipomoea batatas | |

| Strawberries | Fragaria spp. |

Garden Plants—Occasionally Damaged

| Common Name | Botanical Name | |

|---|---|---|

| Asparagus | Asparagus officinalis | |

| Okra | Abelmoschus esculentus | |

| Potatoes, Irish | Raphanus sativus | |

| Radish | Raphanus sativus | |

| Squash | Cucurbita pepo |

Garden Plants—Rarely Damaged

| Common Name | Botanical Name | |

|---|---|---|

| Canteloupe | Cucumis melo cantalupensis | |

| Cucumber | Cucumis sativus | |

| Eggplant | Solanum melongena | |

| Hot peppers | Capsicum annuum | |

| Onion | Allium spp. | |

| Sweet peppers | Capsicum frutescens | |

| Tomato | Lycopersicon esculentum | |

| Watermelon | Citrulus lanatus |

Herbaceous Plants—Annual Flowers

Frequently Damaged

| Common Name | Botanic Name | |

|---|---|---|

| Aster | Aster spp. | |

| Impatiens | Imaptiens walleriana | |

| Morning glory | Ipomea spp. | |

| Ornamental sweet potato | Ipomea batatus | |

| Pansy | Viola spp. |

Herbaceous Plants—Annual Flowers

Rarely Damaged

| Common Name | Botanic Name | |

|---|---|---|

| Ageratum | Ageratum houstonianum | |

| Amaranth | Amaranthus tricolor | |

| Angel’s trumpet | Brugmansia spp. (Datura) | |

| Blanket flower | Gaillardia spp. | |

| Castor bean | Ricinus communis | |

| Cosmos | Cosmos bipinnatus | |

| Chinese forget-me-not | Cynoglossum amabile | |

| Cupflower | Nierembergia hippomanica | |

| Dusty Miller | Senecio cineraria | |

| Flowering tobacco | Nicotiana spp. | |

| French marigold | Tagetes patula | |

| Globe amaranth | Gomphrena globosa | |

| Heliotrope | Heliotropium arborescens | |

| Lantana | Lantana spp. | |

| Ornamental pepper | Capsicum annuum | |

| Periwinkle | Catharanthus roseus | |

| Polygonum | Polygonum capitatum | |

| Poppy | Papaver spp. | |

| Pot marigold | Calendula spp. | |

| Salvia | Salvia viridis | |

| Sanvitalia | Sanvitalia procumbens | |

| Signet marigold | Tagetes tenuifolia | |

| Snapdragon | Antirrhinum majus | |

| Snow-on-the-mountain | Euphorbia marginata | |

| Spider flower | Cleome hasslerana | |

| Stock | Matthiola incana | |

| Strawflower | Helichrysum bracteatum | |

| Sweet alyssum | Lobularia maritima | |

| Wax begonia | Begonia semperflorens | |

| Zinnia | Zinnia angustifolia | |

| Zinnia | Zinnia elegans |

Herbaceous Plants—Perennial Flowers

Frequently Damaged

| Common Name | Botanical Name | |

|---|---|---|

| Aster | Aster spp. | |

| Day lily | Hemerocallis spp. | |

| English Ivy | Hedera helix | |

| Hosta | Hosta spp. | |

| Sunflower | Helianthus spp. | |

| Tulip | Tulipa spp. |

Herbaceous Plants—Perennial Flowers

Rarely Damaged

| Common Name | Botanical Name | |

|---|---|---|

| Allium | Allium spp. | |

| Amsonia | Amsonia spp. | |

| Anise hyssop | Agastache spp. | |

| Baby’s-breath | Gypsophila paniculata | |

| Barrenwort | Epimedium spp. | |

| Basket of gold | Aurinia saxatilis | |

| Bear’s breeches | Acanthus mollis | |

| Bee balm | Monarda spp. | |

| Bergenia | Bergenia spp. | |

| Blanket flower | Gaillardia spp. | |

| Bleeding-heart | Dicentra eximia | |

| Bleeding-heart | Dicentra spectabilis | |

| Bugleweed | Ajuga reptans | |

| Butterfly weed | Asclepias tuberosa | |

| Cactus | many genera and species | |

| Candytuft | Iberis sempervirens | |

| Catmint | Nepeta spp. | |

| Chrysanthemum | Dendranthema spp. | |

| Columbine | Aquilegia spp. | |

| Coneflower | Echinacea spp. | |

| Coralbells | Heuchera sanguinea | |

| Coreopsis | Coreopsis lanceolata | |

| Coreopsis | Coreopsis verticilla | |

| Corydalis | Corydalis spp. | |

| Crocosmia | Crocosmia spp. | |

| False indigo | Baptisia spp. | |

| Flax | Linum perenne | |

| Foxglove | Digitalis grandiflora | |

| Foxglove | Digitalis purpurea | |

| Gas Plant | Dictamnus albus | |

| Gay-feather | Liatris spicata | |

| Globe thistle | Echinops exaltatus | |

| Golden marguerite | Anthemis tinctoria | |

| Goldenrod | Solidago spp. | |

| Grasses | many genera and species | |

| Iris | Iris spp | |

| Italian Arum | Arum italicum ‘Pictum’ | |

| Japanese anemone | Anemone x hybrida | |

| Japanese painted fern | Athyrium niponicum var. pictum | |

| Joe pye weed | Eupatorium purpureum | |

| Lamb’s ears | Stachys byzantia | |

| Lavender | Lavandula angustifolia | |

| Lavender cotton | Santolina chamaecyparissus | |

| Lenten rose | Helleborus spp. | |

| Lily-of-the-valley | Convallaria majalis | |

| Lungwort | Pulmonaria spp. | |

| Lupine | Lupinus polyphyllus | |

| Meadow rue | Thalictrum spp | |

| Monkshood | Aconitum spp. | |

| Narcissus | Narcissus spp. | |

| Oriental poppy | Papaver orientale | |

| Penstemon | Penstemon spp. | |

| Plumbago | Ceratostigma plumbaginoides | |

| Primrose | Oenothera spp. | |

| Purple Coneflower | Echinacea purpurea | |

| Ragwort | Ligularia spp. | |

| Red-hot poker | Kniphofia spp. | |

| Rose campion | Lychnis coronaria | |

| Rosemary | Rosmarinus officinalis | |

| Rue | Ruta spp. | |

| Russian sage | Perovskia atriplicifolia | |

| Sage | Salvia spp. | |

| Sea holly | Eryngium spp. | |

| Shasta daisy | Leucanthemum x superbum | |

| Speedwell | Veronica spp. | |

| Spurge | Euphorbia spp. | |

| Sweet woodruff | Galium odoratum | |

| Thyme | Thymus spp. | |

| Toad lily | Tricyrtis hirta | |

| Turtlehead | Chelone spp. | |

| Virginia bluebells | Mertensia pulmonarioides | |

| Wormwood | Artemisia species | |

| Yarrow | Achillea spp. |

Woody Plants—Frequently Damaged

| Common Name | Botanical Name | |

|---|---|---|

| Apples | Malus spp. | |

| American Arborvitae | Thuja occidentalis | |

| Cherries | Prunus spp. | |

| Clematis | Clematis spp. | |

| Cornelian Dogwood | Cornus mas | |

| Eastern Redbud | Cercis canadensis | |

| English Ivy | Hedera helix | |

| Hybrid Tea Rose | Rosa x hybrida | |

| Norway Maple | Acer platanoides | |

| Peaches | Prunus persica | |

| Plums | Prunus spp. | |

| Rhododendrons | Rhododendron spp. | |

| Catawba Rhododendron | Rhododendron catawbiense | |

| Evergreen Azaleas | Rhododendron spp. | |

| Winged Euonymus | Euonymus alatus | |

| Wintercreeper | Euonymus fortunei | |

| Yews | Taxus spp. | |

| English Yew | Taxus baccata | |

| Western Yew | Taxus brevifolia | |

| Japanese Yew | Taxus cuspidata | |

| Hybrid Yew | Taxus x media |

Woody Plants—Occasionally Damaged

| Common Name | Botanical Name | |

|---|---|---|

| Basswood | Tilia americana | |

| Greenspire Linden | Tilia cordata ‘Greenspire’ | |

| Beautyberry | Callicarpa spp. | |

| Border Forsythia | Forsythis x intermedia | |

| Common Witchhazel | Hamamelis virginiana | |

| Cotoneaster | Cotoneaster spp. | |

| Cranberry | ||

| Cotoneaster | Cotoneaster apiculatus | |

| Rockspray | ||

| Cotoneaster | Cotoneaster horizontalis | |

| Dawn Redwood | Metasequoia glyptostroboides | |

| Eastern White Pine | Pinus strobus | |

| Falsecypress | Chamaecyparis spp. | |

| Firethorn | Pyracantha coccinea | |

| Goldflame Honeysuckle | Lonicera x heckrottii | |

| Hollies | ||

| Japanese Holly | Ilex crenata | |

| China Boy Holly | Ilex x meserveae ‘China Boy’ | |

| China Girl Holly | Ilex x meserveae ‘China Girl’ | |

| Hydrangeas | ||

| Smooth Hydrangea | Hydrangea aborescens | |

| Climbing Hydrangea | Hydrangea anomala petiolaris | |

| Paniculated Hydrangea | Hydrangea paniculata | |

| Japanese Cedar | Cryptomeria japonica | |

| Japanese Flowering | ||

| Quince | Chaenomeles japonica | |

| Lilacs | ||

| Japanese Tree Lilac | Syringa x reticulata | |

| Late Lilac | Syringa villosa | |

| Persian Lilac | Syringa x persica | |

| Maples | ||

| Paperbark Maple | Acer griseum | |

| Red Maple | Acer rubrum | |

| Silver Maple | Acer saccharinum | |

| Sugar Maple | Acer saccharum | |

| Panicled Dogwood | Cornus racemosa | |

| Pears | Pyrus spp. | |

| Bradford Pear | Pyrus calleryana ‘Bradford’ | |

| Common Pear | Pyrus communis | |

| Privet | Ligustrum spp. | |

| Rhododendrons | ||

| Deciduous Azaleas | Rhododendron spp. | |

| Carolina Rhododendron | Rhododendron carolinianum | |

| Rosebay Rhododendron | Rhododendron maximum | |

| Rose of Sharon | Hibiscus syriacus | |

| Roses | Rosa spp. | |

| Multiflora Rose | Rosa multiflora | |

| Rugosa Rose | Rosa rugosa | |

| Saucer Magnolia | Magnolia x soulangiana | |

| Serviceberries | ||

| Downy Serviceberry | Amelanchier arborea | |

| Allegheny Serviceberry | Amelanchier laevis | |

| Smokebush | Cotinus coggygria | |

| Oaks | Quercus spp. | |

| Northern Red Oak | Quercus rubra | |

| White Oak | Quercus alba | |

| Spirea | ||

| Anthony Waterer Spirea | Spiraea x bumalda ‘Anthony Waterer’ | |

| Bridalwreath Spirea | Spiraea prunifolia | |

| Staghorn Sumac | Rhus typhina | |

| Sweet Cherry | Prunus avium | |

| Sweet Mock Orange | Philadelphus coronarius | |

| Trumpet Creeper | Campsis radicans | |

| Viburnums | ||

| Judd Viburnum | Viburnum x juddi | |

| Leather leaf Vibrunum | Viburnum rhytidophyllum | |

| Doublefile Viburnum | Viburnum plicatum tomentosum | |

| Doublefile Viburnum | Viburnum carlesii | |

| Virginia Creeper | Parthencocissus quinquifolia | |

| Weigela | Weigela florida | |

| White Fir | Abies concolor | |

| Willows | Salix spp. |

Woody Plants—Seldom Damaged

| Common Name | Botanical Name | |

|---|---|---|

| American Bittersweet | Celastrus scandens | |

| Beautybush | Kolkwitzia amabilis | |

| Buckthorn | Rhamnus spp, | |

| Chinese Junipers | ||

| (green) | Juniperus chinensis ‘Pfitzerana’ | |

| Chinese Junipers | ||

| (blue) | Juniperus chinensis ‘Hetzi’ | |

| Common Sassafras | Sassafras albidum | |

| Common Lilac | Syringa vulgaris | |

| Coralberry | Symphoricarpos spp. | |

| Corkscrew Willow | Salix matsudana ‘Tortuosa’ | |

| Deutzia | Deutzia spp. | |

| Dogwoods | ||

| Red Osier Dogwood | Cornus sericea | |

| Flowering Dogwood | Cornus florida | |

| Chinese Kousa Dogwood | Cornus kousa | |

| Eastern Red Cedar | Juniperus virginiana ‘Canaertii’ | |

| Elderberry | Sambucus spp. | |

| English Hawthorn | Crataegus laevigata | |

| European White Birch | Betula pendula | |

| Forsythia | Forsythia spp. | |

| Glossy Abelia | Abelia spp. | |

| Hollies | ||

| Chinese Holly | Ilex cornuta | |

| Inkberry | Ilex galbra | |

| Honey Locust | Gleditsia triacanthos | |

| Japanese Flowering | ||

| Cherry | Prunus serrulata | |

| Japanese Wisteria | Wisteria floribunda | |

| Kentucky Coffeetree | Picea abies | |

| Norway Spruce | Picea abies | |

| Pines | ||

| Austrian Pine | Pinus nigra | |

| Mugo Pine | Pinus mugo | |

| Red Pine | Pinus resinosa | |

| Scots Pine | Pinus sylvestris | |

| Scots Pine | Itea virginica |

Woody Plants—Rarely Damaged

| Common Name | Botanical Name | |

|---|---|---|

| American Holly | Ilex opaca | |

| Barberry | Berberis spp. | |

| Common Barberry | Berberis vulgaris | |

| Blue-mist Shrub | Caryopteris x clandonensis | |

| Boxelder | Acer negundo | |

| Butterfly bush | Buddleia spp. | |

| Buttonbush | Cephalanthus occidentalis | |

| Catalpa | ||

| Colorado Blue Spruce | Picea pungens glauca | |

| Common Boxwood | Buxus sempervirens | |

| Creeping Mahonia | Mahonia repens | |

| Drooping leucothoe | Leucothoe fontanesiana | |

| Dwarf Alberta spruce | Picea glauca ‘Conica’ | |

| Fiveleaf aralia | Eleutherococcus sieboldianus | |

| Ginkgo | Ginkgo biloba | |

| Heavenly bamboo | Nandina domestica | |

| Japanese pieris | Pieris japonica | |

| Japanese plum yew | Cephalotaxus harringtonia | |

| Leatherleaf Mahonia | Mahonia bealei | |

| Loblolly Pine | Pinus taeda | |

| Mimosa | Albizia julibrissin | |

| Oregon grapeholly | Mahonia aquifolium | |

| Osage orange | Maclura pomifera | |

| Paper Birch | Betula papyrifera | |

| Pawpaw | Asimina triloba | |

| Red yucca | Hesperaloe parviflora | |

| River birch | Betula nigra | |

| Shortleaf Pine | Pinus echinata | |

| Southern waxmyrtle | Southern waxmyrtle | |

| Spicebush | Lindera benzoin | |

| Sumac | Rhus spp. | |

| Yucca | Yucca spp. |

Acknowledgements

Revised from an earlier edition written by Ron Masters, Paul Mitchell, and Steve Dobbs. This fact sheet relied extensively on materials from Cornell Cooperative Extension, Wildlife Damage Management Program, Kentucky Cooperative Extension Service, Horticulture Magazine, February 1991, research from Penn State University, Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, Rutgers Cooperative Research and Extension, Michigan State University Extension, and personal observations and experiences of the authors in dealing with damage complaints in Oklahoma. Mike Shaw, Research Supervisor (Retired), Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation, provided numerous comments and suggestions.