Ag Insights December 2024

Sunday, December 1, 2024

Wheat Management

Josh Bushong, Area Extension Agronomist

Wheat has started to finally get some significant growth after some timely rains.

Wheat pasture prospects are still going to be limited, but now have a chance to get

well rooted and tillered prior to stocker turn-out. Unfortunately, wet conditions

are delaying the final acres to plant to the point of going past crop insurance dates.

Wheat has started to finally get some significant growth after some timely rains.

Wheat pasture prospects are still going to be limited, but now have a chance to get

well rooted and tillered prior to stocker turn-out. Unfortunately, wet conditions

are delaying the final acres to plant to the point of going past crop insurance dates.

In addition to the crop, the weeds are also starting to get established as well. Late fall and winter herbicide applications can be very beneficial to manage mustards and difficult to control winter annual grassy weeds, especially if you are going after a grain crop.

If a farmer is using one of the two herbicide-tolerant wheat systems, ie Clearfield or CoAXium, and are prioritizing weed management this year, a sequential fall followed by a spring herbicide application is our best management recommendation.

There are some concerns this year about fall applications of the herbicides for these two systems. Mainly small wheat and cooling air temperatures. Beyond herbicide, for use in Clearfield wheat, shouldn’t be applied once the max daytime temps drop below 40⁰F to reduce the risk of crop injury and it can likely reduce weed control. Also, when using a methylated seed oil (MSO) as a surfactant with Beyond, the wheat needs to have at least started to tiller for better crop safety.

As far as applying Aggressor AX, for use in CoAXium wheat, there are similar concerns. For best weed control, it is recommended to use an MSO as the surfactant, but a non-ionic surfactant (NIS) should be used for fall applications if the wheat has less than two tillers. A NIS surfactant should also be used if temperatures are expected to remain below 32⁰F following application within 30 days to prevent crop injury.

There are a couple of concerns when debating on a fall or winter herbicide application.

These include weed control, crop injury, and delayed weed emergence. If the weeds

are not actively growing, herbicide efficacy will be reduced because the plant is

going dormant and the herbicide won’t get into the plant. If waiting till spring to

avoid delayed emergence of weeds, keep in mind the weeds that impact crop yields the

most are the ones that came up with the crop.

Instead of making plans for heavy topdress nitrogen applications this winter or even

early spring, it might be more beneficial to wait later into the spring to better

estimate grain yield potential.

As far as how late can wheat be topdressed with nitrogen, field research conducted by OSU the past five seasons has shown it might be later than your think. These grain-only field trials have proven that topdress applications made 80-100 growing degree days after planting, typically early to mid-March, overwhelmingly yielded the same as early and late winter applications. Wheat quality, particularly grain protein, seemed to increase with later nitrogen applications as well.

This doesn’t mean to wait till the last minute to topdress, but this supports extending the window to apply nitrogen. Applying later in the season can increase nitrogen use efficiency. As the crop progresses, a better estimation of grain yield can be more accurately determined and topdress rates can be altered accordingly. If covering large acreage, wheat producers should initiate topdress applications sooner to allow enough time to get the job done especially if weather delays application.

Fungicide applications for disease management have shown to have good yield savings over the years. If applied timely, most commercially available fungicides have had good yield protection in OSU field trials. If only one application is budgeted, it is best to apply late and protect the flag leaf. Long-term OSU data typically average about 10 to 20 percent higher yield compared to no fungicide.

Timely field scouting is the only way to determine if a pest is present and if an application of an herbicide, insecticide, or fungicide is warranted. The only way for one of these pesticides to protect yield and have a positive return on investment would be knowing what pests are present and knowing how much yield potential can be saved if applied correctly.

Direct Impacts of Eastern Redcedar Part 2 - Eastern Redcedar Supports Expansion of Tick Populations

Dana Zook, NW OK Area Livestock Specialist

In a past article, I noted the impact of the Eastern Redcedar on forage production

and water use. This week, I wanted to highlight another area where the Eastern Redcedar

has altered our environment. OSU research has identified a link between elevated tick

populations and westward expansion of this tree species.

In a past article, I noted the impact of the Eastern Redcedar on forage production

and water use. This week, I wanted to highlight another area where the Eastern Redcedar

has altered our environment. OSU research has identified a link between elevated tick

populations and westward expansion of this tree species.

Readers may find it interesting that trees offer the perfect habitat for many tick

species by providing an elevated level of humidity present in leaf litter below the

tree. Some might also think that ticks are just a reality of life outdoors, however

tick populations have not always been as widespread. Historically, it has been thought

that the drier, more arid environment of Western Oklahoma could not support tick populations.

However, evidence of increased tick transmitted diseases across the entire state of

Oklahoma lead researchers to look more closely at where ticks were being found in

Oklahoma. Some of these tick-borne diseases include Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever,

Ehrlichiosis, and Anaplasmosis (cattle). If these diseases are being

found throughout the state, could it be that ticks are now present in the drier areas

of Western Oklahoma?

To evaluate Westward expansion of ticks in Oklahoma, OSU researchers collected ticks

in areas of both Central and Western Oklahoma in 2015. The Lone Star tick (A. americanum)

was their focus, but they also collected other species such as the American Dog Tick

(D. variabilis). Researchers found an extensive population of both the American Dog

Ticks and Lone Star Ticks in Central areas of Oklahoma (Mulhull, Norman, and near

Stillwater). These areas were once open prairie, but now host a population of many

different tree species, including the Eastern Redcedar.

To evaluate tick populations in Western Oklahoma, the study included sample sites

near American Horse Lake, Roman Nose State Park, and Klemme Range Research Station.

In these Western sample stations, researchers noted that American Dog Ticks were present

but there were low numbers of Lone Star Ticks. Because of this, researchers noted

this species may not yet be adapted to the new environmental conditions of Western

Oklahoma.

Readers are probably familiar with areas of Western Oklahoma with natural gullies

and canyons. Many areas with this landscape have fallen prey to the dense Eastern

Redcedar stands as well as many other tree species. These dense populations of trees

offer ideal habitat for these ticks to continue moving West. In this study, researchers

also note that dense trees provide habitat for other wildlife species that are reservoirs

and transporters of ticks (deer, turkeys, coyotes, etc.). Cattle and other livestock

use this area for shade and may also pick up ticks. This continues the spread causing

increased risk for tick bites in hunters and livestock producers.

Some may believe that the westward expansion of ticks is just the natural progression

of a species. Others might just accept the fact that ticks are a fact of life for

livestock producers.

Unfortunately, tick borne diseases have an enormous impact on adults and children alike. People across Oklahoma enjoy the outdoors in many ways beyond agriculture and these ticks can really impact our health and wellbeing. For assistance identifying the impact of Eastern Redcedar on rangelands, or for more information about managing ticks in livestock, contact your local OSU Extension office.

Sources:

Noden, B.H. and T. Dubie. Involvement of invasive eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana) in the expansion of Amblyomma americanum in Oklahoma. June 2017. Journal of Vector Ecology. Pages 178-183

New Ag Economic Specialist

Alberto Amador Leal Gonzalez, Area Ag Economics Specialist

Hello and welcome,

My name is Alberto Amador, recently I incorporated into the West District OSU extension

team as an Ag Economic Specialist. I’m thrilled to connect with you through this space

monthly. As an Agricultural Economist, I look forward to sharing valuable insights,

perspectives, and updates to keep you informed and engaged in the ever-evolving landscape

of agriculture and livestock economics.

There are several topics that you will expect to find in this column, tips to face emerging trends and challenges, cost-benefit analysis, reports of market trends, consumer behavior and food demand, factors influencing global and local agricultural markets, price volatility and analysis of commodity price trends, farm budgeting, accounting and financial planning, profit margin optimization, the economics of sustainable farming practices, economic impacts of climate change on agriculture, and global agricultural trade and supply chains, among others.

Let me share a bit about my background. Academically, I got a bachelor’s degree in agronomy engineering. In the last few years, I’ve pursued two graduate programs, a Master’s in Applied Economics at UPAEP in Mexico, and a Master of Business Administration (MBA) at OSU. Furthermore, I got a certificate in Agribusiness. This combination of the knowledge gathered in these programs has provided me with a holistic perspective of the agriculture and food industries. Understanding each process, a) production, b) business, and c) external factors related to industry and prices.

On the professional side, I have experience in consulting and extension in the Mexican government. I have served as an agricultural and financial consultant in my hometown, worked as a budget analyst in the Mexican federal congress, and provided consulting services to cooperatives and agribusinesses through the Secretary of Agricultural Promotion of the state of Tlaxcala, Mexico. These roles taught me valuable analytics models and effective communication strategies to explain complex topics in simple terms to stakeholders. Additionally, last summer I worked at OSU research agronomy station where I had the opportunity to visit multiple locations across Western Oklahoma for wheat harvesting.

As a farm owner, I produced corn, oats, and breed and feed lambs. My firsthand experience has given me a deep understanding of the challenges and issues that arise on a farm daily. Furthermore, I closed the lamb meat value chain selling lamb cuts and “barbacoa”, a traditional Mexican dish. During my multiple efforts to do it, I faced several challenges in production, management, and business areas. Therefore, I’ll share, through this column, information that will help you in all these processes.

In brief, I’m eager to share my experiences and contribute the knowledge I have gathered throughout my life. Please don’t hesitate to contact me through the OSU Extension office, I’ll learn from you and help as much as I can. I look forward to embarking on this journey with you- Let’s dive in.

Avian Flu Can Impact Backyard Chicken Flocks

Dana Zook, NW OK Area Livestock Specialist

Dana Zook, NW OK Area Livestock Specialist

Recent news has revealed that Avian Influenza has been detected in a commercial poultry

flock in Adair County, Oklahoma. Nationally, Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI)

has been detected in 8 states which has affected approximately 7 million birds in

the past month. More information can be accessed

on the Oklahoma Department of Agriculture website.

Since this disease has struck so close to home, I thought it would be valuable to review the precautions to take with small poultry flocks. Small flock owners may feel that this is a “big industry issue” but they couldn’t be more off base. In November alone, Avian Influenza has been detected in 27 backyard flocks across the U.S. Backyard flocks are part of the bigger picture and its possible they can contribute to the spread to the commercial poultry industry if Avian Influenza were to be detected

Some might be wondering how would Avian Flu would reach a small poultry flock? As wild birds migrate across the U.S., they fly overhead, stopping in our ponds and crop fields for rest. It’s in these situations that they are leaving behind bodily secretions and manure that can spread the disease. Free range flocks are most at risk given their ability to roam freely and access the sites that wild birds frequent. To prevent the spread of HPAI in Oklahoma, strides must be taken by poultry owners to increase biosecurity.

Here are a few tips to protect domesticated poultry from infection of Avian Influenza:

- Keep your distance from other poultry facilities and reduce visitors to a minimum. Do not borrow equipment, tools, or poultry supplies from other bird owners.

- Do not ever allow wild birds to commingle with domesticated poultry. As an added precaution, animal health officials are encouraging producers with outdoor birds to either completely confine or take steps to cover their outdoor pens for the next 30-45 days to prevent interaction with all wild birds or their manure.

- Maintain cleanliness! Clean and disinfect your hands, clothes, shoes, and equipment before and after handling poultry.

- Don’t haul the disease home. Birds coming home from a poultry show should be quarantined from the rest of the flock for 14 days. Newly purchased birds from outside sources should be quarantined for a least 30 days.

- Know the warning signs. Birds infected with HPAI may exhibit lack of energy and appetite, decreased egg production, abnormal egg shape, respiratory distress, diarrhea and swelling or purple discoloration of the head, eyelids, comb, wattles, and legs.

- Report sick birds. Contact your local county OSU Extension Office or the Oklahoma Department of Ag State Veterinarian at (405) 522-6141

No matter the size of the poultry operation, it is part of the U.S. poultry industry. As a small flock owner, you are not immune to the disease as many flocks across the U.S. have been infected. If you notice birds with the warning signs, please make a report.

Cattle Lice

Barry Whitworth, DVM Senior Extension Specialist/BQA State Coordinator Department of Animal & Food Sciences Ferguson College of Agriculture

Cattle lice costs Oklahoma cattlemen millions of dollars each year in decreased weight

gains and reduced milk production. If cattle producers have not treated their cattle

for lice this fall, they need to consider what type of lice control to initiate. This

is especially true for cattle producers that had problems in the previous year. Cattle

producers should monitor cattle closely during the months of December, January, and

February. Producers should not wait until clinical signs appear before beginning treatment.

Cattle lice costs Oklahoma cattlemen millions of dollars each year in decreased weight

gains and reduced milk production. If cattle producers have not treated their cattle

for lice this fall, they need to consider what type of lice control to initiate. This

is especially true for cattle producers that had problems in the previous year. Cattle

producers should monitor cattle closely during the months of December, January, and

February. Producers should not wait until clinical signs appear before beginning treatment.

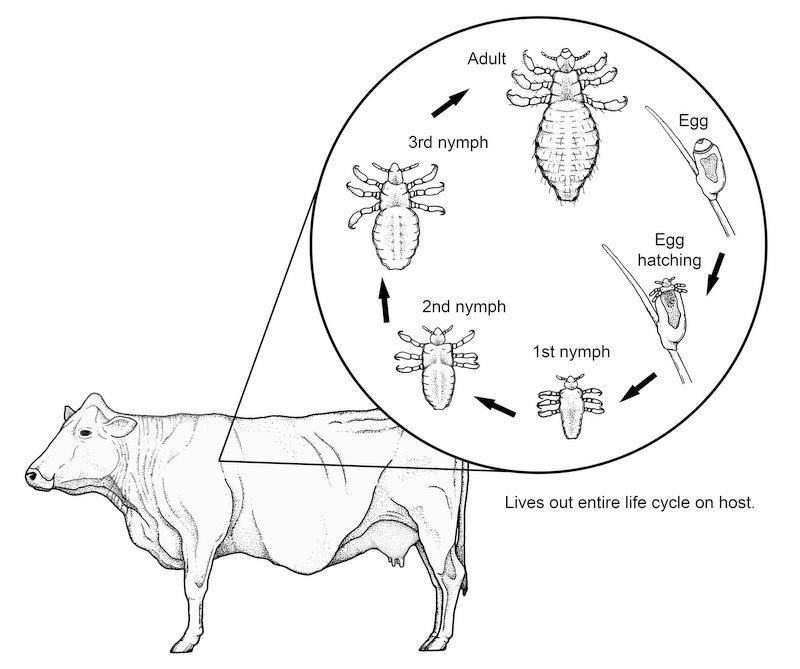

The life cycle of the different species of cattle lice are very similar. The life

cycle begins with the female louse attaching her egg to a shaft of hair. The egg will

hatch as a small replica of the adult. After several molts, the adult will emerge.

The cycle takes around 3 to 4 weeks to complete. These newly hatched lice will spend

their entire life on the host and are host specific which means cattle cannot be infected

with lice from other animals.

Small numbers of lice may be found on cattle in the summer, but high populations of

lice are associated with cold weather. Since cattle tend to be in closer proximity

to each other in the winter, lice can spread easily between cattle. A small percentage

of cattle tend to harbor larger numbers of lice. These animals are sometimes referred

to as “carrier animals”, and they may be a source for maintaining lice in the herd.

As with many other diseases, stress also contributes to susceptibility and infestation.

Signs of lice infections in cattle are hair loss, unthrifty cattle, and hair on fences

or other objects. If producers find these signs, they may want to check a few animals

for lice. They can check for lice by parting the hair and observing the number of

lice per square inch. If an animal has 1 to 5 lice per square inch, they are considered

to have a low infestation. Cattle with 6 to 10 lice would be considered moderately

infested. Any cattle with more than 10 lice per square inch are heavily infested.

Cattle have two types of lice. One type is the biting or chewing louse. These lice

have mouth parts that are adapted to bite and chew the skin. The second type is sucking

louse. These lice have mouth parts that will penetrate the skin and suck blood and

other tissue fluids. It is not uncommon for cattle to be infested with more than one

species of lice.

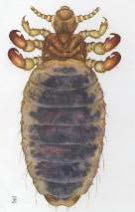

The biting or chewing louse is Bovicola (Domalinia) bovis. This type of lice feeds

on hair, skin, skin exudate, and debris. Typical clinical signs with this type of

louse are hair loss, skin irritation and scabs on the skin. They are found on the

shoulders and back.

Four types of sucking lice can be found in the United States. The first is the “short

nose” louse or Haematopinus eurysternus. This is the largest cattle louse. This louse

is found on the neck, back, dewlap, and base of the tail.

The second is the “long-nose” louse or Linognathus vituli. This louse is bluish in color with a long slender head. This louse is found on the dewlap, shoulders, sides of the neck, and rump.

The third is the “little blue” louse or Solenoptes cappilatus. This louse is blue in color and is the smallest cattle louse. This louse is found on the dewlap, muzzle, eyes, and neck.

The last is the “tail” louse or Haematopinus quadripertuses. This louse has been found in California, Florida, and other Gulf Coast States. This louse is found around the tail.

The sucking lice have the potential to cause severe anemia if the numbers are high. This can result in poor doing cattle or in extreme cases death. They also can spread infectious diseases. The long-nose louse has been found to be a mechanical vector for anaplasmosis.

| Image | Lice |

|---|---|

|

Bovicola (Domalinia) bovis |

|

Haematopinus eurysternus |

|

Linognathus vituli |

|

Solenoptes cappilatus |

|

Haematopinus quadripertuses |

Prevention of lice infestation should begin in the fall. Producers should not wait

for clinical signs to appear before beginning treatment. Several products are available

to control lice. Producers should read and follow the label directions. Producers

should keep in mind that many of the lice control products require two administrations

to control lice. Failure to do this may result in cattle having problems with lice

infestations.

Some producers have complained that some products do not work. These complaints have

not been verified; however, this is a good reason to consult a veterinarian for advice

on what products to use. Most treatment failures are associated with incorrect application

not resistance. Proper application of Pour-On insecticides is to administer from the

withers to the tailhead. Also, the proper dose is essential for good control.

Cattle producers need to consider a few other things in lice control. Since cattle

in poor body condition are more prone to lice infestation, producers need to be sure

that the nutritional needs of their cattle are being met. Cattle that have a history

of lice infestations should be culled. Lastly, any purchased cattle need to be inspected

for lice before entering the herd. If lice are found, the animals should be isolated

and treated before entering the herd.

If producers would like more information on lice in cattle, they should contact their

local veterinarian or Oklahoma State University County Extension Agriculture Educator.

They may also want to read Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Fact Sheet Beef Ectoparasites VTMD-7000.

Extension Experience – Insights into Oklahoma Agriculture

The Extension Experience podcast is brought to you by Josh Bushong and Dana Zook. Biweekly episodes provide perspectives on Agriculture topics and offer insight from our experience working with OSU Extension Educators and producers across Oklahoma.

The Extension Experience podcast is available on Spotify and Apple Podcast platforms.

You can also access the episodes on our blog.

You can also find and share our podcast from our Facebook page!

We hope you consider listening to the Extension Experience.

Recent Topics:

- The Asian Longhorn Tick w/ Dr. Johnathan Cammack

- Improving the lives of Oklahomans with ONE Health

- Heifers and Herd Expansion with Dr. Derrell Peel