Ag Insights May 2025

Thursday, May 1, 2025

Wheat Condition and Foliar Fungicide Considerations

Josh Bushong, Area Extension Agronomist

Wheat conditions are highly variable this spring. Overall stands are inconsistent, but still viable. “Spring green-up” was somewhat delayed this year, but once the wheat plants hit first hollow stem or jointing stage rapid growth has developed the past couple of weeks.

Along my travels I have noticed some chlorotic, or yellowing, in some of the wheat fields. I attributed the main potential culprits to have been either nitrogen deficiencies or response to herbicides. Crop response to nitrogen applications is always going to be determined on a field-by-field basis. While some of the crop has been under fertilized for lack of optimistic outlook reasons, I have also received reports of farmers claiming they have yet to see a response from their N-Rich strip.

As far as the crop response to herbicides, there have been a few fields where the crop has shown symptomology from applications of Acetolactate Synthase inhibitors (Group #2, Sulfonylurea & Imidazolinone). These products have been widely used in wheat for decades and a vast majority of the time farmers expect zero crop injury from using these products.

Occasionally when applications are made on stressed wheat within a couple days of cold temperatures crop injury can be found. Rarely will these instances reduce grain yield. The wheat usually recovers once growing conditions improve with more rain and warmer temperatures.

There have been a couple reports of mites throughout the region. Brown wheat mites are easiest to find in the afternoon on warm days. Wheat may show symptoms of being scorched or bronzed and withered. Treatment thresholds for an acaricide application in 25-50 per leaf on 6-9 inch plants. Heavy rainfall can reduce mite numbers significantly but will not eliminate them. Crop rotation is a good management option going forward.

I have found aphids starting to come in some fields, mostly greenbug and bird cherry-oat. Using the “Glance-N-Go” method (factsheet or phone app) is a great tool for scouting for greenbugs. Bird cherry-oat aphids typically don’t cause much visible damage to the wheat plant, but high numbers can reduce forage and grain yields. If populations exceed an average 25-30 per tiller prior to the wheat heading a 5% yield loss could occur and if populations average 50 or more a 10% yield loss could occur.

I have started to receive some questions about fungicide applications to protect the flagleaf. As with all crop protection products this year, the price and potential return on investment of fungicides is a major concern. From reviewing an eight-year data set from the OSU wheat variety trials near Lahoma, on average there was about a 20 percent yield savings comparing no fungicide versus a single flagleaf timed fungicide application. This average is across all varieties tested including those with and without adequate disease resistance.

Knowing your wheat variety and how good a disease package it is expected to have is always our first line of defense. Next is scouting and reviewing reports of diseases as they progress through the region. A fungicide application will only protect yield potential, so the decision to spray or not will ultimately depend on the risk of having the disease present.

County wheat field tours and research field days are starting later this month. The Chickasha Wheat and Forages Field Day is on April 25th and the Lahome Wheat Field Day on May 16th. There are about 18 other county wheat field tours across the state. State and area specialists will discuss wheat variety characteristics and provide agronomic updates. Oklahoma Department of Agriculture, Food, and Forestry pesticide applicator continuing education units (ODAFF CEUs) will be offered at many of the tours and field days. Please visit the Plot Tours Homepage to find the full schedule, or contact your local OSU Extension Office.

Hold Your Horses!...and Cows

Dana Zook, NW OK Area Livestock Specialist

Spring is my absolute favorite time of year. The weather warms up, I’m able to get out in my garden, and my kids go outside with minimal footwear (moms everywhere know what I mean). For my day job, spring is the beginning of a new forage production season. “Green-up” is an exciting time but it’s important to avoid grazing or haying too early. With the next grazing season around the corner, let’s review some best management practices for our native grass.

Let’s start by addressing native hay meadows. From a hay production standpoint, the key to managing native hay meadows is to maintain the balance between forage yield and forage quality (Native Hay Meadow Management, NREM-2891). Unfortunately, these two things never occur at the same time. Highest forage yield is in August while forage quality (protein and energy) peaks sometime in May. This guide recommends cutting meadows to no less than 4 inches to avoid cutting the plant growing points, which are elevated late in the season. I mention this because it is very possible to run hay-cutting equipment close to the ground and damage production potential for the plants the following year. If using native grass for hay, it’s ideal to cut in early July. Unfortunately, it’s very common to hay native meadows late in the season. This not only damages the plant structure and species diversity but also produces a low-quality hay product.

In native plant communities, 70% of the production occurs before July 1st. Whether hayed or grazed, native plant communities are slow to re-grow. That being said, optimal forage utilization within a grazing system requires a balance of early year grazing with the ability to stockpile a portion of the forages for grazing in late summer and fall. Grazing initiation is very similar to native hay meadow management. Don’t graze too early to minimize impacting future production. There is value to taking advantage of increased forage quality early in the season, however that impacts production later in the season. For this reason, it’s best to be able to utilize several different grazing areas and/or apply a light stocking rate to gain year-round or season long grazing.

The most productive livestock enterprises in our industry have a strategic plan to manage forages, utilizing annual and perennial sources for our livestock and minimizing expensive hay use. No one type of forage can be grown year-round in Oklahoma so it’s important to have diverse grazing options for a livestock enterprise.

One of the best grazing practices is to evaluate your stocking rate. Oklahoma State University Extension educators across the state are becoming more familiar with the Rangelands Analysis Platform (RAP) to evaluate stocking rate and woody encroachment. The RAP includes a stocking rate calculator that can evaluate a property for the proper stocking density. This tool can get very specific by using the animal size and grazing days to determine the average stocking rate based on historical forage production. Overgrazing doesn’t just impact one year of forage production rather, impacting the future stand of native grass for several years. If damage has occurred due to overgrazing or cutting the forages too low, producers may see a variety of undesirable plants start to grow with a loss in the native plant diversity. If you are interested in evaluating your stocking rate, look up your Extension educator for more information.

To wrap up, if you are interested in another management for range and pasture, consider attending the upcoming Musk Thistle Roundup held in Jet, OK on May 9th at 9AM. Here you can learn about the different ways to control musk thistles and then collect musk thistle weevils that you can take home and distribute in your own problem areas. To sign up and to get more information contact Alfalfa County Extension at 580-596-3131. Enjoy this spring season!

Hay Opportunity Costs

Alberto Amador, Area Ag Economics Specialist

Hay is a significant input in cow-calf operations, especially during winter or when pasture is unavailable. Precipitation in April and May is crucial in determining grazing management and hay production plans. According to the lasts report from Climate Prediction Center (CPC), there is 50-55% probability of rain above the normal precipitation levels across Oklahoma during the last week of April and first week of May. This would enhance pasture conditions for short-term grazing and hay planning for future threating scenarios. However, the broader seasonal drought outlook (April to June) indicates that drought conditions are expected to persist in Western Oklahoma.

Despite in the last few years drought has been constant, Oklahoma has remained a significant contributor to national hay production, especially, in the “other hay” category (excluding alfalfa and alfalfa mixes). As consequence, in the last decade Oklahoma’s hay supply covers the local consumption needs.

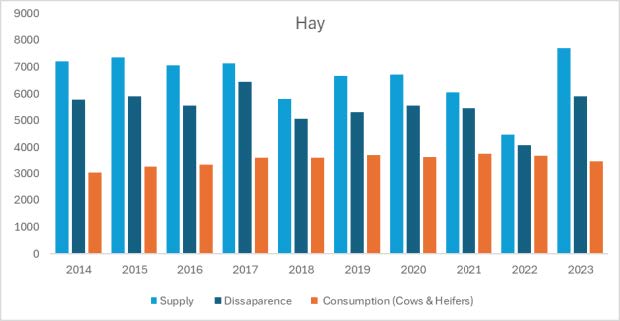

Figure 1. Hay Supply, Disappearance & Consumption

Source: Livestock Marketing Information Center

Figure 1 illustrates total hay supply, disappearance, and projected consumption (by cows and heifers) over the last decade. Although calculating the difference between consumption and disappearance, there is not enough data to determine the portion of hay used by other livestock, sold off-farm or wasted.

During my trips across Western Oklahoma, usually I see a significant number of hay bales along roadsides. Even though producers plan to use those bales at some point, those bales are losing quality and monetary value. Therefore, understanding the true economic costs of bailing hay is crucial. Knowing these costs allows producers make informed decisions about whether to purchase or produce hay and to recognize the economic loss when hay bales are wasted on the field. Even without fertilizer application, forage crops consume soil nutrients. Hence, to know the real cost of producing one ton of forage, producers should determine the nutrients requirements per ton and multiply by local fertilize prices. OSU’s factsheet AGEC-338 is a great source for this analysis.

In addition to nutrients, opportunity costs related to harvest and post-harvest practices, and land use must be considered in the costs of hay. Even if producers are doing some or all the harvest operations, I suggest using local custom rates as a baseline to know the on the local custom rates, to estimate the opportunity costs of harvest operations. In the same way, even if the land is owned, producers should account for land opportunity costs, specifically, the income they could earn by leasing the land. A good source for custom rates in the different regions of Oklahoma is the OSU’s factsheet CR-205.

| Costs | $/Bale | $/Ton |

|---|---|---|

| Fertilizer | $12.50 | $17.50 |

| Machinery and Equipment | $34.00 | $48.00 |

| Land | $14.30 | $20.00 |

| Total | $60.80 | $85.50 |

As an example, I’ve calculated bale and ton costs based on 1 ton of Bermuda grass per acre, with a bale weight of 1400 pounds, and 7.8% of crude protein. The results are summarized in the table above. However, it’s important to keep in mind that the price index for haying machinery and equipment has increased 35% since 2021, when the custom rates were collected. To get an accurate cost estimate for hay production, I suggest reaching out to neighbors or local service provider to use update and local custom prices. In addition, if you need assistance with your calculations don’t hesitate to visit your extension county office. We’ll be glad to help you.

April Showers May Bring Parasitic Problems

Barry Whitworth, DVM

Senior Extension Specialist/BQA State Coordinator, Department of Animal & Food Services,

Ferguson College of Agriculture, Oklahoma State University

According to Gary McManus, State Climatologist with the Oklahoma Mesonet, April 2025 brought one of the highest average rainfalls in the state’s history. With warm temperatures likely to follow in May, the environment will be perfect for the proliferation of Haemonchus contortus, better known as the barber pole worm. This blood-feeding nematode targets small ruminants like sheep and goats. Its name stems from the red-and-white spiral pattern of the adult worm, which inhabits the abomasum (the fourth stomach compartment) of its host. If left unchecked, the parasite can cause anemia, weight loss, bottle jaw, poor production, and death—especially in young animals.

The lifecycle of the barber pole worm has three stages: the development stage, the prepatent (pre-adult) stage, and the patent (adult) stage. The development stage occurs in the environment and begins when the eggs are excreted in fecal pellets. The ideal temperature for this stage ranges from 70°F to 80°F, but any temperature above 45°F will allow for development. Temperatures above 85°F or below 45°F will begin to hamper development. Humidity needs to be 80% or higher. The egg hatches into a first-stage larva (L1). L1 molts (sheds its cuticle or skin) to become L2. L1 and L2 survive by eating bacteria in the feces and soil. They are susceptible to dying in cold, hot, and dry conditions. L2 molts to L3, which has a protective sheath and is less susceptible to the elements. L3 is the infective form of the parasite. L3 must have moisture to free itself from the fecal pellet. Once free, it rides a wave of water onto a blade of grass, reaching a height of 2 to 3 inches. Once ingested, this begins the prepatent (pre-adult) stage.

Inside the body, L3 migrates to the abomasum. Two molts take place (L3 to L4 and L4 to L5). If environmental conditions are not favorable for the survivability of the parasite’s offspring, L4 will enter an arrested development stage (hypobiosis) for a period of time. During hypobiosis, the parasite is metabolically inactive, making it somewhat resistant to anthelmintic (dewormer) treatment. Once environmental conditions outside the body become more favorable for egg hatching and larval survival, L4 molts to L5, which matures into an adult. This is the patent (adult stage).

Haemonchus contortus resides in the abomasum, where it feeds on blood. Unless controlled, the parasite will drain the animal of its blood, resulting in anemia, weakness, and hypoproteinemia (low blood protein levels). Clinical signs in animals with heavy burdens include pale mucous membranes, bottle jaw (edema or swelling under the jaw), weight loss, lethargy, poor performance, and, in extreme cases, death. Young animals are especially prone to dying.

If an animal displays clinical signs consistent with parasitism, a fecal egg count should be performed to confirm the diagnosis. Animals that have died can be necropsied. During a necropsy, a veterinarian will examine the abomasum for worms. These worms are small and thread-like with the characteristic red-and-white banded appearance.

Producers should monitor their flocks for parasitism at all times, especially when conditions are ideal for the parasite. Several methods can be used. A fecal egg count (FEC) is a good way of assessing parasite burdens. Another monitoring method is checking eye scores (FAMACHA). FAMACHA checks for anemia by observing the membranes around the eye for paleness. The Five-Point Check uses FAMACHA and four other observations to assess parasite burdens. These four other observations are body condition score (BCS), dag score (fecal soiling of the tail), hair coat (appearance), and jaw (bottle jaw). If producers are unfamiliar with any of these methods, they can learn more about them at the American Consortium for Small Ruminant Parasite Control Website.

Small ruminants diagnosed with parasitism will need to be treated. Many of these animals will require supportive care in addition to receiving an anthelmintic drug (dewormer). Unfortunately, anthelmintic drug resistance is a major issue with the barber pole worm. Small ruminant producers should consult with their veterinarian for the best treatment options.

Since anthelmintic drug resistance is a serious problem, the barber pole worm must be managed through an integrated parasite management (IPM) approach. IPM utilizes several different management techniques to control the parasite. For more information on best management practices for controlling the barber pole worm, producers should visit the Best Management Practices to Control Internal Parasites in Small Ruminants Factsheet Series page.

Haemonchus contortus is a major health issue for small ruminants, especially in warm climates. Effective control requires a multifaceted approach combining good management practices, selective dewormer treatment, and careful monitoring. With anthelmintic drug resistance a major issue, small ruminant producers will need to rely on long-term control strategies and be less reliant on drugs to solve this issue. For more information on the barber pole worm, small ruminant producers should consult with their local veterinarian and/or their local Oklahoma State University Cooperative Extension County Agriculture Educator.