About Patch Burning

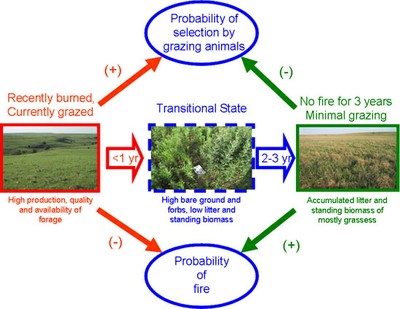

Patch burning is the purposeful grazing of a section of an landscape or management unit that has been prescribed burned, and then burning another section to move the grazing pressure, thus creating a shifting mosaic on the landscape or management unit (Figure 3). Patch burning allows livestock to freely select the most recently burned part of a unit or pasture. Livestock spend 75% of their time on these patches and typically evenly utilize all the palatable plants within the entire burned patch. Then within 6-12 months burn another portion of the unit. This will shift the focal grazing point to the new burn patch. After the heavy utilization (1.5-2.5 years post burn) a transition state of bare ground, forbs, and low amounts of standing biomass and litter occurs. Within 2.5 -3 years post burn the patch receives very little grazing pressure, which allows biomass and litter to accumulate (Figure 3). This patch is then ready to be burned and grazed again. This is all accomplished without fences or other management input besides the use of prescribed fire.

Figure 3. Patch burning is the purposeful grazing of a section of an landscape or management unit that has been prescribed burned, and then burning another section to move the grazing pressure, thus creating a shifting mosaic on the landscape or management unit.

Caption: Cattle spend 75% of the time grazing on the most recently burned patches. This allows the other patches to recover. Photo Samuel D. Fuhlendorf.

Why Implement Patch Burning?

In several of the comparisons between patch burning and traditional management, no differences were found between the two practices. So, if patch burning and traditional management do not differ, why use patch burning?

We have found we can achieve more consistently the following outcomes with patch burning than with traditional management:

- Dependable use of prescribed fires

- Greater fuel loads for prescribed burning

- Ability to use prescribed burning without deferring grazing before burning

- Does not require gathering or moving cattle before burning

- Control of invasive plants without chemical or mechanical methods

- Creation of a heterogeneous landscape that provides economic, environmental, and ecological benefits

- Provides rest for each portion of a pasture for 2 to 3 years

- Achieve uniform distribution of grazing use over the entire pasture (over a period of years)

- Manage for drought by stockpiling forage

- Requires feeding less protein supplement in the winter

- Provide habitat for species of wildlife native to grassland, shrublands or forestlands

With patch burning all of the above mentioned benefits are attainable. So remember there may be several aspects of patch burning that show no difference to traditional management, but the overall benefits to the land and animals that use it are greater with patch burning.

With patch burning, land managers can control invasive plants without chemical or mechanical methods, create a heterogeneous landscape that provides economic, environmental, and ecological benefits, rest each portion of a pasture for 2 to 3 years, and achieve uniform distribution of grazing use over the entire pasture (over a period of years). Photo Stephen Winters.

How to Implement Patch Burning

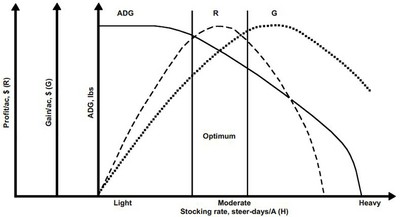

Selecting the proper stocking rate on the unit is the most important step when planning a patch burn program. Most land managers believe that “more is better”, but research demonstrates that maximum net return/acre occurs at a moderate stocking rate (Figure 17). For the benefit of livestock, plant community, and wildlife, proper stocking rate is crucial. Stocking rate is also important in patch burning because once patch burning is implemented, grazing is not deferred either before or after burning, and the livestock are left on the pasture the entire time (even while burning). Therefore, the proper stocking rate will provide two contrasting patch types: 1) a grazing lawn in the most recently burned patch, and 2) ungrazed grasses in the patch with the greatest time since the last burn (least recently burned patch). If stocking rate is too light, a grazing lawn will not occur in the most recently burned patch (i.e., the grass will be too tall to qualify as a “lawn”). If stocking rate is too heavy, grazing will occur in the least recently burned patch, and in the extreme, this patch will not carry a fire.

The next decision is to determine the fire return interval. In areas of higher rainfall (30+ inches per year), a fire return interval of three years has been used effectively. While in drier regions, a four year fire return interval might provide better results.

Once the fire return interval has been determined the land manager may want to consider burning in different seasons of the year. Growing season burns can be very beneficial for wildlife and livestock. For example, we found that a cow-calf enterprise can benefit with burning in both the dormant and growing season because the contrasting burn seasons provides patches with higher quality forage during these different times of the year.

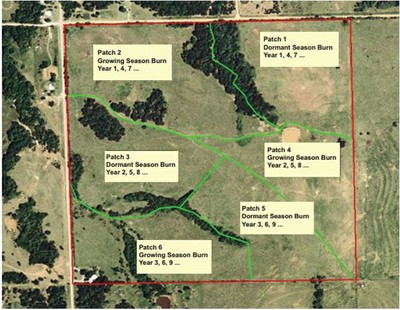

After deciding on fire return interval and burning season, simply divide the pasture into the appropriate number of burn units. For example (Figure 18), for a three year fire return interval and burning in the both the dormant and growing season, divide the pasture into six patches. The patches do not have to be the exact same size, and patch boundaries can utilize existing county or pasture roads, creeks, or other natural barriers to reduce fire break construction and to facilitate safer and easier burning.

Figure 17. Selecting a proper stocking rate is the most important decision when implementing patch burning. Most land managers believe that “more is better”, but research demonstrates that maximum net return per acre occurs at a moderate stocking rate.

Figure 18. An example of patch burning designed for a three-year fire frequency and two burning seasons. This design uses existing pasture roads, creeks, and some establishment of permanent lines for fire breaks.

Frequently Asked Questions & Other Resources

There are many questions land managers have about patch burning, such as what season and frequency of burning (fire return interval) is required in patch burning? With the answer depending upon the goals and objectives of the land manager.

-

How large/small an area will it work on?

Currently there have been patch burn studies conducted on units as small as 100 acres to areas over 20,000 acres in size. The results are all similar and have found many positive benefits of PB no matter the size of the unit.

-

Will patch burning work in more arid parts of the country?

Patch burning has been conducted in areas with over 36 inches of annual rainfall to places that receive less than 18 inches of precipitation annually. In drier regions you may want to have a longer fire return interval, which coincides with fuel build-up. Patch burning conducted in these arid sections of the country has shown benefits to vegetation and wildlife, along with no differences on livestock production when compared to traditional management practices of the area. Historically fire occurred in all parts of the US, and if there was fire, grazing also occurred on these sites. Grazing may have not been carried out by large herbivores such as bison, but numerous other grazing animals of smaller size utilized these burned sites.

-

Will patch burning work on reconstructed prairie or “go back lands”?

Yes, patch burning will work on these sites as well. The native vegetation that has been planted or allowed to grow back are the same species that occurred there historically and are very adapted to fire and grazing at the proper stocking rate.

-

Does patch burning require buffalo to work?

Granted bison are the symbolic native ungulate we think of concerning the fire-grazing interaction, but with the proper stocking rate patch burning has been shown to work very well with either stocker cattle or cow/calf enterprises. At this time there has been no work done with other domestic livestock such as goats or sheep. But with the proper stocking rate, these animals should fit very well into the patch burning program.

-

Can mowing be used effectively to replace grazing?

One of the values of grazing is that it is selective, and both bison and cattle select strongly for grasses. Mowing is nonselective so the effects on vegetation differ from the effects of grazing. If grazing is out of the question, mowing might partially replace the effects of grazing, but it is important to recognize that prairie evolved under the interacting influence of fire and grazing, not fire and mowing.

-

What season and frequency of burning (fire return interval) is required in patch burning?

This depends upon the goals and objectives of the land manager. Burning in two different seasons of the year will create more diversity. Fire frequency depends upon climate and rate of fuel accumulation. One approach is to determine the historic fire return interval for your area and use it as a starting point. If you have large accumulations of fuel and the most recently burned patch is not grazed heavily, increase fire frequency. On the other hand, if fuel loads are light and there is excessive grazing pressure on all of the patches, decrease fire frequency.

-

What stocking rate of cattle is required for successful application of patch burning?

Stocking rate is generally expressed as animal units (cows, steers, etc.)/unit of land area/unit of time, while carrying capacity is the stocking rate that is sustainable over a long period of time. The main question should be, how well does your stocking rate agree with the carrying capacity of the land. Moderate stocking rate fits this description, and moderate stocking results in sufficient fuel to carry a fire.

-

Will patch burning work on CRP, WRP, and introduced pasture grasses?

The full effects of patch burning will not be seen without grazing, but the use of patch burning in set-aside grasslands like CRP and WRP can help suppress woody plant encroachment, assist nutrient cycling, and create some diversity among plants and wildlife. If set-aside grasslands can be grazed, and WRP often allows grazing, patch burning should be effective. Introduced pastures are designed to be a monoculture, with managers working to keep them uniform with grazing systems, herbicides and fertilizers. So trying to create heterogeneity in a homogenous system is counter intuitive. Still, using patch burning to create structural heterogeneity in these might have some value for some grassland wildlife species including songbirds.

-

What size should the burn patches be?

This depends on your management objectives and logistical constraints. For example, if you were trying to maximize useable space for Northern Bobwhite, 100 acre patches would not be ideal. The home range of quail is normally smaller than this, and since quail require various vegetation structures within their home range, you would want to have smaller patches. Therefore, five 20 acre patches would be preferable. However, this size may not be logistically feasible depending on the landscape, topography, firebreak locations, equipment and personnel available. A compromise might need to be met that will benefit the species managed for, but also be feasible for the land manager. Other species of wildlife will have different optimum patch sizes. If a land manager is trying to promote wildlife diversity, then various patch sizes might be most appropriate, assuming enough land is available.

- Patch Burning Research & Demonstration Areas

Iowa

- Grand River Grasslands

- Iowa River Corridor (Iowa Department of Natural Resources)

- Neal Smith National Wildlife Refuge

Kansas

Minnesota

Missouri

Nebraska

South Dakota

Texas A&M

South Africa

- Resources

Journal Articles

- Cummings, D.C., S.D. Fuhlendorf, and D.M. Engle. 2007. Is altering grazing selectivity of invasive forage species with patch burning more effective than herbicide treatments? Rangeland Ecology and Management 60:253-260

- Anderson, R.H., S.D. Fuhlendorf, and D.M. Engle. 2006. Soil nitrogen availability in Tallgrass Prairie under the fire-grazing interaction. Rangeland Ecol Mange. 59:625-631.

- Kerby, J. D., S. D. Fuhlendorf, D.M. Engle. 2006. Landscape heterogeneity and fire behavior: scale-dependent feedback between fire and grazing processes. Landscape Ecology 22:507-516.

- Vermeire, L.T., R.B. Mitchell, S.D. Fuhlendorf, and R.L. Gillen. 2004. Patch burning effects on grazing distribution. J. Range Manage. 57:248-252.

- Fuhlendorf, S.D., and D.M. Engle. 2004. Application of the grazing-fire interaction to restore a shifting mosaic on tallgrass prairie. Journal of Applied Ecology 41:604-614.

- Fuhlendorf, S.D., and D.M. Engle. 2001. Restoring heterogeneity on rangelands: ecosystem management based on evolutionary grazing patterns. BioScience 51:625-632.

- Coppedge, B.R. and J.H. Shaw. 1998. Bison grazing patterns on seasonally burned tallgrass prairie. J. Range Manage. 51:258-264.

- Coppedge, B.R., D.M. Engle, C.S. Toepfer, and J.H. Shaw. 1998. Effects of seasonal fire, bison grazing and climatic variation on tallgrass prairie vegetation. Plant Ecology 139:235-246.

- Coppedge, B.R., D.M. Leslie, and J.H. Shaw. 1998. Botanical composition of bison diets on tallgrass prairie in Oklahoma. J. Range Manage. 51:379-382.

Theses & Dissertations

- Vermeire, Lance T. 2002. The fire ecology of sand sagebrush-mixed prairie in the southern Great Plains.

- Kerby, Jay D. 2002. Patch-level foraging behavior of bison and cattle on tallgrass prairie. Oklahoma State University. M.S. Thesis. 69 p.

- Tunnell, Timothy R. 2002. Effects of patch burning on livestock performance and wildlife habitat on Oklahoma rangelands. M.S. Thesis. Oklahoma State University. 49 p.

- Roper, Aaron. 2003. Invertebrate response to patch-burning. M.S. Thesis. Oklahoma State University. 54 p.

- Harrell, Wade C. 2004. Importance of heterogeneity in a grassland ecosystem. PhD Dissertation. Oklahoma State University. 114 p.

- Townsend, Darrell E. 2004. Ecological heterogeneity: Evaluating small mammal communities, soil surface temperature and artificial nest success within grassland ecosystems. Oklahoma State University. PhD Dissertation. 162 p.

- Anderson, R.A. Hunter. 2005. Effects of fire and grazing driven heterogeneity on N cycling in tallgrass prairie.

NREM-OSU Extension Publications

- Patch-Burning: Rotational Grazing Without Fences

- E-998 - Patch Burning: Integrating Fire and Grazing to Promote Heterogeneity

Other Articles

- Preliminary effects of Patch-Burn Grazing on a High Diversity Prairie Restoration

- Patch Burn Grazing: Benefits for both Wildlife Habitat and Livestock Performance

- Patch Burning: Using Fire and Grazing to Restore Diversity in Prairie

- Tallgrass Prairie Patch Burn Grazing Brochure - TNC & NPS