Cow-Calf Corner | January 12, 2026

Beef Imports Update

Derrell S. Peel, Oklahoma State University Extension Livestock Marketing Specialist

The latest release of shutdown-delayed trade data provides information on beef and cattle imports and exports through October 2025. Beef imports have been a particular focus in industry and politically for several months.

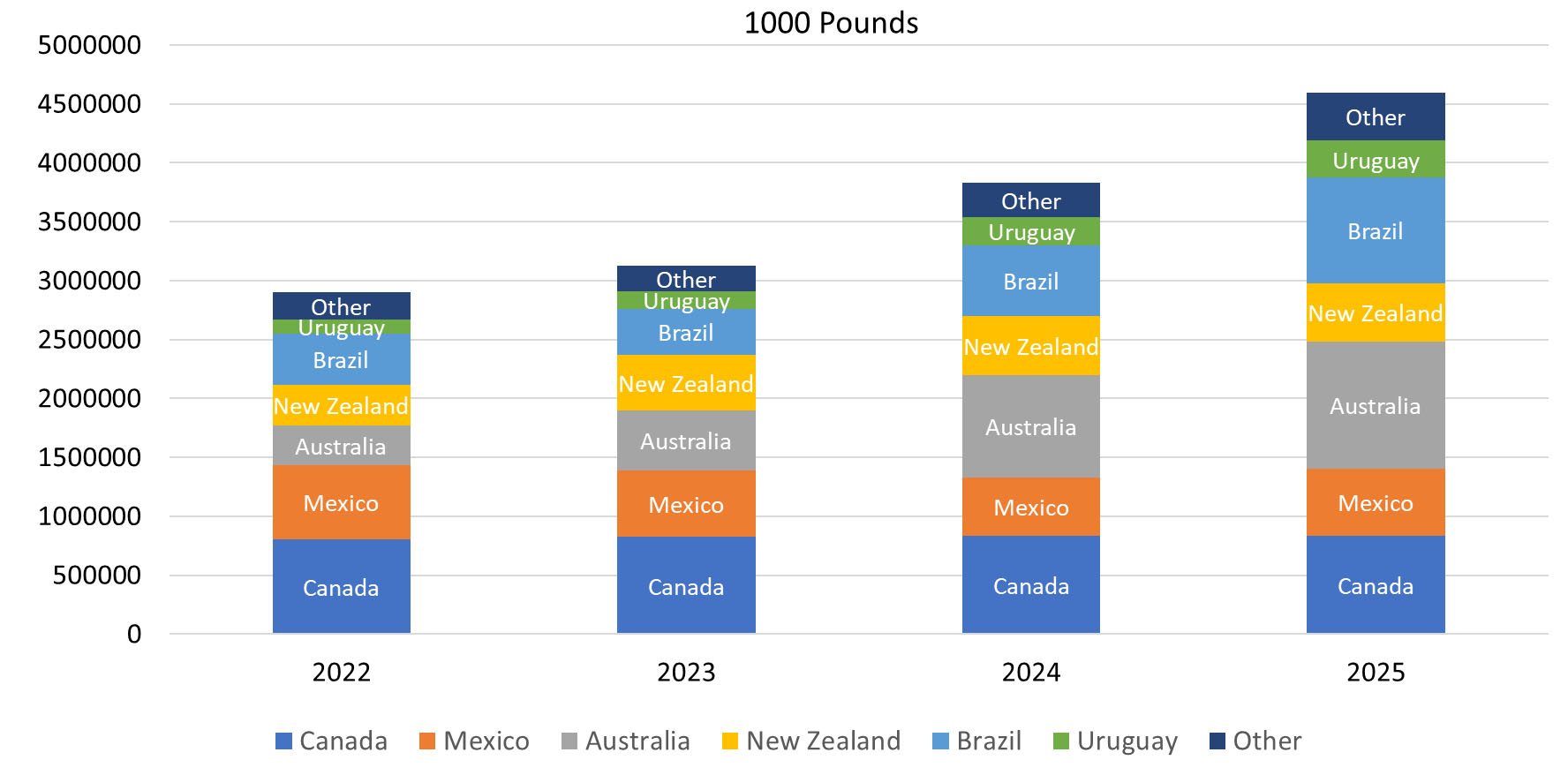

For the first ten months of 2025, beef imports were up 20.0 percent year over year (Figure 1). This follows a 24.4 percent year over year increase in 2024. Increased beef imports are the expected market response to declining beef production in the U.S., especially decreased production of nonfed processing beef. Through 2025, U.S. cow slaughter is projected to be down a total of 29.2 percent from the recent peak in 2022. Beef imports have increased to partially mitigate the resulting decreases in lean processing.

Through October, Australia was the largest source of U.S. beef imports with a 23.6 percent share of total imports. Number two Brazil accounted for 19.5 percent of beef imports, followed by Canada (18.2 percent share), Mexico (12.3 percent share), New Zealand (10.8 percent share), and Uruguay (6.8 percent share). Despite much political focus on Argentina in the fourth quarter of 2025, Argentina only represents about 25 percent of the “Other” category in Figure 1, representing 2.2 percent of total beef imports.

Figure 1. Beef Imports, January-October

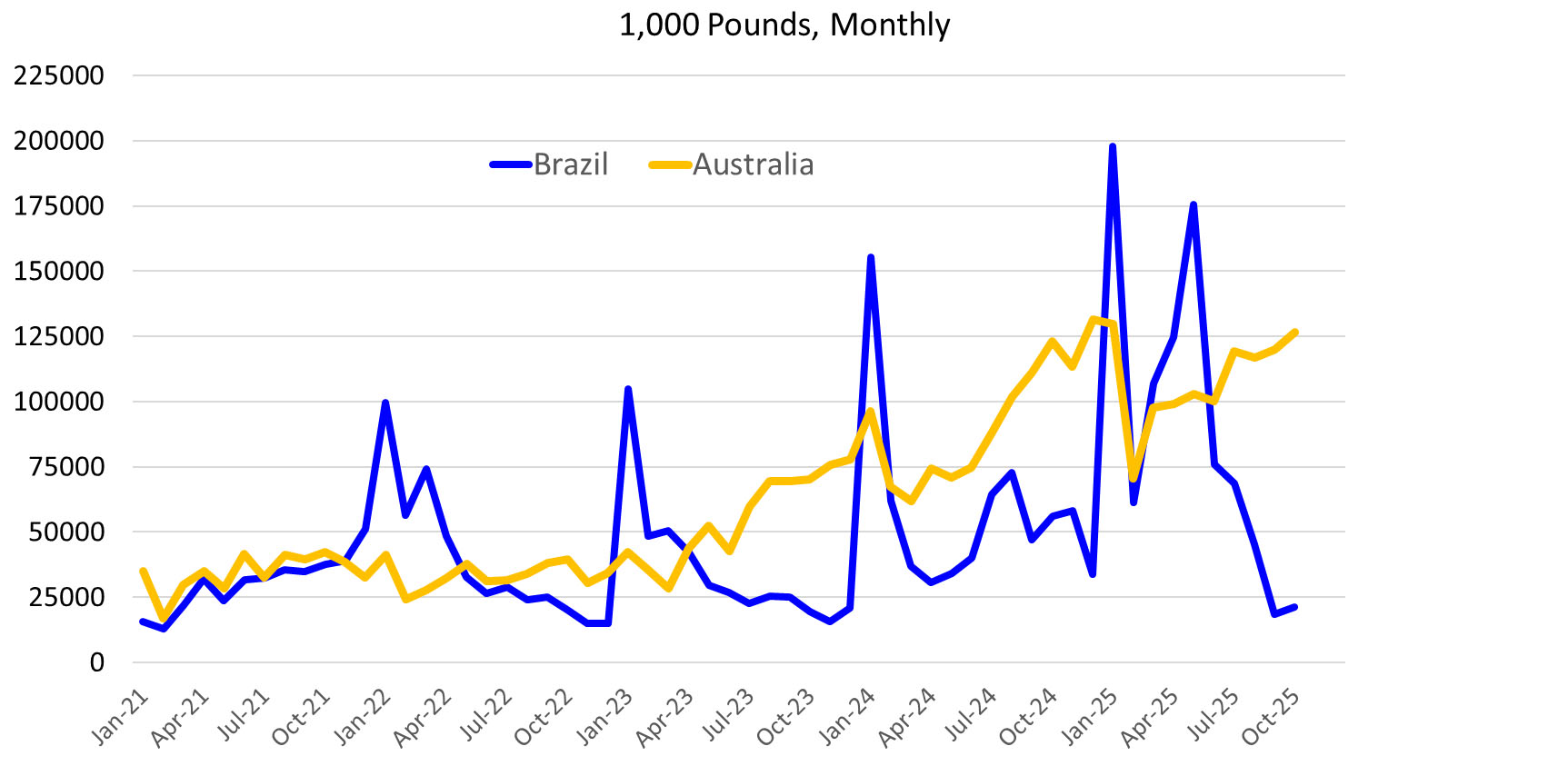

Figures 1 and 2 shows the dramatic increase in beef imports from both Australia and Brazil since 2022. Figure 2 also illustrates the dramatic difference in the seasonal pattern of beef imports from the two countries. Beef imports from Brazil are included in the “Other Country” quota. Since 2022, Brazil has moved quickly in January of each year to fill the “Other Country” quota before being subject to over-quota tariffs. The January spikes in imports of Brazilian beef are obvious in Figure 2. In 2025, a second peak in beef imports from Brazil occurred in May as market values stimulated additional imports despite the over-quota tariffs and additional 10 percent tariffs imposed in April. However, an additional 40 percent tariff imposed on Brazil in August did result in sharply lower imports from Brazil in September and October. By the end of November, all the of the additional tariffs have been removed leaving Brazil with only the over-quota tariff (26.5 percent) for the remainder of the year.

Figure 2. Beef Imports from Australia and Brazil

So far in January 2026, Brazil is moving quickly to fill the “Other Country” quota in the first two weeks of the year with zero tariff. Subsequent imports from Brazil going forward will be subject to the over-quota tariff. Once again, data will eventually confirm a spike in total beef imports in January as a result. Despite this, the domestic price of 90 percent lean trimmings in the first full week of January was $401.71/cwt., up 19.8 percent from the same period one year ago.

Derrell Peel breaks down the major drivers behind this year’s market volatility — and shares what producers can expect heading into 2026 on SunUpTV from January 5, 2026.

Leasing Bulls

Mark Z. Johnson, Oklahoma State University Extension Beef Cattle Breeding Specialist

As follow up to “What’s a Good Bull Worth in 2026?” from last week, I address a recent question from a producer regarding the cost of leasing bulls. One potential way for a commercial cow-calf operation to reduce expenses is to lease, rather than own, a bull. Producers should compare the costs and benefits of leasing versus owning. Leasing eliminates the capital expenditure of purchasing a bull. The cost of purchasing a bull (or bulls) was addressed last week. Whether leasing or purchasing bulls, the expense will be highly dependent on the cattle market and quality of the bull. A leased bull is usually kept only during the breeding season so maintenance costs associated with bull ownership are reduced. For example, the cost of feeding a bull is realistically at least $1 per day. In addition, veterinary and medicine, labor, potential death loss, the facilities needed to keep bulls safe and secure during the off-season as well as depreciation and interest. All these things considered, bull ownership has a price tag of several hundred dollars annually when bulls aren’t breeding cows.

On the other hand, leasing bulls may not be an option. Commercial cow-calf operations need to plan in advance of breeding season checking with seedstock vendors to make sure they are in the bull leasing business and will have bulls available for lease when needed. If seedstock producers are receptive to bull leasing, both the lessor and lessee need to consider how leasing a bull could affect the health of the herd. Leasing virgin bulls is ideal to ensure that a venereal disease such as vibriosis or trichomoniasis is not introduced into the lessee’s herd. A negative test for trichomoniasis (at very least) is a standard part of the lease agreement before the leased bull can be returned to the lessor’s herd. In addition, leasing bulls does not come with the benefit of the salvage value when older bulls are sold. Other considerations of a typical bull lease agreement for the benefit of both parties should include:

- A daily, monthly or breeding season fee. These fees typically start at $25/day depending on the quality and genetic value of the bull(s). Lessor would guarantee a bull has passed a breeding soundness exam.

- A value per pound of bull weight loss during the lease. This typically is based on the cost of regaining the weight after bull is returned. In the current market, $1/pound is reasonable. Both parties should agree on a reasonable weight loss and cost of regaining the weight and include this in the lease agreement.

- Cattle mortality insurance to protect the lessor (bull owner) from death loss. Both parties should agree on the value of the bull. Typically the lessee would purchase a policy covering the value of the bull, pay the premium and the policy would be paid to the lessor in the event of the bull’s death. Currently, a 60-day policy could be purchased for 3.5%, a 90-day policy could be purchased for 4% of the established value of the bull.

- Health. Typically, a negative test for trichomoniasis at completion of the lease and prior to the bull’s return, is a standard part of the lease agreement. This cost (usually $50 - $100), is covered by the lessor.

Given the current circumstances, what is the realistic cost of leasing a 15 month old bull, valued at $10,000, assumed to lose 100 pounds during the lease, at $25/day for a 60 day breeding season?

Breeding Fee: $25 x 60 days = $1,500

Weight Loss: 100 pounds x $1 per pound cost of gain = $100

Insurance: $10,000 x 3.5% = $350

Trichomoniasis Test = $75

Total = $2,025*

*In the current market, based on the quality and genetic value of the bull, prices will vary.

So assuming the 15 month old bull will cover 15 cows/heifers during the breeding season, the cost per female bred is $135. How does this compare to owning bulls? The following chart assumes a bull provides service until the age of 6. It serves as another way to evaluate the cost per female bred, based on various purchase prices of ownership.

Bull Purchase Price: $5,600 $8,400 $11,200 $14,000

$40 $60 $80 $100

Cost per female bred - assuming 140 calves sired over duration of time as a herd bull.

Dr. Mark Johnson, OSU Extension beef cattle breeding specialist, revisits the annual topic — What is a good bull worth in 2026? on SunUpTV from January 9, 2026.

Maintaining Calf Productivity When Wheat Pasture is Short

Paul Beck, Oklahoma State Extension Beef Cattle Specialist

Prospects for wheat pasture started off in good shape this fall with many areas getting rain through the summer leading up to planting. Most of the wheat grazing areas did not get adequate rains to push the emergence and growth of wheat pasture for most of the month of September and October, so if pastures were not planted into the moisture in September emergence were severely delayed. Most of the region got nice rains that will likely drive enough forage production on early planted wheat for grazing in November but veery little more until last week. Later planted wheat or wheat that had not emerged from earlier plantings will probably be severely delayed even with the latest round of precipitation in October.

What can we do to sustain stocking rates that will support at least approaching our normal levels of production?

Research from the OSU Wheat Pasture Research Unit at Marshall showed that providing a concentrate supplement (based on either corn or a soyhull/wheat middling blend) containing monensin at 0.65 to 0.75% of body weight (for example, 4 pounds per day for a 533-pound steer) increased potential stocking rate by 33% and weight gains by 0.3 pounds per day. This supplementation program can also be used to “stretch” wheat forage when pastures were 60 to 80% of normal, allowing for “normal” stocking rates.

Although intake of low quality roughages is not high enough to offset wheat forage intake and can reduce performance of growing calves. Research has shown that offering moderate or high quality roughages such as corn silage or sorghum silage or high quality round bale silages can be used to replace short wheat pasture or double stocking rates on wheat pastures. In the 1980’s research showed that feeding silage daily to calves on wheat pasture allowed stocking rates to be increased by up to 2X without reducing steer performance. When faced with short wheat pastures on some research fields a few years ago, we used this research to keep calves on short wheat pastures using round bale bermudagrass silage. Several of our fields had normal forage yields of 2500 pounds of forage per acre, where we grazed during the fall and winter with 1 calf per acre with forage allowance of 4 pounds of wheat per pound of steer and had gains of 3.3 lbs/day. Other fields were planted later and only had 70% of normal (1800 pounds of forage per acre) that we stocked at 1.5 steers per acre (forage allowance of 2.1 pounds of forage per pound of steer) and fed free-choice round bale bermudagrass silage (14% CP and 56% TDN) weekly. Even with higher stocking rates and less forage per acre these steers gained 2.6 pounds per day and total gain per acre increased from 250 for our ‘normal’ production to 300 pounds per acre. This only took about 4.5 pounds of silage dry matter per pound of added gain per acre.

Using high quality, palatable hays or silages can be used to stretch wheat pastures when concentrate feeds are expensive. So, with the large amount of hay produced last summer, this can be an economical way to maintain production of calves when wheat pasture is limited.

Brian Pugh, OSU Extension Pastures and Forages Specialist, and Paul Beck, OSU Extension Beef Cattle Nutrition Specialist, discussed proven strategies for wheat pasture management on Rancher’s Thursday Webinar Series from November 6, 2025.