Cow-Calf Corner | October 27, 2025

The Source of High Cattle and Beef Prices

Derrell S. Peel, Oklahoma State University Extension Livestock Marketing Specialist

High cattle and beef prices are suddenly receiving intense scrutiny from politicians, consumers and the media. While it seems to many that the situation has only recently happened, it has, in fact, been developing for several years. The beef cow herd on January 1, 2025 was 27.86 million head, down 3.78 million head, or 11.9 percent, from the cyclical peak of 31.64 million head in 2019. The beef cow herd is currently the smallest inventory since 1961. The projected 2025 calf crop is 33.1 million head after declining for seven consecutive years and is the smallest since 1941.

What began as modest cyclical herd liquidation in 2020, accelerated and extended from 2021 through 2024 as a result of widespread, roving drought that impacted most of the beef cattle production across the country. Lack of forage and adverse production conditions forced producers to reduce herds, significantly more than intended.

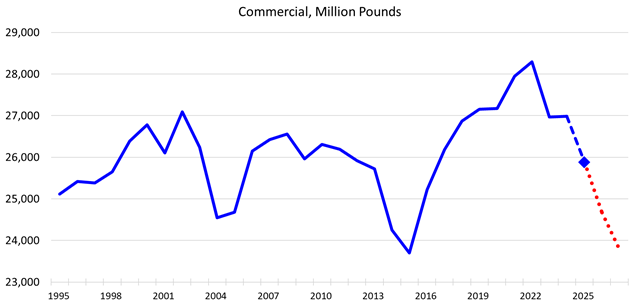

The beef cattle industry is complex and unique among livestock industries. Cattle are slow-growing animals that reproduce one at a time. One feature that is particularly important is that breeding cattle and cattle used for beef production originate from the same set of animals. This means that herd liquidation temporarily increases cattle slaughter and beef production. As the beef cow herd decreased after 2019, increased cow and heifer slaughter pushed beef production to record levels in 2022 (Figure 1, blue dashed line projection for 2025). Consumers – and politicians – enjoyed ample supplies of relatively inexpensive beef, oblivious to the fact that it meant that future beef production would inevitably decrease.

Beef production is now decreasing, pushing retail beef prices to record levels. Without herd rebuilding, beef production will remain low due to limited cattle numbers. Herd rebuilding is expected – at some point – which will lead to further reductions in beef production. The opposite of herd liquidation means that heifer retention for breeding will make a tight cattle supply even tighter as heifers currently used for beef production are retained for breeding and future beef production – leading to additional reductions in beef production in the meantime (Figure 1, red dotted line forecasts). There is no way (or any policy!) to change the fact that beef supplies will be tight – and get even tighter – over the next two to four years before beef production can be increased.

Figure 1. Beef Production

The current high cattle and beef prices developed over several years and at a high cost. Producers have been subjected to detrimental physical, emotional and financial tolls that affect operations for years. Cattle ranchers were forced to sell productive breeding animals prematurely, with most going to slaughter. Producers attempting to manage through the drought incurred increased production costs, including record high prices for hay – only to be finally forced to sell animals in many instances. Physical recovery of ranges/pastures and the financial recovery of ranches is a slow process. Producers are now enjoying high cattle prices and record returns per head, but low inventories mean that cattle ranches are selling fewer animals and still face high overhead costs to maintain pastures, fences, equipment and production facilities. High cattle prices for a period of time are necessary to allow cattle ranches to recover, rebuild, and prepare for the next cattle cycle.

That is the true source – and cost – of high cattle and beef prices.

Derrell Peel, OSU Extension livestock marketing specialist, breaks down how Argentinian beef imports could influence the U.S. cattle market and what it means for producers, consumers, and pricing trends. He also explains how the recent government shutdown is affecting access to key livestock data, making market analysis and decision-making more challenging on SunUpTV from October 25, 2025.

Fall Calving Cows and Creep Feed

Mark Z. Johnson, Oklahoma State University Extension Beef Cattle Breeding Specialist

Most of Oklahoma has received much needed rain over the past several days. This moisture will pay dividends for cool season grass pasture. However, based on the lack of optimum growing days remaining this fall, most of the benefit will likely be seen as we move into late winter and spring of 2026. For fall calving cow herds in Oklahoma, cool season grass pasture can offer nutritional supplementation to cows and high quality creep grazing opportunity for calves. If the cool season grass you were counting on for fall born calves is behind or non-existent as of now, consider creep feeding.

Ample research proves creep feeding will increase weaning weights with conversion efficiency ranging from 3 to 20 pounds of feed per pound of added weight gain. A summary of 31 experiments where calves had unlimited access to creep feed show the average increased calf weaning weight was 58 pounds. However, in commercial cow-calf operations, the value of added weight gain has not (historically), covered the added feed, labor and equipment needed. The exception would be when feed is exceptionally inexpensive and (or) when value of added weight gain is exceptionally high. As of now, feed is relatively inexpensive and the value of added weaning weight of calves (up to 600 pounds) is worth in excess $4/pound (historically high).

When grazing conditions are good, high-quality, abundant forage results in very poor creep feed conversion. Likewise, the greater the plane of maternal nutrition, the poorer the conversion of creep feed to calf gain. In OSU fall-calving experiments (and similar to the situation many of us find ourselves in at present), efficiency of creep feed conversion to calf gain is quite good because native range forage quality is low and cows are in a maintenance to negative energy balance (losing weight). Results have been around 4.5 to 5 pounds creep feed:gain when fall-calving cows are getting around 5 pounds of supplemental feed. However, the more supplement the cow is fed, the poorer the creep feed conversion. Situations that reduce calf nutrient availability (low milk production, low quality forage, overgrazed pastures and thus low forage availability, drought, fall-calving, etc.), improves the efficiency of creep feeding.

An ideal creep feed, designed for early stages of calf life, includes a balanced blend of neutral detergent fiber (NDF) and crude protein, allowing for both rumen development and lean tissue growth, plus additional energy (TDN) to help facilitate the growth. Crude protein concentrations should be between 14% and 16%, though protein requirements will vary depending on forage quality and calf performance goals. Rapidly growing, young calves have a high requirement for protein. Young calves have limited rumen capacity and won’t consume large quantities of feed, so nutrient density of the feed is key. Most commercial creep feeds are pelleted for palatability and ease of handling. If mixing your own ration: 1) keep the feed dust-free and well-mixed to prevent sorting, 2) when using liquid ingredients, make sure they do not clog the feeder and, 3) roll or coarsely crack grains (rather than finely grind) to reduce dust and potential for digestive upset. Likewise, including an ionophore at an efficacious dose will enhance feed efficiency.

Over-conditioned calves that are marketed at weaning can lead to discounts. The longer calves are exposed to unlimited creep consumption and the lower the forage quality, the more they want to eat. If calves are fed free choice creep for 90 days or longer, there is a risk of over-conditioning. A high quality, limit fed creep feed now, could be an effective bridge to the cool season grass you expect to see later.

Managing your cattle operation as a business enterprise should always be based economics. Evaluating the current cost of inputs versus the value those inputs create is the only logical way to accurately assess profit potential.

Reference

Creep Feeding Beef Calves: Profit or Expense? | UNL Beef | Nebraska

Dave Lalman, OSU Extension beef cattle specialist, discusses the pros and cons of creep feeding and has advice on how to determine whether this type of management will be cost-effective for your operation on SunUpTV from August 9, 2025.

Estimating Feed Intake in Beef Cows

David Lalman, Oklahoma State University Extension Beef Cattle Nutrition Specialist

An accurate estimate of feed intake is a critical element in determining a cow’s nutrient requirements at different stages of production. It is also necessary to establish appropriate stocking rate and carrying capacity for a given land base.

About a year ago, I shared our group’s work to evaluate and update estimates of feed intake for beef cows. One of the popular sources for feed intake estimates is a table published by Hibberd and Thrift in 1982. I provided the original table in the September 16, 2024 Cow Calf Corner Newsletter. In those guidelines, feed intake is expressed as a percentage of body weight and intake estimates are sensitive to diet quality, stage of production, and cow body weight. As mentioned in the previous article, the 43-year-old Hibberd and Thrift guidelines overestimated feed intake of gestating cows by about 3 pounds per day. However, the estimates for lactating cows were reasonably accurate.

We used the more recent dataset, along with Megan Gross’s validation work, to refine the original estimates. The updated guidelines presented in Table 1 more accurately represent expected feed intake in beef cows under standard production conditions.

It is important to understand that the guidelines assume the diet contains adequate protein to maintain optimal microbial growth, rumen fermentation, and passage rate. They also assume cows have unrestricted access to feed—whether that’s grazed forage, hay, or a total mixed ration—on a free-choice basis. If you are interested in more details, or if you need a more specific estimate of average daily feed intake, refer to our paper published in Translational Animal Science.

| Diet Quality | Diet TDN, % of Dry Matter | Dry, Gestating Dry matter intake, % of body weight |

Lactating Dry matter intake, % of body weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | < 53 | 1.8 | 2.1 |

| Moderate | 53 to 57 | 2.1 | 2.5 |

| High-Moderate | 58 to 63 | 2.4 | 2.8 |

| High | >63 | 2.5 | 2.9 |

Adapted from Hibberd and Thrift, 1982 and Gross et al., 2024

Reference

Megan A Gross, Amanda L Holder, Alexi N Moehlenpah, Harvey C Freetly, Carla L Goad, Paul A Beck, Eric A DeVuyst, David L Lalman, Predicting feed intake in confined beef cows, Translational Animal Science, Volume 8, 2024.

Dave Lalman, OSU Extension beef cattle specialist takes a deep dive feed costs of raising a cow - the biggest factor that can make or break profitability in a cow-calf operation. Dr. Lalman explains how feed efficiency, forage quality, and management practices directly impact production economics and ranch profitability on SunUpTV from October 20, 2025.

Emerging Bovine Disease Update: New World Screwworm

Rosslyn Biggs, DVM, Oklahoma State University Extension Beef Cattle Specialist

The threat of New World Screwworm (NWS), Cochliomyia hominivorax, continues to impact cattle producers in Mexico. Although eradicated from the continental U.S., this parasitic fly still poses serious risks to livestock, wildlife, pets, and humans as its infestation front advances northward.

In August 2025, U.S. public health authorities confirmed a human case of NWS in the United States in a patient returning from El Salvador. This case appears to be isolated case with no further human or animal spread detected domestically. In September 2025, Mexico confirmed a detection of NWS less than 70 miles from the U.S. border. The infected animal was an 8-month-old calf in a herd moved from southern Mexico. The USDA continues to work closely with Mexican authorities supporting sterile fly release across Mexico.

Although risk to livestock and wildlife remains low, surveillance measures have been elevated across the southern border in Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico. Thousands of traps have been dispersed with over 13,000 surveillance samples testing negative for NWS.

Treatment options have also been evaluated with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration conditionally approving Dectomax-CA1 (doramectin) injectable solution for the prevention and treatment of NWS larval infestations, and prevention of NWS reinfestation for 21 days in cattle only. To reduce the risk of parasite resistance development, producers and veterinarians have been encouraged to use antiparasitic drugs like Dectomax-CA1 only when medically necessary, in accordance with the product labeling, and as part of a strategic parasite management.

Producers and veterinarians are encouraged to remain vigilant by:

- Examining animals daily, especially after any handling or procedures.

- Cultivating a solid veterinary relationship and maintain a response plan for suspected cases.

- Observing biosecurity and minimizing unnecessary animal movement or exposure.

- Watching for disease notices in your region.

- Reporting any clinical signs consistent with NWS (lesions, maggots, odor, extreme irritation) to your veterinarian or State Veterinarian.

This column reflects the latest information available as of October 15, 2025. These are evolving situations. Animal owners are encouraged to stay informed and watch for updates as new information becomes available.

A link to resources with current New World Screwworm information.