Cow-Calf Corner | March 24, 2025

A Cattle Industry Update from Northern Mexico

Derrell S. Peel, Oklahoma State University Extension Livestock Marketing Specialist

An invitation to speak at the annual meeting of the Unión Ganadera Regional De Chihuahua in Chihuahua, Mexico last week provided me an opportunity to get an update on the tough conditions facing beef cattle producers in northern Mexico. The industry there is facing multiple threats simultaneously that has cattle producers on the defense and struggling to survive.

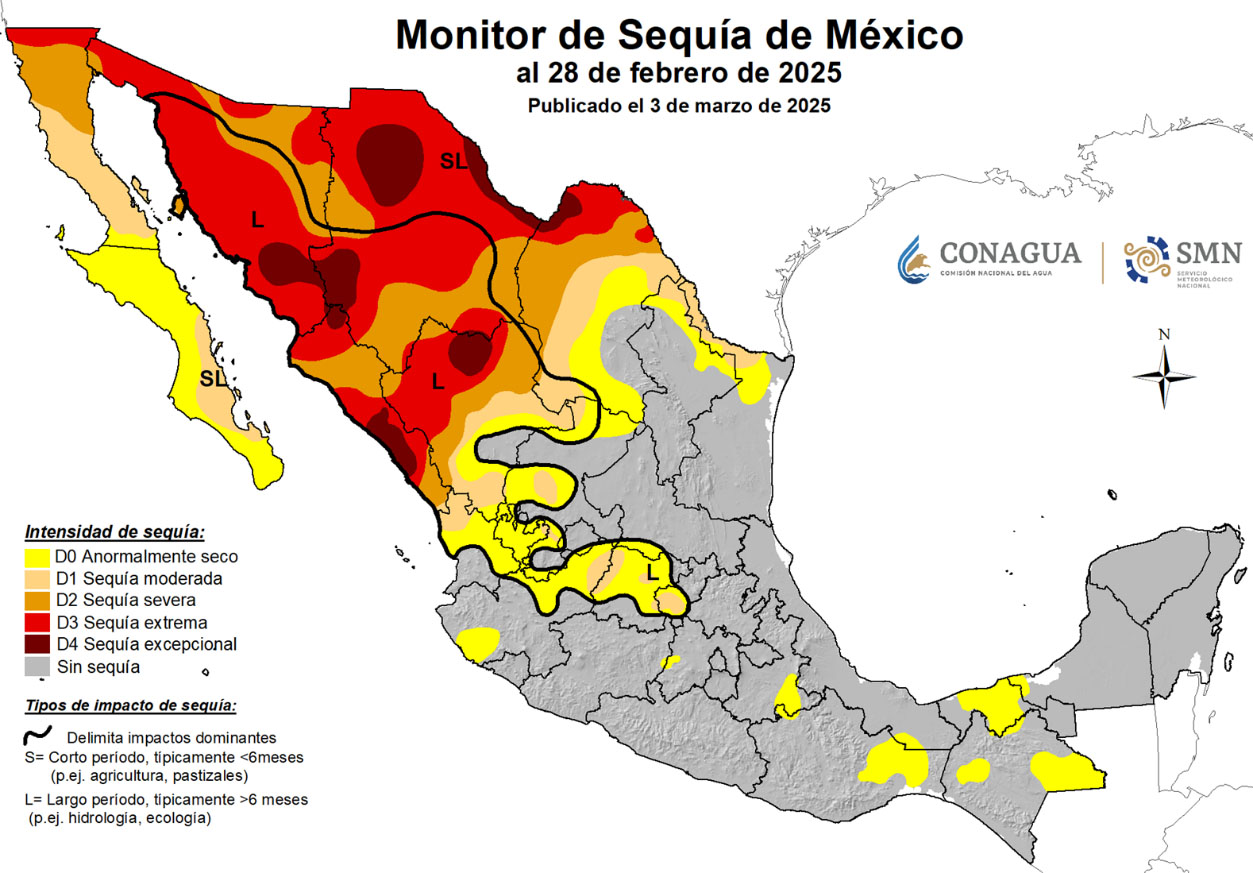

Drought has been the major issue in northern Mexico the past two years. Chihuahua receives just a little over 16 inches of rain per year on average but has received a total of only 19.2 inches in the last 28 months, since the end of the rainy season in 2022. The result is the critical drought situation shown in Figure 1. Drought has forced producers to liquidate cows and reduce the herd in the region. Pastures are bare and feed is in short supply. Some cows have been relocated to central Mexico, where conditions improved in 2024 after a drought in 2023. Cattle producers are trying to hold onto remaining animals for now, hoping that a normal rainy season will arrive in June.

Figure 1.

Adding significantly to the challenges of Mexican producers is the discovery of New World Screwworm in southern Mexico and the closure of the U.S. border to livestock from late November through early February. November and December typically account for over 22 percent of annual Mexican cattle shipments to the U.S., along with another 7.2 percent in January; but much of that was preempted by the border closure. The drought and feed scarcity has made it very difficult and expensive to hold cattle waiting for access to the U.S. market. Some cattle have been rerouted into domestic Mexican markets.

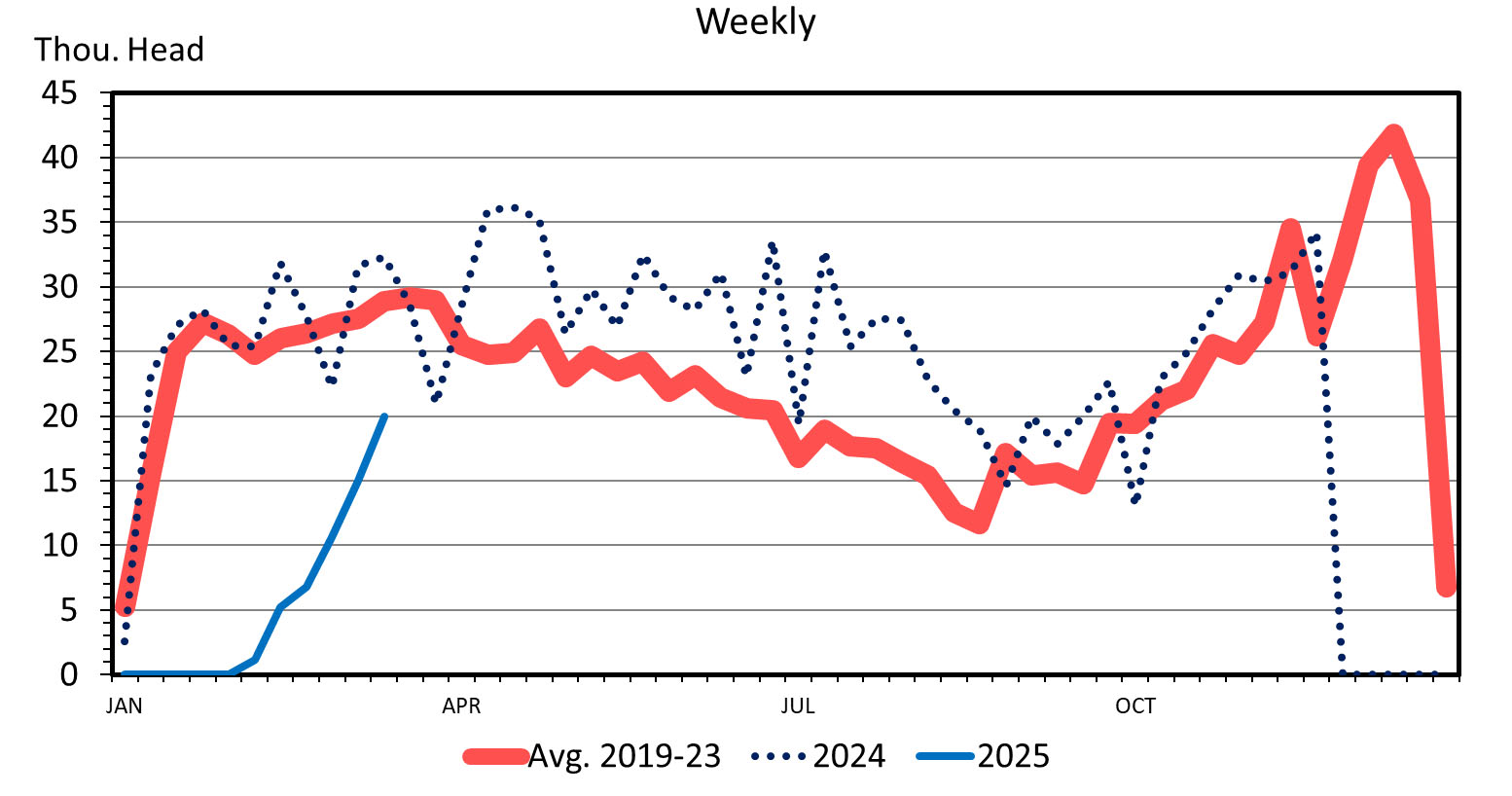

The border reopened in early February with restricted volumes and is slowly recovering normal weekly cattle flows into the U.S. (Figure 2). In 2024, 37.7 percent of Mexican cattle imports into the U.S. were spayed heifers, much higher than the average of 15.7 percent in the previous 20 years. The sharp increase in heifer exports is likely further indication of drought-forced liquidation of herds in northern Mexico. Since the border reopened in February, 42.2 percent of Mexican cattle imported into the U.S. have been spayed heifers. This is due, in part, to the additional challenge that heifers must be exported within 180 days after spaying. This means that any heifers spayed up until the border closure on November 22, 2024, must cross the border by May 21, 2025.

Figure 2. Feeder Cattle Imports from Mexico

Some heifers spayed earlier last fall have reached the six-month limit and have been marketed in the domestic Mexican market, at sharply lower values due to the sudden supply surge in Mexico. Heifers have a maximum 159-day window for export as they must wait a minimum of 21 days after spay surgery but be exported by 180 days after surgery. Heifers must be fully healed from the surgery and realistically this means waiting at least a month before exporting. With the uncertainty of border access until recently, it is likely that few heifers were spayed since November, so heifer exports are expected to drop in the coming months, at least for a while. Total Mexican cattle exports to the U.S. are expected to be significantly lower year over year in 2025 due to the slow start to exports in the first quarter of the year, fewer heifers in the export mix, and the likelihood that total cattle numbers are down, meaning that there are simply less Mexican cattle available for export.

The final challenge for Mexican cattle producers is the looming U.S. tariffs on Mexican products. Many questions remain about if, when, and by how much trade will be restricted going forward. The additional uncertainty adds to the stress and challenges of Mexican producers in this very difficult time.

Derrell Peel, OSU Extension livestock marketing specialist, discusses the increasing drought and how it could impact heifer retention this spring on SunUpTV from March 22, 2025.

Best Management Practices of Replacement Heifers

Mark Z. Johnson, Oklahoma State University Extension Beef Cattle Breeding Specialist

In order to maximize profit potential it is important to have heifers calving at two years of age. Research shows heifers becoming pregnant early in their first breeding season, (specifically the first 21 days) remain in the herd longer and produce more total calf weaning weight over their lifetime in production.

How do we select and manage replacement heifers so that they are having fertile heats and ready to conceive by 14-15 months of age? Genetics, photoperiod, level of nutrition and growth rate all influence when beef heifers reach puberty; that being said, heifers that have reached 65% of their mature weight by this age should have reached puberty and be ready to breed. Obviously, age should be taken into account, (along with other selection criterion), when selecting replacements, with older heifers having an advantage. Heifers calves born earlier in the calving season, are produced by cows that conceived earlier in the breeding season.

After heifers are selected, how do we arrive at the target weight they need to gain from weaning until their first breeding season? First we need an accurate estimate of the average mature cow weight. By using the weights taken at weaning time on the 4 to 7-year old cows and adjusting to a Body Condition Score of 5 (Chapter 20 Beef Cattle Manual) we can calculate average mature weight of the cowherd.

What is the best way to feed to reach that Target Weight? In a normal Oklahoma year, spring born heifers weaned in fall are old enough to make good use of wheat pasture typically available by late November and gain 1.5 lb. per day (or better) to reach targeted weight. With wheat pasture conditions sporadic this year in Oklahoma, it is comforting to know that heifers can be grown very slowly through the winter months and fed harder for the couple of months going into breeding season in order to reach target weight by breeding season. This is the development method referred to as SLOW-FAST in Chapter 29 of the newest edition of the OSU Beef Cattle Manual. The SLOW-FAST feeding method for replacement heifers can also be a more cost effective means of reaching the target weight than feeding for a consistent daily gain over the entire feeding period.

References

Beef Cattle Manual. Eight Edition. E-913. Oklahoma Cooperative Extension. Chapters 20 and 29.

Mark Johnson, OSU Extension beef cattle breeding specialist, discusses bull preparation for breeding season on Cow-Calf Corner segment of SunUpTV.

Hay Season Will Soon Be Upon Us

Scott Clawson, OSU Cooperative Extension NE Area Extension Agriculture Economist

The value of a hay bale is determined by a complex set of supply and demand factors. We can summarize this by saying that hay, especially in drought conditions, acts an essential item for the cowherd. Thus, it will be purchased for the cows regardless of price until it reaches a point where liquidation of cows becomes necessary. While western Oklahoma is parched, most two-lane highways in eastern Oklahoma have hay for sale and fertilizer spreaders are starting to shake off the cobwebs.

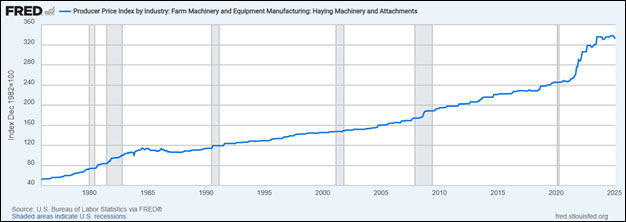

The market determines what the value of the hay is. This issue is separate from what it costs to produce hay. It seems like no conversation about the cattle business can occur without comparisons to 2014. From December 2014 to January 2025, fertilizers, chemicals (including herbicides), and fuel have increased by 13%, 15%, and 9%, respectively1. During the same period, supply/repair costs and machinery costs have risen by 38% and 51%, respectively1. Admittedly, this comparison is not bulletproof. It compares two points in time and the categories are broad, but it suggests that the cost of owning and maintaining equipment warrants further analysis on the ranch. The graph illustrates the price trend of haying machinery and attachments. Careful consideration and planning will be needed when replacing these assets.

So, now what? Are there other strategies to consider? Currently, there is a decent chance that hay could be purchased at a lower price than the cost of production (assuming all costs are considered). A ranch that has adequate hay storage could explore scaling back hay production this year and buying hay on the open market. This would create the opportunity to reduce equipment wear and tear, extend its lifespan, increase grazable acres, and potentially lower fertility inputs. Having adequate hay storage capacity provides multiple risk management and business opportunities. Building or expanding that capacity could serve as a worthwhile investment as cattle prices allow money to be reinvested.

Running cows and row crop farming don’t always overlap, but in this matter, they do. The price of our crops (hay, corn, etc.) is sensitive to changes in supply. Sufficient hay inventory and expected production will continue to pressure hay prices. As cattle prices continue to flex their muscles, how we allocate these profits will have long-term implications for the ranch.

1Agriculture Prices (February 2025). USDA, National Agriculture Statistics Service