Cow-Calf Corner | January 6, 2025

Cattle Markets 2025: To Retain or Not to Retain

Derrell S. Peel, Oklahoma State University Extension Livestock Marketing Specialist

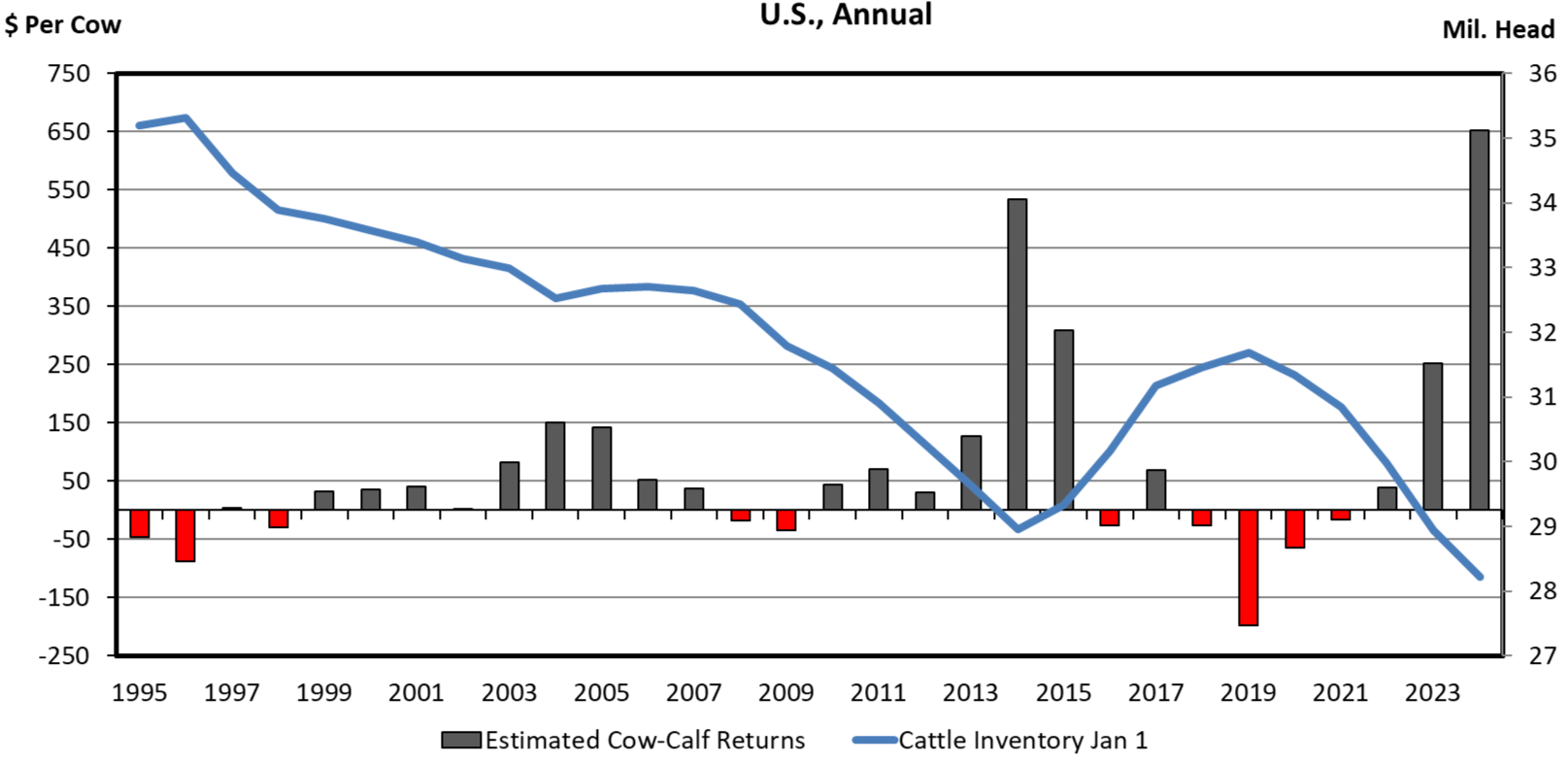

Average Oklahoma steer calf prices increased over 61 percent from 2022 to 2024, leading to a sharp increase in average cow-calf returns (Figure 1). Cow-calf returns vary significantly across producers due to widely variable costs of production, but the message is clear – increasingly strong market signals for cow-calf producers to expand the beef cow herd. Positive cow-calf returns typically result, with a delay, in herd expansion. Figure 1 shows the strong cow herd inventory response to positive returns a decade ago.

Figure 1. Cow-Calf Returns And Beef Cow Inventory

New inventory data at the end of the month will confirm current herd status but it is likely that the herd continued to decrease in 2024 and prospects for herd growth in 2025 are limited.

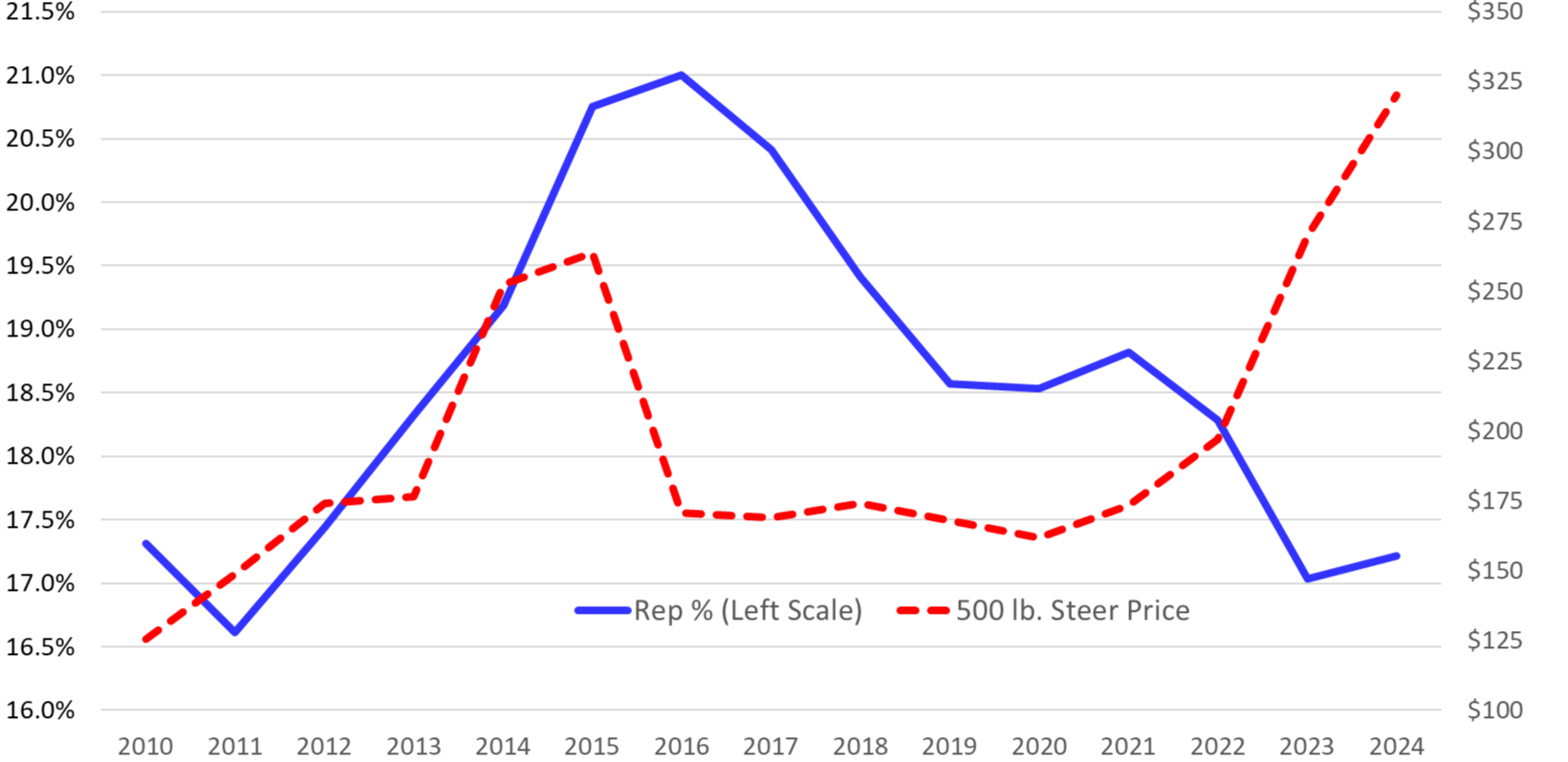

Figure 2. Beef Replacement Heifers as % of Beef Cow Inventory 500lb Steer Price, Southern Plains,

$/cwt.

Figure 2 shows a sharp contrast to higher cattle prices leading to the herd rebuild in 2014-2019 compared to the current situation. Heifer retention began in 2012, setting the stage for herd expansion that began in 2014. Increased heifer retention simultaneous with increasing cattle prices squeezed feeder supplies leading to the (then) record feeder prices in 2014 – 2015. Contrast that with the right side of Figure 2 where replacement heifer inventories have shown no significant increase thus far, despite rising feeder cattle prices. Heifer slaughter data through the end of the year, along with heifer on-feed inventories and feeder cattle sales receipts data all suggest little, if any heifer retention in 2024.

Not only did the beef cow herd likely get smaller in 2024, but the limited supplies of replacement heifers also suggests that the beef cow herd may get smaller yet in 2025 or, at best, stabilize at very low inventories. Historically, herd expansions require a year or two to gain momentum before herd inventories begin to increase. That process has not begun at this time.

If heifer retention begins in 2025, several outcomes are expected; tighter feeder supplies will push cattle prices and cow-calf returns higher; retained heifer calves will lead to increased replacement heifer inventories in 2026 and potential herd growth beginning in 2027. Depending on the pace of heifer retention, herd expansion could lead to cyclical production increases and price peaks in the second half of the decade.

If heifer retention does not begin in 2025, the cow herd will continue to dwindle, and cattle supplies will continue to slowly contract with higher cattle prices and a smaller industry until herd rebuilding begins. Either way, cattle prices are expected to remain elevated for at least two to four more years.

When to Assist with the Calving Process – the Three Stages of Parturition

Mark Z. Johnson, Oklahoma State University Extension Beef Cattle Breeding Specialist

Parturition, or the birthing process, has three stages. Understanding the stages is critical in order to know when/if we need to provide assistance during calving season to increase the likelihood a live calf is born alive and off to a good start.

Stage 1

Dilation of the Cervix. The may take hours or days to complete and can easily go unnoticed. Uterine muscular activity is quiet during this stage as the cervix softens and the pelvic ligaments relax. During this stage, you may notice switching of the tail and a thick clear mucus string hanging from the vagina. Cow’s appetite may decrease and they may separate themselves off from the herd. Increased uterine contractions at the end of this stage push uterine contents against the cervix causing further dilation.

Stage 2

Delivery of the Calf. This stage officially begins with the appearance of the water bag at the vulva. This is the time to start your clock. Research has shown that healthy heifers with normal calf presentation will calve unassisted within one hour of the onset of stage two. Healthy cows with normal calf presentation will calve within 22 minutes of the start of stage two. This suggests that normal stage two of parturition should be defined as approximately 60 minutes for heifers and 30 minutes for adult cows. In heifers, not only is the pelvic opening smaller, but the soft tissue has never been expanded prior to that first birth. Older cows have had deliveries before and birth often proceeds quite rapidly unless there is some abnormality such as a very large calf, backwards calf or twin birth.

When Should We Assist? Offering assistance is a matter of judgment and good judgment is the result of experience. If you have a cow or heifer laboring and don’t know when stage two began you will need to do a vaginal exam. If possible, have the cow up on her feet, restrained in a well-lit area that is safe for both you and the cow. It is much easier when both you and the cow are standing. Start by cleaning the cow’s vulva, rectum and surrounding area, as well as your hands and arms with soap and water. Cleanliness is important. Wear protective sleeves. Gentleness and lubrication are important. Feel for the cervix, if not dilated it will feel as if your hand passes through or along a firm, tubular or circular structure. Once fully dilated, you should no longer feel the cervical ridge. Can you feel the calf? A normal anterior presentation will permit you to feel the calf’s feet and nose with the spine of the calf resting just under the cow’s spine. If the presentation is normal and the water bag is still intact around the calf, you can allow up to an hour to permit the cow to calf unassisted. If the water bag has broken and the cervix is fully dilated, the calf needs to be delivered sooner. If you detect an abnormal presentation, encounter something that doesn’t feel right or a situation you can’t manage, you will need to contact a veterinarian for assistance.

Stage 3

Delivery of the Placenta. The placenta should be shed within 8 – 12 hours after delivery of the calf. If retained, do not forcibly remove it. Administering antibiotics may be necessary if the cow acts sick. The placenta will slough out in 4 – 7 days.

Mark Johnson, OSU Extension beef cattle breeding specialist, explains when it’s time to assist during calving on SunUpTV from February 17, 2024.

Reference

The 3 Stages of Bovine Parturition. University of Wisconsin-Madison Extension

Managing Cattle Through Winter Weather

Paul Beck, Oklahoma State University Extension Beef Cattle Nutrition Specialist

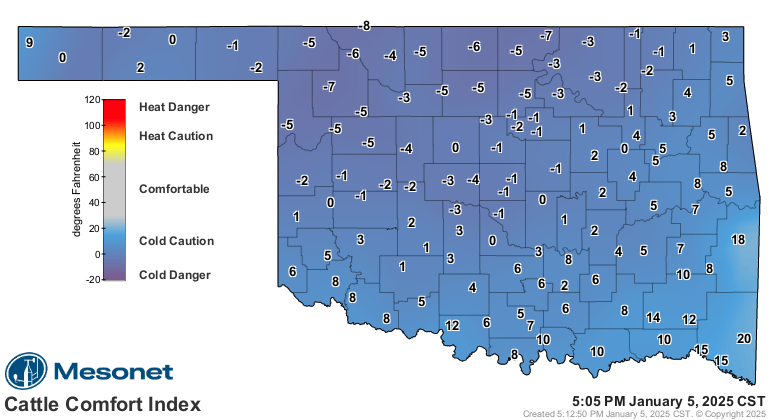

Up until now we have had some fairly temperate weather this winter. This week the cold front has moved in, putting us in the “Cold Caution” category on the Mesonet Cattle Comfort Index .

Cows lose their acclimation to cold when we have a periods of nice weather, increasing the impact of cold temperatures. The cow’s fleshiness and hair coat have a big impact on their tolerance to colder conditions. Cows in good body condition, having body condition scores of 5 to 6, with good thick winter hair coats have a “lower critical temperature” of around 32° Fahrenheit. Thin cows with sparse hair coat are at more risk with lower critical temperatures of around 40° F, while cows with wet haircoat have lower critical temperature of 59° F. For each degree below the lower critical temperature energy requirements increase by 1%. When we have wind chills that get to 0° F, maintenance energy requirements will increase by up to 30 to 40%.

Here are some things to consider for this week’s winter weather:

- Make sure cattle have access to as much hay as they want to eat.

- Ruminal fermentation helps keep the animals warm.

- If increasing supplementation rates to help offset energy deficiencies it is best to feed supplements every day.

- Feed cattle beside or in a grove of trees or some other windbreak that is large enough

for all the animals to gather. The better the windbreak, the lower the animal’s cold

stress.

- If there is no natural or constructed windbreak available near a water source, a quick and simple one can be made by placing a line of round bales of straw or low-quality hay where cattle can bed down.

- Ensure cattle have unrestricted access to unfrozen water. If water intake is limited,

hay intake is reduced and ruminal fermentation is affected.

- Feed cattle relatively close to their water source. The farther away the water source, the longer they will wait to get a drink.

- Unrolling low-quality hay as bedding will help provide relief from the extreme temperatures.

Dr. Mark Johnson, OSU Extension beef cattle breeding specialist, discusses cattle management in the winter from SunUpTV on January 20, 2024.