Cow-Calf Corner | February 24, 2025

A Review of Feedlot Structure and 2024 Marketings

Derrell S. Peel, Oklahoma State University Extension Livestock Marketing Specialist

The latest USDA-NASS Cattle on Feed report pegged the February 1 feedlot inventory at 11.716 million head in feedlots with 1,000+ capacity, down 0.7 percent year over year. January marketings were 101.4 percent of one year ago and placements were 101.7 percent of last year. The report was well anticipated with values close to pre-report estimates.

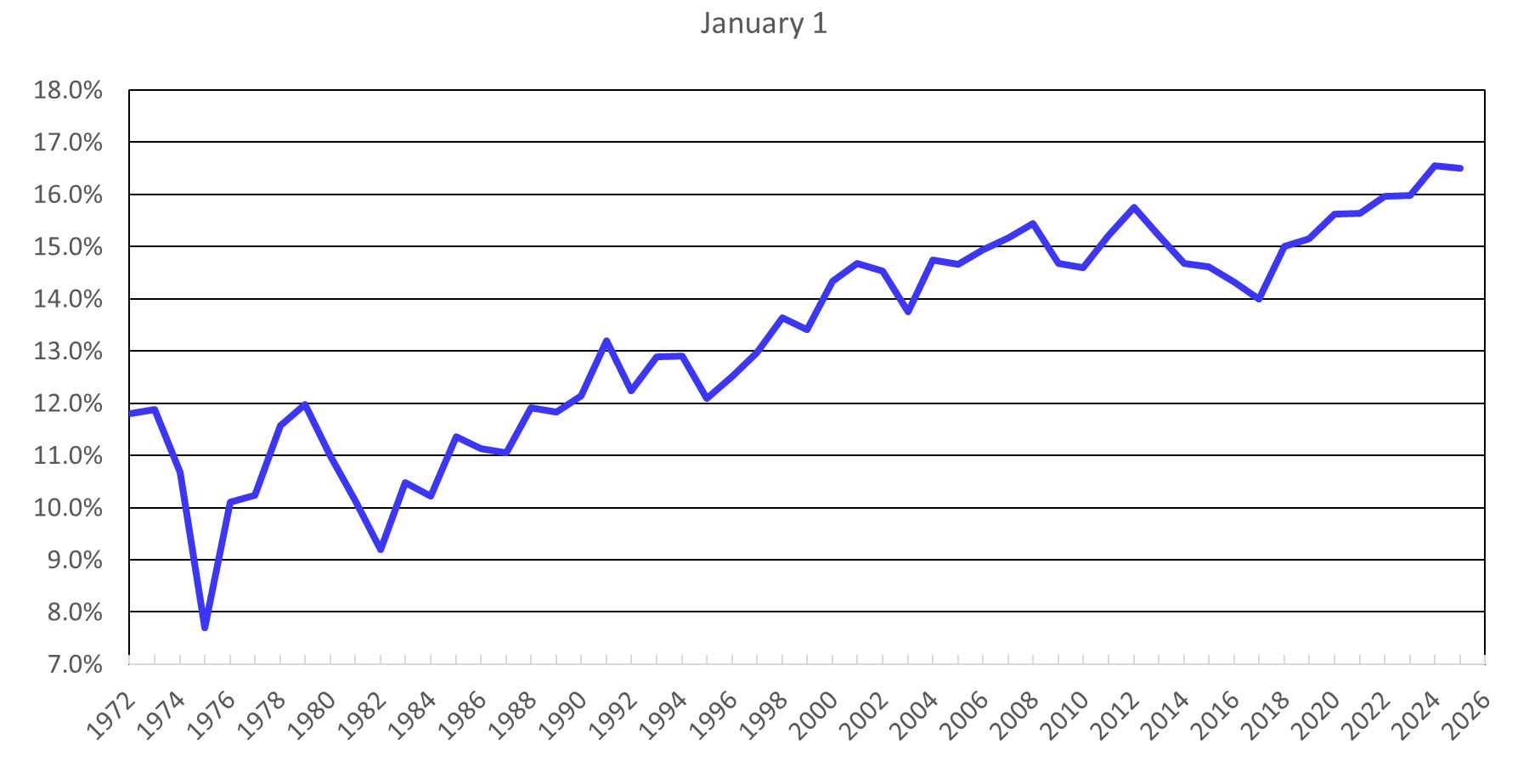

The February report also contained a summary of 2024 feedlot production and the structure of the feedlot industry coming into 2025. The total U.S. feedlot inventory on January 1, 2025 was 14.297 million head, including 2.474 million head in feedlots with capacity less than 1,000 head (Table 1). Since cattle inventories peaked in the mid-1970s, feedlot inventories have represented a growing percentage of cattle inventories (Figure 1). Feedlot inventories represented 16.5 percent of total cattle inventories on January 1, 2025, down fractionally from the peak of 16.6 percent last year.

Figure 1. Cattle on Feed Inventory as % of All Cattle and Calves

Table 1 shows the size distribution of feedlots and their contribution to total feedlot production. A total of 2105 feedlots with capacity of 1,000+ head (included in monthly Cattle on Feed reports) accounted for 82.7 percent of the January 1 feedlot inventory and 87.2 percent of total feedlot production in 2024. A total of 24,000 feedlots with less than 1,000 head capacity accounted for 17.3 percent of feedlot inventory on January 1 and 12.8 percent of total feedlot marketings in 2024. Feedlots with capacity over 50,000 head made up 3.8 percent of feedlots over 1,000 head capacity but accounted for 34.8 percent of inventory and 35.1 percent marketings last year. Over 50 percent of feedlot inventories on January 1 and annual marketings in 2024 were in feedlots over 32,000 head of capacity, 6.9 percent of feedlots with 1000+ head.

| Feedlot Capacity | Feedlots | % of Feedlots >1000 Hd. | Inventory Jan. 1, 2025 | % of Total Inventory | Marketings 2024 | % of Total Marketings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head | Number | 1,000 Head | 1,000 Head | |||

| <1,000 | 24,000 | 2,473.7 | 17.3 | 3,180.0 | 12.8 | |

| 1,000 – 1,999 | 740 | 35.5 | 363.0 | 2.5 | 610.0 | 2.5 |

| 2,000 – 3,999 | 530 | 25.2 | 630.0 | 4.4 | 1,220.0 | 4.9 |

| 4,000 – 7,999 | 370 | 27.6 | 930.0 | 6.5 | 1,790.0 | 7.2 |

| 8,000 – 15,999 | 190 | 9.0 | 1,040.0 | 7.3 | 1,990.0 | 8.0 |

| 16,000 – 23,999 | 85 | 4.0 | 940.0 | 6.6 | 1,840.0 | 7.4 |

| 24,000 – 31,999 | 45 | 2.1 | 760.0 | 5.3 | 1,550.0 | 6.2 |

| 32,000 – 49,999 | 65 | 3.1 | 2,190.0 | 15.3 | 3,720.0 | 15.8 |

| >50,000 | 80 | 3.8 | 4,970.0 | 34.8 | 8,720.0 | 35.1 |

| Subtotal >1,000 | 2,105 | 11,823.0 | 82.7 | 21,640.0 | 87.2 | |

| Total | 26,105 | 14,296.7 | 24,820.0 |

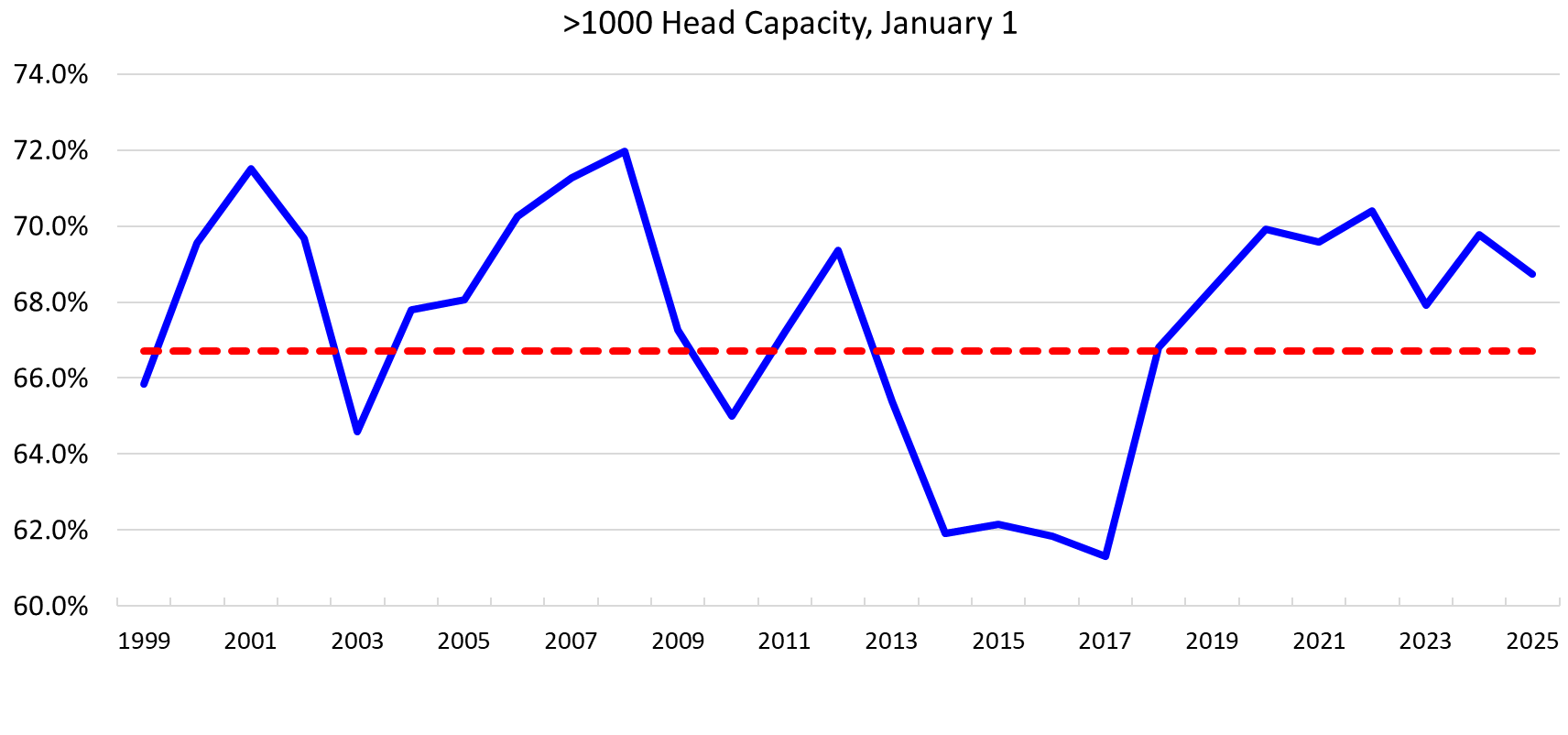

The estimated total feedlot capacity (1,000+ head) on January 1, 2025 was 17.2 million head, up fractionally from the previous year. Total feedlot capacity has not changed significantly in recent years and has averaged 17.13 million head since 2011. Figure 2 shows the January 1 feedlot inventory as a percentage of feedlot capacity.

Figure 2. Cattle on Feed as % of Feedlot Capacity

The cattle on feed percentage of feedlot capacity on January 1, 2025 was 68.7 percent, down from 69.8 percent in 2024 and from the recent peak of 70.4 percent in 2022. For the past fifteen years, feedlot inventories have averaged 66.7 percent of the feedlot capacity (red dotted line). The percentage dropped significantly from 2014-2017 during herd expansion. Ever tighter feeder cattle supplies and the prospect of heifer retention for herd rebuilding mean that the percentage is likely to decrease in the future.

Temperature Variation and Baby Calf Health

Mark Z. Johnson, Oklahoma State University Extension Beef Cattle Breeding Specialist

After the extremely cold temperatures across Oklahoma over the past couple of weeks when many are in the middle of calving season, our near-term forecasts now call for daytime highs of 70 degrees F (or higher). It is important to remember that the calves born in single digit temperatures need to be monitored closely as the weather becomes dramatically warmer. A calf’s health is significantly impacted by ambient temperature. The most comfortable range for young calves being between 55 and 70 degrees F. This range is considered the thermoneutral zone for young calves where a calf can maintain its body temperature without expending extra energy. Heat or cold stress results in direct economic losses because of increased calf mortality and morbidity, as well as indirect costs caused by reduced weight gain, performance, and long-term survival.

Thermic stress in calves is observed not only with extremely high or low temperatures, but also extreme temperature variations. Variables such as relative humidity and wind speed can also contribute to thermic stress. Heat stress is actually harder on young calves than cold stress. When calves are heat stressed they lose appetite, eat less and are quicker to become dehydrated. Thermoregulation in calves is similar to that of adult cattle, but new born calves have an immature “thermostat” and accordingly have more problems regulating body temperature during weather extremes. Thermoregulation is the ability of homeothermic animals to keep their body temperature within a certain range despite being exposed to different ambient temperatures. A physiological core temperature is maintained by generating metabolic heat as well as exchanging heat with the environment. Cattle are able to adjust to adverse climate by means of acclimatization and adaptation. Extreme climatic conditions that cannot be compensated by thermoregulatory mechanisms result in thermic stress.

As the weather becomes more pleasant and day time highs approach 70 degrees F, keep an eye on your young calves soaking up the sun. The signs of overheating may not be as dramatic as the signs of cold stress but can be just as damaging to a calf’s health.

Legumes in Grass Based Grazing Systems

Mike Trammel, OSU Cooperative Extension SE Area Agronomy Specialist

There are several important benefits associated with establishing other forage crops into existing sods. Over the years, research and on-farm experience have shown that the addition of legumes to grass based grazing systems can result in a number of potential improvements such as diversity, stand productivity, improved forage quality and extended grazing season. Legumes and grasses have unique herbage and root morphology traits that allow for a greater combined use of environmental resources such as light, moisture and minerals. One of the more compelling reasons to use pasture mixtures containing both legumes and grasses is nitrogen (N) fixation.

Nitrogen is required for high levels of forage production and N deficiency is a common limitation to forage/livestock production. The atmosphere consists of about 80 percent N. However, the N in the atmosphere is in the form of an inert gas that is unavailable to plants. Nature provides some N production from sources such as soil bacteria, blue-green algae, and atmospheric lightning. Most commercially available N is synthetically made using the Haber-Bosch process which combines atmospheric N with hydrogen gas under high pressure and temperature to produce ammonium nitrate and urea. Legume plants also have the ability to produce substantial quantities of low-cost N.

Most legumes have a symbiotic or mutually beneficial relationship with Rhizobium type bacteria. The bacteria infect the roots of legumes from which they obtain food, and the bacteria obtain N from the soil air and fix it into a form usable by plants. This fixed N is accumulated in small appendages called nodules that form on the roots of the legume plant. This allows them to provide enough N for their own growth as well as some or all of the N needed for associated plants growing in the same field. Most fixed N is found in leaves and stems. In a pasture, this fixed N is primarily available as protein and is consumed by grazing livestock. Much of the N consumed as forage is recycled through urine and manure. As roots, stems, and leaves decay over time, N is released for use by other plants. In numerous studies, the amount of N produced per acre by a good stand of alfalfa or clover ranges from 50 to 200 pounds per acre (Table 1). With N at $0.60 pound (urea at $555 per ton) this would be equivalent to $30 to $120 per acre.

| Species | Seed cost/lb | Seeding rate/acre | Seed costs/acre | Potential N fixed/year (lb/acre) | Value* of N fixed @ 0.60 lb/of N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alfalfa | $3.50-$4.50 | 20 | $70-$90 | 150-200 | $90-$120 |

| White Clover | $3.00-$7.50 | 2 | $6-$15 | 75-150 | $45-$90 |

| Red Clover | $2.50-$4.00 | 8 | $20-$32 | 75-200 | $45-$120 |

| Crimson Clover | $0.75-$1.50 | 20 | $15-$30 | 50-150 | $30-$90 |

The range of N fixation potential for the legume species listed in Table 1 is wide and partially related to the percentage of legumes growing in the grass stand. The lower end of the range in Table 1 would represent the amount of N fixed when about 30% of the stand consists of legumes, whereas the upper end would reflect pure stands of legumes under ideal growing conditions. Legume plants should be well distributed across the pasture to see a more uniform response and it is recommended that legumes make up at least 30% of the pasture for no additional N to be applied to the system. Over time, consistent use of legumes in grass pastures will help build soil quality, increase plant diversity, boost productivity, improve forage quality and help extend the grazing system.

New World Screwworm in Mexico

Rosslyn Biggs, DVM, OSU College of Veterinary Medicine, Extension Beef Cattle Specialist

Cattle producers face an ever-evolving list of challenges in maintaining the health and safety of their herds. Now, a threat has reemerged in Mexico that could impact the livelihood of many ranchers—New World Screwworm (NWS). This parasitic fly is known for infesting open wounds on livestock, especially cattle. NWS also poses a significant threat to other mammals, including humans, and occasionally, birds.

In November 2024, reports confirmed that the pest had resurfaced in the southern Mexico state of Chiapas. Prior to this time NWS had effectively been eradicated from the continental United States (US) since the 1970s with partnerships between the US and Mexico pushing the pest to Mexico’s southern border by 1986. Although due to the pest’s ability to be unknowingly transported there have been isolated incidents of NWS in the US such as the 2016 identification in the Florida Keys in Key deer, pets, and swine.

NWS, Cochliomyia hominivorax, is a parasitic fly native to parts of Central and South America. Its larvae infest open wounds on mammals and feed on live tissue, unlike other maggots that feed on dead tissue. Infected animals experience significant pain, swelling, foul odor, and infection. If left untreated, the infestation can lead to severe tissue damage and even death within two weeks.

A female fly typically lays eggs near open wounds, mucous membranes, or body orifices. In cattle, the primary risk of screwworm infestation comes from exposed tissue such as areas created during branding, tagging, dehorning, or castration. Even minor cuts and the umbilicus of newborns are vulnerable.

The NWS female fly only mates once in its lifetime. With this understanding, the sterile insect technique has been utilized for eradication of the pest. The US and Panama operate the sterile male fly production facility in Panama through the US Commission for Eradication and Prevention of Screwworm. This facility has historically produced 100 million sterile flies per week. Male flies are irradiated at the facility and then released to mate with wild females. Over time, along with stringent treatment of infected animals and movement restrictions, the fly was maintained at the biological barrier in Panama. Multiple factors played a role in the reemergence of the pest into Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, Belize and now Mexico.

To protect the US, ruminant movement from Mexico was halted after the identification of NWS in the country. In February 2025, the USDA announced a protocol to resume imports. The comprehensive protocol involves significant inspection and treatment procedures. Additionally, the USDA is working to release sterile flies at strategic locations in Mexico and Central America.

NWS is a state and federally reportable Foreign Animal Disease in the US. If producers suspect NWS, they should contact their veterinarian and animal health authorities for instructions on how to submit samples for confirmation.

The resurgence of the New World Screwworm is a real threat to the cattle industry. By taking proactive steps to protect livestock, cattlemen and animal health officials can help prevent the spread of this destructive pest.