Cow-Calf Corner | December 15, 2025

High Beef Prices: If You want to Help…Stop Trying to Help

Derrell S. Peel, Oklahoma State University Extension Livestock Marketing Specialist

Beef prices have become, unfortunately, the federal poster child for high food prices and concerns about consumer affordability. Much political attention is focused on high beef prices as part of broader inflationary concerns among numerous food items - resulting from tariffs and other macroeconomic factors. Ironically, high beef prices are only coincidentally contributing to inflation concerns in that beef prices are high because of internal beef market fundamentals rather than systemic inflation factors. Strong beef supply and demand fundamentals mean that beef prices would be high even if there were no other inflation or macroeconomic concerns.

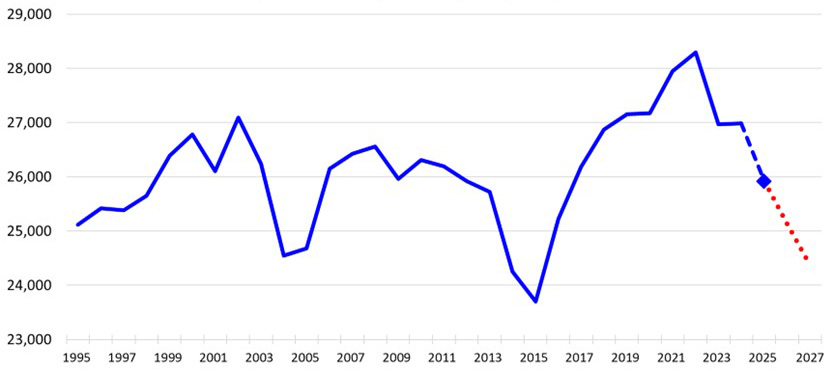

Beef production is down year over year in 2025 and expected to decrease further in the next two years (Figure1). Decreased beef production is the result of smaller U.S. calf crops for seven consecutive years since 2018. The feeder cattle supply continues to tighten as a result, leading to lower feedlot production, decreased cattle slaughter and lower beef production. The beef cow herd may stabilize temporarily into 2026 as a result of decreased beef cow culling in the last three years. However, there is currently no indication of significant heifer retention, and it will not be possible to hold the herd inventory stable, and certainly not to rebuild inventories, without additional heifer retention. Therefore, beef production is expected continue decreasing for the next couple years…likely leading to even higher beef prices.

Figure 1. Beef Production Commercial, Million Pounds, 2025 Projected, 2026/2027 Forecast

No matter how much they would like to lower beef prices, there is essentially nothing that politicians can do to change the beef market reality. Beef imports are not the answer. The market is already responding to tight supply conditions with beef imports sharply higher in 2025. Lower beef import tariffs in the latest version of spin-the-wheel trade policies will allow the market to function more effectively and may slightly moderate processing beef costs in the ground beef market. However, imports are unlikely to have much additional noticeable impact going forward and certainly will not affect the majority of beef cut prices at retail. Likewise, any sort of cattle production incentives will not speed up the time it takes to breed, grow and finish cattle for beef production. Revolving door packer investigations are unlikely to find anything different that multiple previous investigations – nothing – and, in any event, would not speed up beef production.

Under the best of circumstances, it will take 2-4 years for enough herd rebuilding to significantly increase domestic beef production. Cattle producers, already nervous and trying to deal with debilitating cattle market volatility and uncertainty, are further spooked every time politicians talk about imports, packer investigations, or any other market meddling that comes to mind. Such political talk further delays producer plans and actions to respond to market signals and start the process of herd rebuilding. Markets are remarkably efficient at fixing economic problems…when they are allowed to work. There is no quick and easy way to lower beef prices, but political rhetoric is making the process even slower. Frankly, the best thing politicians can do to help cattle and beef markets is to shut up and let the markets work. If you want to help, stop trying to help.

Mating Decisions and Gene Combination Value

Build Back Better - Replacement Heifer Series - Article 6

Mark Z. Johnson, Oklahoma State University Extension Beef Cattle Breeding Specialist

Mating decisions made in commercial cow-calf operations determine if (and how much) Gene Combination Value (GCV) we create in the next generation.

In the genetic model: Phenotype = Genotype + Environment. Genotype represents the genetic potential of an animal to reach a level of performance and can be split into two components. The component of Breeding Value (additive genetic merit) was covered last week. The focus of this article is GCV which can also be thought of as the non-additive part. GCV is based on the effect of gene pairs at loci across the genome. It is part of the animal’s genotypic value and impacts the animal’s performance potential; however, since it is based on gene pairs, it can’t be transmitted from parent to offspring. In commercial cow-calf operations we can create GCV through mating decisions. The decision to crossbreed is a mating decision.

Crossbreeding provides commercial cattlemen the opportunity to combine desirable characteristics of two or more breeds (breed complementarity) and increase performance due to hybrid vigor (heterosis). Hybrid vigor is the result of GCV.

For example, if we make the mating decision to use a Charolais bull on our Angus cows, we are creating F1 black-nosed smoke calves with 100% level of individual heterosis. Why? Because the F1 generation will have a Charolais gene paired with an Angus gene across all loci.

Hybrid vigor is the superiority in the level of crossbred offspring’s performance over the average level of the purebred parents involved in the cross. In scientific literature, levels of heterosis are typically expressed as a percentage as shown in the example below:

A Charolais bull with the additive genetic potential for 660 pounds of weaning weight is crossed with a herd of Angus cows with the additive genetic potential for 640 pounds of weaning weight. The resulting F1 crossbred calves weigh 683 pounds at weaning.

- Average of the purebred parents is 650

- The 683 pound weaning weight of calves is 33 pounds more than average of the parents

- (33/650) x 100 = 5% level of heterosis from this cross.

The 5% level of heterosis is not additive, it is the result of the biological phenomenon of hybrid vigor created by crossbreeding resulting in a GCV that is non-additive.

It is noteworthy that if the F1 heifers and bulls resulting from this cross were mated, or if we began a two breed rotation involving an Angus bull mated to the F1 females from this cross, we would lose hybrid vigor (GCV) in the resulting F2 calf crop. Why? Because not all loci would have a Charolais gene paired with an Angus gene. Hence, GCV (based on gene pairs) is NOT transmittable from parents to offspring. It must be created through mating decisions. Thereby, purebred animals are an essential component for effective crossbreeding programs.

Final Thoughts for Building GCV

Each selection and mating decision should be intentional, deliberate and made for a purpose. Selection decisions impact BV. Mating decisions impact GCV. Choose breeds (and breeding stock within those breeds) with high breeding value for traits of economic importance to your operation. Crossbreeding (to increase GCV/hybrid vigor) does not replace additive genetic merit, it builds off of it. Finally, more breeds introduced into a crossbreeding program will result in more heterosis but also increase variation. Performance levels of some traits are influenced more by additive genetic merit, other traits benefit more GCV. More on that topic next week.

Finding Forage Efficient Heifer

David Lalman and Bailey Tomson, OSU Department of Animal and Food Sciences

In recent years, substantial progress has been made in understanding biological and genetic sources of variation in feed efficiency of growing cattle consuming energy-dense, mixed diets during the post-weaning phase. In contrast, much less is known about feed efficiency of cattle consuming moderate- to low-quality forage diets. This is important because approximately 74% of the total feed required to produce beef comes from forage. Indeed, the ruminant animal’s primary advantage over non-ruminant species is its ability to convert forage—essentially sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide—into a high-quality human food source. With increased heifer retention over the next few years, perhaps now is an opportune time to consider strategies for improving forage use efficiency in replacement females.

Forage utilization efficiency has been a major research focus of our group at Oklahoma State University. Although grazing studies are ultimately the goal, we began this line of work in a controlled pen setting where forage intake can be measured accurately. Each year, we evaluate a contemporary group of weaned replacement heifers and a contemporary group of five-year-old cows. The cows are tested during lactation and again during gestation. During each test period, cattle spend approximately 90 days in our forage intake facility (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Forage intake facility at the Range Cow Research Center near Stillwater, OK.

Cattle are fed bermudagrass hay and provided mineral with free-choice access to both. The hay typically contains 12 to 14% crude protein and approximately 57 to 60% total digestible nutrients (TDN). High-quality bermudagrass hay was selected so that protein requirements of growing heifers and lactating cows are met without the need for protein supplementation. Importantly, the hay is fed unprocessed (not ground, chopped, or shredded), allowing us to evaluate intake and performance under conditions similar to many real-world forage systems.

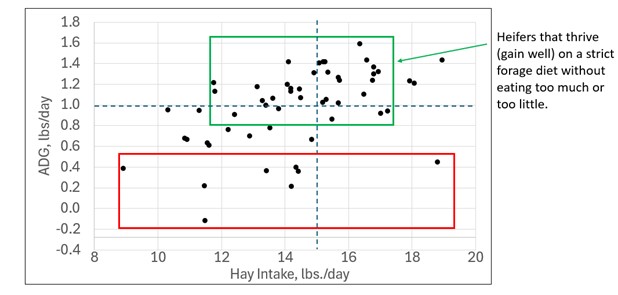

Substantial phenotypic variation is observed within each contemporary group. As an example, forage intake and weight gain for the 2024 weaned replacement heifers are shown in Figure 2. Average daily forage intake ranged from 9 to 19 pounds per day, while average daily gain (ADG) ranged from slight weight loss to gains of 1.6 pounds per day. Notably, heifers with unacceptable weight gain have been observed in every contemporary group, as indicated by the red rectangle in Figure 2. At the same time, many heifers exhibited moderate forage intake coupled with acceptable—or even exceptional—weight gain (green rectangle). Our working hypothesis is that heifers demonstrating moderate forage intake with acceptable growth will ultimately become more forage-efficient cows. Simply put, we define an efficient cow as one that is highly productive without consuming excessive amounts of forage.

In this article, we focus specifically on the forage performance (gain) component of efficiency. Our group, along with several others, has conducted experiments to determine whether cattle that rank high for weight gain when consuming an energy-dense diet (such as a bull test diet) also rank high for gain when consuming forage. To date, the answer appears to be no. Across seven independent studies, no statistically significant positive correlations have been detected between gain on concentrate-based diets and gain on forage-based diets. In fact, the average correlation across studies is near zero. These results suggest that growth performance on energy-dense diets is largely unrelated to growth performance on moderate-quality forage. Additional research is clearly needed, including larger experiments with sufficient data to estimate genetic correlations.

The encouraging news is that measuring forage-based growth performance is neither difficult nor expensive. Producers need only a reliable scale and a 70- to 100-day period during which heifers are grazing moderate-quality forage (or consuming hay) with little or no supplementation. In practice, some producers may already be selecting for forage performance—perhaps unintentionally. For example, low-input heifer development programs, short breeding seasons, and retaining only heifers that conceive early may naturally favor females that perform and reproduce efficiently on forage-based systems.

Considerable variation exists among heifers in their ability to gain weight on moderate-quality forage, and this variation appears largely independent of performance on energy-dense diets. Simple measurements of forage-based weight gain, or well-designed development programs intended to challenge heifers to perform (with minimal or no concentrate feed), and become pregnant early in the breeding season may help identify heifers that are better suited for efficient, forage-based cow-calf production systems.

Figure 2. Hay intake and average daily gain for heifers consuming bermudagrass hay.

A Record Setting Year

Scott Clawson, OSU Cooperative Extension NE Area Ag Economics Specialist

It seems like 2025 has set a record for the number of records set. From cattle prices to the average margin of victory for the OKC Thunder this season it is easy to be wowed by the numbers. While we enjoy the records, there are still some things happening in the background that we can focus on. For the OKC Thunder, I will save my thoughts for my living room! But on the livestock side, how we navigate our cost position continues to be important as our dollars don’t seem to stretch as far as they did.

Coming up in January, there will be several opportunities to focus on this issue. OSU Extension is hosting multiple cost of production workshops with the commercial cow-calf producer in mind. The workshop will work through a sample cow-calf operation going step by step how to establish an economic cost of production. Along the way, we discuss some difficult to quantify cost areas like overheads and asset purchases. We also get to look at what parts of the operation may contribute the most to the bottom line and what ones might be subtracting from it. Afterwards, attendees will have a framework to apply to their own operations.

The workshop is based on good discussion amongst the producers in attendance and is highly interactive. If you feel like the cost of being in the livestock business might be in record setting territory, this is designed to help you take a closer look. The tables below provide the specifics.

Cost of Production Workshops

Designed for the consumer beef cattle business

6 Workshops, 6 Locations. Limited to 15 participants each.

What does it cost to get a calf to weaning? What contributes the most to the bottom line? How does an equipment purchase impact the ranch? More cows? Fewer cows? Evaluate it before making the decision.

Cattle prices are at historic levels and so is the cost of getting a calf to weaning. The financial requirement to be in the cattle business continues to grow.

What is UCOP?

The Unit Cost of Production (UCOP) Workshops will show the process of finding the economic cost associated with our cattle operations. It will break down the economic cost to a dollars per pound of weaned calf level to aid in decision making.

What Will We Do?

Participants will work through the records of a sample ranch to uncover the cost of getting a calf to weaning. Along the way, participants will discuss the impacts of many ranch level decisions in areas like heifer development, bull purchases, hay production, etc.

$25 per person paid via cash or check

New Location Added! Ottawa County Extension

| Where | When | Time | RSVP Deadline | Contact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OSU Botanic Garden Ed. Center Stillwater, OK |

1/20/26 | 10 am - 4 pm | 1/13/26 | (405) 747-8320 |

| Pottawatomie Co. OSU Ext. Shawnee, OK |

1/22/26 | 10 am - 4 pm | 1/15/26 | (405) 273-7683 |

| Nowata Co. OSU Ext. Nowata, OK |

1/23/26 | 10 am - 4 pm | 1/16/26 | (918) 273-3345 |

| Pittsburgh Co. OSU Ext. McAlester, OK |

1/26/26 | 10 am - 4 pm | 1/20/26 | (918) 423-4120 |

| Okfuskee Co. OSU Ext. Okemah, OK |

1/28/26 | 10 am - 4 pm | 1/21/26 | (918) 623-0641 |

| Ottawa Co. OSU Ext. Miami, OK |

2/12/26 | 10 am - 4 pm | 2/5/26 | (918) 542-1688 |