Cow-Calf Corner | May 20, 2024

Better Pasture and Hay Conditions in 2024

Derrell S. Peel, Oklahoma State University Extension Livestock Marketing Specialist

As forage production moves into full swing, conditions for pasture and beginning hay stocks are in significantly better shape compared to last year. Released in the May Crop Production report from USDA-NASS, total U.S. hay stocks on May 1 were 21.0 million tons, up 46.6 percent year over year. That percentage speaks not only to improvement this year but just how bad last year was. The current May 1 total stocks are 8.9 percent higher than the 10-year average from 2013-2022. One year ago, the May 1 stocks were 25.7 percent below the ten-year average. The improvement in hay stocks indicates that producers generally got through the winter in better shape and still have some forage reserves going forward.

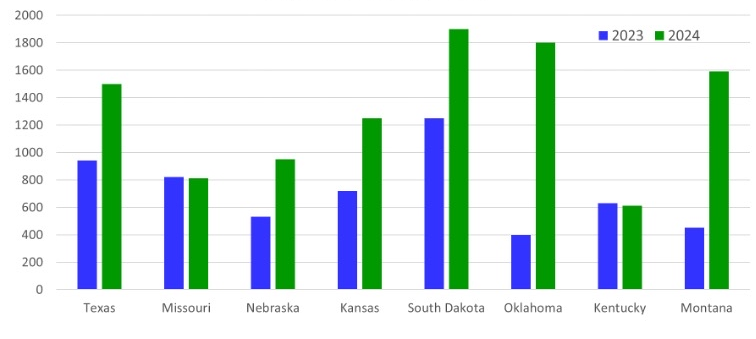

Figure 1 shows the May 1 hay stocks for the eight largest beef cow states. These states represent just over 51 percent of the total beef cow inventory of the country. May 1 hay stocks in the states in Figure 1 were mostly higher year over year, some significantly higher. Only Missouri and Kentucky had fractionally lower hays stocks this year. Hay stocks in these eight states are collectively up 81.4 percent year over year and are 9.4 percent above the ten-year average. These major beef cow states accounted for 54.0 percent of the total U.S. May 1 hay stocks.

Figure 1. May 1 Hay Stocks, 2023 and 2024. Major Beef Cow States, 1,000 Tons.

May 1 is also when USDA-NASS begins the seasonal reports on pasture and range conditions. The second report of the year for May 13 shows that the percent of U.S. pastures and ranges in poor to very poor condition was 24 percent, compared to 33 percent at the same time one year ago. At the other end of the scale, 47 percent of pastures and ranges are currently rated in good to excellent condition, compared to 34 percent last year. Regional pasture and range conditions show significant improvement year over year. The Great Plains, including Kansas, Colorado, Nebraska, Wyoming, Montana, and North and South Dakota, have 12.29 percent of pastures and ranges in poor to very poor condition, compared to 31.29 percent one year ago. The Southern Plains, consisting of Oklahoma and Texas, have 26.5 percent of pastures in poor to very poor condition this year, compared to 47.5 percent last year. The eight states west of the Great Plains region have 14.63 percent of pastures and ranges in poor to very poor condition, compared to 20.5 percent one year ago.

The U.S. currently has less drought than anytime in the last four years. The Drought Monitor includes the Drought Severity and Coverage Index (DSCI), which combines the drought categories in the Drought Monitor into a single drought measure. The DSCI can take on values from zero to 500 and the current value of 51 is the lowest DSCI since April 2020. The DSCI reached a recent peak of 202 in late 2022.

Conditions at the beginning of the 2024 forage growing season suggest that producers may be able to plan grazing and hay production with less restriction compared to recent years. However, in many cases, pastures and ranges still need time to recover from extended drought conditions. There is reason to be cautiously optimistic for better cattle production conditions in 2024. However, the forecasted redevelopment of La Niña conditions this summer is worrisome. The seasonal forecast from the Climate Prediction Center is for above average temperatures and below average precipitation for the next three months in much of major beef cattle country. Proceed with caution.

Derrell Peel, OSU Extension livestock marketing specialist, talks about volatility in the cattle markets on SunUpTV from March 11, 2024.

Spring Management Checklist

Mark Z. Johnson, Oklahoma State University Extension Beef Cattle Breeding Specialist

The commercial cow-calf business does not require intensive day-to-day management to the same extent of the other industry segments. That being said, timely management input is critical to maximizing forage production, shortening the calving season and creating profit potential. The key to capitalizing on the future value of cattle is to run your operation as a business. Managing your operation like a business means making sound financial decisions and concentrating management and labor into some of the critical control points through the annual production cycle.

As of May 2024, consider the following checklist.

- Have I made a plan for weed control, fertilizer, rotational grazing and proper pasture management? Weed control, especially on improved grasses, insures that the grass we intend to grow is making use of the moisture and soil nutrients. Applying an adequate amount of nitrogen fertilizer to Bermudagrass pastures is essential to produce the amount of forage needed to sustain your cowherd.

- Have my bulls undergone a Breeding Soundness Exam and do I have an adequate number of bulls on hand to get cows bred promptly?

- Have I given pre-breeding vaccinations and dewormed my cow herd?

- Are my replacement heifers of adequate age and target weight to breed up quick and early ahead of my mature cow herd?

- Are my cows and bulls in adequate Body Condition for the onset of breeding season?

- Based on that answer, do I need to continue with supplemental feed?

- What is my hay and feed plan for next winter?

- Have I castrated, dehorned, dewormed and given the first round of vaccinations to my spring born calves? Best management practices are to have this done by the time calves are two to four months of age.

The Importance of Cull Cow Values

Scott Clawson, M.S., Oklahoma State University Cooperative Extension Service NE Area Agricultural Economics Specialist

As I roam the two-lane highways in eastern Oklahoma going to producer meetings, cull cow prices and the decision to rebuild the cowherd are common points of discussion. In fact, if I ask who has sold some cull cows lately more smiles show up thinking about that check than anything else. The story behind the great cull cow prices has been discussed (see the March 11, 2024, edition). That leaves the expansion discussion up for grabs, and exactly what do cull cow prices have to do with it?

Much of the unease of the expansion decision is tied to the sheer size of the investment. If we decide to retain our own heifers, we will turn down a price that we have rarely seen for a weaning age heifer. Additionally, producers have reported that private treaty and special sales are fetching strong prices for bred females.

One of the most common ways to analyze an investment is to use a net present value (NPV) analysis. That is just a fancy way to say that we are going to invest in something (cow), and we expect it to generate cash (calf sales minus expenses) for a certain number of years (cow longevity) then we will salvage it (cull the cow). NPV guides us in answering the question, what is that investment worth or what should we pay for that replacement? While we process that, there are several issues to unpack. Calf prices, annual cost to run the cow, and longevity usually see the most focus and they are all important.

However, in which year of the cow’s productive life will she return the most cash to our investment? Most commonly that will be the year she is culled. In that year, she will likely calve for the last time in the spring and in the fall we will sell her and her calf. This highlights the impact that cull values can have on the math of this investment. On average, we tend to run a cow to failure. More specifically, we will keep them around until she comes up open, has a bad bag, comes up lame, etc. In those instances, we usually get the worst of what the market has to offer.

My speculation is that our current cull cow markets have changed the math from the red to the black on some cattle that we retained over the past decade while prices were more moderate, and expenses increased. Going forward, are there things that we can do to avoid getting the worst of the market? Selling as a bred, improve body condition, selling younger, etc. are all factors that we can manipulate in our culling decision and maximize the cash returned in the final year.

You can visit and use the Cow Bid Price Estimate Calculator to evaluate different options for your ranch.

USDA Moves to Electronic Identification Tags

Rosslyn Biggs, DVM, Oklahoma State University Cooperative Extension Beef Cattle Specialist

Animal disease traceability (ADT), as defined by the United States Department of Agriculture

(USDA), is knowing where diseased and at-risk animals are, where they’ve been, and

when. ADT does not prevent disease introduction, but does allow expedited emergency

response during an animal disease outbreak.

The primary ADT system in the United States is the National Uniform Eartagging System

(NUES). This system has been used for decades and is familiar to many producers although

they may not know it by name. The system is utilized when USDA official tags are required

such as when adult breeding cattle moved interstate or for program disease purposes

such as brucellosis vaccination or tuberculosis testing. Historically this system

used primarily metal visual tags, commonly called “Bangs tags” or “Silver Brite” tags.

In more recent years, both the traditional metal visual tags and certain radiofrequency (electronic) (EID) tags have been accepted as official identification. Official USDA EID tags are a 15-digit usually round/button tag that begin the tag number with the digits 840. EID tags can be read visually and with electronic readers.

Recently the USDA finalized a rule that has been under discussion for the last several years. Significant input was received from industry leaders and animal health officials. This rule moves USDA official identification to exclusively EID tags that can be read both visually and electronically starting in November 2024.

It is important to recognize that this rule change does not in any way require the mandatory tagging of all cattle. This rule change only moves USDA official identification tags from the metal option to EID tags. The classes of cattle requiring official identification have not changed. USDA official identification tags are required only under certain conditions and for certain ages and classes of cattle. The two primary situations requiring official identification are program disease testing, (such as that required for brucellosis), and interstate movement.

The cattle classes requiring identification when moving interstate are listed below. Exceptions to this requirement do apply under unique movement types, such as travel for veterinary care. Feeder cattle and animals moving directly to slaughter do not require official identification for interstate movement.

Classes of cattle requiring USDA official identification for interstate movement include:

Beef Cattle & Bison

- sexually intact and 18 months or older

- used for rodeo or recreational events (regardless of age)

- used for shows or exhibitions

Dairy Cattle

- all female dairy cattle

- all male dairy cattle born after March 11, 2013

Producers can find more information about the USDA rule change at APHIS Bolsters Animal Disease Traceability in the United States. USDA and the Oklahoma Department of Agriculture, Food, and Forestry are providing EID tags for the cost of shipping for producers needing to officially identify cattle or for herd management purposes. More information on that program can be found by calling (405) 522-6141 or at the Oklahoma Department of Agriculture, Food and Forestry.