Cow-Calf Corner | June 10, 2024

Fed Beef Production Steady; Nonfed Beef Production Down in 2024

Derrell S. Peel, Oklahoma State University Extension Livestock Marketing Specialist

Total beef production thus far in 2024 is 10.6 billion pounds, down 2.0 percent year over year. This follows a 4.7 percent year over year reduction in beef production in 2023 from record levels in 2022. Cattle slaughter in the first 21 weeks of 2024 is down 4.5 percent year over year but cattle carcass weights have averaged 21.8 pounds higher than last year thus far. Beef production will be down year over year in 2024 but by less than previously forecast. There are also some interesting dynamics across types of beef production.

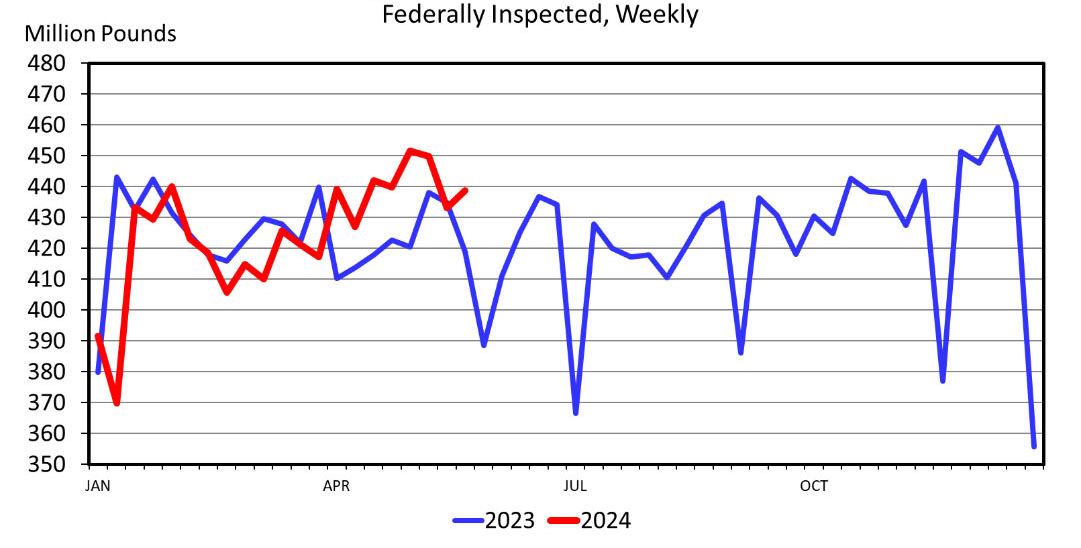

Steer slaughter is down 2.1 percent in the first 21 weeks of the year compared to one year ago. Heifer slaughter is down 1.6 percent year over year thus far in 2024. Total fed (steer plus heifer) slaughter is down 1.9 percent from last year. However, steer carcass weights have averaged 920 pounds, up 20.4 pounds this year and heifer carcasses are averaging 843 pounds, 15.9 pounds heavier year over year. Carcass weights have not shown the typical seasonal decline in the first half of the year resulting in even greater year over year discrepancies in recent weeks. Weekly data from late May shows steer carcass weights 37 pounds (heifers, 29 pounds) heavier than last year. Total fed beef production for the year to date is 8.92 billion pounds, up 0.2 percent from one year ago. Increased steer and heifer carcass weights are offsetting decreased slaughter to result in a fractional increase in fed beef production for the year to date with significant increases in recent weeks (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Fed Beef Production

By contrast, nonfed beef production is down sharply in 2024. Nonfed beef makes up 20 percent of total beef production on average. Total cow slaughter is down 14.1 percent year over year through the first 21 weeks of the year, with dairy cow slaughter down 13.4 percent and beef cow slaughter down 14.8 percent from last year. Cow carcass weights are averaging 646.8 pounds, up 10 pounds over one year ago. Bull slaughter is down 7.0 percent year over year, with bull carcass weights up 28.7 pounds over year over year and averaging 892 pounds. Total nonfed slaughter through May is down 13.6 percent and total nonfed beef production is 1.69 billion pounds, down 12.0 percent compared to last year (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Nonfed Beef Production

Fed beef will likely decline in the second half of the year. Fed slaughter is expected to decrease more in late 2024, though carcass weights will likely remain elevated. Heifer retention may be starting which would lead to a larger decline in heifer slaughter by the end of the year. Beef cow slaughter may also drop more sharply in the last part of the year. Herd rebuilding typically results in decreased heifer and beef cow slaughter. Moisture conditions through the summer and into the fall will be critical to determine if, and how much, herd rebuilding gets started and the impact on 2024 beef production.

Derrell Peel, OSU Extension livestock marketing specialist, says the recent widespread rain has given pastures a much-needed boost on SunUpTV from June 8, 2024.

The Impact of Management on the Carbon Footprint of Beef Production

Mark Z. Johnson, Oklahoma State University Extension Beef Cattle Breeding Specialist

It is possible that Oklahoma farm and ranch operations may someday pay attention to the price of carbon in the same way they track market reports of commodities and input costs. At present we do not because the price of carbon is low. That being said, in voluntary carbon markets, where buyers can choose to pay people to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, agriculture producers can earn money by participating. Even with currently low prices for carbon, the reality is that operations are playing a role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. How? Production practices such as no-till or reduced tillage, climate friendly grazing practices - such as rotational grazing or adaptive multi-paddock grazing (AMP), as well as breeding programs utilizing cows with less mature size are examples of effectively lowering the carbon footprint of beef production.

From 2011 – 2018, researchers at Michigan State University utilized AMP while examining the weaning weight of calves relative to the mature weight of cows and determined:

- Cows of smaller mature weight were more efficient. At equal body condition scores, smaller cows weaned off a higher percentage of their mature body weight.

- Smaller cows (closer to 950 pound mature weight) had a higher net present value than larger cows (closer to 1450 pound mature weight).

- The smaller, more biologically efficient cows were responsible for producing less methane per unit of land.

- They concluded that AMP led to grazing forages in the green, vegetative state, and low in lignin resulting in higher energy diets for the cattle, increased digestibility and reduced enteric methane production all of which worked together to increase soil carbon sequestration.

Management does play a role in the carbon footprint of beef production. There is still much to “sort out” in terms of carbon markets for land stewards and beef producers. Long-term, the metrics, management and monitoring of pasture and rangeland soil health has the potential to add an additional revenue stream to cow-calf producer’s earnings.

References

Blueprint For The Future – Part 2 Cattle Conference. The Impacts of Management on the Carbon Footprint of Beef. Dr. Jason Rowntree. Regenerative Ranching Panel Discussion. May, 2024

Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Fact Sheet AGEC-9501. Oklahoma Agriculture’s Role in Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions.

Using Gas-Flux Data to Estimate Dry Matter Intake for Cattle on a Grass-Hay Diet

Paul Beck, Oklahoma State University Department of Animal and Food Sciences

The 2024 Oklahoma State University Department of Animal and Food Sciences Research Summaries are currently in press, we look forward to their release in time for the Annual OCA Convention in July. The publication will provide summaries of the cutting-edge research being produced in our department. Look forward to highlights of different research in this column in the upcoming months. This week we will feature research by Emma Briggs, a PhD student working with Dr. David Lalman at the OSU Range Cow Research Center- North Range Unit, “Using Gas-Flux Data to Estimate Dry Matter Intake for Cattle on a Grass-Hay Diet”.

New open-circuit gas flux technology has allowed measurement of enteric gas emissions for cattle in a pasture-based setting. If a significant relationship exists between feed intake and gas emissions, this system could be used to rank grazing cattle for forage intake and forage utilization efficiency much easier than previous methods. Therefore, the objective of this research was to evaluate the relationship between gas emissions and forage intake using 100 Angus and Angus x Herford heifers over a three-year period.

Feeders designed to measure individual animal hay intake (C-Lock Inc., Rapid City, SD) were stocked at a rate of 3.6 heifers per feeder to ensure heifers had ad libitum access to hay. Heifers were also used for collection of gas flux data using an open-circuit, portable, gas-quantification system (GreenFeed, C-Lock Inc., Rapid City, SD) to measure oxygen consumption, carbon dioxide production, and methane production. Heat production was calculated using carbon dioxide and methane output along with oxygen intake.

Phenotypic correlations of hay dry matter intake with carbon dioxide, methane, oxygen, and calculated heat production were 0.72, 0.49, 0.64, and 0.72, respectively. Average daily gain combined with the estimate of daily carbon dioxide production accounted for 58% of the variation in DMI. Thus far, results suggest that forage intake can be predicted using the GreenFeed gas quantification system along with average daily gain. The similarity of equations developed using average daily gain plus carbon dioxide or average daily gain plus heat production (which requires measurement of carbon dioxide, methane, and oxygen) suggests flexibility in gas quantification methods used. In conclusion, these results suggest that there is an opportunity for using heifer average daily gain along with either calculated heat production or carbon dioxide as a method to rank individual animals for dry matter intake in a forage-based system.

Dave Lalman, OSU Extension beef cattle specialist, talks about OSU research that can assist with determining exactly how much a beef cow will eat on SunUpTV from May 20, 2024.