Cow-Calf Corner | July 22, 2024

Feedlot Inventories Slowly Reflecting Cattle Numbers

Derrell S. Peel, Oklahoma State University Extension Livestock Marketing Specialist

The latest USDA Cattle on Feed report showed a July 1 feedlot inventory of 11.304 million head, fractionally higher year over year at 100.5 percent of last year. June marketings were about as expected at 91.3 percent of one year ago. The marketings total seems low but June 2024 had the rare situation of having 2 less business days compared to last year, so average daily marketings in June were actually slightly higher compared to one year ago.

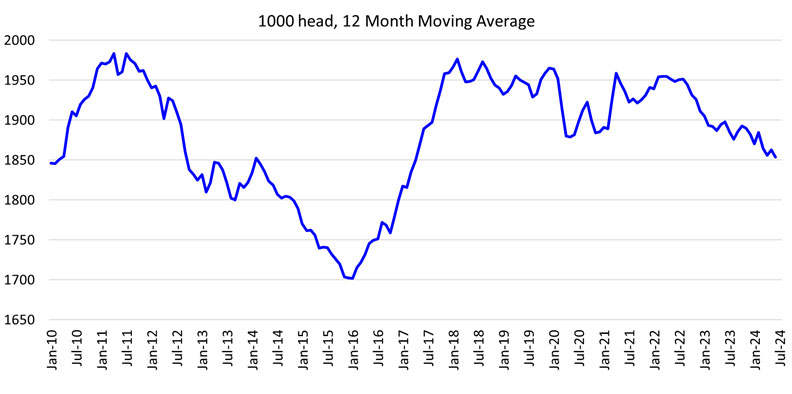

June feedlot placements were 91.2 percent of last year, slightly less than average pre-report expectations. The placement total was the smallest June total since 2016. Although the feedlot inventory has been slow to decrease, feedlots have been placing fewer cattle as feeder supplies have dwindled in recent years. The total U.S. calf crop peaked in 2018 in the most recent cattle cycle and has been declining each of the past five years. The 2024 calf crop is estimated to be another 1.5 percent smaller year over year leading to a total decline since 2018 of 8.9 percent or 3.2 million head. Figure 1 shows that average feedlot placements have decreased with the twelve-month moving-average for June at the lowest level since April 2017.

Figure 1. Feedlot Placements

The July Cattle on Feed report included the quarterly breakdown of steers and heifers in feedlots. Steers on feed was 100.8 percent of one year ago while the heifer inventory was essentially unchanged with a scant five thousand head more heifers in feedlots compared to last year. The heifer inventory confirms that heifers continue to be placed in feedlots. As of July 1, heifers make up 39.6 percent of total feedlot inventories. Figure 2 shows cyclical variation in the heifer feedlot percentage, ranging from a low of 31 percent in April 2015 to a maximum of 40.0 percent in January 2024. The current heifer feedlot percentage is near the highest levels in the past 20 years. The heifer percentage of feedlot inventories drops below the average level (36.7 percent) during periods of heifer retention and herd rebuilding and is above average during periods of herd liquidation.

Figure 2. Heifers on Feed as a Percent of Total Cattle on Feed

Proper Hay Storage

Mark Z. Johnson, Oklahoma State University Extension Beef Cattle Breeding Specialist

Proper hay storage of big round bales is important in order to minimize spoilage until time of feeding. It is worth discussing some simple storage practices that can lead to less spoilage. First, one of the few upsides of drought is that very little precipitation falls on hay stored outside. Precipitation, air temperature and humidity all lead to more spoilage in big bales. Twine wrapped bales are more subject to spoilage than net wrapped. Greater bale density leads to less spoilage. That being said, keep the following in mind when considering how your hay is stored.

Storage Site and Elevated Storage

Select a site on higher ground that is not shaded and is open to air flow to enhance drying conditions. The site should be well drained to minimize moisture absorption into the bottom of bales. Ground contact leads to more bale spoilage. When practical keep bales off the ground using low cost surplus materials like old pallets, fence posts, railroad ties and tires. Another option is a six inch layer of coarse ground rock. Anything that can be done to maximize drainage and minimize moisture within and around the storage site will be beneficial.

Orientation

Bails should be stored in rows, butted end-to-end, and oriented in a north/south direction. Avoid stacking three rows of hay in a triangle shape. This formation leads to more spoilage, particularly in the two bottom rows. North/south orientation combined with at least three feet between the rows permits good sunlight penetration and airflow, allowing for faster drying. Vegetation between the rows should be mowed.

Covers and Barns

Large round bales stored outside with plastic or canvas usually sustain much less spoilage compared to unprotected bales. If barn storage is an option, this is the best method. Dry matter losses in round bales stored for up to nine months in an enclosed barn should be less than two percent.

Summary

All forages packaged in large round bales benefit from protection and proper storage practices. Producers are encouraged to consider the cost to benefit ratio of providing this protection. Factors to consider include the value of hay, projected in-storage losses, local environmental conditions, the cost of providing protection and how long the hay will be in storage before it is fed. At the very least it may be worthwhile to restack or re-orient your hay supply according to the best practices described. Further details for estimating storage losses can be found in the fact sheet referenced below.

Reference: Oklahoma State University Extension Fact Sheet: BAE-1716

Prussic Acid Toxicity

Barry Whitworth, DVM, Senior Extension Specialist, Oklahoma State University, Department of Animal & Food Sciences

Cattle producers throughout the state have been reporting cattle losses from cyanide/prussic acid toxicity. Some producers have expressed surprise that cyanide/prussic acid is a problem since there has been an overall abundance of moisture in the state this spring. According to the Mesonet website, precipitation has been near or above normal for many parts of the state. However, as of July 1st, the same website revealed several counties that have recently been dry. These counties have received less than one quarter of an inch of rain, and during this same period, temperatures have skyrocketed. High temperatures and no rain for short periods of time stress plants. This stress leads to certain plants becoming toxic, including plants in the sorghum family.

Hydrocyanic acid (HCN), also referred to as cyanide or prussic acid, is the toxin in these plants that causes problems. The toxin is created when the harmless hydrocyanic glycosides in plants are stressed and break down. Once the hydrocyanic glycosides in the plants are damaged, they quickly convert to prussic acid which can kill an animal within minutes when consumed. When cattle ingest the plants high in hydrocyanic glycoside and break them down by chewing, the prussic acid is released in the rumen and absorbed into the blood stream. Once in the circulatory system, the toxin prevents cells in the body from taking up oxygen. The blood becomes saturated with oxygen which cannot be absorbed by the cells which is why normally dark venous blood appears bright red. The clinical signs are excitement, muscle tremors, increased respiration rate, excess salivation, staggering, convulsions, and collapse. The cattle actually die of asphyxiation.

In plants, especially in the sorghum family, prussic acid is highest in the leaves of young plants with the upper leaves containing the very highest amounts. The amount of prussic acid increases when the plant is stressed such as in drought situations or following a frost. Fertilizing with large amounts of nitrogen can also increase potential for prussic acid toxicity as does nitrogen and phosphorus soil imbalances. Certain sorghum families are more prone to prussic acid toxicity than others. For example, Johnson grass has a high potential for toxicity while Pearl or Foxtail millet are low. When planting sorghums for grazing, producers may want to check the toxic potential of the particular variety.

When producers encounter animals displaying clinical signs of prussic acid toxicity, they should immediately remove all the animals that appear normal to a new pasture and contact their veterinarian. The veterinarian will treat the sick animals that reverse the toxicity. Treatment can result in a full recovery if initiated quickly.

Producers may want to take the following steps to prevent prussic acid toxicity:

- Never turn hungry cattle into a new pasture

- Take soil samples and fertilize accordingly

- Graze mature plants

- Wait until plants are cured before grazing after frost (usually at least 7 days)

- Rotate pastures to keep cattle from consuming lush regrowth

- Place 1 or 2 cows in a pasture and observe for problems before turning in all the cattle

Plants can be tested for prussic acid, but it can be challenging. If not done properly, producers may get a false since of security. The best practice is to visit with your local veterinarian or Local Oklahoma State University County Extension Agriculture Educator before grazing forages that may contain prussic acid. A fact sheet that contains information about prussic acid is available from Oklahoma State University. The fact sheet title is Prussic Acid Poisoning PSS-2904.

Increasing the Resilience of the Beef Cattle Supply: 2. Impact of Drought on Reproductive Performance

Paul Beck, Department of Animal and Food Sciences

Last week I covered some of the impacts of drought on cow numbers and the feeder cattle supply based on comments I made at a symposium at the American Society of Animal Science meeting held in Calgary “Increasing the Resilience of the Beef Cattle Feeder Supply”. This week I will cover some additional impacts of drought and changing weather patterns on cattle reproductive performance.

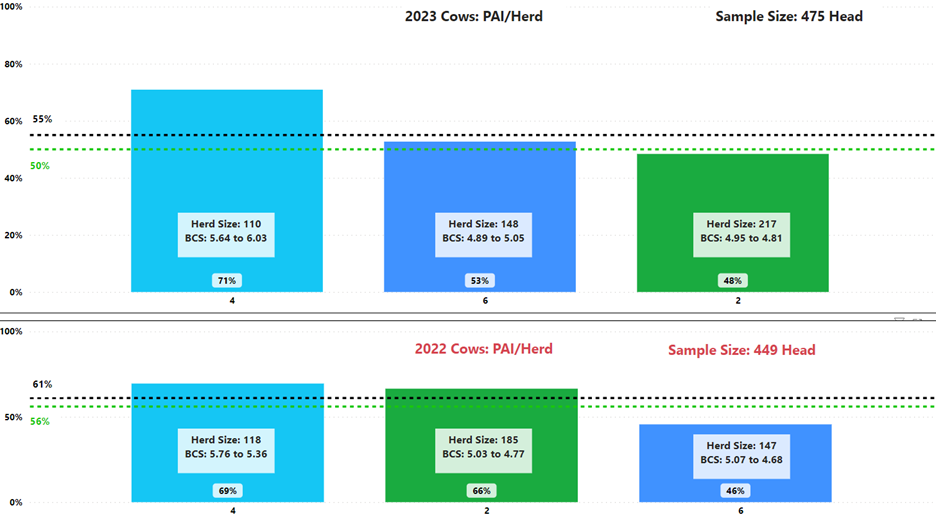

Increased culling of cows and earlier marketing of calves has triggered the decreased cattle numbers we are currently experiencing, but the drought and climatic conditions have other impacts on cattle supplies as well. Drought and climate extremes are related to reductions in forage growth and quality, and heat stress of livestock. Cows under nutrient restrictions due to the lack of available forage or forage of low nutritive quality lose body weight and body condition resulting in reduced fertility and rebreeding rates, further exacerbating the already reduced cattle numbers. Cows under heat stress and undernutrition have reduced production and quality of colostrum, impacting immune function and lifetime health and wellbeing of their progeny. Below is data from Dr. Richard Prather and Ellis County Animal Hospital showing artificial insemination pregnancy (PAI) rates from 3 herds in 2022 and 2023. Cows in herd 4 (light blue bars) were maintained in adequate body condition (BCS) in both years with excellent fertility and reproduction rates. Cows in herd 6 lost condition from breeding to pregnancy check in 2022 and had lower breeding rates, but increasing condition in 2023 improved cow fertility. While cows in herd 2 were thinner in 2023 and continued to lose condition, resulting in reduced fertility in 2023.

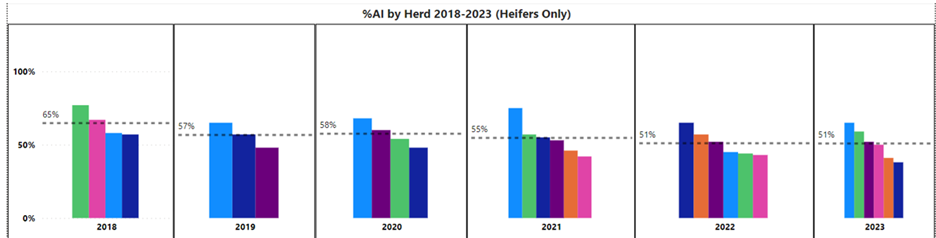

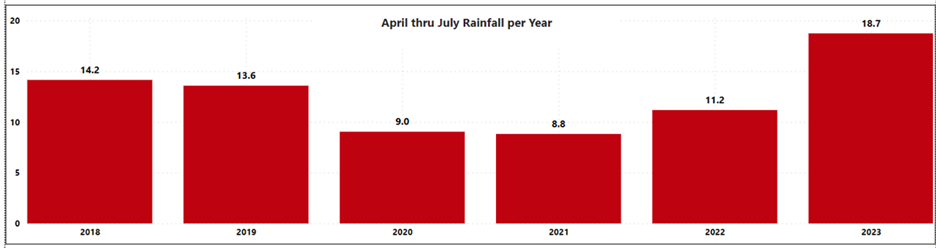

Drought and climate extremes result in disruptions in cattle supply and reduced fertility of thin cows. Along with reduced cow rebreeding rates, heat stress or nutrient restriction of gestating cows will result in long-term reductions in productivity of their offspring. The heifer offspring of undernourished cows have lower fertility and steer calves have lower performance and carcass quality at slaughter later in life. Below is the heifer artificial insemination results from Dr. Prather’s cowherd analytics along with the rainfall from April through July of each year. Average AI success in heifers from these herds declined in 2021, the year after the start of the drought in 2020 and continued to be low in 2023 even with the higher rainfall that year. This indicates that the scarcity conditions the cows were in during the drought impacted the future fertility of their offspring they were carrying. The impacts of poor nutrition can be generational.