Cow-Calf Corner | February 26, 2024

The Growing Role of the U.S. Feedlot Industry

Derrell S. Peel, Oklahoma State University Extension Livestock Marketing Specialist

The latest Cattle on Feed report pegged the February 1 feedlot inventory at 11.8 million head, just fractionally above year ago levels. Feedlot inventories are declining after rising above year-earlier levels last October. Feedlot placements in January were 92.5 percent of last year, above the pre-report average estimate but within the range of estimates by some analysts. Some analysts were expecting a larger negative impact on placements from the winter storms in January. January marketings were even with one year ago.

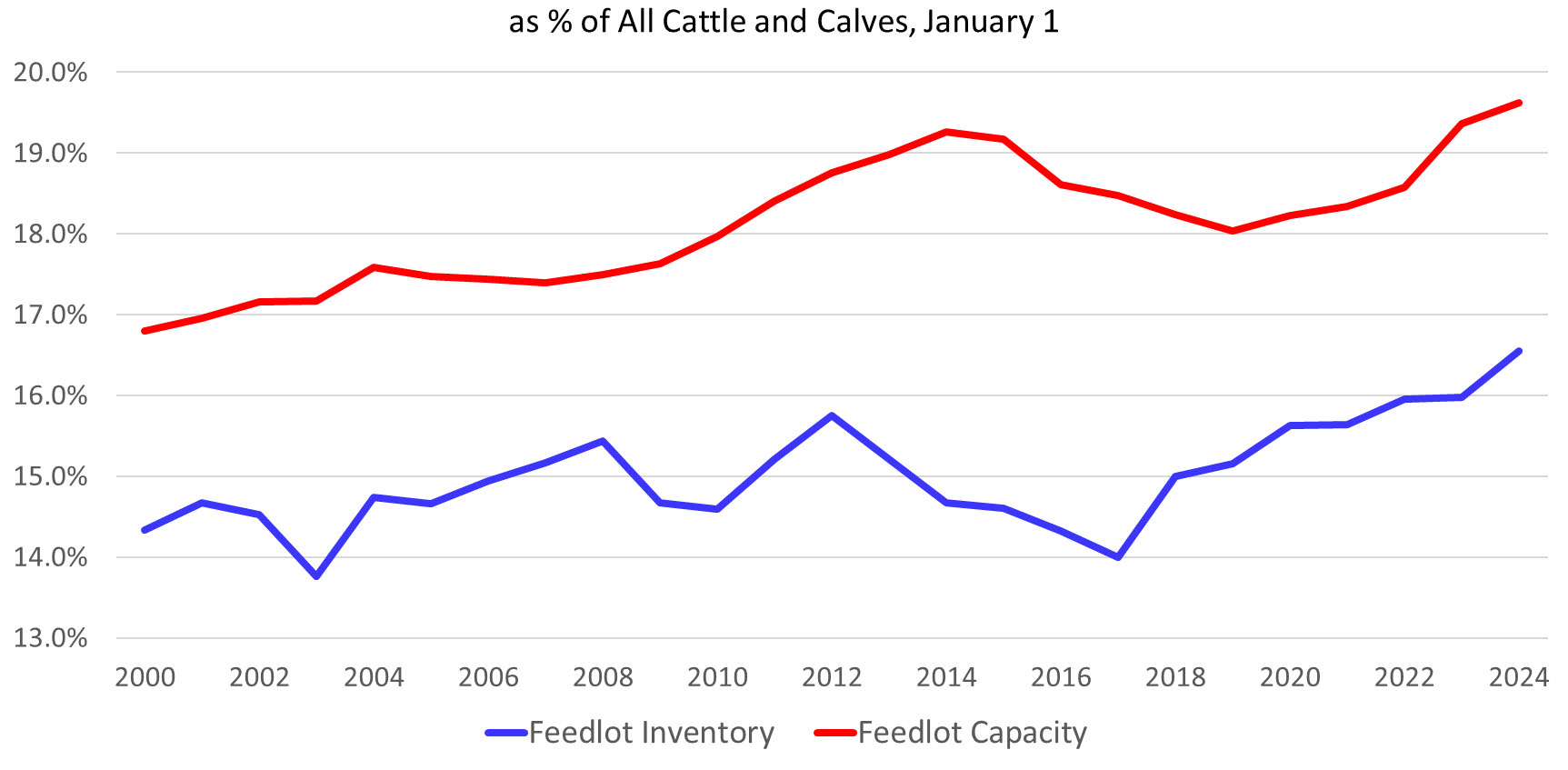

The February Cattle on Feed report also includes a summary of 2023 final feedlot numbers and feedlot industry structure. Total feedlot capacity was reported at 17.1 million head, up from 16.5 million head in 2000. Feedlot capacity as a percent of total cattle inventories has increased over the past 25 years to a record level of 19.6 percent in 2024 (Figure 1). On average feedlot inventories have averaged about 83 percent of total feedlot capacity over the past 25 years. Feedlot capacity utilization is lower during cyclical expansions and higher during liquidation periods. For example, during herd expansion from 2014-2017, average feedlot inventories were 76.3 percent of capacity, while during herd liquidation from 2020-2024, January feedlot inventories were an average of 84.8 percent of total feedlot capacity.

The total U.S. feedlot inventory on January 1, 2024 was 14.42 million head. The feedlot inventory as a percent of the total inventory of cattle in the country has continued to increase over time. The total feedlot inventory was a record level of 16.5 percent of the inventory of all cattle and calves on January 1, 2024. This level compares to 14.3 percent 25 years ago.

Figure 1. Feedlot Inventory and Capacity

The total U.S. feedlot inventory on January 1 of 14.42 million head was 120.9 percent of the January monthly cattle on feed inventory of 11.93 million head. Monthly cattle on feed surveys cover only feedlots with a one-time capacity of 1000 head or more. In the past 25 years, the total January on-feed total has averaged 122.7 percent of the monthly on-feed total. Stated another way, monthly feedlot inventory totals on average represent 81-82 percent of the total cattle on feed in the country. This relationship has not changed in the past 25 years and has varied from a low of 80 percent to a high of 82.7 percent.

The January 1 estimate of feeder supplies outside of feedlots was 24.2 million head, down 4.2 percent year over year and the lowest total in data available back to 1972. The current feedlot inventory is a record 59.6 percent of feeder supplies. Stated another way, this means that there are just 1.68 head of feeder cattle for every head of cattle currently in feedlots. The current feedlot turnover rate is about 1.93, which means that there are not sufficient feeder cattle to maintain feedlot inventories in the coming year. Feedlot inventories will inevitably decrease in the coming months.

Derrell Peel, OSU Extension livestock marketing specialist, discusses the cattle markets on SunUpTV from February 24, 2024.

Selection of Replacement Heifers

Mark Z. Johnson, Oklahoma State University Extension Beef Cattle Breeding Specialist

Low cow herd inventories, historically high calf prices, looking for the first hollow stem, breeding season just a month or two away and the recent USDA Cattle Inventory report shows a tight supply of beef replacement heifers. All leading to the topic of selection criteria for replacement heifers. Selecting the heifers that will have the optimum mature size and milk level to fit our production system, breed quickly, wean a calf annually and have longevity is important. What should we consider when selecting yearling heifers as replacements?

Early Puberty

The younger a heifer begins to cycle, the better her chances of conceiving in time to calve by 24 months of age. Early puberty is moderately to highly heritable and positively related to future reproductive efficiency. Reproductive tract scoring can be used to evaluate puberty status. Typically, reproductive tract scoring is done four to six weeks prior to breeding season and serves as a tool to indicate reproductive readiness to conceive.

Fertility

Heritability estimates of fertility are extremely. But because reproduction is so economically important, it should be a priority in heifer selection. Realistic goals for heifers would be 60-70% first service conception rate and 90-95% bred after a 60-65 day breeding season. Heifers should be held accountable and culled if they don’t meet these standards. Keep in mind, early preg checking of replacement heifers permits opens to be marketed at yearling prices. Over time, culling the heifers that don’t get pregnant in a defined breeding season will result in a cowherd with more fertility. Furthermore, heifers that calve in the first 21 days of calving season have increased longevity and wean more pounds of calves over their lifetime. Keeping 5 – 10% more heifers than needed for breeding, permits you to cull the sub-fertile heifers and maintain adequate replacement heifer inventory moving forward.

Milking Ability

Research clearly indicates the optimum level of milk production in a beef herd is relative to the forage/feed resources available in their production environment. Milking ability is low in heritability. The most effective means of selecting for an optimum milk level is through the use Milk EPDs on the sire. Keeping heifers from heavy milking cows comes with the risk of heifers getting overly fat prior to weaning. When this happens, the heifers subsequent milk production may suffer due to fat deposits in the developing mammary system.

The Mammary System

While difficult to assess the mammary system of virgin heifers, it is important to avoid heifers with teats that are barely visible and appear embedded in hair or fatty tissue. When possible consider the udder and teat structure of the dam who produced the heifer.

Disposition

Disposition is reported to be moderate to highly heritable. Culling heifers with bad dispositions will improve the ease of herd management, producer safety and conception rates.

Body Type/Fleshing Ability/Muscle Thickness/Structural Soundness

Heifers that are easy fleshing typically are structurally sound, have a wider structural frame and a body type of more rib shape and depth. Heifers with this body type will be heavier muscled. Evaluating replacement heifers for structural soundness should include the evaluation of feet, legs and eyes as soundness contributes to longevity in production. Fleshing ease equates to breeding females that better maintain body condition and energy reserves on a given amount of feed.

Growth Rate

Heifers with good growth rate and of moderate frame size should make the best cows. Those that are extremely light, extremely heavy or too large framed at a given age should be culled. Commercial cow-calf producers sell pay weight and replacement heifers with more growth should transmit this advantage. That being stated, much like milk, there is an optimum mature cow size relative to the production environment. Keep in mind, puberty is a function of age and weight. The target weight of yearling heifers is 65% of their mature size.

Calving Ease

Measuring the Pelvic Area (PA) of yearling heifers and considering the Calving Ease Maternal (CEM) EPD of sire can be used as selection tools to reduce dystocia. PA is typically measured in square centimeters. As general rule of thumb, dividing the yearling PA by 2.1 indicates the size of calf (in pounds) she should be able to deliver unassisted. For example: a yearling heifer with a PA of 175/2.1 = 83, indicating she should be able to deliver a calf of up to 83 pounds. CEM EPDs predict the likelihood of a bull’s daughters delivering their first calf unassisted. For example: a heifer sired by a bull with a CEM of 15 is 11% more likely to calf unassisted than if sired by a bull with a CEM of 4.

As importantly, sire selection of the bulls to mate to virgin heifers is of paramount importance in reducing the incidence of dystocia. Calving ease bulls will have lower Birth Weight (BW) and higher Calving Ease Direct (CED) EPDs within their respective breed.

Final Thoughts

Selecting the oldest heifers has long been considered an effective method of identifying replacements produced by the earliest calving cows. Heifers born late in the calving season or less than 13 months old at the onset of their first breeding season will be more challenged to breed quickly.

References

Angus The Business Breed, Sire Evaluation Information

Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology

The Value of Calving Distribution

Scott Clawson, OSU Cooperative Extension NE Area Agriculture Economics Specialist

Commercial cow-calf producers can face an overwhelming number of records, data, and ratios that promise to boost the bottom line. Hidden in these options is one simple measure that can provide useful information about the cowherd’s performance that we can start tracking today. That measure is our calving distribution. Calving distribution is simply tracking when our calves are born within our calving season.

This measure is useful in three areas.

- There is a litany of research that emphasizes the improved individual animal performance of calves born early in the calving season. Better weaning weights, stronger feedlot/carcass performance, and improved reproductive efficiency of retained heifers are all well documented research.

- It helps us identify which females are excelling within our environment and management by settling early in the breeding season.

- It can help us identify which cows are making the largest annual profit contribution to the ranch. It is common to discuss annual cow cost or cost per cow. This is a bit misleading in the sense that we manage the herd not the individual. As a result, the cows all share an equal part of the annual cost. The cows that calve early in the season will bring in more revenue (via older and generally heavier calves) than the late calving cows that share the same portion of the cost.

The collection of information to do this is simple. Start by tracking the dates that calves are born and split your calving season into segments. The by the book method is to use 21-day increments. Take the number of calves born in that segment and divide it by the total calves born. The answer will provide the percentage of calves born in that period. The target is to get as many cows calving in the initial 21-days as feasibly possible.

While making progress can be slow, diagnosing our current distribution and finding cost effective ways to front load our calving season can have significant financial benefits. In the commercial cow-calf setting, calving distribution is a go-to production measure for its ease and the information it provides. It highlights that while she needs to have a calf every year, that calf needs to hit the ground earlier rather than later.