Cow-Calf Corner | December 2, 2024

U.S. Imports of Mexican Cattle Disrupted

Derrell S. Peel, Oklahoma State University Extension Livestock Marketing Specialist

The November 22, 2024 announcement that New World screwworm was detected in southern Mexico resulted in the temporary suspension of live cattle imports from Mexico. This raises many questions about the implications this might have on U.S. cattle markets. Some history and context are helpful to understand the potential impacts.

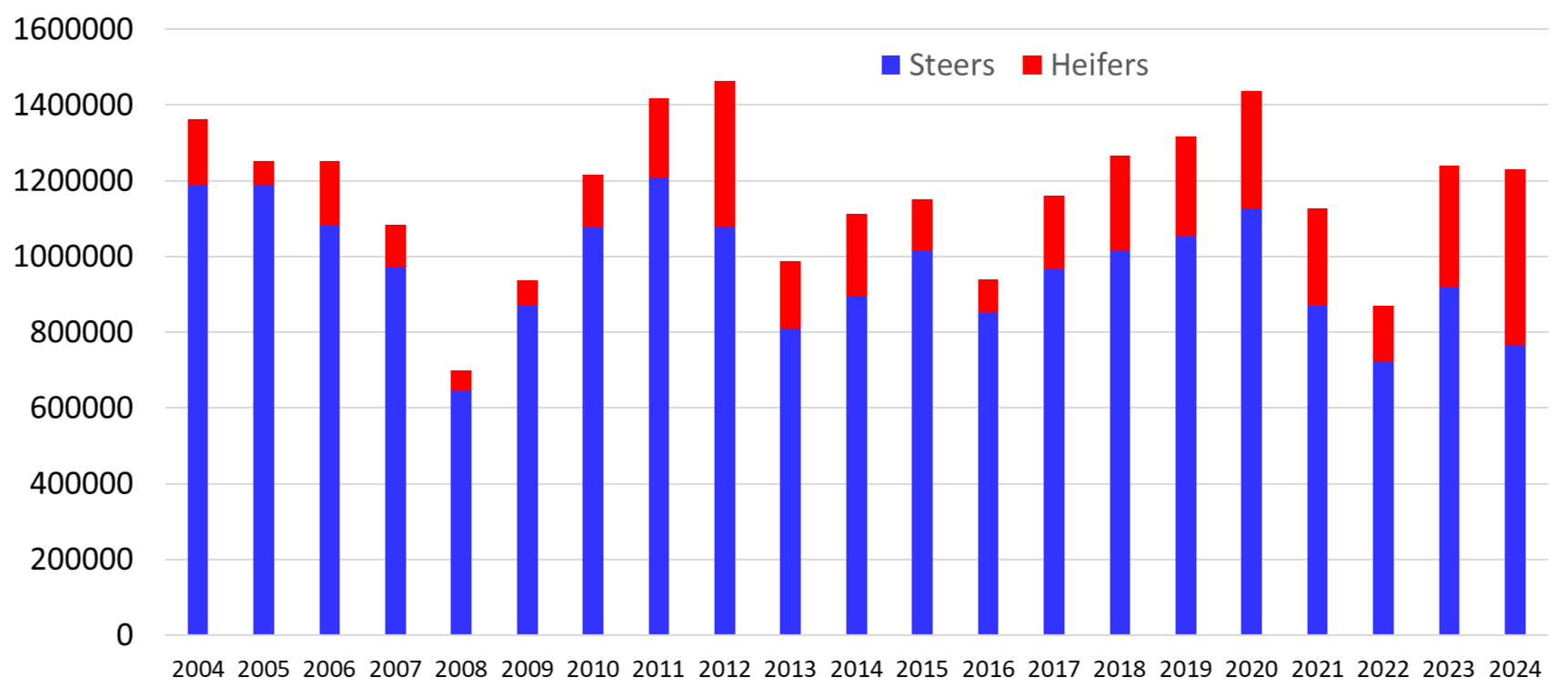

An average of 1.17 million head of Mexican cattle were imported into the U.S. in the 20 years from 2004-2023, ranging from a minimum of about 703,000 head in 2008 to a maximum of 1.47 million head in 2012 (Figure 1). Mexican cattle imports represent 3.3 percent of the total U.S. calf crop on average. Figure 1 also includes 2024 preliminary weekly imports through the first 47 weeks of the year. Imports of Mexican cattle have averaged 84.5 percent steers and 15.5 percent spayed heifers over the past 20 years (Figure 1). However, in the five years from 2019-2023, the percentage of heifers increased to an average of 21.3 percent.

Figure 1. Cattle imports From Mexico

Feeder Steers and Heifers, Head (2024 partial)

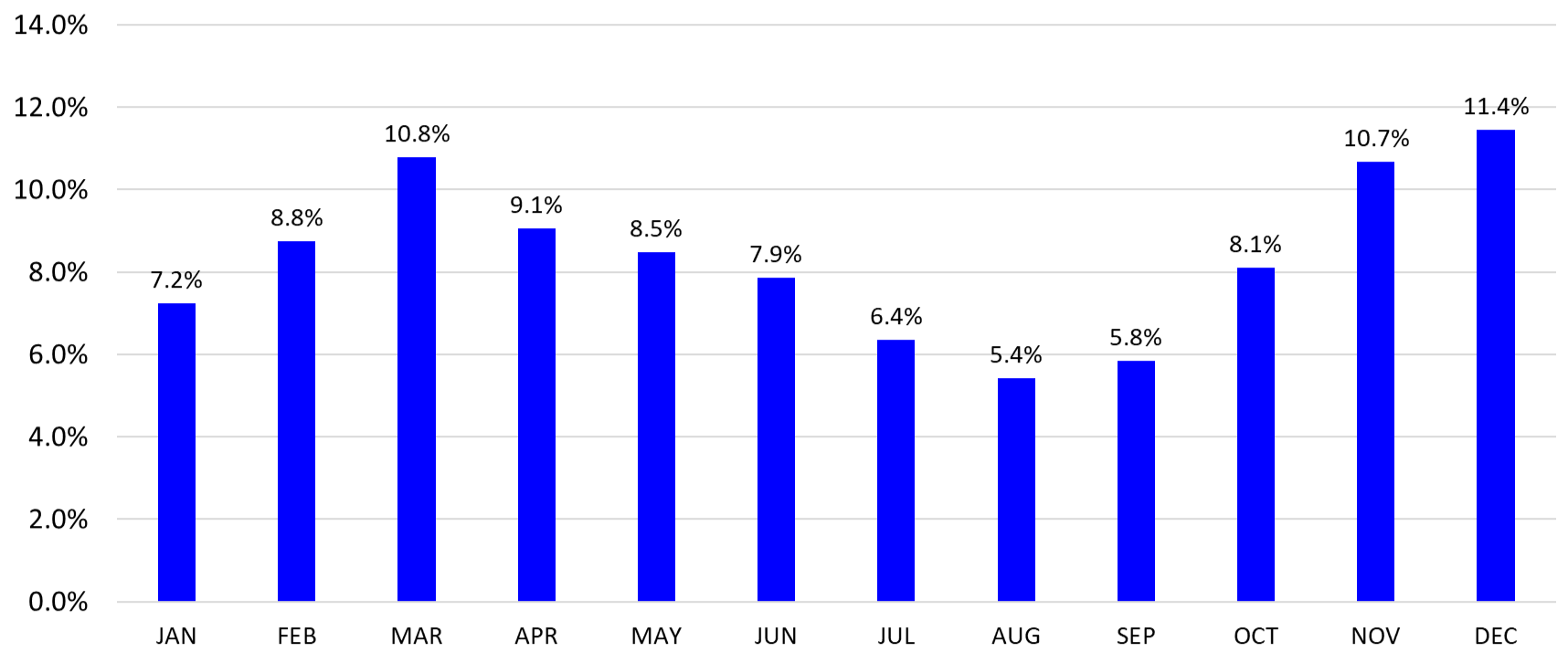

Figure 2 shows the average seasonal pattern of Mexican cattle imports for the last five years. Mexican cattle imports have maintained a relatively stable seasonal pattern for many years with peak months in the spring and in November/December with lows in summer. In recent years the seasonal pattern has equalized slightly with fractionally lower peak months and higher summer lows. However, the pattern remains as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Seasonality of Mexican Cattle Imports

Percent of Annual Imports, Average Monthly, 2019-2023

USDA has indicated that the border is expected to be closed at least three weeks from the late November announcement. Protocols are being developed for a partial opening of the border (New Mexico and Arizona ports) which will include a pre-export inspection of all cattle; treatment for insects; and a seven-day quarantine, followed by the usual border inspection and crossing process. It seems likely that few, if any, additional Mexican cattle will be imported in 2024. The 2024 import value in Figure 1 is based on the preliminary weekly data through November 23 with a total of 1.24 million head. This may well be very close to the import total for the year.

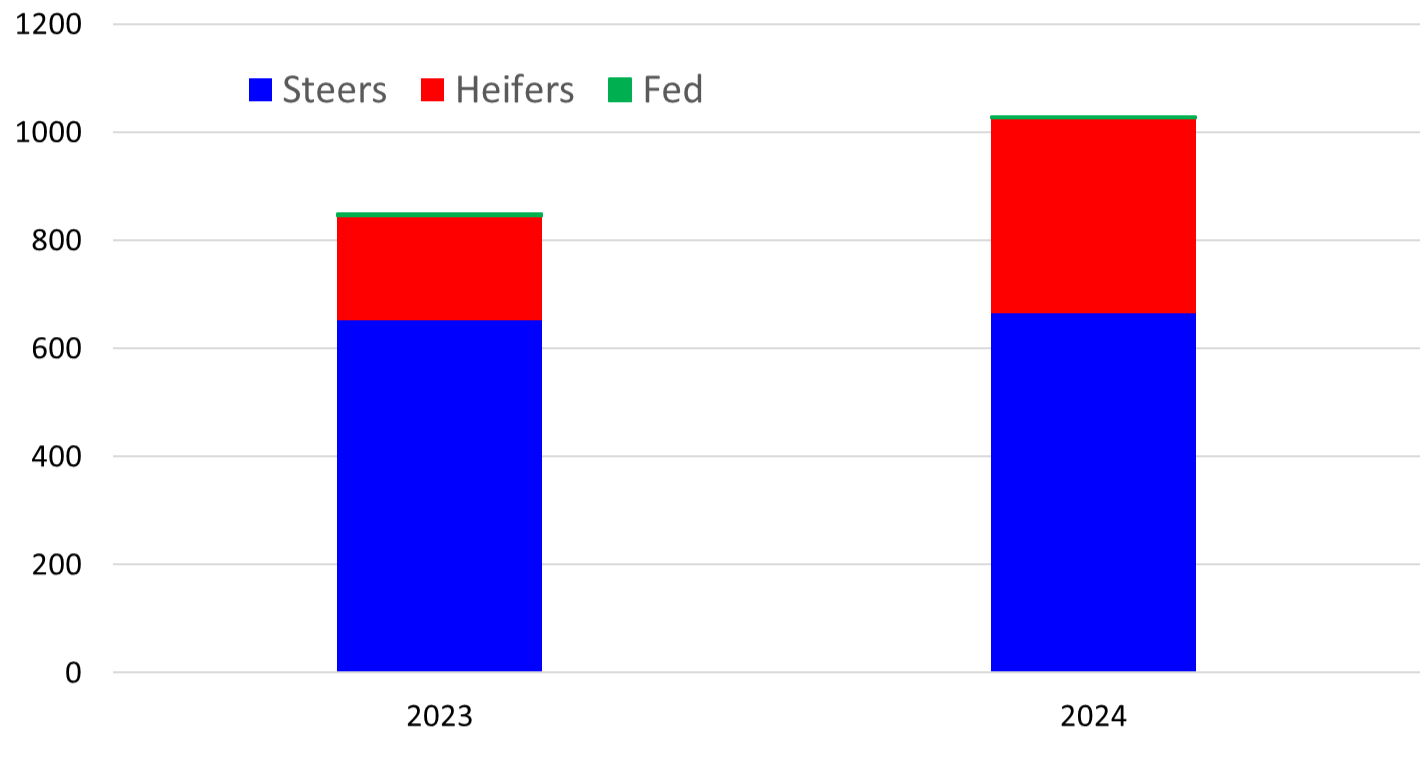

Figure 3. U.S. Imports of Mexican Cattle

January - September, 1000 Head

Figure 3 shows the year-to-date monthly official import totals through September. Imports of Mexican cattle were up 21.3 percent year over year for the first nine months of the year. The pace suggested that total annual imports could be about 1.5 million head. Most of the increase was due to additional spayed heifer imports, up 87.2 percent year over year and accounting for 35 percent of total cattle imports.

Figure 2 shows that November and December typically account for roughly 22 percent of annual imports. Assuming no imports for the last week of November and all of December and given the pace of imports thus far in the year, it is likely that annual imports will be reduced by 200,000 - 250,000 head from the probable total before the screwworm announcement.

The lack of Mexican cattle imports for the remainder of the year will have some immediate impact reducing an already tight feeder supply. However, some of the feedlot impact is not immediate because a portion of the imported Mexican cattle are lightweight and typically go through stocker/backgrounding programs before feedlot placement. In the January – September period this year about 24 percent of the imported cattle were less than 200 kilograms (441 pounds). It’s important to remember that most of the cattle not imported for the remainder of the year will enter the U.S. eventually…just with a delay. As long as the current situation does not drag out excessively or result in some permanent changes in import regulations, the primary feeder cattle market impact will be a change in timing with a short-term tightening of supply and the delayed cattle arriving in the coming weeks/months.

Monitoring Nutrition Requirements of the Cowherd

Mark Z. Johnson, Oklahoma State University Extension Beef Cattle Breeding Specialist

Knowing the nutritional needs of our cows helps us cost effectively meet their needs. Over feeding or underfeeding both rob the profit potential from cow-calf operations. During the normal production cycle cows should gain some weight/body condition during the dry stages and lose some weight/body condition while nursing a calf. With that in mind, having cows at a BCS 5 – 6 going into calving season is optimum. This means that cows are in good shape and have ample energy reserves to draw upon when the “spike” in Crude Protein (CP) and energy (TDN) requirements occur post-calving as the cow begins lactation. Cows need to be in good shape at the beginning of calving season to reduce the rebreeding interval and stay on schedule to breed, calve and raise a calf to weaning each 12 months.

Assuming we have an ample supply of good quality water and an adequate vitamin/mineral supplementation program, the two primary nutritional requirements of cows are CP and Energy (in the form of TDN). In normal weather, there are three primary influences on the daily requirements of both:

- Mature Weight

- Level of Milk Production

- Stage of Production

Cow-calf operations should assess where their cowherd is now in the production cycle and be proactive in making management decisions regarding feeding and supplementation. The example below follows a 1,300 pound cow through a normal production cycle during the middle trimester of pregnancy, the final trimester of pregnancy, and the first 90 days post-calving based on her level of milk production.

During the middle third of pregnancy, the 1,300 pound mature cow needs:

- CP = 1.64 pounds per day

- TDN = 11 pounds per day

The same 1,300 pound cow in the final third of pregnancy needs:

- CP = 1.84 pounds per day

- TDN = 13.3 pounds per day

The increased nutritional needs reflect not only the cow’s maintenance requirements but also the increased growth and development of the fetus as calving draws near.

After calving, during the first 90 days of lactation, the same 1,300 pound cow will have increased nutritional requirements based on how much milk she is producing.

If giving 25 pounds of milk per day at peak lactation, she will need:

- CP = 3.4 pounds per day

- TDN = 19.3 pounds per day

If giving 35 pounds of milk per day, she will need:

- CP = 4.2 pounds per day

- TDN = 22.2 pounds per day

In summary, the same cow has a dramatic rise and fall in protein and energy needs over the normal production cycle. Knowing these requirements is essential to cost effective feeding of the cow herd. Managing our nutritional program correctly plays a huge role in reproductive performance and cow productivity. More details about nutritional requirements of beef cows can be found in the fact sheet referenced below.

Reference: Nutritional Requirements of Beef Cattle. OSU Cooperative Extension Fact Sheet E-974.

Mark Johnson, OSU Extension beef cattle breeding specialist, discusses how to calculate how much hay cattle producers will need in the winter on SunUpTV from October 26, 2024.

Predicting Performance of Finishing Steers

Paul Beck, Oklahoma State University Beef Cattle Extension Nutritionist

When we are considering keeping some calves through finishing, it would be great if we had an idea about which ones we should keep, and which ones should be marketed to let someone else take the risk of feeding them. Commercial labs have developed genomic testing to determine the genetic merit of livestock by a simple tissue or blood test. The use of genomic testing of feeder cattle prior to feedlot entry may allow for feedlot managers to make enhanced management and marketing decisions or can allow producers to make informed decisions regarding retained ownership of a portion of their calves through finishing.

We conducted research at OSU to determine the predictive value of these tests on postweaning performance and efficiency. This research project utilized the Igenity Beef Index (Neogen, Lansing, MI) to determine its predictive value for performance of beef steers post-weaning. The Igenity Beef Index provides a score on a scale of 1-10 for 17 maternal, performance, and carcass traits. The objective of this study was to determine differences in performance and efficiency of finishing steers utilizing Neogen Igenity Beef scores for average daily gain (ADG). Spring born commercial Angus steer calves from the OSU Range Cow Research Center [n = 83; body weight (BW) = 924 ± 70.3 lb] were placed on feed at the Willard Sparks Beef Research Center on May 5, 2022, after grazing wheat pasture for 155 d. The steers were allocated by scores for genetic growth potential into Low Growth (ADG scores 1 - 4), Medium Growth (ADG scores = 5 - 6), or High Growth (scores = 7 - 10) gain feeding groups based on Igenity Beef ADG Score.

There were no differences in daily gains during preconditioning or while grazing wheat, so there was no difference in initial finishing bodyweight due to Igenity ADG scores. There were no differences in intake or gain during the step-up period between entry into the feedyard and starting of the final finishing diet. Steers with High Growth scores gained weight more rapidly during finishing and weighed more at harvest than steers with Medium Growth and Low Growth steers. Growth score was shown to influence feed intake during finishing with High Growth steers consuming more feed than Medium Growth or Low Growth steers. But High Growth steers were more efficient in utilizing feed due to their greater performance. Steers with High Growth scores had greater hot carcass weights than Medium Growth and Low Growth steers. These data indicate that Igenity ADG scores can be used to select cattle with improved performance, feed efficiency, bodyweight at harvest, and hot carcass weight without impacting carcass quality grade.