Cow-Calf Corner | August 5, 2024

Two Scenarios for Beef Herd Expansion: Slow; and even Slower

Derrell S. Peel, Oklahoma State University Extension Livestock Marketing Specialist

Coming into 2024, the beef cow herd is at a 63-year low – the smallest beef cow inventory since 1961. This has pushed cattle prices to record levels through 2023 and 2024. And yet, there are no indications that any beef herd rebuilding is underway. The question of rebuilding the beef cow inventory is fundamental for cattle markets in the next few years.

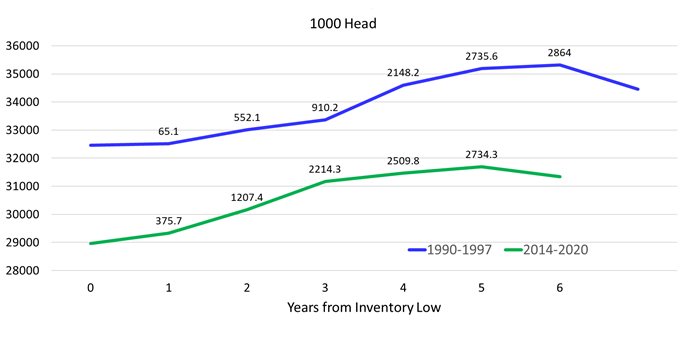

A review of historical herd expansions is instructive. Figure 1 shows the path of beef cow herd increase for the past two complete cyclical expansions. From 1990-1996, the beef cow herd increased by 2.864 million head. From 2014-2014, the beef cow herd increased less – by 2.734 million head – in one less year but faster. The beef cow herd increased by 1.2 million in just two years from 2014-2016.

Figure 1. Historical Beef Cow Herd Expansion

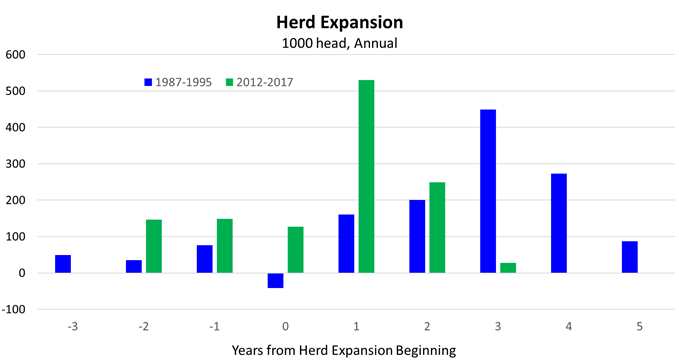

One of the keys to herd expansion is heifer retention. Figure 2 shows the changes in beef replacement heifer inventories leading to and during herd expansion. Beef replacement inventories increased three of four years prior to the beginning of herd expansion in 1991 and for three years prior to herd expansion in 2015. Both expansions included one year of very large heifer retention (year 3 in 1993 and year 2 in 2015) with smaller increases before and after.

History provides some insight into what to expect in the next few years. First, is the fact we do not yet have a zero year (low inventory) from which herd rebuilding can begin. Beef cow slaughter is sharply lower, down nearly 16 percent year over year thus far in 2024. However, that level of beef cow slaughter, combined with the low beef replacement heifer inventory in 2024 (Figure 3) implies that the beef cow herd continues to liquidate by another 0.5 – 1.0 percent in 2024. Beef cow slaughter would have to drop by roughly 22 percent year over year to avoid additional liquidation this year. The current rate of beef cow slaughter indicates a herd culling rate in excess of 10 percent this year. The culling rate is expected to drop below 10 percent during herd expansion. Thus, 2025 is the earliest zero year for the next expansion to begin. There is no certainty that additional liquidation will not occur in 2025.

Figure 2. Change in Beef Replacement Heifers during Herd Expansion

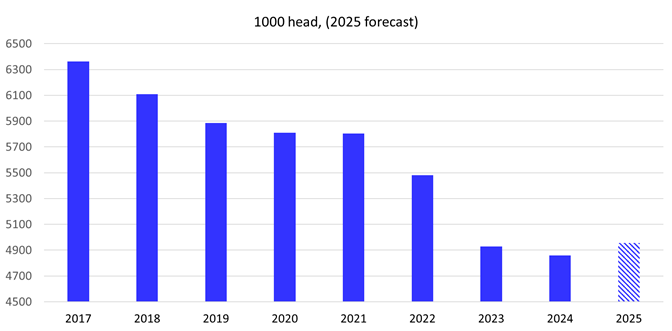

Figure 3 shows the level of beef replacement heifer inventories since the cyclical peak in 2017. Liquidation of beef replacement heifer inventories in recent years means that there is no pipeline or momentum for herd expansion compared to previous expansions. Moreover, the level of heifer slaughter and heifers in feedlots in 2024 suggests that the replacement heifer inventory in 2025 is likely to show modest growth at best. Figure 3 shows a projected 2.0 percent year over year increase in beef replacement heifers in 2025. At that level, the beef cow herd is limited to stable numbers or very minimal increase in 2025. Beyond 2025, heifer retention could increase more and accelerate herd expansion beginning in 2026. Current conditions do not suggest a high likelihood of sharply accelerating heifer retention anytime soon.

Figure 3. Beef Replacement Heifers

The threat of continuing/redeveloping drought is one of the factors limiting the beginning of herd expansion at the current time. Should developing drought conditions become a reality in the coming months with the return of La Niña, additional herd liquidation is likely, and any herd rebuilding could be pushed off further into the future. The beef cattle industry is smaller than needed and signals for rebuilding will continue and growth in coming months. However, herd rebuilding is likely to be slow to start and proceed quite slowly initially.

Is It Time To Wean?

Mark Z. Johnson, Oklahoma State University Extension Beef Cattle Breeding Specialist

As of August 1, 2024 the Mesonet Oklahoma Drought indicates over 69% of Oklahoma is abnormally dry. Of that percentage over 25% of our state is rated in moderate to severe drought. One potential management solution to dwindling forage resources in cow-calf operations is weaning calves.

The average age of beef calves weaned in the United States is a little over 7 months of age. While calves can be weaned as early as 60 days of age, this comes with quite a bit of added management. Simply weaning calves one to two months early is a cost effective management strategy that saves body condition score (BCS) and allows thinners cows (falling below BCS of 4) to more easily recapture flesh before having their next calf. When the nutritional demands of lactation are removed by weaning there is significant reduction (15 – 20%) in the dietary energy needed by cows. Saving BCS on cows now comes with the potential benefit of improved cow productivity in the years that follow. Weaning earlier than normal is most beneficial in years when pasture forage is inadequate to support herd nutritional requirements. From the standpoint of range management, it reduces the risk of overgrazing and accordingly adds to the long-term health of the grazing system.

If you plan to wean earlier than normal to alleviate stress on cows and pastures, keep the following management practices in mind:

- The first two weeks post weaning are a critical time for calves to overcome weaning stress, maintain health and become nutritionally independent by learning to consume feed.

- Lower the risk of health problems and promote calf growth by giving proper vaccinations prior to weaning. Castrate and dehorn calves when giving pre-weaning vaccinations. This permits calves to deal with the stress of these management practices while still nursing.

- Get calves accustomed to a feed bunk and water trough as quickly as possible (if not prior to weaning). Creep feeding calves for a few weeks prior to weaning will ease the transition and get calves accustomed to concentrate feed. Maintain access to good quality, clean water at all times.

- Fence line wean if possible. This eliminates stress by permitting calves to remain in the same pasture where they are familiar with feed, water, shade, etc.

- The feed ration is critical because feed intake is initially low after weaning. It needs to be highly palatable, nutrient dense, dust free and include a complete vitamin and mineral supplement.

- After calves are over the stress of weaning they should begin to consume approximately 3% of their body weight in high quality feed each day. Feed intake variation or depressed appetite can indicate health problems.

- Shade is important if weaning during summer heat.

Management Strategies to Increase the Resilience of the Beef Cattle Supply

Paul Beck, Oklahoma State University Extension Beef Cattle Nutrition Specialist

In recent weeks I discussed the impacts of drought and climate disturbances on cattle numbers, cow fertility, and lifetime productivity of calves. This week I am covering some of the ways we can improve the resilience of our production systems to drought and other climate disturbances.

Matching Environment and Cow Biological Type

Research from the USDA ARS Southern Plains Experimental Range in Harper County Oklahoma from the late 1950’s and 1960’s indicated that the economically ideal stocking rate was 0.07 animal unit equivalents per acre. For the 1,000-pound cows common at the time this was 14.5 acres per cow. Since then the cow mature bodyweight has increased by 7 pounds per year, with current cow mature weights of 1,350 pounds. Where cows are still stocked at 14.5 acres per cow, the actual stocking rate has been increased by 25% to 0.086 animal units per acre. While cow size has increased by 350 pounds over the last 60 years, calf weaning weights have only increased by 66 pounds. With increasing resources (precipitation, fertilizer, feed, etc.) the potential for a ranch to maintain a larger cow with a higher level of milk production increases. As cow mature weight and level of milk increases costs, level of management, and risk also increase.

Flexible Stocking

Flexible stocking is not a new concept; it is common practice by many ranches in harsh environments in the western U.S., but many producers have lost sight of this system as we become more specialized in our production. If we stock the ranch with the optimal number of cows for drought years, additional forage resources could potentially be used for an alternative enterprise during years of plenty. These alternative enterprises could be a stocker operation, custom grazing for other producers, or hay production. In drought years, we can cut back on the alternative enterprise and use the excess acres for maintaining the cowherd. This would make it possible for the ranch to keep from purchasing large quantities of hay at a high price or increased culling of the cowherd at a low price.

Improved Grazing Management

Research in Arkansas (Beck and others, 2016; doi: 10.2527/jas.2016-0634) looked at the effects of improving grazing management by integrating multiple strategies including rotational grazing, stockpiling bermudagrass, and planting a few acres of cool season annuals into bermudagrass pastures on cow-calf productivity and hay feeding requirements. During years with normal precipitation hay was only fed to cows in the pastures with improved grazing management during periods of ice and snow cover of the standing forage (less than 3 days per year) compared with 90 days in the continuously grazed pastures. During drought years cows in continuously grazed pastures were fed hay for 140-days, compared with only 40 days for cows in pastures with improved grazing management. Improving grazing management was able to reduce reliance on stored forages and improve forage stand persistence during drought conditions.

There are multiple ways we can change our management to improve our operation’s resilience to drought. Integrating multiple alternatives may be the best way to counter the predicted changes in our environment to maintain long term sustainability.