Cow-Calf Corner | October 30, 2023

Winter Wheat Grazing Hopes Revived

Derrell S. Peel, Oklahoma State University Extension Livestock Marketing Specialist

Most of Oklahoma has received significant rain in the past week reviving hopes for wheat pasture. The majority of the state was blessed with 1.5 to over 6 inches of rain. Only the northwest and panhandle regions missed out this time.

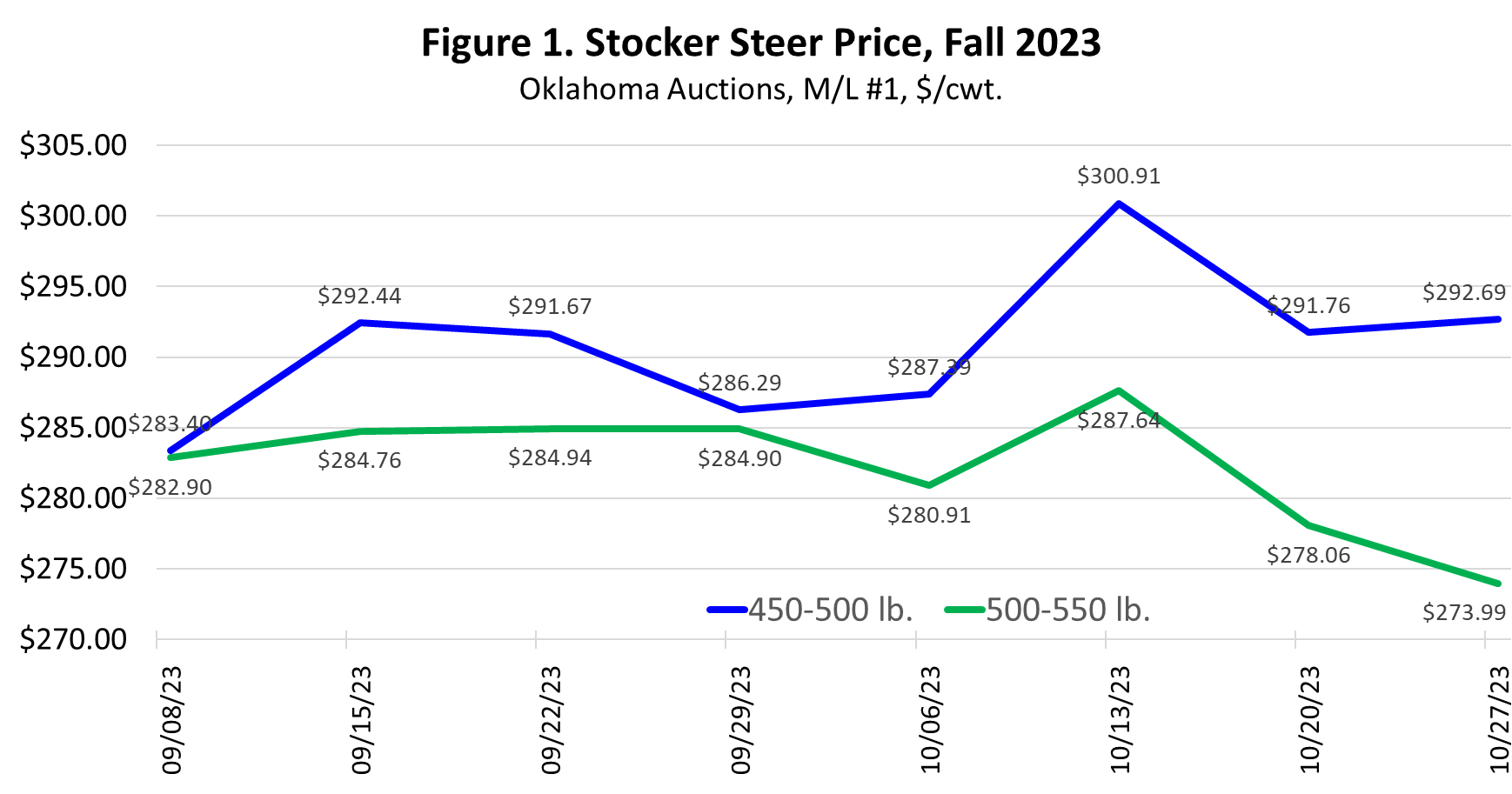

Wheat stands around the state are quite variable with some bigger wheat all the way down to wheat barely emerged. The latest Crop Progress report shows that 71 percent of Oklahoma wheat is planted, two percent more than last year but less than the 75 percent 5-year average. In recent extension meetings, many producers have indicated that they expect to have wheat pasture, if somewhat later than usual in many cases. Some producers have already purchased stockers, betting on the come, while others will be in the market now. Figure 1 shows prices for stocker steers this fall in Oklahoma. Prices for the preferred stockers under 500 pounds have not decreased seasonally this fall. In fact, average prices for 450-500 steers in October were higher than September. Prices for heavier feeder cattle over 600 pounds have decreased about 10 percent in recent weeks.

Both Live and Feeder futures have seen a huge downward correction in the past six weeks after months of trending higher. Both markets have dropped precipitously in the last half of October but appear to be stabilizing now. A profit-taking correction is not surprising and has been made worse by recent global events and enhanced market volatility. March Feeder futures are currently priced at about $238/cwt., down from roughly $255/cwt. just two weeks ago. Current cash and futures prices imply a value of gain from November 1 to early March of about $1.50/pound for a 475-stocker steer. Depending on specific cost assumptions, this is about equal to the breakeven for winter grazing, providing returns to wheat pasture and labor but nothing beyond that for the cattle. If feeder futures rebound somewhat, as I expect, there may be better opportunities to lock in additional returns in the coming weeks.

Reduced feeder auction volumes reflect the decreasing supplies of cattle in the country. Oklahoma combined auction feeder volume is down 10.6 percent year over year thus far in 2023. The auction volume has been down every week for the last ten weeks and is down 14.7 percent compared to the same period one year ago. The biggest weekly volumes of the year typically occur in the next six weeks but are likely to remain below year-ago levels. With smaller volumes and stronger wheat pasture demand, stocker calf prices are unlikely to show any seasonal weakness in the coming weeks and may move higher, depending on the impact of broader market uncertainty and volatility.

Advocacy

Mark Z. Johnson, Oklahoma State University Extension Beef Cattle Breeding Specialist

Advocacy is defined as "public support for or recommendation of a particular cause or policy."

Only 2% of US citizens work in production agriculture. It is a foregone conclusion that virtually everyone reading this article is among that 2%. Therefore, we understand where food comes from, that beef cattle under our care and management have a higher standard of living than if they were released back into the wild. That beef production serves as a great example of sustainability and over the long-term the grazing ecosystem (consisting of soil, plants and cattle) can and does flourish when managed according to science and good animal husbandry. The point of this week's topic is to help understand that the other 98% of our population are far removed from production agriculture and therefore have a limited understanding of that knowledge. Two to three generations ago, a much larger share of the U.S. population was directly involved in the production of food. As a result of our efficiency, technology and good management in a free enterprise economy, US citizens spend a smaller percentage of their disposable income on food than any other country in the world. Our high degree of efficiency has resulted in only 2% of our population being "needed" to produce food. The beef industry is not unique in this respect. The dairy, grain production and poultry industries have all dramatically improved production capabilities and efficiently over the past 50 - 60 years. The efficiency of production agriculture has created the perception that food can be taken for granted. Our business plan should include helping consumers (the other 98%) understand beef production and advocating for our industry.

How do we advocate for our industry?

- Share your story. Engage with people and build relationships. Production agriculture is a way of life as well as a business. Connect and communicate your story, tell others about your business, what you do and the industry you are a part of.

- Get involved. Join your county, state or national cattlemen's association. Information about the Oklahoma Cattlemen's Association and The National Cattlemen's Beef Association can be accessed on their websites.

- Earn your MBA! The Masters of Beef Advocacy is your go-to program for training and resources to be a strong advocate for the beef community. This is a free, self-guided online course which can be accessed here.

Change is inevitable. The drovers and cowboys involved in the cattle drives along the Chisholm Trail during the 1870s when America acquired a taste for beef, would not recognize the beef industry of 2023. The perseverance, adaptability and hard work of American cattlemen has permitted the beef industry to sustain, survive and thrive for 150 years while meeting the consuming public's demand for our product. It is our responsibility to represent our industry and tell our story.

As cattle producers we care for animals that are capable of taking fibrous plants (undigestible by humans) and turning them into a nutrient dense, healthy and delicious food for mankind. Embrace the opportunity to share your story and advocate for your industry.

Supplementation Options when Wheat Pasture is Short

Paul Beck, Oklahoma State Extension Beef Cattle Specialist

Prospects for wheat pasture started off in good shape this fall with many areas getting late summer rains. However, most of the wheat grazing areas did not get adequate rains to push the emergence and growth of wheat pasture for most of the month of September and October. Most of the region got nice rains that will likely drive enough forage production on early planted wheat for grazing by mid-November or early December. Later planted wheat or wheat that had not emerged from earlier plantings will probably be severely delayed even with the latest round of precipitation in October.

What can we do to sustain stocking rates that support at least approaching our normal levels of production?

Setting stocking rates on wheat pasture in the fall and winter has large impacts on performance of growing calves and can have large influences on productivity of pastures during the spring. We have found that the maximum ADG could be expected at 5.0 pounds of forage dry matter per pound of initial calf bodyweight and ADG and if the initial forage allowance is restricted to 2.4 lb forage DM/lb initial calf bodyweight we can still see adequate performance of around 2 lbs/day. If forage allowance falls below 2 pounds of forage dry matter per pound of calf bodyweight, supplementation should be considered. If we use an average of about 200 pounds of forage per inch in plant height, a good stand of wheat that is 4 inches tall (800 pounds of forage dry matter per acre) will require stocking rates of about 2.5 to 3 acres per 500-pound steer for adequate season long performance.

Research from the OSU Wheat Pasture Research Unit at Marshall showed that providing a concentrate supplement (based on either corn or a soyhull/wheat middling blend) containing monensin at 0.65 to 0.75% of body weight (for example, 4 pounds per day for a 533-pound steer) increased potential stocking rate by 33% and weight gains by 0.3 pounds per day. This supplementation program can also be used to "stretch" wheat forage when pastures were 60 to 80% of normal, allowing for "normal" stocking rates. Recently, we stocked steers on wheat pastures at forage allowances of either 1.5 or 3 pounds of forage DM/pound of steer bodyweight with or without 3.3 pounds per day of a wheat middling/soyhull feed blend. Steers on the higher forage allowance (3.0 lbs forage DM/ lb steer bodyweight) with supplementation gained the most (3.8 lbs/day) while unsupplemented steers on the higher forage allowance gained 3.6 lbs/day. Supplementation increased gains more for steers at the lower forage allowance where gains of steers stocked at forage allowance of 1.5 lbs forage DM/lb steer bodyweight increased from 2.5 lbs/day to 3.2 lbs/day with supplementation.

Intake of low-quality roughages is not high enough to offset wheat forage intake and can reduce performance of growing calves. Research has shown that offering moderate to high quality roughages such as corn silage or sorghum silage or round bale silages can be used to replace short wheat pasture or double stocking rates on wheat pastures. Early research showed that feeding corn or sorghum silage daily to calves on wheat pasture allowed stocking rates to be increased by up to 2X without reducing steer performance. We repeated this research by offering bermudagrass round bale silage to steers stocked at 1, 1.5 or 2 steers per acre with forage allowances going from 2.9 to 1.2 lbs forage/lb of bodyweight. Offering round bale silage at the lowest stocking rate actually increased gains compared with steers at the same stocking rate without silage (3.15 vs 2.79 lbs/day). As we increased stocking rate, average daily gain decreased, but total gain per acre increased by 52%.

There are some feeding options available to us when the economic conditions are right, but forage conditions are lacking. Feeding either limited concentrate supplement or moderate quality roughage during the fall can increase production stability and thus improve economic stability of the wheat stocker enterprise. There does not appear to be economic advantage of feeding stockers grazing spring wheat when producers decide to forgo wheat grain harvest and steers graze out the wheat crop.