Cow-Calf Corner | May 22, 2023

Here We Go Again

Derrell S. Peel, Oklahoma State University Extension Livestock Marketing Specialist

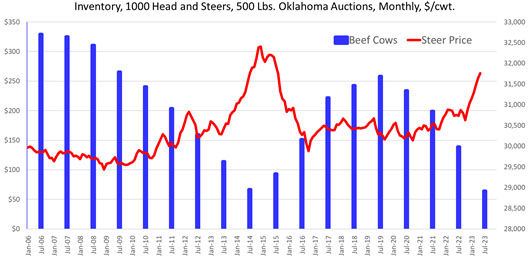

For the second time in a decade, drought has pushed cattle numbers in the U.S. lower than planned and lower than needed to meet the demands of the market. Figure 1 shows how the current situation is similar to the beginning of the previous low in beef cow numbers.

Cattle prices are trending higher, starting to increase much as they did in 2013 prior to the herd rebuilding that commenced in 2014. However, while drought has diminished in much of the country, important beef cattle regions in the central and southern plains that are still in drought limit how the cattle industry is able to respond. Beef cow slaughter is falling so far this year, usually the first sign of ending liquidation and stabilizing the cow herd. However, with the year more than one-third over, cow slaughter is down about 11 percent year over year and that is not enough of a decrease to ensure the end of herd liquidation. In 2014, beef cow slaughter dropped just over 18 percent from the previous year to put the brakes on herd liquidation. I suspect that the ongoing drought is masking continued liquidation in some areas up to this point. While signs are encouraging that the drought will continue to fade through the year, more beef cow herd liquidation is likely in 2023.

Figure1. Beef Cow Inventory and Steer Prices

The supply of bred heifers on January 1 was down 5.1 percent year over year to the lowest inventory since 2011. The low bred heifer inventory combined with the relatively slow reduction in beef cow slaughter makes additional beef cow herd liquidation this year probably unavoidable. In other words, if drought conditions continue to improve, 2024 will probably be the low point of the herd similarly to 2014, albeit at even lower beef cow inventories. The peak in cattle prices in 2014, extending into 2015, precipitated record heifer retention in 2015 and 2016 that pushed the beef cow herd higher.

The supply of replacement heifer calves (available to be bred this year) on January 1 was very low, suggesting that the ability to add heifers next year may be limited. However, some heifers not reported as replacements typically get bred and that number may increase this year. Nevertheless, the overall supply of heifers remains limited. The inventory of heifers in feedlots remains high, though it is declining. Thus far, heifer slaughter in 2023 is fractionally higher year over year on top of the large heifer slaughter level last year. Heifer slaughter in 2022 was 30.6 percent of total cattle slaughter, the highest proportion since 2005. Heifer slaughter is expected to decrease through the year but, like beef cow slaughter, at a relatively slow rate. What all of this means is that heifer retention likely will begin in earnest this fall with heifer calves to be bred in 2024. Modest herd expansion is possible next year with faster herd expansion after 2024.

Analyzing Your Production System and Strategic Use of Genetic Prediction

Mark Z. Johnson, Oklahoma State University Extension Beef Cattle Breeding Specialist

Cow-calf operations should analyze their production system and critically evaluate the following:

- your cattle and their current level of performance.

- your production environment.

- your fixed resources and management.

- your production inputs and marketing endpoints.

Careful evaluation of your production system permits you to identify the traits of primary economic importance. It is easy to find superior genetic potential in many bulls and many breeds. That genetic potential will only increase the profit potential of your operation if it is offered for the traits is primary economic importance to your operation.

What is an Expected Progeny Difference (EPD)?

An EPD is a prediction of how future progeny of a parent are expected to perform relative to the progeny of other animals. EPDs are expressed in the unit of measure for that trait, plus or minus. EPDs are based on:

- Performance of the individual animal we are looking at relative to the contemporary group of animals it was raised with.

- The performance of all the animals in the breed’s database which have pedigree relationship to that animal. Including all ancestors, siblings, cousins, offspring, etc.

- Genomics, whereby the DNA of the animal is analyzed to identify if the animal carries genes known to influence quantitative, polygenic traits like birth weight, weaning weight, yearling weight, etc.

EPDs are the result of genetic prediction, based on performance data collected by cattle breeders over many generations of beef production. This performance data is submitted to respective breed associations and statistically analyzed accounting for pedigree relationship to yield EPDs. EPDs are an estimate of an individual animal’s genetic potential as a parent for a specific trait.

Accuracy Values (ACC) are reported along with each EPD to reflect how much information has been taken into account in calculating the EPD. Accuracy values range from 0 to 1.0, values closer to 1.0 indicate more reliability. Accuracy is impacted by genomic testing as well as the number of progeny and ancestral records included in the analysis. The more information taken into account in calculating the EPD, the higher the ACC value associated with that EPD.

An example of comparing two potential sires and our selection priority is to improve weaning weight:

Sire A has a Weaning Weight EPD of 65.

Sire B has a Weaning Weight EPD of 50.

If mated to the same cows, the calves by Sire A should weigh 15 pounds more at weaning (65 – 50 = 15).

Virtually all beef breeds publish a Sire Summary. Sire summaries include a great deal of useful information. This would include the definitions of each of the EPDs reported by that breed and how the EPDs can be used to benefit your operation.

Mark Johnson explains expected progeny difference and tells us how it is used in the cattle industry

Biosecurity: Do You Have a Plan?

Rosslyn Biggs, DVM, OSU State Extension Beef Cattle Veterinarian

Biosecurity is a commonly used term in animal health circles. Simply stated biosecurity measures are those practices taken to prevent the introduction of disease into an animal population and spread of disease within an existing group. Biosecurity focuses on both infectious and non-infectious concerns. Many farms and ranches may have incorporated biosecurity practices for decades, but not necessarily considered those practices under the umbrella of biosecurity. The foundation of good biosecurity is good animal husbandry.

Cattle producers, veterinarians, and animal health officials have long known the benefits of good biosecurity practices in relationship to overall health for individual animals as well as state and national herds. Food safety, profitability, marketability, business continuity, and consumer demands are all reasons to consider developing or reevaluating a herd’s biosecurity plan. Additionally, biosecurity is important for animal welfare, environmental stewardship, and judicious use of pharmaceuticals.

Cattle producers, veterinarian, and animal health officials have long utilized biosecurity plans in national efforts to eradicated diseases such as brucellosis and tuberculosis. Biosecurity plans can apply to national plans to prevent foreign animal and emerging diseases just as they apply to an operation with forty cows or even a youth show project. However, biosecurity plans are not one size-fits-all.

Three key principles are found in every biosecurity plan: 1. the identification of a biosecurity manager, 2. A written operation-specific plan, and 3. the establishment of a line of separation. These three principles provide the foundation of a customized plan for a specific operation.

For many operations, biosecurity efforts are usual everyday practices that just simply need to be put down on paper and reevaluated as necessary. It may be helpful to have a veterinarian or another individual familiar with biosecurity take a fresh look at the plan annually. OSU’s Beef Cattle Manual, the Beef Quality Assurance program, and Secure Beef Supply offer great reference material for those writing plans, as well recommendations for reevaluating a plan’s effectiveness.

OSU Extension beef cattle specialist Rosslyn Biggs discusses the importance of practicing safe biosecurity with livestock during the fair season on SunUpTV.