Cow-Calf Corner | July 19, 2021

Feeder Cattle Markets Adjust to Higher Feed Prices

Derrell S. Peel Oklahoma State University Extension Livestock Marketing Specialist

Rising feed prices continue to be reflected in feeder cattle markets. Market prices for feed grains increase in order to ration feed demand to balance with a limited supply. High feed prices is a market signal to all feed users to use less grain. For the pork and poultry industries this is a signal to reduce production, which is the only way monogastric animals can reduce feed use. For the cattle industry, high feed prices does not mean that less cattle will be fed and produced… certainly not for many months. The supply of feeder cattle adjusts only slowly with annual calf crops. High feed prices encourage the cattle industry to utilize the ruminant flexibility of cattle to change how cattle are fed.

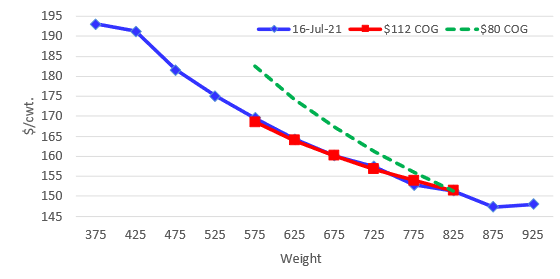

Figure 1 shows the current average auction prices for Oklahoma feed cattle ranging from 375 pounds to 925 pounds (blue line). The set of feeder cattle prices at any point in time reflects a variety of factors including the overall supply of feeder cattle, fed cattle prices, feed and forage market conditions, time of year and other factors. The price level for big feeder cattle (right side of the graph) is mostly a function of expected fed cattle prices and the supply of big feeder cattle relative to feedlot production flows. Feedlots have flexibility to purchase and place cattle of varying weights in the feedlot. The cattle industry adjusts to high feed grain prices mostly by focusing on buying heavier feeder cattle that will require less feed to finish. Thus, high feed prices have relatively little impact on the price of big feeder cattle but a significant impact on the price of lighter weight feeder cattle relative to big feeders.

Figure 1. Price-Weight Relationship. (Medium/Large No. 1 Steers, Oklahoma)

In Figure 1, the red line shows approximately how a feedlot is willing to price lighter weight feeder cattle relative to an 825-pound animal, in the current market, when feedlot cost of gain (COG) is $112/cwt. The red line lies on top of the blue market price line, which indicates that the feeder market currently reflects roughly this level of feed costs. The green line shows approximately how feedlots would price lighter weight feeder cattle if feedlot cost of gain was at 2020 levels, roughly $80/cwt. In other words, the price of lightweight feeder cattle would be significantly higher relative to heavy feeders with lower feed costs and the market line would be steeper and would be close to the green line.

This illustrates how the cattle industry responds to high feed grain prices and how the market adjustments coordinate the industry response outside of feedlots. The feeder cattle market responds to high feed prices by reducing the premium of lightweight feeders to heavy feeders as feedlot prefer to buy more pounds from the country. This represents a reduction in the price rollback or price slide for feeder cattle as weight increases. The result is to increase the value of gain for stocker production and thereby encourage cattle to achieve more weight prior to placement in the feedlot. More emphasis on stocker production also slows down the movement of cattle into the feedlot and reduces feed demand by spreading out feeder cattle over more time. The current value of gain for stocker production based on the market prices in Figure 1 is $1.05 to $1.10 per pound of gain for steers from 450 to 900 pounds.

High feed prices mostly impact how cattle are produced. In an environment of high feed prices the industry incentives are to make cattle bigger before feedlot placement and to slow down the rate of cattle production somewhat. For cow-calf and stocker producers, this means more opportunities for retained stockers and stocker production to heavier weights in response to those market signals.

Summer Mineral Nutrition

Paul Beck, Oklahoma State University Extension Beef Cattle Nutrition Specialist

Mineral nutrition is complex, with different macro minerals (required as percentage of diet) and micro minerals (required in ppm of diet) that are of concern. Our forages also do not stay the same in mineral composition throughout the year, and differ by region of the state. In addition, cattle in different stages of production have different minerals that we need to keep in mind.

Minerals that we most often have issues with include sodium (provided by salt), calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, cobalt, copper, and zinc. Minerals are involved in all aspects of the animal’s life. Calcium, phosphorus, and copper are important for bone strength and development. Calcium and magnesium are essential in nerve and muscle function. Phosphorus has roles in energy metabolism, cell membrane structure, and rumen microbe growth and function. Cobalt, copper, and zinc have roles in immune function. Deficiencies of phosphorus, copper, and zinc result in reduced fertility.

- Salt is always deficient in forage based diets.

- Calcium should be at a 1:1 to 3:1 ratio with phosphorus, but 7:1 can be tolerated.

- Phosphorus is one of the more expensive ingredients in mineral mixtures. It is important not to short on this mineral when it is needed even when the mineral costs more!

- One of the first visible symptoms of a copper deficiency is a dulling of the hair coat, but deficiencies have probably already affected immune function and growth before this sign shows up.

- Research shows zinc supplementation improves hoof and eye health.

Native range pastures are often deficient in sodium, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, cobalt, copper, and zinc for both growing stockers and cows. A 12% calcium 6% phosphorus mineral mixtures providing highly available micro minerals works well for growing stocker calves. Cows need a 12% calcium, 12% phosphorus mineral to meet requirements.

In well-managed bermudagrass pastures, phosphorus is often only marginally deficient or adequate, but calcium can be variable, ranging from deficient to adequate. Zinc is often sufficient in bermudagrass. In Eastern Oklahoma, highly weathered soils with low pH and mineral antagonists (molybdenum is a primary culprit) often results in copper deficiency. For growing stocker calves and lactating cows, minerals should provide salt (18 to 20%), calcium (12%), and trace minerals from highly available sources such as copper sulfate (copper oxide is not digestible). Phosphorus can be included at lower levels.

- Red salt blocks (or Trace mineralized salt) are not good sources of micro minerals and usually do not provide sufficient mineral concentrations or quality to meet cattle’s needs.

- Watch the suggested consumption of minerals fed. Mineral mixtures are available that recommend 2 ounce per day consumption, but many require 4 ounce consumption. Monitor mineral consumption to ensure adequate intake.

Testing New Additions to the Herd

Rosslyn Biggs, Oklahoma State University Extension Beef Cattle Veterinarian

The addition of any new animal creates the potential for introduction of disease into the resident herd. One way to help prevent new disease introduction is by working with a veterinarian to develop a protocol. The protocol can specify the required testing of all new additions to the farm or ranch whether purchased, leased, or borrowed, as part of their written operational biosecurity plan.

A plan for testing new additions will likely be based on a producer’s willingness to accept the risk of disease introduction combined with the known prevalence of disease, geographic origin of cattle, and the seller’s provided or guaranteed health history. It is always best for buyers to request a written health history of the prospects. Vaccination status, deworming history, reproductive evaluation, and specific disease testing should be considerations.

For additions of new bulls, buyers should require written documentation of a timely breeding soundness evaluation (BSE) conducted by a veterinarian following the standards established by the Society for Theriogenology (SFT). Sampling for reproductive infectious diseases such as Tritrichomonas foetus and Campylobacter fetus should also be strongly considered for all non-virgin bulls.

The addition of replacement females also requires assessment of reproductive parameters. Reproductive tract scoring may be a helpful evaluation when considering replacement heifers. If the female has been artificially inseminated or exposed to a bull, confirmation and stage of pregnancy should be determined. Testing for reproductive infectious diseases may also be warranted.

Depending on pedigree, buyers of bulls and replacement females may also want DNA marker testing for heritable diseases causing genetic abnormalities. Although these diseases are not infectious, the introduction of these genetics by even a single sire or several closely related females can have a significant negative impact.

Introduced infectious diseases have the potential to negatively impact the entire herd. Producers may want to discuss testing for diseases such as bovine viral diarrhea and Johne’ disease with their herd veterinarian.

Even if a new introduction receives a clean report after testing and shipment, it is still recommended that the animal undergo a minimum two week isolation before exposure to the resident herd as part of a good biosecurity plan. Following the protocol developed by the herd veterinarian will help prevent the introduction of new diseases and protect the producer’s investment.