Cow-Calf Corner | April 26, 2021

April Cattle on Feed Report Not Easy to Understand

Derrell S. Peel, Oklahoma State University Extension Livestock Marketing Specialist

The April USDA Cattle on Feed report requires careful interpretation. The typical year to year comparisons are mostly meaningless because of the pandemic disruptions affecting markets one year ago. Comparisons to 2019 are more helpful to correctly understand the implications of this report. The on-feed total for April 1, 2021 was 11.897 million head, 105.3 percent of last year’s pandemic reduced level. The total is 0.5 percent lower than the 2019 level for the same date.

Feedlot placements in March were 128.3 percent of last year. However, the 1.997 million head total for March was 0.8 percent smaller than the March total for 2019. The March placement total likely did include some increase in placements pushed into March by the February winter storm. Nevertheless, the placement total was not only smaller than pre-report expectations but was somewhat bullish in an absolute sense. March marketings were 2.04 million head, 101.5 percent of one year ago; seemingly small given that there was one additional March business day this year. However, the 2020 March marketing number was unusually large. The 2021 March marketings number is 14.8 percent larger than the 2019 level and was the highest monthly marketing total for any month since May 2019 and the highest March marketing total since 2000.

The current feedlot situation reflects the dynamics of the last year and suggests what to expect the rest of this year. Beginning in March 2020, the pandemic caused pronounced disruptions with direct impacts for several months and ripple effects that continue to today. The twelve months starting March 2020 had average monthly marketings and placements both decreased compared to the previous twelve months from March 2019 – February 2020. The average marketings were down slightly more than the decrease in placements in the previous twelve months and resulted in a rebuilding of feedlot inventories. The February 2021 on-feed total of 12.106 million head was the largest monthly feedlot inventory of any month since February 2006. While feedlot inventories dropped seasonally in March and April, it may be into the second half of the year before feedlot inventories drop cyclically below year earlier levels. The bottom line is that the pandemic effectively delayed progress in pulling down fed cattle numbers in 2020 and pushed more cattle into the first half of 2021.

In the context of the longer term cattle cycle, the pandemic impacts have extended the pipeline of cattle supplies and the time needed for cyclically tighter supplies to be expressed in cattle markets. The calf crop peaked in 2018, decreasing in 2019 and 2020, and should have resulted in significantly smaller feeder supplies by the end of 2020. However, estimated feeder supplies on January 1, 2021 were down a scant 0.2 percent year over year and total U.S. feedlot inventories started 2021 fractionally higher year over year.

Fed cattle prices have been disappointingly stagnant thus far in 2021, largely under the pressure of ample feedlot supplies. Fed cattle price improvement is expected in the second half of the year but progress has been slower than expected due to residual effects of pandemic disruptions and the February winter storm. Fed prices are expected to be higher year over year for the remainder of the year, mostly when compared to pandemic-reduced prices last year, but also due to improving fed cattle market fundamentals as the year progresses.

Benefits of Estrus Synchronization and Artificial Insemination

Mark Z. Johnson, Oklahoma State University Extension Beef Cattle Breeding Specialist

There are several benefits of estrus synchronization of beef cows. Regardless of when your calving season occurs, manipulating the reproductive process of your cow herd can result in shorter breeding and calving seasons. Accordingly, more calves born earlier in the calving season result in an older, heavier, more uniform calf crop when you wean. Shortened calving seasons permit improvements in herd health and management such as timing of vaccinations and practices that add to calf value with less labor requirements (or at the very least concentrating labor efforts into a shorter time frame). Cows that are closer to the same stage of gestation can also be fed and grouped accordingly which facilitates a higher level of management.

Estrus synchronization can be used for natural mating or breeding by artificial insemination (AI). Synchronization protocols permit us to concentrate the labor needed for heat detection to a few days, and in some cases eliminate the need for heat detection when cows can be bred on a timed basis.

Use of AI permits us to get more cows bred to genetically superior sires for traits of economic importance to our operation’s production and marketing goals. Synchronization at the onset of breeding season, results in more cows having heats in the first 18 – 25 days of breeding season. Female’s return heats will remain synchronized to a degree, which gives a second chance to AI each female in the early part of breeding season. Without any synchronization, herd managers are faced with a 21 days of continual estrus detection and typically only one opportunity for AI in most females.

Bottomline: estrus synchronization can be an important management tool to get cows settled as early in the breeding season as possible and get cows bred to bulls with highest possible genetic value. A defined breeding season is important to permit meaningful record keeping, timely management and profit potential. Maintaining a 60 to 75 day breeding and calving season can be one of the most important management tools for cow calf producers.

To view Dr. Johnson and Parker Henley’s discussion on Replacement Heifers & Breeding Schedules on Sunup TV Cow-Calf Corner from April 24, 2021.

To view a recent Rancher’s Thursday Lunchtime Series presentation on Synchronization and AI Tools by Dr. Jordan Thomas from University of Missouri.

Finishing Beef Calves On-Farm

Paul Beck, Oklahoma State University Extension Beef Cattle Nutrition Specialist

Rural landowners are often interested in raising livestock to slaughter for personal consumption, local marketing or for normal commodity markets. There are several options producers can use to finish cattle, ranging from finishing completely on forages to conventional drylot programs using high concentrate diets. Hybrid systems have been studied as an alternative to high-concentrate total mixed rations fed in confinement. These systems utilize the roughage supplied by pasture along with additional energy from supplemental concentrates. They may not meet the requirements to meet ‘grass-fed beef’ claims by the USDA, but do provide free-choice access to pasture.

An Alternative Finishing System

I conducted research with Jason Apple, a meat scientist currently at Texas A&M Kingsville, to compare conventional finishing at a High Plains feedyard to the hybrid ‘grain-on-grass’ system. In the first trial, calves from spring or fall calving herds were either sent to a Texas Panhandle feedyard for finishing as yearlings following a stocker program or kept at the home operation and supplemented with 1% of bodyweight per head per day with a grain/grain byproduct supplement until slaughter. Steers finished conventionally in confinement gained 4.4 lbs/day while steers fed concentrate supplement on pasture gained 2.5 lbs/day. Although the finishing period on pasture was 30 days longer on the average, steers finished in the conventional feedlot were 128 pounds heavier at slaughter and dressing percentage was higher 62.5% vs 60.6% for Conventional and Pasture, respectively). Conventionally finished cattle were 86% Choice while pasture finished were 78% Select quality grade.

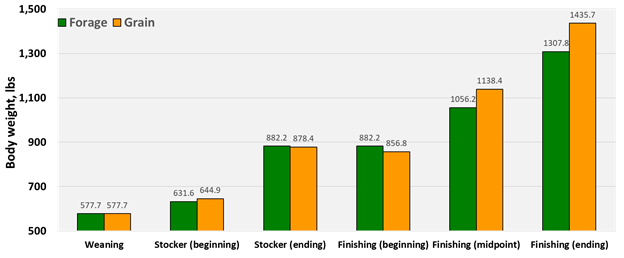

Figure 1. Effect of finishing on pasture (Forage) with 1% of bodyweight concentrate supplement daily or conventional finishing (Grain) on bodyweight of steers.

In the next trial, 60 calves were either finished in conventional Texas Panhandle feedyard or were kept on pasture with a grain/grain byproduct concentrate supplement fed at 1.5% of bodyweight daily. Steers finished on pasture with supplement gained 3.6 lbs per day (vs 4 lbs/day for conventional) and were fed 40 days longer than conventional steers, but were again still 40 pounds lighter at slaughter. But, hot carcass weights (836 for pasture vs 854 for conventional) were not as impacted as in the previous study, fat thickness was similar for the 2 treatments (0.62 inches for pasture vs 0.52 for conventionally finished) and dressing percentage was likewise similar (63% for pasture and 62.5% for conventional). In this experiment the cattle finished on pasture with supplement were 100% Choice with 73% being Premium Choice, while the Conventional steers were 93% Choice with 45% being Premium Choice. This research indicates that acceptable carcass performance can be obtained with limited energy supplementation on pasture.

Figure 2. Effect of finishing on pasture (Forage) with 1.5% of bodyweight concentrate supplement daily or conventional finishing (Grain) on carcass quality grade.

There are several items that producers should be aware of and be able to communicate to consumers if selling directly.

- The amount of retail cuts coming from a finished calf depends on the frame, muscling, skeletal structure, fat cover, and gut fill.

- The conversion of live animal depends on dressing percent (the amount of carcass per pound of shrunk live weight), in grain finished calves this ranges from 58% (usually dairy calves) to 66% (highly finished heavyweight beef steers), but in forage finished calves this can be much lower, usually due to gut fill and lower fat cover.

- A rule of thumb is on a well finished calf (0.6 inch of backfat at the 12th rib), you can expect red meat yield to be about 50% of the shrunk live weight of the animal (empty of gut fill).

- A tool to estimate red meat yield from a carcass is the Beef Cutout Calculator. The user must be aware that this is based on the average grain finished carcasses, and differences in finishing system will affect your results.

In summary, finishing cattle on farm can be an economical enterprise to add value to cattle. Finishing systems are not one size fits all and should be tailored to fit the producer’s production goals, target market, and management expertise. For more information about on-farm finishing programs look at our new Fact Sheet AFS-3303 Finishing Beef Cattle On the Farm.