Woodborers

Introduction

The term “woodborer” refers to the larval stage of some beetles and moths that feed inside stems, branches, or trunks of woody plants. For example, roundheaded and flatheaded borers are larvae of longhorned beetles and metallic wood-boring beetles, respectively. The lilac borer, the lesser and greater peachtree borers and the carpenterworm are caterpillars of wood-boring moths. Woodborers may feed in terminal shoots or burrow beneath bark or deep within heartwood. A few insect borers will attack (and kill) healthy trees, but most occur in trees that are stressed or weakened from transplant shock, drought, defoliation, poor soil conditions, age, poor adaptation or other causes.

Nearly all shade trees are subject to woodborer attack, but life cycles and habits vary with each insect species. Severe infestations can result in decline and death of young trees. Generally, the presence of woodborers is indicated by emergence holes created by adults as they chew through the bark. These holes vary in size and shape, depending on species, and are often located at the base of the tree or in crevices in the bark. Other signs of woodborer infestation include gummy exudate (ooze), dead areas under the bark that may or may not contain a larval gallery, or small piles of sawdust. Woodborers that feed under the bark frequently girdle the trunk, potentially killing the tree when infestations are severe. Those that tunnel in the heartwood increase the tree’s vulnerability to wood-rotting organisms and wind damage.

Trees are most susceptible to attack during the first year after transplanting, during an extended drought or outbreak of defoliating insects, or if disturbed by construction. Upon entering the cambium, sapwood or heartwood, woodborers are protected from many natural enemies, adverse weather conditions, and most control efforts. They often remain concealed until it is too late to save affected trees. Some management tactics apply universally to all plants and species of woodboring insects, whereas others are very specific. Vigorously growing trees are less attractive to woodborers, so practices that encourage rapid establishment and healthy growth will discourage woodborer infestations. Effective practices to prevent woodborer infestations include the following:

- Protect trunks of young or transplanted trees from egg-laying females with trunk wrap, burlap, aluminum foil or newspaper. Spray trunks with a properly labeled insecticide before wrapping, and then wrap the tree during fall leaf drop. Keep the wrap on the trunk until full leaf expansion in the spring, then remove, spray and rewrap the following fall. Do not let ties bind and girdle the trunk.

- Stimulate vigorous growth with proper fertilization and watering (refer to Extension Fact Sheet HLA-6412, Fertilizing Shade and Ornamental Trees).

- Prune out all dead and dying branches (refer to Extension Fact Sheet HLA-6409, Pruning Ornamental Trees and Shrubs).

- Select trees and shrubs that are locally adapted (e.g., Oklahoma Proven! website, https://extension.okstate.edu/programs/oklahoma-proven/index.html) and, preferably, less susceptible to woodborer attack. Ash, birch, cottonwood, locust, soft maple, flowering stone fruits (e.g., peaches and plums), willow and poplar are especially susceptible to woodborers. In Oklahoma, the predominant shade tree borers include flatheaded borers, roundheaded borers and clearwing borers.

Flatheaded Borers

Adult flatheaded borers are called metallic wood-boring beetles because of their iridescent, metallic luster. These beetles are boat shaped, generally metallic and colorful, and range from 1/3 inch to 1 inch in length. Larvae are 1/4 inch to 2 inches long, yellowish white and legless with a pronounced, flattened enlargement of the body just behind the head. This enlargement bears a hard plate on both the upper and lower surfaces (Figure 1). Flatheaded borers are especially injurious to established or mature shade and ornamental trees. They typically attack the sunny side of the tree (south and west). As they feed, they produce a shallow, long, winding gallery beneath the bark. The entire gallery may appear serpentine, sometimes referred to as “S” shaped. Flatheaded borers can sometimes damage or kill a tree by girdling it, cutting off the flow of nutrients through the phloem and, occasionally, water through the xylem. The life cycle of most flatheaded borers usually takes one or two years, but some species have been known to develop within wood for 25 years or more.

Figure 1. Flatheaded borer. (Photo by Gerald J. Lenhard, Louisiana State University, Bugwood.org)

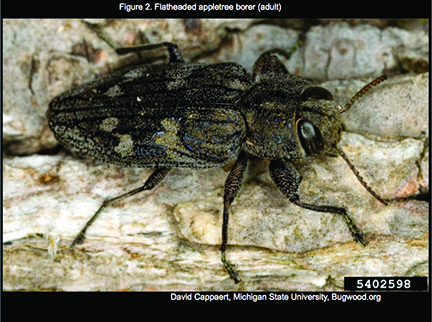

Flatheaded Appletree Borer

(Chrysobothris femorata)

Description: The adult beetle is boat shaped, dark greenish-bronze, somewhat iridescent and measures 1/2 inch long (Figure 2). The fully grown larva is whitish-yellow, legless, somewhat flattened and measures 1/2 inch to 1 inch in length. The head is barely visible from above as it is partly retracted into a large, swollen thoracic segment.

Figure 2. Flatheaded appletree borer (adult). (Photo by David Cappaert, Michigan State University, Bugwood.org)

Hosts: Flatheaded appletree borer attacks a wide range of deciduous trees, especially fruit, forest and shade trees and shrubs. It commonly feeds on maples and apple trees.

Life History: Adult beetles are active throughout the summer, mating and feeding on tender bark in tree crotches or around bud scars. They lay eggs in cracks and crevices in the bark. Eggs hatch about a week after being laid. The tiny larva enters the tree by chewing through the part of the egg that is in contact with the wood. Newly hatched larvae feed on living tissue in and surrounding the cambium layer. When fully grown, larvae cut deep into sapwood and heartwood, turn their tunnels at right angles either upwards or downwards, and form a cell in preparation for overwintering. In spring, larvae pupate without further feeding. From early May through July, adults emerge by chewing directly through the bark. Adult beetles are present on trees from early May to September or later depending on weather. This species exhibits one generation per year.

Damage: Flatheaded appletree borer causes substantial damage to ornamental plantings, nursery stock and a wide variety of fruit and shade trees across Oklahoma. Each year they kill scores of recently transplanted shade, pecan and fruit trees. Furthermore, they sometimes attack and kill large, well-established trees if under drought or other stress. Infestations are most common on the south and west sides of the trunk. Infested trees look unthrifty, producing scant foliage with branch dieback and dead, sometimes greasy areas in the bark of the main trunk or larger branches. Other symptoms of infestation include small, oval holes where beetles have emerged, scars where heartwood or sapwood is showing, bark growing over part of the dead area, or loosened bark. Larvae create irregular, winding tunnels underneath the bark of the host tree that are packed full of sawdust-like excrement (frass).

Management: Flatheaded appletree borer infestations can be minimized by maintaining tree vigor, wrapping trunks of new transplants with high-grade wrapping paper or burlap, and shading the south side of newly planted trees. Dead branches and trees, particularly those that have been dead for one to two years, should be removed before May 1 because they are sources of woodborers that have not yet emerged. Do not top or dehorn trees because this leaves dead wood that is an attractive breeding place for woodborers. Protect weak and young trees by spraying trunks and larger limbs at about three-week intervals during the early summer (for chemical suggestions, refer to Extension Fact Sheet EPP-7306, Ornamental and Lawn Pest Control for Homeowners).

Bronze Birch Borer

(Agrilus anxius)

Description: The adult beetle is elongated, somewhat flattened and measures 1/4 inch to 1/2 inch long. The body is olive black and iridescent with a copper-toned sheen (Figure 3). The larva is creamy white, legless, flattened and ribbon- like, and measures 3/4 inch to 1 1/4 inches long. The enlarged, swollen segment just behind the head is slightly wider than the rest of the body.

Figure 3. Bronze birch borer (adult). (Photo by Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org)

Hosts: Bronze birch borer attacks birch (Betula spp.), especially European white birch and Asian birch species. Native birches are also susceptible if they are weakened or under stress.

Life History: Adults emerge in late May through early June, feeding on leaves for up to two weeks while eggs mature. Eggs are laid in bark cracks and crevices, or other protected surfaces on the bark, with females preferring to oviposit on the sunny side of the trunk. Small branches in the upper crown are attacked initially, but larger branches and the lower trunk are attacked during subsequent infestations. Eggs hatch in about two weeks and newly emerged larvae tunnel into the cambium layer to feed. Larval galleries are packed with frass and appear serpentine. Larvae feed primarily in the cambial layer, but occasionally scar the xylem. Fully developed larvae overwinter within their serpentine feeding galleries and pupate the following spring. Adults emerge by chewing a “D”-shaped emergence hole through the outer bark. There is one generation per year in Oklahoma, although some individuals may require two years to complete development.

Damage: Non-native birches are especially susceptible to attack from bronze birch borer, although native species such as river birch can succumb to this beetle when suffering from drought, sunscald, root compaction and defoliation. Larvae girdle the tree as they tunnel through the cambium layer below the bark. Feeding galleries are often outlined by raised bumps on the outer surface of the bark, especially on the trunk. An early symptom of attack is canopy thinning resulting from girdling of small branches and limbs. Without treatment, girdling progresses to the point where the tree suffers from massive dieback and eventual mortality.

Management: The first line of defense is to plant resistant birches in proper sites in the landscape. Choose native, locally adapted birch species. River birch (Betula nigra) is an eastern Oklahoma native that prefers moist soils and does well in zones 4 through 9. Even native species are susceptible to bronze birch borer under stressful conditions, so keep trees healthy with adequate water and fertilizer. If insecticides are needed, trunks and limbs can be protected with sprays targeting egg-laying adults and hatching larvae. For lightly infested trees, systemic insecticides can be applied via trunk injection or soil drenches at the base of the trunk. Systemic insecticides should be applied preventatively in the early spring when the tree comes out of dormancy, or in the early fall to target the subsequent generation of borers (for chemical suggestions, refer to Extension Fact Sheet EPP-7306, Ornamental and Lawn Pest Control for Homeowners).

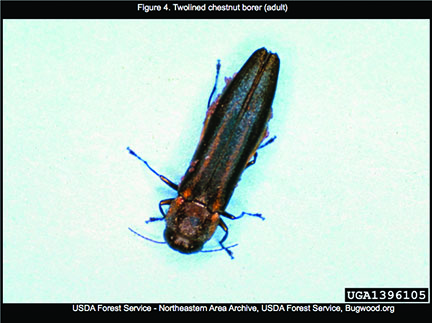

Twolined Chestnut Borer

(Agrilus bilineatus)

Description: Adults are similar in size and shape to those of bronze birch borer, except twolined chestnut borer is bluish black with a pale, somewhat indistinct line running along each wing cover (Figure 4). Larvae are also of similar appearance to bronze birch borer larvae; both species can be distinguished by the host tree in which they are found (i.e., twolined chestnut borer does not attack birch trees).

Figure 4. Twolined chestnut borer (adult). (Photo by USDA Forest Service – Northeastern Area Archive, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org)

Hosts: Oaks and chestnuts are hosts of twolined chestnut borer, and white, red, post and burr oaks are among the most preferred hosts.

Life History: Adults emerge from host trees April through September, depending on temperature and climatic conditions. Upon emergence, they feed on leaves of hosts and other hardwoods, mate and lay eggs. Eggs are laid in bark cracks and crevices and larvae hatch one week to two weeks later. Like bronze birch borer, females prefer laying eggs on sunny sides of trees and attack the upper crown first. Larvae of twolined chestnut borer tunnel below the bark and feed on the cambium, occasionally scarring the xylem. Mature larvae overwinter in the tree and pupate in the spring. Adults emerge by chewing a ”D”-shaped emergence hole in the outer bark. There is one generation per year in Oklahoma, although some individuals may require two years to complete development.

Damage: Feeding by twolined chestnut borer results in damage similar to that of bronze birch borer. Branch dieback, canopy thinning and loss of tree vigor are common symptoms. When infestations are severe, girdling of the limbs and main trunk eventually kill the tree. Other signs and symptoms of attack include loose bark covering frass-packed galleries and the presence of ”D”-shaped emergence holes in the bark.

Management: Like other native woodborers, twolined chestnut borer commonly attacks weakened or stressed trees. Therefore, keep trees well watered, fertilized and stress-free to prevent attacks. If insecticides are needed, trunks and limbs can be protected with sprays targeting egg-laying adults and hatching larvae. For lightly infested trees, systemic insecticides can be applied via trunk injection or soil drenches at the base of the trunk. Systemic insecticides should be applied preventatively in the early spring when the tree comes out of dormancy, or in the early fall to target the subsequent generation of borers (for chemical suggestions, refer to Extension Fact Sheet EPP-7306, Ornamental and Lawn Pest Control for Homeowners).

Roundheaded Borers

Adult roundheaded borers are called longhorned beetles because of their long antennae. These beetles range from less than 1/4 inch to more than 3 inches long. They are cylindrical or straight-sided, hard-shelled, and often beautifully banded, spotted or striped with contrasting colors. Larvae are white to yellowish, rather round bodied with distinct segmentation, and have a circular enlargement behind the head with a hard plate on the upper side (Figure 5). Most have small legs, but some are legless. Many species feed beneath the bark briefly before entering the sapwood and heartwood, while others never tunnel deep into the tree. Larval galleries are packed with borings arranged in concentric layers, so that arc-like bands appear when galleries are exposed. Roundheaded borers commonly burrow in heartwood, making tunnels as large or larger than a pencil (Figure 6). Larvae produce coarse, sawdust-like frass, which is often observed around the base of the tree. Generally, roundheaded borers are more numerous and more destructive than flatheaded borers. Some important members of this destructive group are the redheaded ash borer, cottonwood borer, locust borer, elm borer, poplar borer and painted hickory borer.

Figure 5. Roundheaded borer. (Photo by Gerald J. Lenhard, Louisiana State University, Bugwood.org)

Figure 6. Cottonwood infested by poplar borer. Notice galleries containing larvae and pupae. (Photo by Gerald J. Lenhard, Louisiana State University, Bugwood.org)

Locust Borer

(Megacyllene robiniae)

Description: The adult beetle is jet black with bright yellow bands crossing the thorax and “W”-shaped markings on the wing covers (elytra). They measure about 3/4 inch in length and have antennae almost as long as the body (Figure 7). Larvae measure about 1 inch when fully grown and are plump, legless and creamy white with a brown head.

Figure 7. Locust borer (adult). (Photo by Clemson University – USDA Cooperative Extension Slide Series, Bugwood.org)

Hosts: The locust borer is a very destructive pest of black locust.

Life History: Adults are quite numerous in late summer through September and frequently feed on flowers of goldenrods during morning hours. Later in the day, they can be seen running up and down the trunks of black locust trees in search of egg-laying (oviposition) sites. Eggs are deposited in cracks in the bark of trees. Newly hatched larvae bore into the inner bark and construct small cells just beneath the outer corky layer. Larvae overwinter in these cells and resume feeding in the spring when leaf buds of the host tree begin to swell. They tunnel deep into heartwood and feed until reaching maturity in mid- to late July. There is one generation per year.

Damage: Larvae develop in trunks of host trees, tunneling deep into heartwood, causing the tree to be structurally unsound. One of the first signs of locust borer attack may be the presence of brownish sawdust and wet spots on the bark (late summer). Later in the season these spots become filled with a wet, yellowish sawdust and gummy exudate. Stressed and/or young trees less than 7 inches in diameter are more likely to be attacked.

Management: Black locust should not be planted as a shade tree in areas where this woodborer is a problem. When planted in woodlots, stands should be mixed with other species. Old trees that have been topped should be removed because they can become a source of these beetles. Locust groves should not be grazed because grazing stresses shallow-rooted trees, which in turn become a more attractive target for the beetle. Some protection may be obtained by thoroughly spraying tree trunks with a registered insecticide from late August through the end of September, which kills adults during oviposition (for chemical suggestions, refer to Extension Fact Sheet EPP-7306, Ornamental and Lawn Pest Control for Homeowners).

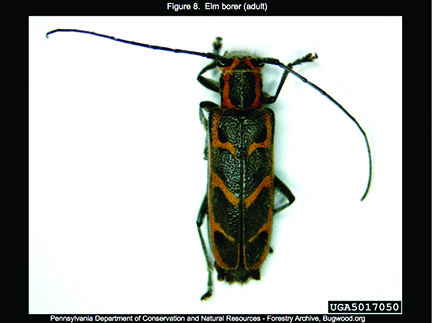

Elm Borer

(Saperda tridentata)

Description: Adult beetles measure 3/8 inch to 1/2 inch long with a grayish body that has three orange-red, transverse lines across each wing cover and twin black spots on the thorax (Figure 8). Full-grown larvae measure 1/2 inch long and are robust, legless and cream colored with a brown head.

Figure 8. Elm borer (adult). (Photo by Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources – Foresty Archive, Bugwood.org)

Hosts: The elm borer attacks dead or weakened American and slippery elms.

Life History: Elm borers are more common in cities where elms are subjected to adverse growing conditions. Adults are present from late April through late July and feed on elm leaves and petioles. Eggs are deposited in small holes chewed in bark crevices, often on freshly cut logs or weakened trees. Larvae bore beneath the bark, filling the mines with fibrous frass and completely destroying the phloem and cambium. At maturity, they bore into the sapwood, construct cells for pupation, and overwinter. There is one generation per year.

Damage: Signs and symptoms of an elm borer infestation include canopy thinning, yellowing foliage, dead limbs scattered around the tree, and sawdust-like frass extruding from bark crevices. These woodborers can also transmit Dutch elm disease from infected to healthy elms.

Management: Infested branches and trees should be removed and burned before May 1. Remember, dehorning and other poor pruning practices encourage woodborers (for pruning suggestions, see Extension Fact Sheet HLA-6409, Pruning Ornamental Trees, Shrubs and Vines).

Cottonwood Borer

(Plectrodera scalator)

Description: Adult cottonwood borers are conspicuously colored black and white beetles that measure 1 1/4 inches to 1 1/2 inches in length (Figure 9). Larvae are large, white, deeply segmented and reach 1 3/4 inches to 2 inches long when fully grown.

Figure 9. Cottonwood borer (adult). (Photo by Charles T. Bryson, USDA Agricultural Research Service, Bugwood.org)

Hosts: The cottonwood borer attacks cottonwood, poplar and willow trees.

Life History: Adult beetles may be found late May through August feeding on tender, young shoots. Eggs are deposited at or a little below ground level in holes chewed in the bark by the female. Considerable injury may be done in this way to young cottonwood and willow trees. Upon hatching, young borers work into the tender bark just outside the wood and penetrate downward into large roots as cold weather approaches. After the second winter, larger larvae occupy large tunnels at the base of the tree. Pupation occurs the second season. Thus, this woodborer needs two years to complete its development.

Damage: The cottonwood borer attacks trees mostly at or below ground level and may completely girdle the trunk, killing the tree. During severe infestations, smaller trees may become weakened and break during high winds and storms.

Management: If ornamental plantings become infested, small larvae can be cut out from the base. Alternatively, a properly labeled insecticide may be injected into the tree by a certified arborist or other tree care professional.

Wood-Boring Caterpillars

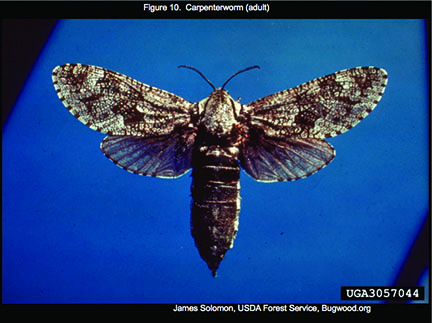

Carpenterworm

(Prionoxystus robiniae)

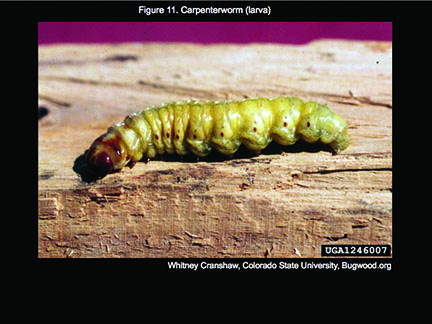

Description: The adult is a large moth with a mottled gray body and wings (Figure 10). The larva is a large, greenish-white caterpillar with a dark head that measures 2 inches to 3 inches long when mature (Figure 11).

Figure 10. Carpenterworm (adult). (Photo by James Lolomon, USDA Forst Service, Bugwood.org)

Figure 11. Carpenterworm (larva). (Photo by Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org)

Hosts: Carpenterworms attack a wide range of hardwood trees, especially oaks, elms, ashes, and poplars. They may also be found in black locust, willows, boxelder, cottonwood and fruit trees such as pear and cherry.

Life History: Adult moths appear in late spring and early summer. Females deposit eggs in wounds or cracks in the bark. Larvae hatch and begin to feed in the inner bark during the first season. In the second summer, they tunnel into sapwood or heartwood and feed until reaching the center of the tree. Development may take two to three years to complete.

Damage: Carpenterworms make large tunnels throughout the heartwood of trunks and limbs. Heavily infested trees are prone to breaking in high winds. Outward signs of injury are damp, dark-colored sawdust and frass, which may be especially noticeable in cracks and crevices as the dead bark shrinks. Frass may also pile up at the base of the tree. Dead bark may peel off, revealing the work of younger larvae in the sapwood.

Management: Control is difficult in natural stands. Heavily infested trees can be removed and stands can be thinned to promote more vigorous growth and resistance to carpenterworm. Heavily infested trees should be removed and burned in the spring before moths emerge. The remaining stumps should be dug out and burned, since they may harbor woodboring larvae below the soil line. During warm days in spring, susceptible trees can be sprayed with registered insecticides on the trunk and branches (for chemical suggestions, refer to Extension Fact Sheet EPP-7306, Ornamental and Lawn Pest Control for Homeowners).

Lilac/Ash Borer

(Podosesia syringae)

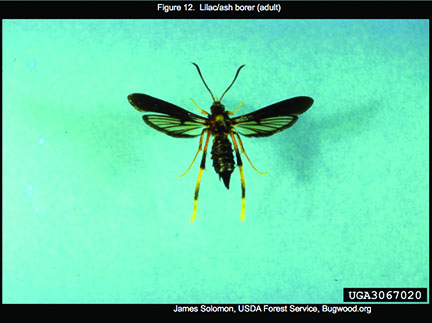

Description: Adult lilac borers, also known as ash borers, are brown and black clearwing moths that strongly resemble paper wasps (Figure 12). They are active during the day and mimic wasps for protection from their own natural enemies. Larvae are creamy white, wormlike and have a small, brown head (Figure 13). Prolegs on the abdomen are greatly reduced, much smaller than those of typical caterpillars.

Figure 12. Lilac/Ash borer (adult). (Photo by James Solormon, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org)

Figure 13. Lilac/Ash borer (larva). (Photo by David Cappaert, Michigan State University, Bugwood.org)

Hosts: Lilac/ash borer attacks green and white ash, lilac and privet.

Life History: Adults emerge in May from infested trees and shrubs. Old pupal skins are often seen sticking out of emergence holes until they degrade. Upon mating, females lay eggs on the lower portions of canes and stems. Larvae hatch and bore under the bark, feed on phloem and cambium tissue, and may tunnel as deep as 2 inches into the trunk. Winter is spent as partially mature larvae, which continue feeding in spring until pupating just below the bark surface. There is one generation per year. A closely related species, the banded ash clearwing (Podosesia aureocincta), resembles lilac/ash borer except it has two light bands on the abdomen. Banded ash clearwing attacks similar hosts, but emerges and lays eggs in late summer to early fall.

Damage: Infested trees may have gnarled swellings at the attack sites, and often have increased sucker growth. Typically, injuries are concentrated on the lower 12 feet of the trunk. Larvae can girdle small branches and canes, causing dieback. Frass produced by larvae is excreted from galleries, resulting in piles of sawdust-like material at the base of the tree.

Management: Severely infested canes should be cut at soil level and destroyed in early spring. Uninfested canes can be sprayed with a registered insecticide in early May, repeating the application two or three times at two- to three-week intervals. Pheromone traps are commercially available to aid in monitoring and correct timing of insecticide applications (for chemical suggestions, refer to Extension Fact Sheet EPP-7306, Ornamental and Lawn Pest Control for Homeowners).

Bird Damage

Sapsuckers, a close relative of woodpeckers, cause damage to trees that is often attributed to wood-boring insects. These birds visit a tree many times, feeding on sap that accumulates in the holes they have drilled. Sapsucker damage appears as rows of holes circling or running vertically on the trunk or larger limbs of the tree (Figure 14). This contrasts with woodborer emergence holes, which occur in a random pattern on the trunk or limbs. Contrary to popular belief, sapsuckers rarely, if ever, dig through bark to capture wood-boring insects. Rather, they feed on the cambium and sap in the phloem.

In Oklahoma, the yellow-bellied sapsucker is the most common species that damages trees. They winter in the South and spend the summer in the northern United States. Thus, they often cause damage during their migrations in the spring through early summer, and again in fall in Oklahoma. Tree species most commonly attacked by sapsuckers are pine, sugar maple, birch, willow, magnolia, apple and pecan.

Figure 14. Yellow-bellied sapsucker damage. (Photo by Chazz Hesselein, Alabama Cooperative Extension System, Bugwood.org)

Woodborers from Firewood

Occasionally, woodborer adults emerge from infested firewood that is stored or brought indoors during the winter. These insects entered the wood when it was a standing tree or when freshly cut and stored outdoors during the spring. When an infested piece of wood is brought inside, warm room temperatures stimulate development and emergence of adults. Most of these insects are harmless because they attack only unseasoned wood. A common woodborer seen in Oklahoma is the redheaded ash borer (Figure 15). This species infests newly cut, or unseasoned ash, oak, hickory, persimmon and hackberry. These pests are a nuisance, but will seldom, if ever, damage any structural timbers or household goods or re-infest wood inside the home. For specific information on chemical control of woodborers, refer to Extension Fact Sheet EPP-7306, Ornamental and Lawn Pest Control for Homeowners.

Figure 15. Redheaded ash borer (adult). (Photo by Gyorgy Csoka, Hungary Forest Research Institute,

Bugwood.org)

Eric Rebek

Extension Entomologist