Raised Bed Gardening

Raised bed gardens are an ideal way to grow vegetables and small fruit. They are elevated a few inches or more above the soil level, and just wide enough to reach across by hand. Plants can be grouped together in a bed with permanent walkways on either side. The soil does not get compacted, since the soil in which plants are grown is never walked on.

The idea of growing plants in single file or “row crops,” started with the use of a horse and plow to cultivate crops on a large scale. The straight rows, far enough apart to drive a horse between, made plowing easier. Wider spaces later accommodated tractors and their implements. Not knowing the reasons behind growing crops in rows, many home gardeners plant single row vegetable gardens. However, foot traffic on each side of a single row can severely compact soil by the end of a growing season. The excessive row spacing also wastes garden space that can be planted with crops.

Raised bed gardens can range from a simple rectangular plateau of soil to a more elaborate bed framed in wood, stone and mortar, straw bales or modern snap-together plastic blocks. Although more expensive and time consuming to build, permanent structures will keep soil in place during heavy rains and will look nicer in the landscape. However, for a large garden, several beds of mounded soil are very adequate to achieve desired results. Just make sure plenty of mulch is used on the soil to hold it in place during drenching rains.

Benefits of Raised Beds

Higher Yields. Raised beds allow more garden space for growing plants, with less space utilized for walking paths. Individual plant yields may be slightly less with less space per plant than in traditional rows, but more plants can be grown in a given space.

Better Soil. Amendments such as compost and fertilizer are only spread on beds and not wasted on pathways. Looser (non-compacted) soil also drains better. Frequent tillage of the garden can be elimination.

Water Conservation. Plants grown close together shade the soil, decrease evaporation and keep roots cooler. Water is only provided to the beds and not the pathways.

Fewer Weeds. Closely planted crops keep weeds crowded out. Pathways can be covered in landscape fabric or mulch to choke out weeds.

Extended Season. Soil in raised beds can be worked earlier in the season, because it warms up faster than soil in traditional in-ground gardens. Rainy weather is less of a hindrance to working in the garden, since mud is not an issue.

Better Pest Control. Raised bed gardens are easy to cover with insect screening fabric. Crops are easy to rotate from bed to bed — preventing a buildup of pests.

Raised Bed Dimensions

Raised beds can be made into any shape desired. The maximum recommended width of a raised bed is about four feet, since the average adult can reach about two feet into the garden from each side. This prevents the need to step into the raised bed. (If making a children’s garden, take shorter arms into consideration.) The length of a raised bed varies considerably. If up against a fence, some raised beds go the length of a fence. Some hug three sides of a backyard. Those in the middle of backyards tend to be shorter — eight feet long is an average length. In schoolyards, beds are designed so that many children can work at once.

Height of the bed can vary greatly. A six-inch increase in height above the existing soil grade will greatly enhance drainage. However, beds can be constructed 18 inches to 24 inches tall or higher to accommodate gardeners who like to sit while gardening. Wide boards placed at the top of the bed’s sides and supported like a shelf, or wide bed materials (cinder blocks, treated timbers, etc.) provide a place for taking a break and a way to garden without stooping. Some raised beds and elevated beds are tall enough that gardeners can garden while standing or those in wheelchairs. Raised bed gardening helps make gardening accessible for everyone.

Planning the Layout of Raised Beds

For best light exposure, plan to build beds in a north/south orientation (plant taller plants on the north side of shorter plants to avoid shading smaller plants). Paths between beds should be wide enough to comfortably walk, push a wheelbarrow, and haul vegetables. Make a rough sketch of backyard dimensions before staking out the gardens. If space is limited, make a scale sketch on graph paper. With a separate piece of paper, cut rectangles the size of the proposed beds and arrange them on the sketch to fit in the most efficient manner.

Make a list of crops to be grown. This will help determine how much space is required. Many gardeners like to work their vegetable plantings into the landscape. Beds do not have to be aligned. They can be located around the perimeter of the yard to allow space for play areas or entertaining. When growing crops that sprawl, such as squash or watermelon, put them in a bed by themselves. This will keep them from covering other crops.

The final step in planning is to stake out the beds and walk through them to make sure it is a workable arrangement before expending labor.

Building a Raised Bed Garden

To make an unframed raised bed, the following tools will be needed: shovel, garden spade, spading fork, rake, string, four stakes and a tape measure.

Before building a raised bed, eliminate all weeds and turf from the area. Bermudagrass lawns will have to be killed through solarization (smothered with black plastic for several weeks) or with a glyphosate-containing herbicide. Either method must be done when grass is actively growing. Late summer is the best time to do this, since high temperatures will make either method more effective.

Outline the corners of the bed with stakes and stretch twine tight between them. If making a simple mound-type bed, dig around the edge of the twine with a sharp spade. This will neatly define the edge of the bed and make a furrow for drainage. Use a steel rake to pull soil up around the edges of the bed. Use the back side of the rake to flatten out the top. A hiller-furrower attachment on a rototiller can also shape beds as described (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Bed preparation

Beds can be initially cultivated with a tiller, then finished with hand tools. Beds adjacent to a bermudagrass lawn will need a barrier in place, or grass will invade the bed within one month after construction. A barrier material should be buried one foot deep and extend 3 inches to 4 inches above the soil line to keep grass out. As with any vegetable garden, the perimeter area must be kept weed and grass free to keep beds clean.

Double digging beds can be very beneficial, especially in tight clay soils. Spade the loose, top layer of soil to one side of the bed. Use a spading fork to pierce and loosen deeper soil layers before returning the top layer to its place. This allows for greater aeration and water penetration (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Double Digging (top, Spade Top Soil; bottom, Spading Fork Loosens Deeper Soil Layers.)

While turning soil, work plenty of organic materials into the bed. Compost, rotted grass clippings, manure, etc., helps keep soils aerated and less compacted, while increasing its water and nutrient retention capacity. Be sure to remove any clumps of weedy grasses and rocks while working the soil.

Some soils are not suitable for gardening, such as heavy clay soils. A good sandy loam soil or bagged top soil may need to be added to fill beds.

Oklahoma’s high temperatures rapidly decompose organic matter. Plan to add a two-inch layer of compost or other organic materials every spring and fall. This should replenish the organic matter needed in Oklahoma’s soils.

When the bed is finished, leave stakes in place to guide water hoses around corners. Old pieces of pipe slipped over stakes will help garden hoses roll around the corners.

If constructing a framed bed, level the area, make the basic frame, then prepare the soil in the bed, adding additional soil from pathways. Additional soil and compost materials may need to be added to fill it to the top. A raised bed filled with alternating layers of compost and soil will make an ideal environment for plant growth.

Framed-in beds can be made with treated lumber, treated landscape timbers, concrete blocks, rock or bricks, and many recycled materials. Use of railroad ties is not recommended, unless they are well aged — creosote vapors can burn tender plants. While pressure treated wood available for consumers does not contain the toxic chemicals as it once did, use caution when sawing or drilling. Also use protective clothing like dust masks and unlined rubber gloves when working with treated lumber. Avoid breathing sawdust. If cost is no object, heart cedar or redwood can be used, but will still rot more quickly than treated lumber when in contact with soil.

Soil will expand and contract when freezing and thawing. Wood can easily “bow-out” and masonry may crack. Reinforcing rods used in all of these materials will help give structural stability (see Figure 3 for a simple landscape timber bed held together with reinforcing rods).

Figure 3. Simple Landscaped Timber Raised Bed (top, Overlap Timbers; bottom, Reinforcing Rods Hold Timbers Together.

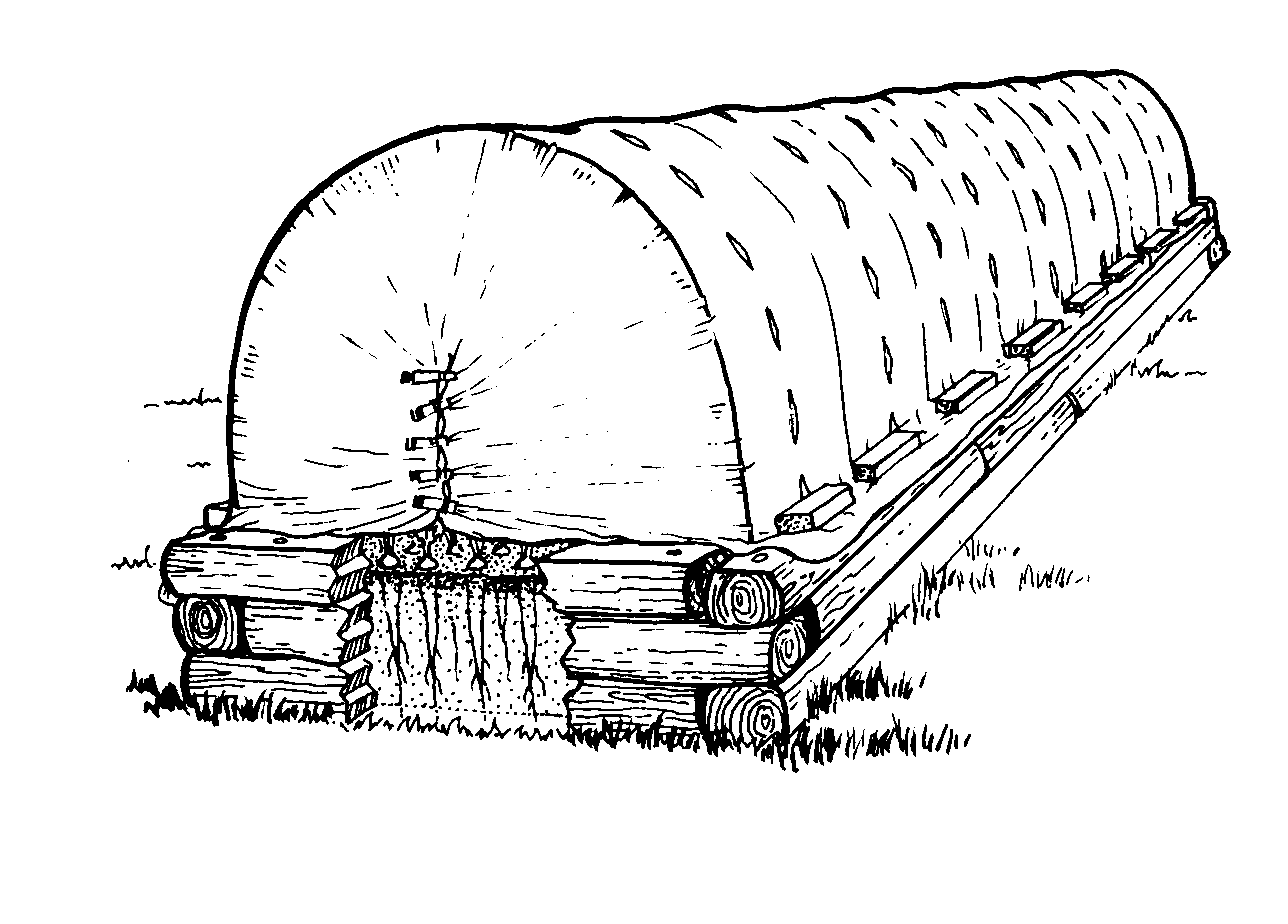

To make raised beds useable throughout the year, consider using flexible black plastic pipe or No. 9 gauge wire hoops down the length of the row and stretching plastic over them to extend the season. The plastic can be secured along the edges using bricks or boards. To create ventilation, use slit plastic or have two edges meet over the top and secure them with clothespins. These can be opened on warm and sunny days (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Raised Bed Garden Row Cover.

Gardening with Raised Beds

Plantings can be alternated in a zig-zag pattern down the row to fit more plants into the bed. Intercropping fast-maturing plants with longer-season crops will optimize the use of space.

Although more plants shade the soil and reduce evaporation, the higher plant population may need more water. Unframed raised beds can lose moisture along the side unless they are heavily mulched. They do have the advantage of warming up more quickly than flat soil surfaces in the cooler seasons.

Overhead sprinklers that broadcast water will also water the rows in-between and encourage weed growth. It is better to use drip irrigation in each bed. Small gardens can be easily hand-watered using a hose wand with a sprinkler head to keep droplets small.

The great advantage to raised beds is that fertilizer is used only on the soil where plants grow. None is wasted on pathways. Take a soil test first. Fall is the best time. If soil pH needs adjusting or slow-acting materials such as phosphorus or potassium need to be added, they can be worked into the soil before the rush of spring planting.

Plants in raised beds are more crowded and nutrients can be depleted in a shorter time than in conventional gardens. Be sure to sidedress heavy feeders such as onions, tomatoes and cole crops before they flower or begin bearing.

Many gardeners who know the value of crop rotation and maintenance of soil fertility will rotate 25 percent of their bed space into cover crop each year. Use of cool-season legumes such as hairy vetch or Austrian winter peas help replenish organic matter to beds each winter. In the summer, use buckwheat or cowpeas in beds that are in rotation.

In crowded raised bed plantings, insects and diseases can build up quickly. A brief walk through the garden each day to check for signs of infestation can help stop a problem before it gets serious. Keep dense-growing plants, such as tomatoes, trained to keep off the ground. Pinch off the first two suckers to allow for air movement around the base of the plant. Check undersides of leaves for insect eggs and destroy them before they hatch. Be sure to rotate vegetables from similar families to avoid a buildup of pests in the soil. For example, tomatoes, peppers and eggplants should all be moved to a new location each year because they are related and share the same problems. For further details on insect identification and control, see Extension Fact Sheet EPP-7313, Home Garden Insect Control.

Selecting Vegetables for Raised Beds

No special varieties are needed for raised bed gardens; however, the more compact types will leave room for a larger harvest. Sprawling plants, such as melons and cucumbers will need plenty of space. Train them up on wire or string trellises or select bush-types. Just remember yields on bush-type plants will be lower.

Very tall plants, such as corn or okra can also be grown in raised beds. Plant them on the north side of the garden, so they will not shade other vegetables. Corn is a heavy nitrogen feeder. Plan to follow this crop with a nitrogen-rich legume, like snap beans, to make up for any extreme deficiencies.

Pole beans grow well in raised beds and can be intercropped with faster, shorter growing plants, such as lettuce, radishes and Chinese cabbage. Bush beans can be grown in a double-wide row for maximum production.

Tomatoes will need to be staked or caged. Choose disease-resistant varieties to reduce the need for spraying (see Extension Fact Sheet HLA-6012, Growing Tomatoes in the Home Garden).

Perennial crops such as asparagus, rhubarb, horseradish and some herbs should be planted in a separate garden. A few short-term annual vegetables can be tucked in among perennials while they are getting established.

Small fruit crops such as strawberries, blueberries, blackberries and raspberries are ideally suited to raised beds.

To plan spacing and planting dates for vegetables, see Extension Fact Sheet HLA-6004, Oklahoma Garden Planning Guide. With a raised bed garden, plants do not need space between rows for maintenance. So references on “between row” spacing does not apply. For example, if the Fact Sheet, or the back of a seed packet, recommends seeding beans four inches apart within the row and one and one-half feet apart between the rows, simply sow beans four inches apart in any direction in the raised bed.

Initial preparation of a raised bed can take many hours and hard work. However, in later years, simply turning over the top few inches and planting will be much easier than tilling and re-creating a large traditional garden every spring. The rewards for this labor will also come with healthier, more productive crops and less time spent weeding, leaving more time to enjoy planting and harvesting.

David A. Hillock

Extension Consumer Horticulturist

Shelley Mitchell

Assistant Extension Specialist