PACEs for Children: Overcoming Adversity and Building Resilience

- Jump To:

- Adversity in Oklahoma

- The Ten PACEs Include

- Ways Parents can Promote PACEs

- Provide Emotional Guidance

- Use Discipline, Not Punishment

- Provide Fair Rules and Limitations

- Create and Maintain Healthy Routines

- Promote Participation and Strong Relationships

- Additional Resources for Parents and Children

- References

Adversity in Oklahoma

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are events or conditions, such as childhood abuse, neglect, domestic violence and parent substance abuse, that occur before the age of 18. Oklahoma is one of the states with the highest number of children with ACEs. However, there are positive experiences that can reduce the effects of adversity and build resilience in children and teens.

What are Protective and Compensatory Experiences (PACEs)?

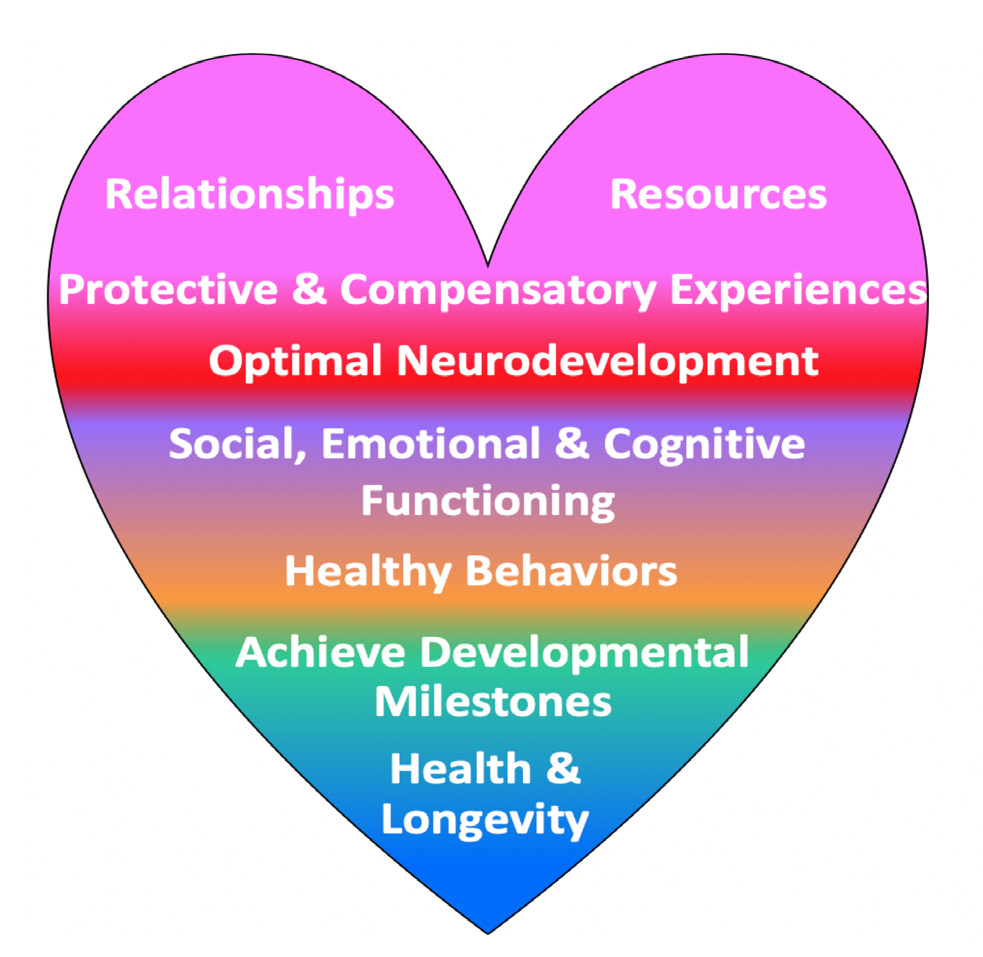

Protective and compensatory experiences (PACEs) are positive experiences that can increase resilience and protect against risk for mental and physical illness. In the PACEs Heart Model below, supportive relationships and resources make up PACEs. Adults who had many PACEs in their childhood have fewer problems related to health and wellbeing even if they had a history of ACEs.

The Ten PACEs Include

- parent/caregiver unconditional love

- spending time with a best friend

- volunteering or helping others

- being active in a social group

- having a mentor outside of the family

- living in a clean, safe home with enough food

- having opportunities to learn

- having a hobby

- being active or playing sports

- having routines and fair rules at home

Ways Parents can Promote PACEs

There are many ways you can promote PACEs for your children if they have experienced adversity. Below are some ways you can foster positive experiences.

Encourage Communication and Ask for Input

High-quality parent-child relationships are related to positive child outcomes. You can encourage open communication with your child by listening, sharing, asking open-ended questions and using “I” messages. “I” messages are a way of expressing your thoughts and feelings without placing blame on your child. It’s important to have fun conversations free from judgment or criticism. These types of talks can lead to greater disclosure when it’s time to talk about more serious issues. It is important to encourage communication with teens as they gain independence and make important decisions.

Provide Emotional Guidance

You can help your children understand and regulate their emotions by being an emotion coach. Emotion coaching involves helping children identify and label their emotions, responding with empathy and working to solve the problem together. Children with ACEs may have more difficulty regulating their emotions. You can use phrases such as: “It’s okay to feel this way.” or “I hear what you are saying, and I am here for you.” These statements show you understand and you’re willing to help solve the problem.

Use Discipline, Not Punishment

Children need to know there are consequences for their behavior. However, you should not use tactics like spanking, hitting, shouting or name-calling. In children with ACEs, these tactics can increase distress. Instead, you should clearly state the unwanted behavior, set reasonable consequences and give the child a chance to fix their mistake or apologize. Explain how the behavior affects other people but avoid embarrassing the child in front of other people.

Provide Fair Rules and Limitations

It is important to provide clear rules and limits for children. These should change as children get older. You can ask for your child’s input when it comes to setting fair rules. This can give the child a sense of control. Rules should be sensible and consistent. Remember to model the behaviors you expect from your children.

Create and Maintain Healthy Routines

Regular and healthy routines reduce stress. Eating together as a family, creating a bedtime and sharing in family activities are related to positive health. It is important that routines do not become boring or rigid. A reasonable amount of structure can be beneficial.

Promote Participation and Strong Relationships

Supportive relationships can increase social skills and decrease feelings of loneliness. Having a mentor outside of the family can increase success in school and lessen risky behaviors. Encourage children and teens to engage in activities like sports, clubs and community organizations. You can also provide ways for children to meet and spend time with people with different backgrounds. Diverse experiences and relationships can help shape a child’s identity.

Additional Resources for Parents and Children

- ACEs Connection

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network

- Administration for Children and Families Resource Guide to Trauma Informed Human Services

References

- ACEs Connection (2018) https://www.acesconnection.com

- Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Bremner, J. D., Walker, J. D., Whitfield, C., Perry, B. D. and Giles, W. H. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256(3), 174-186.

- Bethell, C. D., Davis, M. B., Gombojav, N., Stumbo, S., & Powers, K. (2017). Issue Brief: A national and across state profile on adverse childhood experiences among children and possibilities to heal and thrive. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

- Dozier, M., Bernard, K., & Roben, C. K. (2018). Attachment and biobehavioral catch-up. Handbook of attachment-based interventions, 27-49.

- Hays-Grudo, J. & Morris, A.S. (2020). Adverse and protective childhood experiences: A developmental perspective. Washington DC: APA Press.

- Hurd, N. M., & Sellers, R. M. (2013). Black adolescents’ relation-ships with natural mentors: Associations with academic engagement via social and emotional development. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 19(1), 76.

- Lu, W., & Xiao, Y. (2019). Adverse Childhood Experiences and Adolescent Mental Disorders: Protective Mechanisms of Family Functioning, Social Capital, and Civic Engagement. Health Behavior Research, 2(1), 3.

- Morris, A. S., Hays-Grudo, J., Treat, A. E., Williamson, A. C., Huffer, A., Roblyer, M. Z. and Staton, J. (2015). Assessing resilience using the protective and compensatory experiences survey (paces). Paper presented at the Society for Research in Child Development, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

- Munson, M. R., & McMillen, J. C. (2009). Natural mentoring and psychosocial outcomes among older youth transitioning from foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 31, 104-111. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.06.003.

- Resnick, M. D., Harris, L. J., & Blum, R. W. (1993). The impact of caring and connectedness on adolescent health and well-being. Journal of Pediatrics and Child Health, 29, S3-S9.

- Rubin, K. H., Bukowski, W. M., & Bowker, J. C. (2015). Children in peer groups. Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science, 1-48. Ungar, M. (Ed.). (2005). Handbook for working with children and youth: Pathways to resilience across cultures and contexts. Sage Publications.

Erin Ratliff

Graduate Student, Human Development and Family Science

Amanda Sheffield

Morris Regents Professor and Child Development Specialist

Jennifer Hays-Grudo

Regents Professor

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences