Oklahoma Economic Pulse Survey Results

- Jump To:

- Background

- Data Collection

- Results and Discussion

- Strength of Economy comparison

- Rural versus Urban Responses on Changes in Economic Strength

- Geographic Regional Differences in Responses on Economic Strength

- Anticipation of When the Worst Effects will be Over

- Comfort Level with Group Meetings

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1.

Novel coronavirus (COVID-19) has disrupted businesses and households across the world. Oklahoma residents participated in a survey on beliefs regarding COVID-19 economic and social recovery within the state and was conducted between May 14 and June 5, 2020. Respondents were divided by occupation and geographic areas to examine their views on local economy strength, expectation on when the worst impacts will have ended and comfort in group meetings.

Most respondents perceived their local economy was somewhat weak in contrast to January; however, rural respondents generally felt the economy had deteriorated less since January as compared to urban residents. Declines in economic strength in urban counties/districts aligned with other reports showing greater increases in unemployment and greater density of businesses perceived to be harder hit by the pandemic (e.g. restaurants and tourism) as compared to rural counties/districts. Forty-five percent of respondents felt the impacts of the crisis would not abate for one year or longer. In addition, 41% of all respondents were comfortable attending a meeting of more than 10 people at the time of the survey. Responses from rural areas were more likely to report being comfortable attending 10 or more person meetings. These results, combined with observations on economic impacts of COVID-19 in Oklahoma, will help the Oklahoma State University Extension, chambers of commerce and other agencies target information and education for economic recovery. It is important to note as the number and potential severity of cases change in and around the state, people’s perceptions of the impact of COVID-19 may change. These results should be considered a snapshot in time of the perceptions of COVID-19.

Background

On Jan. 30, 2020 the International Health Regulations Emergency Committee of the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 (caused by the virus SARS-CoV-2) a “public health emergency of international concern” (CDC, 2020). By Feb. 23, 2020 community spread of COVID-19 first became apparent in the U.S. (CDC, 2020). The first confirmed case of COVID-19 occurred in Oklahoma March 13, 2020, with the first death March 19, 2020 (New York Times, 2020). In an effort to stave off new cases, on March 24, 2020 Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt ordered all non-essential business to close for 21 days starting March 25, 2020 (News 9, 2020). This closing of businesses was extended until April 22, 2020 when governor Stitt announced the “Open Up and Recover Safely Plan,” which allowed for phased reopening based on “scientific modeling from public health experts” (State of Oklahoma, 2020). Although many places now are open for business, many people have not yet returned to work, have decreased wages or have health concerns that limit the activities in which they are willing to participate—all of which impact how quickly Oklahoma’s economy will recover from the early impacts of COVID-19. Additionally, those in public service, such as county educators with OSU Extension and others who hold group gatherings were left to make decisions regarding the re-start of in-person meetings while trying to consider the wishes and concerns of those involved. Given these elements, more information is needed to shed some light on resident’s beliefs regarding COVID-19 economic and social recovery within the state of Oklahoma.

Data Collection

An online survey instrument was created in Qualtrics, a program which allows for the design and dissemination of online surveys, with the intention of evaluating Oklahoma residents’ perceptions of the effect of COVID-19 on the local economy, timeline for recovery and comfort level with group meetings. This survey instrument was approved by Oklahoma State IRB number IRB-20-244. Data were collected between May 7, 2020 and June 5, 2020. Snowball sampling was used to contact respondents, first starting with existing email lists associated with OSU Extension. Additional recruitment posts were made on Facebook, Twitter and town newspapers in Oklahoma. Respondents were encouraged to forward the survey to those they thought would be interested in participating as part of the solicitation script.

In total, 815 people responded to the survey. The intention of the survey was to evaluate Oklahoma residents’ perceptions, but given how widely shared the survey became, some respondents from outside the state participated. Therefore, those respondents who did not select the county in Oklahoma they resided in, or indicated in the comment section at the end of the survey that they were not from Oklahoma were removed from the sample. In total, there were 796 responses to the survey that met the minimum criteria of completion. Given that each question was not mandatory in the survey, the number of respondents for each particular question will be included with the results. Each question was tabulated, and the percentage of respondents is presented. For Likert scale questions, the means as well as the tabulated percentages, are presented, with means statistically tested between categories using a t-test when appropriate.

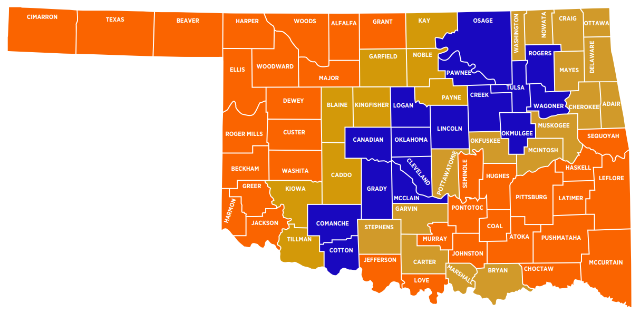

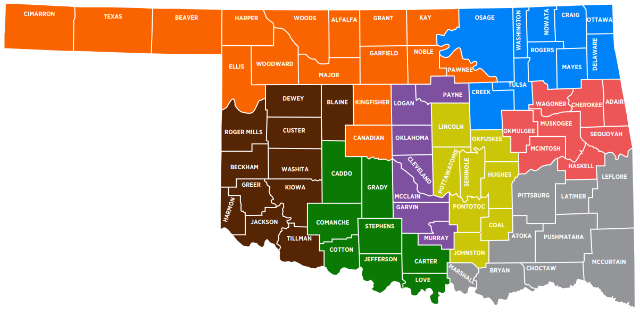

In addition to evaluating the full sample, further analysis regarding the top occupations was conducted. Differences between regions in Oklahoma were evaluated by breaking down the 77 Oklahoma counties based on two different criteria. The USDA has a rurality scale which ranges from 1 (a large metro of 1 million people or more) to 9 (a completely rural area of less than 2,500 people) (USDA, 2020a). A rurality score of 1 to 3 indicates a metro area, therefore the 9-point scale was condensed to 1 to 3 (rurality group 1), 4 to 6 (rurality group 2) and 7 to 9 (rurality group 3). As of the 2010 census, rurality group 1 made up 64% of the state population, rurality group 2 made up 25% of the population and rurality group 3 made up 11% of the state population. Oklahoma rurality scores are available in Appendix 1 (USDA, 2020b). Next, the Association of County Commissioners (ACCO) district definitions were used to parse the counties into eight distinct districts (ACCO, 2020). The districts as defined by the ACCO is available in Appendix 2.

Results and Discussion

Of the 77 counties in Oklahoma, there were respondents from all but six counties.

Payne (14%), Grady (9%), Oklahoma (7%), Muskogee (6%) and Tulsa (5%) counties had

the highest number of respondents (Table 1). The survey link was initially distributed

through county Extension educator contacts and social media, which may explain the

broad coverage across the state. Because the short survey focused on those who were

likely to be on an OSU Extension email list, the occupation list was fairly short.

Most respondents classified their occupation as other (22%) (Table 2). The second

highest occupation selected was education (17%), followed by farmer/rancher (15%)

and Extension (10%). Respondents could choose more than one occupation to reflect

multiple adults in the household or even multiple roles. For example, if a respondent

is a farmer who also holds an off-farm job, they might make two selections for occupation.

Unsurprisingly, when looking at the three rurality index categories, the percentage

of farmers/ranchers increased from rurality group 1 to rurality group 3, increasing

as the counties became more rural (Table 2). All rurality groups had high percentages

of respondents select other for occupation. In rurality groups 1 and 2, a high percentage

selected education (14% and 20% respectively). In rurality group 3, the highest percentage

of respondents were farmers/ranchers (23%). ACCO districts 2 to 5 had high percentages

of respondents who selected education as an occupation, while districts 6 to 8 had

high percentage select farmer/rancher (Table 3). District 1 had an almost equal percentage

of respondents select farmer/rancher (16%) and education (17%).

Table 1. Respondents county of residence n=796.

| County | Percentage of respondents |

County | Percentage of respondents |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payne | 13.90% | Wagoner | 0.60% | |

| Grady | 9.00% | Beckham | 0.50% | |

| Oklahoma | 7.20% | Grant | 0.50% | |

| Muskogee | 5.50% | Okfuskee | 0.50% | |

| Tulsa | 4.90% | Okmulgee | 0.50% | |

| Noble | 3.40% | Washita | 0.50% | |

| Cleveland | 3.30% | Beaver | 0.40% | |

| Pawnee | 2.90% | Bryan | 0.40% | |

| Texas | 2.90% | Jackson | 0.40% | |

| Washington | 2.40% | Kingfisher | 0.40% | |

| Mayes | 2.00% | McClain | 0.40% | |

| Rogers | 2.00% | Nowata | 0.40% | |

| Canadian | 1.90% | Seminole | 0.40% | |

| Cherokee | 1.90% | Tillman | 0.40% | |

| Osage | 1.80% | Alfalfa | 0.30% | |

| Garfield | 1.60% | Atoka | 0.30% | |

| Creek | 1.50% | Coal | 0.30% | |

| Logan | 1.50% | Cotton | 0.30% | |

| Caddo | 1.40% | Delaware | 0.30% | |

| McIntosh | 1.40% | Dewey | 0.30% | |

| Pittsburg | 1.40% | Ellis | 0.30% | |

| Hughes | 1.30% | Garvin | 0.30% | |

| Ottawa | 1.30% | Jefferson | 0.30% | |

| Pottawatomie | 1.30% | Kiowa | 0.30% | |

| Adair | 1.10% | Choctaw | 0.10% | |

| Kay | 1.10% | Harper | 0.10% | |

| Roger Mills | 1.10% | Latimer | 0.10% | |

| Craig | 1.00% | Le Flore | 0.10% | |

| Pontotoc | 1.00% | Marshall | 0.10% | |

| Blaine | 0.90% | McCurtain | 0.10% | |

| Comanche | 0.90% | Sequoyah | 0.10% | |

| Cimarron | 0.80% | Woods | 0.10% | |

| Lincoln | 0.80% | Greer | 0.00% | |

| Major | 0.80% | Harmon | 0.00% | |

| Stephens | 0.80% | Haskell | 0.00% | |

| Woodward | 0.80% | Love | 0.00% | |

| Carter | 0.60% | Murray | 0.00% | |

| Custer | 0.60% | Pushmataha | 0.00% | |

| Johnston | 0.60% | |||

Table 2. Occupations of respondents and all adults in the household. 796 respondents, 1,250 responses.

| Occupation | Full Sample n=796 selections=1,250 |

Rurality 1 n=315 selections=490 |

Rurality 2 n=365 selections=569 |

Rurality 3 n=116 selections=201 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmer/Rancher | 15% | 12% | 14% | 23% |

| Sales/Service | 8% | 11% | 6% | 8% |

| Entrepreneur | 4% | 4% | 3% | 2% |

| Banking | 3% | 3% | 3% | 4% |

| Insurance | 1% | 1% | 1% | 0% |

| Education | 17% | 14% | 20% | 14% |

| Extension | 10% | 6% | 13% | 12% |

| Government | 8% | 9% | 8% | 7% |

| Oil and Natural Gas | 4% | 6% | 2% | 4% |

| Technology and IT | 3% | 4% | 3% | 0% |

| Agribusiness | 5% | 5% | 4% | 8% |

| Other | 22% | 24% | 23% | 15% |

Table 3. Occupations of respondents and all adults in the household by district as defined by county commissioner districts.

| District 1 n=162 selections=241 |

District 2 n=89 selections=140 |

District 3 n=21 selections=32 |

District 4 n=48 selections=68 |

District 5 n=211 selections=333 |

District 6 n=105 selections=169 |

District 7 n=39 selections=69 |

District 8 n=121 selections=208 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmer/Rancher | 16% | 8% | 13% | 16% | 6% | 21% | 30% | 22% |

| Sales/Service | 7% | 9% | 9% | 7% | 10% | 8% | 4% | 7% |

| Entrepreneur | 6% | 2% | 3% | 3% | 5% | 4% | 1% | 1% |

| Banking | 2% | 1% | 3% | 3% | 2% | 3% | 3% | 7% |

| Insurance | 1% | 3% | 3% | 1% | 1% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Education | 17% | 21% | 28% | 19% | 20% | 12% | 7% | 15% |

| Extension | 4% | 9% | 16% | 16% | 13% | 8% | 13% | 11% |

| Government | 7% | 15% | 6% | 4% | 8% | 7% | 7% | 8% |

| Oil and Natural Gas | 5% | 3% | 0% | 1% | 3% | 7% | 3% | 3% |

| Technology and IT | 5% | 4% | 3% | 0% | 5% | 2% | 1% | 1% |

| Agribusiness | 3% | 2% | 3% | 3% | 4% | 7% | 16% | 8% |

| Other | 27% | 23% | 13% | 25% | 25% | 20% | 13% | 16% |

Strength of Economy comparison

Respondents were asked to indicate how strong they believed their local economy was on a scale from 1 (strong) to 5 (weak). When looking at the responses for January 2020, high percentages of respondents gave their local economy a score of 3 (average) or less (towards strong) (Table 4). The converse is true when looking at their selections for the current time period with the majority of respondents giving their local economy a score of 3 (average) or greater (towards weak). The most frequently selected category for the current economy was not the bleakest option, but instead a 4 (somewhat weak). The mean response on the scale was 2.07 for January 2020 and 3.90 for the current time period. These numbers are statistically different and indicate that respondents believed their local economy had weakened since January of 2020.

Table 4. How strong respondents believed their local economy was in January 2020, and the time they participated in the survey from 1 (Strong) to 5 (Weak). Full sample n=762.

| Level of strength | Jan 2020 | Currently |

|---|---|---|

| 1 (Strong) | 34% | 1% |

| 2 (Somewhat strong) | 33% | 6% |

| 3 (Average) | 26% | 20% |

| 4 (Somewhat Weak) | 5% | 48% |

| 5 (Weak) | 2% | 25% |

| Mean | 2.071 | 3.9 |

- Indicates mean is statistically different between January 2020 and currently.

In order to evaluate the change, the score selected for the current time period was subtracted from the score selected for January 2020. Since the scores ranged from 1 (strong) to 5 (weak) a more negative response indicated the respondent believed the economy got worse, with -4 being the maximum difference. For the full sample, the difference in scores was -1.82, indicating that on average, respondents did not believe the economy had gone from the extreme distance of strong to weak. When comparing the occupational breakdowns, there were no statistical differences found in the mean difference in scores between the occupations. It is important to note the question referred to the local economy and not the respondents’ personal finances. Although it is likely the impact COVID-19 had on personal finances differed by occupation, given shutdowns, lay-offs etc., when evaluating the top occupations of this studies opinion on their local economy, differences were not found.

Rural versus Urban Responses on Changes in Economic Strength

Conversely, when comparing the mean differences of the three rurality groups, all means were statically different (Table 5). The more urban areas, which are represented by rurality group 1, believed there was a greater decrease in economic strength between January 2020 and the current time period (mean -2.00). This coincides with urban areas demonstrating higher levels of unemployment from March to May (Whitacre, 2020), higher declines in revenue in food service (Willoughby et al., 2020), tourism (Siems, 2020) and small businesses in service industries (Arati, 2020). The two major urban counties, Oklahoma and Tulsa Counties, have a higher concentration of these businesses.

This decrease in economic strength lessened with increasing rurality from rurality group 2 to rurality group 3. Rurality groups 2 and 3, in general, had fewer cases than more urban counties at the time of the survey. This may have led respondents to feel more confident shopping at local businesses, but decreased longer distance travels to Oklahoma City and Tulsa for retail and dining. Further, participation in outdoor activities at lakes and state parks in May and June have already exceeded expectations from January (Siems, 2020). These outdoor venues tend to be in rurality groups 2 and 3, and such venues may be seen as an alternative to activities in urban areas that have likely been canceled or limited due to crowd sizes or to out-of-state vacation destinations. Such increases, while unlikely to fully offset economic impacts from the spring, may help offset losses in other sectors.

Given the immediacy of the impacts of closures and the shutdown of retail establishments that were more likely to impact urban communities, it is understandable that those in more urban communities would perceive a greater difference in economic strength in response to COVID-19. It may be some time before impacts for agriculture and local government are fully understood (Lansford, 2020; Raper and Peel, 2020; Hagerman and Anderson, 2020), but it is apparent the impacts of COVID-19 are far from over.

Table 5 (a) Economic score difference between the score respondent chose for January 2020 and

the current time.

(Full sample = Occupation + Rurality )

| Economic Score difference1 |

Full sample n=762 |

Farmer/Rancher n=180 |

Education n=208 |

Extension n=122 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -4 | 6% | 4% | 4% | 3% |

| -3 | 23% | 22% | 19% | 17% |

| -2 | 32% | 31% | 32% | 39% |

| -1 | 29% | 31% | 33% | 32% |

| 0 | 9% | 10% | 10% | 7% |

| 1 | 1% | 1% | 1% | 2% |

| 2 | 0% | 1% | 0% | 0% |

| Mean | -1.82 | -1.742 | -1.68 | -1.72 |

| Mean | -1.82 | -1.742 | -1.68 | -1.72 |

Table 5 (b). Economic score difference between the score respondent chose for January 2020 and

the current time.

(Full sample = Occupation + Rurality )

| Economic Score difference1 |

Full sample n=762 |

Rurality 1 n=302 |

Rurality 2 n=349 |

Rurality 3 n=111 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -4 | 6% | 8% | 5% | 5% |

| -3 | 23% | 27% | 21% | 14% |

| -2 | 32% | 32% | 33% | 26% |

| -1 | 29% | 23% | 32% | 34% |

| 0 | 9% | 8% | 8% | 15% |

| 1 | 1% | 1% | 1% | 3% |

| 2 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 2% |

| Mean | -1.82 | -2.003 | -1.78 | -1.45 |

- The economic difference score was calculated by subtracting the score respondents assigned the economy in January 2020 from the current date. The scores ranged from 1 (strong) to 5 (weak) therefore a more negative difference in scores indicates the respondent believed the economy got worse, with -4 being the maximum difference.

- The means between the different occupations are not statistically different at the <0.05 level.

- All means between the rurality classifications were statistically different at the <0.05 level.

Geographic Regional Differences in Responses on Economic Strength

Many statistical differences were found when evaluating the mean difference in economic scores across the ACCO districts (Table 6). The highest perceived difference in economic strength were found in districts 5, 6, 1 and 4. Districts 1 (Tulsa) and 5 (Oklahoma City) tend to be more metropolitan, while Districts 4 and 6 also have a strong metropolitan influence including suburbs of Oklahoma City. Other reports related to COVID-19 impacts indicate most job losses in the state were in metropolitan areas.

Table 6. Economic score difference between the score respondent chose for January 2020 and the current time for each district as defined by county commissioner districts.

| Economic Score Difference1 |

District 1 n=153 |

District 2 n=83 |

District 3 n=21 |

District 4 n=47 |

District 5 n=207 |

District 6 n=97 |

District 7 n=38 |

District 8 n=116 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -4 | 3% | 2% | 10% | 2% | 10% | 10% | 3% | 4% |

| -3 | 20% | 12% | 10% | 32% | 26% | 28% | 13% | 24% |

| -2 | 41% | 30% | 29% | 30% | 30% | 30% | 21% | 29% |

| -1 | 28% | 36% | 33% | 19% | 28% | 23% | 50% | 28% |

| 0 | 5% | 17% | 10% | 15% | 5% | 9% | 8% | 13% |

| 1 | 2% | 2% | 10% | 2% | 1% | 0% | 3% | 0% |

| 2 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 3% | 1% |

| Mean | -1.82ab2 | -1.4c | -1.48ac | -1.81abd | -2.04b | -2.07b | -1.34cde | -1.75ae |

- The economic difference score was calculated by subtracting the score respondents assigned the economy in January 2020 from the current date.The scores ranged from 1 (strong) to 5 (weak) therefore a more negative difference in scores indicates the respondent believed the economy got worse, with -4 being the maximum difference.

- Matching letters indicate the mean for those districts are not statistically different at the <0.05 level, differing letters indicate the means for those districts are different. For example, districts 1, 3, 4 and 8 all have a letter a indicating they are not statistically different. Conversely the mean for district 2 is statistically different from 1, 3, 4 and 8.

Anticipation of When the Worst Effects will be Over

Given the uncertainty surrounding COVID-19, it is not surprising that when asked when the worst effects of the current crises would be over, there are very few clear trends in responses. It is important to note that the definition of the worst effect was not provided to respondents. The worst part for some respondents may be the health implications of COVID-19, for others it may be the economic ramifications of shelter-in-place decrees, therefore the interpretation was left to the respondent. When evaluating the full sample, high percentages of respondents believed the worst effects of the current crisis would be over in four to six months (21%), 10 to 12 months (20%) and 13+ months (25%) (Table 7). Few respondents believed the worst of the effects of the crisis were over now (5%). The same trend holds true across the top occupations, with very few people thinking the worst effects are over now, and no notable differences across the occupations.

When comparing the rurality groups, rurality group 1 had a slightly higher percentage of respondents thought the worst was over now when compared to the two other groups (Table 7). High percentages of those in rurality group 2 thought the worst effects of the current crisis would be over in 13+ months (28%) and four to six months (23%). For rurality group 3, high percentages of respondents believed that the worst of the effects of the current crisis would be over in 10 to 12 months.

Table 7 (a). Number of months respondents anticipate it will be before the worst effects of the

current crisis will abate n=762.

(Full sample = Occupation + Rurality )

| Number of Months | Full Sample n=762 |

Farmer/Rancher n=183 |

Education n=211 |

Extension n=125 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Now | 5% | 3% | 2% | 2% |

| 1 to 3 months | 16% | 15% | 15% | 20% |

| 4 to 6 months | 21% | 18% | 18% | 22% |

| 7 to 9 months | 13% | 14% | 14% | 15% |

| 10 to 12 months | 20% | 22% | 23% | 20% |

| 13+ months | 25% | 27% | 28% | 21% |

Table 7 (b). Number of months respondents anticipate it will be before the worst effects of the

current crisis will abate n=762.

(Full sample = Occupation + Rurality )

| Number of Months | Full Sample n=762 |

Rurality 1 n=308 |

Rurality 2 n=360 |

Rurality 3 n=114 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Now | 5% | 7% | 3% | 5% |

| 1 to 3 months | 16% | 16% | 16% | 19% |

| 4 to 6 months | 21% | 20% | 23% | 18% |

| 7 to 9 months | 13% | 12% | 13% | 16% |

| 10 to 12 months | 20% | 20% | 18% | 24% |

| 13+ months | 25% | 25% | 28% | 18% |

When comparing the different ACCO districts, 8% of respondents in district 8 believed that the worst effects of the current crisis were over now (Table 8). Although this is slightly higher than the other districts, 30% of those in district 8 indicated that it would be 13+ months before the worst effects were finished. District 1 had a high percentage of respondents who believed the worst would be over in four to six months (27%) and district 8 had a high percentage that believed the worst would be over in four to six months (24%) and seven to nine months (24%). The important thing to note from these results is that most people, independent of occupation, region or district, believe that Oklahoma has a while to go before the worst effects of the current crisis are at an end.

Table 8. Number of months respondents anticipate it will be before the worst effects of the current crisis will abate for each district as defined by county commissioner districts.

| District 1 n=162 |

District 2 n=87 |

District 3 n=21 |

District 4 n=47 |

District 5 n=206 |

District 6 n=102 |

District 7 n=38 |

District 8 n=119 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Now | 6% | 1% | 0% | 6% | 8% | 2% | 3% | 4% |

| 1 to 3 months | 14% | 13% | 14% | 13% | 16% | 15% | 24% | 24% |

| 4 to 6 months | 27% | 17% | 29% | 23% | 15% | 23% | 16% | 24% |

| 7 to 9 months | 15% | 21% | 5% | 13% | 11% | 8% | 11% | 16% |

| 10 to 12 months | 19% | 17% | 19% | 21% | 21% | 20% | 29% | 16% |

| 13+ months | 19% | 31% | 33% | 23% | 30% | 33% | 18% | 16% |

Comfort Level with Group Meetings

Respondents were asked when they would be comfortable attending, or sending an employee or family member to an in-person training of more than 10 people, assuming social distancing protocols would be in place. If they chose any answer other than now, they then participated in a second question asking the same thing, but instead for groups of 10 people or less. It was assumed that if the respondent was comfortable with a meeting of 10 people or more now, they would also be comfortable with a meeting of 10 people or less now. For the full sample, 41% of respondents were comfortable with an in-person meeting of more than 10 people now (Table 9). Eighteen percent of respondents selected only at the recommendation of the CDC/health department or government and 6% selected only when a vaccine is available.

When considering groups of 10 people or less, 56% of the full sample would be comfortable with a meeting now. Of those who were not comfortable with a meeting of 10 or more people now, 24% of respondents would only be comfortable with a meeting of 10 people or less at the recommendation of the CDC/health department or government and 5% would only be comfortable when there is a vaccine (Table 10). Although more than 50% of respondents are comfortable with a meeting of 10 people or less now, there are still many people who are not. It is important to consider including alternative options to in-person meetings to accommodate those who are not comfortable.

Table 9 (a). When respondents would feel comfortable attending, or sending an employee or family member to, in-person meetings/trainings etc. of more than 10 people (assuming social distancing protocols will be in place).

(Full sample = Occupation + Rurality )

| Amount of time | Full sample n=794 |

Farmer/Rancher n=186 |

Education n=100 |

Extension n=126 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Now | 41% | 49% | 36% | 27% |

| 1 to 3 months | 20% | 21% | 18% | 26% |

| 4 to 6 months | 9% | 6% | 11% | 10% |

| 7 to 9 months | 3% | 1% | 2% | 2% |

| 10 to 12 months | 2% | 2% | 3% | 6% |

| 13+ months | 1% | 2% | 2% | 0% |

| Only at the recommendation of CDC/health department/ government |

18% | 14% | 20% | 22% |

| Only when a vaccine is available | 6% | 4% | 8% | 6% |

Table 9 (b). When respondents would feel comfortable attending, or sending an employee or family member to, in-person meetings/trainings etc. of more than 10 people (assuming social distancing protocols will be in place).

(Full sample = Occupation + Rurality )

| Amount of time | Full sample n=794 |

Rurality 1 n=314 |

Rurality 2 n=364 |

Rurality 3 n=116 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Now | 41% | 41% | 37% | 51% |

| 1 to 3 months | 20% | 17% | 22% | 25% |

| 4 to 6 months | 9% | 10% | 10% | 5% |

| 7 to 9 months | 3% | 3% | 2% | 3% |

| 10 to 12 months | 2% | 2% | 2% | 3% |

| 13+ months | 1% | 1% | 2% | 1% |

| Only at the recommendation of CDC/health department/ government |

18% | 20% | 20% | 9% |

| Only when a vaccine is available | 6% | 6% | 5% | 4% |

Looking at the breakdown of the top occupations from the study a potential point of contention becomes apparent. Forty-nine percent of farmers/ranchers are comfortable with meetings of more than 10 people, while only 27% of county educators were comfortable (Table 9). Considering the importance of Extension-led/facilitated meetings for farmer/ranchers, communications regarding meeting expectations will be paramount. When considering meetings of less than 10 people, 59% of farmers/ranchers were comfortable and 54% of Extension educators were comfortable with having a meeting now (Table 10). Those in education fall between farmers/ranchers and Extension in their willingness to participate in meetings of less than and greater than 10 people. Despite the high percentages of farmers/ranchers who are willing to participate in meetings of 10 people or less now, 7% of those who are not willing to participate in a meeting of greater than 10 now also are only willing to participate in a meeting of less than 10 when a vaccine is available.

Table 10 (a). When respondents would feel comfortable attending, or sending an employee or family

member to, in-person meetings/trainings etc. of less than 10 people (assuming social

distancing protocols will be in place).

(Full sample = Occupation + Rurality )

| Amount | Full sample n=4541 |

Farmer/Rancher n=88 |

Education n=131 |

Extension n=92 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Now | 24% | 19% | 23% | 24% |

| 1 to 3 months | 28% | 32% | 26% | 32% |

| 4 to 6 months | 12% | 14% | 11% | 16% |

| 7 to 9 months | 4% | 1% | 2% | 1% |

| 10 to 12 months | 2% | 1% | 5% | 4% |

| 13+ months | 1% | 2% | 2% | 0% |

| Only at the recommendation of CDC / health department / government | 24% | 24% | 27% | 22% |

| Only when a vaccine is available | 5% | 7% | 5% | 1% |

- If the respondent indicated they were not comfortable going to a meeting with over 10 people now, they were then asked their comfort level for less than 10 people. Therefore 56% of the total sample was comfortable with a meeting of less than 10 people now. From demographic categories 59%, 50% and 54% of respondents with the occupations farmer/rancher, education and extension were comfortable with a meeting of less than 10 people right now. From rurality category 1 to 3, 55%, 51% and 66% of the total sample for that rurality category was comfortable with a meeting of less than 10 people now.

Table 10 (b). When respondents would feel comfortable attending, or sending an employee or family

member to, in-person meetings/trainings etc. of less than 10 people (assuming social

distancing protocols will be in place).

(Full sample = Occupation + Rurality )

| Amount | Full sample n=4541 |

Rurality 1 n=179 |

Rurality 2 n=220 |

Rurality 3 n=55 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Now | 24% | 23% | 23% | 33% |

| 1 to 3 months | 28% | 25% | 30% | 31% |

| 4 to 6 months | 12% | 15% | 11% | 4% |

| 7 to 9 months | 4% | 5% | 3% | 4% |

| 10 to 12 months | 2% | 0% | 3% | 5% |

| 13+ months | 1% | 0% | 2% | 2% |

| Only at the recommendation of CDC / health department / government | 24% | 28% | 23% | 13% |

| Only when a vaccine is available | 5% | 4% | 4% | 9% |

- If the respondent indicated they were not comfortable going to a meeting with over

10 people now, they were then asked their comfort level for less than 10 people. Therefore

56% of the total sample was comfortable with a meeting of less than 10 people now.

From demographic categories 59%, 50% and 54% of respondents with the occupations farmer/rancher,

education and extension were comfortable with a meeting of less than 10 people right

now. From rurality category 1 to 3, 55%, 51% and 66% of the total sample for that

rurality category was comfortable with a meeting of less than 10 people now.

A higher percent of people in rurality group 3 (more rural areas) were comfortable with a meeting of greater than 10 people (51%) when compared to rurality group 1 (41%) and rurality group 2 (37%). The opposite is true when looking at the category only at the recommendation of the CDC/health department/government with only 9% of rurality group 3 choosing this option and 20% each for rurality group 1 and rurality group 2 choosing this option for more than 10 people. Almost 75% of Oklahoma counties are in rurality group 2 or rurality group 3 based on the USDA-ERS Rural Urban Continuum Code. Of those non-metropolitan counties, only seven counties in the state had infection rates above the national average as of May 27 (Woods, 2020). This lower incidence of infection in rural areas of the state as compared to urban and high population density areas may, in part, explain the comfort level with group meetings. However, that result may change should disease incidences spike in rural areas. The comfort level of participating in a group of less than 10 people also increases with rurality level with 55% of rurality group 1, 51% of rurality group 2 and 66% of rurality group 3 indicating they were comfortable now. For rurality group 1 and 2, high percentages of those who were not comfortable with meetings of greater than 10 now, were only comfortable with meetings of less than 10 at the recommendation of the CDC/health department/government. Additionally, for rurality group 3, 9% of respondents would only be comfortable with in-person meetings of less than 10 people when a vaccine is available.

Comparing the ACCO districts, high percentages of respondents in district 4 (44%), district 7 (54%) and district 8 (50%) were willing to participate in a meeting of more than 10 people now (Table 11). In districts 2 and 5, high percentages of respondents were only willing to participate in a meeting of more than 10 people at the recommendation of the CDC/health department/government. Ten percent of respondents in districts 4 and 5 were only willing to participate in meetings of more than 10 people when a vaccine has been found. From district 1 to 8 respectively, 55%, 46%, 52%, 50%, 50%, 61%, 69% and 62% of the total sample for that district were comfortable with a meeting of less than 10 people now. Of the respondents who were not comfortable participating in a meeting of greater than 10 people now, 31% of people in districts 2 and 3 would participate in a meeting of less than 10 people only at the recommendation of the CDC/health department/government. Of the respondents in district 4 who were not comfortable participating in a meeting of greater than 10 people now, 15% would only participate in a meeting of less than 10 people if a vaccine was found.

Table 11. When respondents would feel comfortable attending, or sending an employee or family member to, in-person meetings/trainings etc. of more than 10 people (assuming social distancing protocols will be in place) for each district as defined by county commissioner districts.

| District 1 n=161 |

District 2 n=89 |

District 3 n=21 |

District 4 n=48 |

District 5 n=211 |

District 6 n=104 |

District 7 n=39 |

District 8 n=121 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Now | 40% | 34% | 38% | 44% | 38% | 38% | 54% | 50% |

| 1-3 months | 21% | 22% | 29% | 29% | 12% | 22% | 15% | 26% |

| 4-6 months | 12% | 8% | 14% | 4% | 9% | 10% | 10% | 9% |

| 7-9 months | 3% | 0% | 0% | 4% | 4% | 2% | 5% | 1% |

| 10-12 months | 2% | 3% | 5% | 2% | 3% | 0% | 0% | 2% |

| 13+ months | 0% | 2% | 5% | 0% | 1% | 3% | 3% | 0% |

| Only at the recommendation of CDC / health department/ government | 18% | 28% | 10% | 6% | 23% | 18% | 13% | 9% |

| Only when a vaccine is available | 4% | 2% | 0% | 10% | 10% | 7% | 0% | 2% |

Table 12. When respondents would feel comfortable attending, or sending an employee or family member to, in-person meetings/trainings etc. of less than 10 people (assuming social distancing protocols will be in place).1

| District 1 n=91 |

District 2 n=55 |

District 3 n=13 |

District 4 n=27 |

District 5 n=131 |

District 6 n=62 |

District 7 n=17 |

District 8 n=58 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Now | 26% | 20% | 23% | 11% | 20% | 37% | 35% | 26% |

| 1-3 months | 27% | 35% | 46% | 44% | 22% | 13% | 35% | 38% |

| 4-6 months | 19% | 5% | 8% | 4% | 11% | 13% | 12% | 10% |

| 7-9 months | 3% | 0% | 0% | 7% | 5% | 3% | 6% | 3% |

| 10-12 months | 1% | 4% | 8% | 0% | 3% | 0% | 0% | 3% |

| 13+ months | 1% | 2% | 8% | 0% | 1% | 2% | 6% | 0% |

| Only at the recommendation of CDC/health department/government | 21% | 31% | 8% | 19% | 31% | 24% | 0% | 17% |

| Only when a vaccine is available | 1% | 4% | 0% | 15% | 7% | 8% | 6% | 2% |

- If the respondent indicated they were not comfortable going to a meeting with over 10 people now, they were then asked their comfort level for less than 10 people. Therefore from district 1 to 8 respectively, 55%, 46%, 52%, 50%, 50%, 61%, 69% and 62% of the total sample for that district was comfortable with a meeting of less than 10 people now.

Conclusion

This report details results from a survey of respondents across 71 of Oklahoma’s 77 counties. When not selecting other, respondents tended to report the occupation of those in the household as farmer/rancher, educator or extension educator. It should be noted the survey population was built from email lists of individuals associated with OSU Extension and the snowball method was used to recruit other respondents. Therefore, the sample is not representative of the entire population of Oklahoma. These results can be used alongside other statistics collected during the same time period to enhance recovery in the state. COVID-19 impacted every level of the economy, and it will take time before the impacts are fully known. Respondents in rural areas felt the economy had deteriorated less than those in more urban areas. Additionally, responses by county commissioner districts tended to show metropolitan influences consistent with other findings including that metropolitan areas lost more employment and were perceived to be harder hit by the pandemic. Although approximately half of respondents were comfortable with an in-person meeting given all social distancing protocols were followed for meetings of less than 10, many people were uncomfortable with in-person meetings. Those conducting/hosting/facilitating meetings should take into consideration the lack of comfort many people have with meetings of even less than 10 people when planning alternative ways to participate. An additional challenging variable is how the pandemic declines or surges. Personal choices and perceptions will vary as new and more current information is made available over the coming weeks.

Works Cited

- Analysis of Known and Potential Impacts of COVID-19 on Local Governments, Lansford, 2020

- Association of county commissioners (ACCO). 2020. Available online https://www.okacco.com/

- CDC. 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Summary. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/summary.html.

- COVID-19 Employment Outlook Across Oklahoma Counties Whitacre, 2020

- Economic Impact of COVID-19 on Oklahoma Livestock and Broiler Industries, Raper and Peel, 2020

- Estimating the Impact of COVID-19 on Oklahoma’s Food Industry Willoughby et al., 2020

- Impact of the COVID-19 Virus on Agriculture and Rural Oklahoma, Woods, 2020

- Impact of COVID-19 on the Small Business Sector Arati, 2020

- New York Times. 2020. Oklahoma Coronavirus Map and Case Count. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/oklahoma-coronavirus-cases.html

- News 9, 2020. COVID-19 In Oklahoma: What is a non-essential Business? Available online: https://www.news9.com/story/5e7e3af1065c486efd6d1727/covid19-in-oklahoma:-what-is-a-nonessential-business

- State of Oklahoma. Governor Stitt announces “Open us and recover safely” plan. Available online: https://www.governor.ok.gov/articles/press_releases/gov-stitt-announces-open-up-and-recovery-plan

- The COVID-19 Impact on Oklahoma Crop Producers, Hagerman and Anderson, 2020

- USDA. 2020a. Rural Urban Continuum codes. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/documentation/

- USDA. 2020b. Rural Urban Continuum codes for Oklahoma. Available online:https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes.aspx

Appendix 1.

Oklahoma counties grouped by USDA rurality index.

| Rurality code 1 to 3 | Rurality code 4 to 6 | Rurality code 7 to 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Figure 1. Map of USDA rurality index. Rurality group 1 is indicated by blue, 2 is indicated by gold and 3 is indicate by orange.

| District 1 | District 2 | District 3 | District 4 | District 5 | District 6 | District 7 | District 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 2. Map of ACCO districts.

Courtney Bir

Extension Economist

Amy Hagerman

Ag and Food Policy Extension Specialist

Mike Woods

Professor Emeritus

Department of Agricultural Economics