Effects of Lead Ammunition and Sinkers on Wildlife

Introduction

This document is intended to provide information on the effects of lead on wildlife species from recreational sport hunting and fishing. Discussion and interest on this subject has been growing within the hunting, fishing and natural resource communities. The purpose of this summary is to assist hunters and anglers in making informed decisions. Lead in ammunition and fishing tackle is restricted on some public lands and in some states, and additional bans may occur in the future. It is necessary for the public to understand the issue so they can provide input on future management actions. Relevant information has been assembled, and alternatives are provided to hunters and anglers. The purpose of this document is to encourage readers to consider the effects of lead on the environment.

Background

Lead is a heavy metal designated as Pb in the periodic elements table. It is known as a nonessential element to biological life. However, it has been found to be a useful material in many applications. This metal has been used by humans for centuries because it is abundant and easy to smelt. Its malleability, low cost and density have made it attractive for ammunition and lead weights in fishing tackle. Unfortunately, lead is also extremely toxic. The metal has been shown to cause anemia, neurological impairment and immune system impairment. A major problem with lead is that it bioaccumulates in animal tissue. This means it is absorbed at a faster rate than it is expelled, and toxic levels can be reached if the lead continues to be absorbed. Due to these serious health issues, the U.S. banned lead from paint in 1977, plumbing used for drinking water in 1986 and gasoline in 1996. However, it is still widely used in other applications, such as ammunition and weights (e.g., lead sinkers for fishing tackle). While lead has been linked to human health concerns for centuries, only recently has its harm to wildlife been addressed. Lead is especially problematic for birds since it can accumulate in a bird’s gizzard where it is continually ground into smaller particles and readily absorbed into the blood stream.

Sources and Amount of Lead

The primary sources of lead from sporting activities are from lead shot, bullets and fishing weights. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that about 70,000 tons of lead are deposited at shooting ranges each year. While this presents many water quality challenges, the more direct threat to wildlife is lead deposited in the field while hunting and fishing. Prior to the lead ban for waterfowl hunting, it was estimated that more than 2,700 tons of shot where deposited in wetlands each year. Most troubling was waterfowl tend to congregate in large numbers, so waterfowl hunting and lead shot tended to be concentrated. Likewise, dove hunting may be concentrated on prepared dove food plots and harvested agriculture fields. It has been estimated that more than 2.5 million pellets per acre are deposited each year in some of these dove fields. While lead bullets from rifle hunting contribute far less total lead into the environment, fragments remaining in animal carcasses or gut piles left in the field can be hazardous to scavenging animals.

Lead is also used extensively in fishing. It has been estimated that over 4,000 tons of lead sinkers are purchased in the U.S. each year. While it is not known how much of that is deposited into the aquatic environment, it is assumed that a high percentage of this lead is lost each year. Various studies have examined the amount of lead along shorelines, and the results have ranged from almost none up to more than 100 pieces per square yard in heavily fished areas.

The availability of lead shot, bullets and fishing tackle is dependent on the depth of the lead in the soil. In grassland and forest settings, the lead may be available only for a short time before litter covers it. However, in crop fields, lead may be covered and then uncovered annually through cultivation. Additionally, management practices, such as fire, grazing and discing, can make it available. Therefore, the long-term persistence can be for many years, depending on the management of the site. In aquatic systems, lead has been found to accumulate at the top of the sediment and remain there for long periods of time. Lead breaks down within 100 to 300 years, and is no longer available for direct ingestion by wildlife, but it can then enter the water system and potentially poison wildlife and people.

Effects of Wildlife

Ingestion of Lead by Birds

There are several ways birds can consume lead. It can be consumed in contaminated plant material, sediment or animal carcasses. It may even be mistaken for food or grit, which is used in the gizzard to grind food. These last two examples are the most common. Incidental exposure of lead from pellets lodged in the skin or other tissue appears to be of minimal concern as lead is not easily absorbed into the bloodstream through tissue.

The earliest records for effects on birds involved waterfowl in the late 1800s, but it would be several decades before the full impacts were realized. Waterfowl are particularly vulnerable to lead due to the high concentration and availability of lead shot on bare soil (prepared fields) and in shallow wetlands. As few as one or two lead pellets can kill waterfowl. Even if mortality does not occur, poisoned waterfowl have depressed activity and are more at risk for harvest or predation. Prior to the lead ban, estimates of waterfowl mortality in the U.S. ranged from 1.6 to 3.9 million birds per year. The ban on lead for waterfowl hunting has led to a 50% reduction of lead ingestion by waterfowl, saving an estimated 1.4 million ducks annually. One #4 lead pellet has negative effects for three months after ingestion.

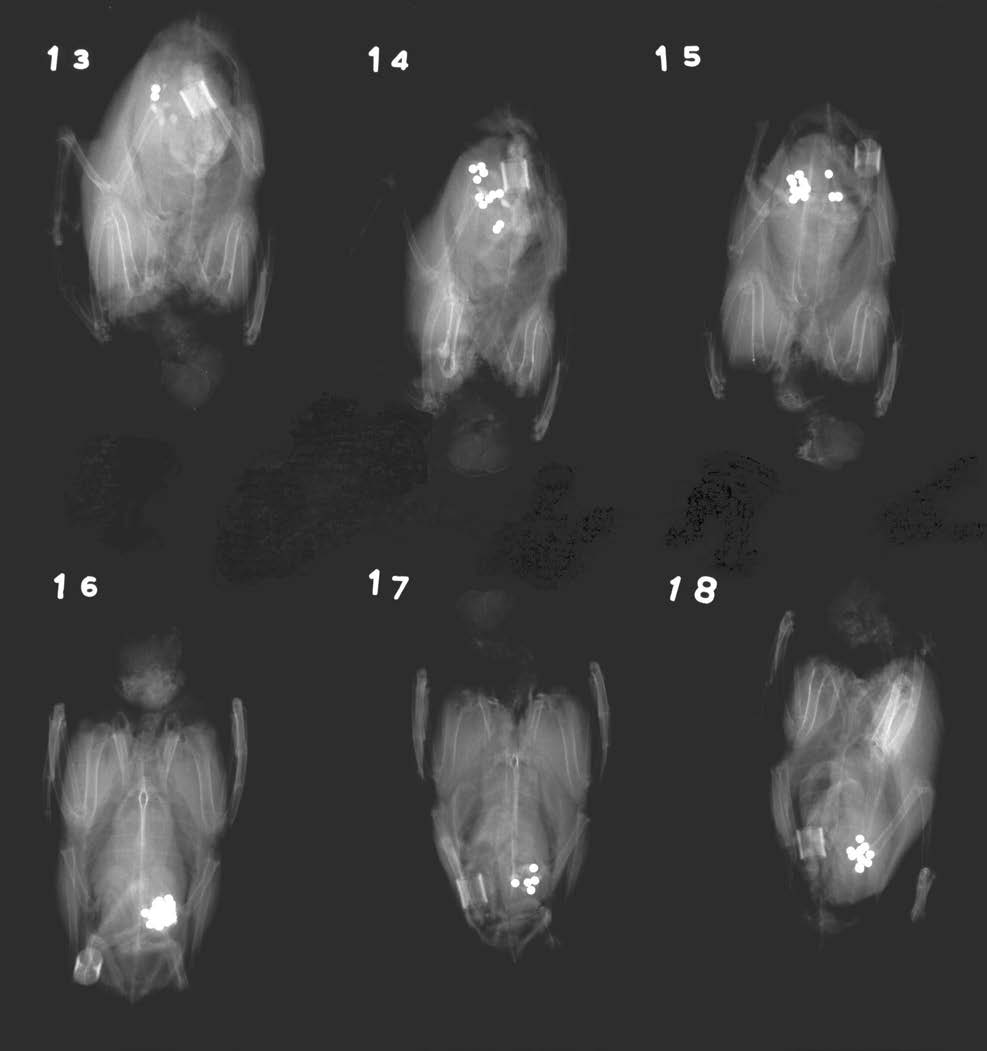

Upland game birds are also susceptible to lead poisoning. Lead effects have been documented for virtually every species of upland game bird in the U.S., including ring-necked pheasant, northern bobwhite, chukar and wild turkey, but no other upland game bird is more at risk than the mourning dove. The primary reason for their susceptibility is the same as waterfowl—concentrated hunting. Some dove fields collect more than 2.5 million pellets per acre each year. Since the ground is often bare or nearly bare in prepared fields, lead is more available for ingestion. Also, the size shot commonly used for dove hunting is very similar to seeds consumed by the mourning dove (Figure 1). Doves have difficulty maintaining their core body temperature after ingesting lead and appear to die rapidly. As few as two pellets can kill a mourning dove, but doves often consume multiple pellets (Figure 2). Chukar may also be susceptible to ingestion of lead because they frequently use water sources where concentrated shooting can occur. Additionally, the vegetation community that chukar inhabit typically consists of a high amount of bare ground. Research in Utah has demonstrated that up to 11% of wild chukar have lead exposure, and as few as one lead pellet can kill a chukar. While it is known that lead is consumed by many species of upland game birds, information on the population effects of lead ingestion for most species is lacking. Further, there is little known about the effects of lead on passerine bird species (e.g., sparrows, thrushes, etc.), but it is likely that lead is most detrimental to species that forage on the ground.

Figure 1. Popular shot sizes for bird hunting are similar in size to many preferred game bird foods. Clockwise from top left, #6 lead shot, #8 lead shot, wooly croton seed and Pennsylvania smartweed seed.

Figure 2. Lead shot ingested by mourning doves is apparent in these X-ray images. Note the bright areas indicating the dense lead shot. (Courtesy of Missouri Department of Conservation)

Lead ingestion is not limited to shot; fishing tackle is also a concern for some aquatic birds. Swans, geese, ducks, pelicans and loons have died from lead poisoning. Lead tackle under 2 ounces is most often consumed. Loons probably ingest the lead incidentally as they are eating bait off broken fishing lines. Some studies have found that about half of all loon mortalities are due to lead poisoning. Swans all over the world also have high mortality from lead. In fact, 90% of the mortality of certain mute swan populations in Britain was due to lead poisoning from fishing tackle.

Raptor and Scavenger Effects

Consumption of lead shot, bullets or bullet fragments has been a major mortality cause for imperiled birds of prey and scavengers. Through 1996, there were five states where at least 20 bald eagles died from ingesting lead from carcasses. This is a continual problem for the endangered California condor in California, Utah and Arizona, where strategies to reduce lead poisoning may include capturing birds to cleanse lead from the blood, cleaning up gut piles and having both mandatory and voluntary “no lead” zones for big game hunting. Any unrecovered or wounded animal shot with lead ammunition could potentially cause lead poisoning mortality of a bird of prey. Lead poisoning can also occur in scavenging mammals, such as coyotes, wolves and foxes, but because mammals pass lead pieces through their digestive system quickly, it is not usually fatal.

Alternatives for Lead

Just as non-toxic alternatives have been available for waterfowl hunters for decades, there are readily available alternatives for upland gamebird hunting and big game hunting. Copper or brass bullets are available in virtually every rifle and handgun caliber. Ballistics for copper or brass bullets are similar to lead, and weight retention during penetration is usually superior. In fact, the U.S. military is in the process of making a transition to non-lead ammunition. Additionally, frangible bullets, composed of densely packed non-lead alloy powders, some with copper jackets and some unjacketed, are widely used now for law enforcement and personal defense. They are also available in some hunting calibers. These frangible bullets have the obvious advantage that there is little or none of the projectile remaining from complete penetration or ricochet. For shot, various alloys of tungsten and bismuth shot are available, but steel shot has been the most popular choice due to lower costs and higher availability. The main things to know when using steel shot is to use larger shot (because it is less dense than lead) and a more open choke (because it does not deform like lead). General recommendations are as follows:

- Go up two shot sizes to achieve similar effectiveness. For example, if you typically shoot #8 lead, change to #6 steel.

- Use a slightly heavier load. For example, if you typically use 1 oz. lead loads, use 1 1/8 oz. when shooting steel. This will adjust for the decreased pellet count associated with increased shot size (see Table 1).

- Use a more open choke. For example, if you would typically use a modified choke for lead shot, change to an improved cylinder or skeet choke for steel.

- Pattern your gun to determine the best choke/shot size/ shot weight combination for your needs.

- Avoid shooting steel shot through old guns or really tight chokes, which could cause barrel damage.

- Table 1 should serve as a good starting point.

Some hunters are concerned about the cost of using non-toxic shot. While premium alloy loads can cost considerably more than lead shot, steel loads are priced comparably to lead. There are also many non-toxic alternatives for lead fishing weights. Metals, such as steel, brass and tungsten, are produced in an array of sizes and types. Steel and brass are less dense than lead, thus the size for an equivalent weight will be larger. Tungsten is actually denser than lead. None of these alternatives are as pliable as lead.

At one time, there were close to 400 lead smelting plants in the U.S., but in December 2013, the last lead smelting plant in the U. S., Missouri’s Doe Run, was closed by the EPA. This does not mean we will suddenly experience a lead shortage, as vast stockpiles of lead bullion exists, and newer smelting plants that can meet the strict clean air guidelines set by the EPA may eventually be built to augment the couple of dozen major lead smelting plants in other countries. As the cost of lead inevitably rises, the production of non-toxic ammunition will likely continue its rapid ascent. The complete transformation to non-toxic ammunition may be forthcoming in the near future.

| Size | Shot wt. | Pellets |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | 1 | 135 |

| 4 | 1 1/8 | 152 |

| 4 | 1 1/4 | 169 |

| 5 | 1 | 170 |

| 5 | 1 1/8 | 191 |

| 6 | 7/8 | 203 |

| 6 | 1 | 232 |

| 6 | 1 1/8 | 251 |

| 6 | 1 1/4 | 276 |

| 7.5 | 7/8 | 302 |

| 7.5 | 1 | 345 |

| 7.5 | 1 1/8 | 388 |

| 7.5 | 1 1/4 | 431 |

| 8 | 7/8 | 358 |

| 8 | 1 | 409 |

| 8 | 1 1/8 | 461 |

| 8 | 1 1/4 | 511 |

Table 1. Non-toxic equivalents for common lead shot sizes.

| Size | Shot wt. | Pellets |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 1/8 | 141 |

| 2 | 1 1/4 | 156 |

| 2 | 1 3/8 | 170 |

| 3 | 1 1/8 | 175 |

| 3 | 1 1/4 | 194 |

| 4 | 1 | 189 |

| 4 | 1 1/8 | 212 |

| 4 | 1 1/4 | 237 |

| 4 | 1 3/8 | 260 |

| 5 | 1 | 243 |

| 5 | 1 1/8 | 274 |

| 5 | 1 1/4 | 304 |

| 5 | 1 3/8 | 334 |

| 6 | 1 | 314 |

| 6 | 1 1/8 | 335 |

| 6 | 1 1/4 | 294 |

| 6 | 1 3/8 | 433 |

Table 1. Cont. Non-toxic equivalents for common lead shot sizes

Current Restrictions on Lead

In the U.S., non-toxic shot is required for all waterfowl hunting, including ducks, geese, swans and coots. Several states have specific lead regulations beyond the federal restrictions, many requiring non-toxic shot on certain management units or statewide. Additionally, many public hunting areas have toxic shot regulations. Waterfowl Production Areas and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service refuges generally require non-toxic shot for hunting upland bird species because these areas are managed primarily for waterfowl and often contain numerous wetlands.

Some species-specific issues have lead to both mandatory and voluntary lead limitation. For example, areas supporting the federally endangered California condor have regulations to reduce condors consuming lead-contaminated big game carcasses. California requires non-toxic ammunition for big game hunting in areas where condors occur, and both Arizona and Utah provide vouchers to hunters to purchase non-toxic rifle ammunition in the areas of those states where condors occur. This voluntary program has been popular with hunters (with more than 80% compliance)and moderately effective at reducing lead risk to the California condor. Hunters are also encouraged to remove potentially contaminated gut piles. Additionally, California implemented a statewide ban on all lead ammunition in 2019.

Several states also have restrictions on lead in sport fishing, and many federal lands restrict lead for fishing. Other countries, such as the United Kingdom, have banned lead fishing tackle altogether.

It is difficult to gauge the success of lead bans on wildlife populations due to limited information. However, the ban on lead for waterfowl has greatly reduced the availability of lead and the associated mortality of waterfowl. Yet many hunters and anglers are understandably concerned about the effects any future restrictions might have on their outdoor activities. A common concern is that lead bans will increase the cost of hunting and fishing to the point that hunter and angler numbers will drop. Based on past experience with lead restrictions in waterfowl hunting, we expect an initial drop in hunter numbers. As waterfowl populations increased in the 1990s, the number of hunters followed. In fact, the number of federal duck stamps sold only dipped during the 1992 season from 1.43 million to 1.35 million hunters. The following year, it was back to 1.4 million and continued to rise to a high of 1.7 million hunters in 1997. Therefore, it is questionable that a complete ban on lead in ammunition and fishing tackle would contribute to large, continued declines in hunting and fishing activities.

Summary

It is likely that in the coming years, there will be continued restrictions placed on the use of lead ammunition and fishing tackle. Additionally, the EPA at some point may completely restrict the use of lead, which will by default, eliminate its use in hunting and fishing activities and recreational shooting. Voluntary restrictions are much preferred over regulation by most people. As hunters and anglers, it is our responsibility to limit the negative effects we might have on wildlife populations and natural resources. There is ample data to indicate that lead has negative consequences for many wildlife species. Additionally, non-toxic alternatives exist for nearly every application where lead is currently used. As supply and options continue to increase for non-toxic alternatives, price should decrease.

We encourage each hunter, angler and recreational shooter to carefully consider how they might voluntarily reduce impacts to wildlife by restricting the use of lead. This would have a positive impact on wildlife and ensure hunters and anglers continue to provide stewardship for not only game species but for all our nation’s wildlife resources.

For Additional Information

Rattner, B.A., J.C. Franson, S.R. Sheffeld, C.I. Goddard, N.J. Leonard, D. Stang, and P.J. Wingate. 2009. Technical Review of the Sources and Implications of Lead Ammunition and Fishing Tackle to Natural Resources. In: R. T. Watson, M. Fuller, M. Pokras, and W. G. Hunt (Eds.). Ingestion of Lead from Spent Ammunition: Implications for Wildlife and Humans. The Peregrine Fund, Boise, Idaho, USA. DOI 10.4080/ilsa.2009.0106.

Ellis, M. B., and C. A. Miller. 2022. The effect of a ban on the use of lead ammunition for waterfowl hunting on duck and goose crippling rates in Illinois. Wildlife Biology 2022: e01001, doi: 10.1002/wlb3.01001.P.J. Wingate. Sources and Implications of Lead based Ammunition and Fishing Tackle to Natural Resources. Wildlife Society Technical Review. The Wildlife Society, Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

Sapp, R. 2010. Gun Digest Book of Green Shooting – A practical guide to non-toxic hunting and regulation. Krause Publications, Iola, WI.

Thomas, V. G. 2013. Lead-free hunting rifle ammunition: product availability, price, effectiveness, and role in global wildlife conservation. AMBIO 42:737-745.

Non Lead Ammo - Peregrine Fund.

How Effective is Steel Shot? - Project Upland.