Corn Leafhopper Leads to Corn Stunt Disease Across Oklahoma – August 12, 2024

We documented and confirmed the first reports of corn leafhoppers, Dalbulus maidis (DeLong & Wolcott), and corn stunt disease in parts of Oklahoma this past week. Corn leafhopper and one of the pathogens associated with corn stunt disease have been confirmed in Pottawatomie County. However, corn leafhoppers and symptoms of corn stunt have been observed in several counties located in the West Central, Central, North Central, and Southwest districts. There have been many reports over the past week from Extension Specialists, consultants, and industry personnel about corn stunt disease and corn leafhoppers across Oklahoma. Our neighbors to the south have seen similar issues over the past couple of weeks, with large corn leafhopper populations reported up to San Angelo and into Comanche, TX, per Texas A&M AgriLife. Corn stunt disease results in yield loss due to severe plant stunting and loose/lost kernels. In this pest alert, we present information on insect and corn stunt disease symptoms, as well as management guidance for corn producers to implement in future growing seasons.

Insect Description

The corn leafhopper, Dalbulus maidis, is light tan/yellow in color and about 1/8” long (Figures 1A, B). The characteristic that distinguishes them from other leafhoppers is two dark spots located between their eyes in adults (Figure 2). They also have a smooth head, and the hind margin of the first thoracic segment forms a deeply indented ‘V’ shape (Figure 2). Nymphs are wingless and are similar in appearance to adults. Corn leafhoppers move rapidly within and among corn fields, and they fly or jump away when disturbed. They can be found in shaded areas of corn, resting and feeding in the whorl of young, developing plants, and hidden in the shade of leaves. Dalbulus maidis can transmit multiple pathogens associated with corn stunt disease.

| Image | Caption |

|---|---|

|

Figure 1. A) Corn leafhoppers, Dalbulus maidis, in shade of leaf. |

|

Figure 1 B) Close up of single corn leafhopper. Photographs by Ashleigh M. Faris. |

Figure 2. Corn leafhopper, Dalbulus maidis, photographed with microscope. Note two dark spots between eyes as distinguishing characteristic and the deeply indented ‘V’ shape of the first thoracic segment. Photograph by Ashleigh M. Faris.

Corn Leafhopper Distribution and Hosts

Corn leafhoppers are widely distributed from South America to the southern United States (Figure 3). Mexico is reported as the insect’s center of origin. Corn leafhopper has been associated with maize since its domestication around 9,000 years ago. Corn leafhoppers move northward by wind-aided movement from Mexico, where corn is in continuous production all year round. While reproduction is known only to occur in corn, adult corn leafhoppers are known to overwinter in grasses such as wheat, alfalfa, Johnson grass, sorghum, sugar cane, soybean, millet, and gamma grass. As temperatures warm and corn becomes available, adult corn leafhoppers will move into the whorls of developing corn plants.

Figure 3. Geographic distribution of the corn leafhopper, Dalbulus maidis. Image courtesy Pozebon et al. 2022.

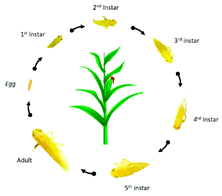

Corn Leafhopper Lifecycle

Corn leafhoppers reproduce only in corn. Females will lay eggs in the leaf tissue of corn plants and are not visible to the naked eye. Corn leafhopper will emerge from the egg and progress through 5 nymphal instars before fully developing wings and becoming an adult (Figure 4). Nymphs will emerge in 2.5 days in temperatures of 80-90°F. At 80-90°F, corn leafhoppers will complete development in just days, with development occurring more rapidly at warmer temperatures. Adults can survive between 30-78 days, with females ovipositing an average of 15 eggs per day for the majority of their adult life, lending to rapid increases in population.

| Image | Caption |

|---|---|

|

Figure 4. Lifecycle of the corn leafhopper. Photograph courtesy Tara-Kay L. Jones, Corteva Agriscience. |

Corn Leafhopper Damage

These insects can impact corn health and yield in two: 1) due to feeding and 2) through transmission of pathogens that cause corn stunt. Corn leafhopper nymphs and adults feed directly on the corn plant by sucking the nutrients. In heavy corn leafhopper infestations, it is not uncommon for the leaves of corn plants to turn dry. Due to the small size of the insects, often what draws one’s attention to a problem is the shiny appearance of leaves due to the corn leafhoppers excreting honeydew as they feed. The development of honeydew can lead to black sooty mold, which can impede photosynthetic processes and negatively impact plant health (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Corn leafhoppers will secrete honeydew that can turn into black mold, as shown on this corn leaf. Photograph courtesy Stephen Biles, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension.

The disease: Corn stunt

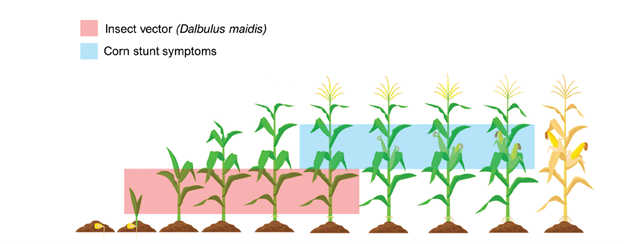

Although the corn leafhopper causes direct feeding injury to corn plants, this insect is a highly efficient vector that transmits three pathogens associated with corn stunt. Two of them are bacterial, corn stunt Spiroplasma (CSS) and maize bushy stunt phytoplasma (MBSP), and one is a virus, maize rayado fino virus (MRFV). The transmission of those pathogens (singly or in combination) has been reported in all corn-producing regions where the corn leafhopper is present. Although the infestation by the corn leafhoppers usually begins at the early crop stages, and the transmission of the pathogens occurs in the vegetative growth stages, symptoms of corn stunt disease only appear later in the season, generally 30 days after leafhopper feeding, when corn has already reached the reproductive stages (Figure 6).

Corn stunt symptoms begin with chlorosis and/or reddening of leaf tips, followed by the production of axillary buds, tillering, plant size reduction, and spike and grain deformation. The resulting disease causes severe stunting of corn plants due to the shortening of internodes and the production of multiple small ears with missing kernels (Figure 7). Yield losses caused by corn stunt are heavily influenced by the corn hybrid and the aggressiveness of the pathogens causing the disease. Since both bacterial pathogens (CSS and MBSP) usually occur together in infecting corn plants and produce similar chlorotic stripes on corn leaves, laboratory techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are needed to diagnose field samples precisely.

Although the 3 pathogens (2 bacteria and 1 virus) can be found together causing the disease, the bacterial pathogen, Spiroplasma kunkelii, has been reported as the predominant pathogen associated with corn stunt. The corn leafhopper can pick up the bacterial Spiroplasma kunkelii in mere minutes of feeding on an infected plant. The pathogen will replicate inside the corn leafhopper’s gut for around 3 weeks before it can transmit the pathogen to a plant. The infected corn leafhopper can transmit the pathogen for up to 1.5 months. Once the corn leafhopper inoculates the corn stunt pathogens inside the corn plants, the pathogens colonize the phloem and become active in growing corn tissues (e.g., younger leaves, roots, ears). The rapid pathogen translocation and multiplication within the plant allows for rapid reacquisition by previously uninfected leafhoppers. Besides that, the long-term dissemination of the pathogens by the corn leafhoppers makes it harder to control using traditional methods.

Figure 6. The corn leafhopper will infect the plants with the corn stunt pathogens during the vegetative stages (in red) while feeding on the plants. Corn stunt symptoms are expressed later in the season when corn reaches the reproductive stages (in blue). Image courtesy Pozebon et al. 2022

| Image | Caption |

|---|---|

|

Figure 7. A) Symptoms of chlorotic stripes that extend towards the leaf tips. |

|

Figure 7 B) Symptoms of reddening leaves and severe stunting due to the shortening of internodes.

Photographs by Maira R. Duffeck. |

Corn Leafhopper Management

There is no established economic or action threshold for this insect in Oklahoma due to this being the first season the insect and disease have been documented in the state. Studies have attempted to control the spiroplasma responsible for corn stunt disease but have not been fruitful. Due to this disease and insect’s low occurrence, corn hybrids have not been developed for the U.S. The best suggestion for managing corn leafhopper damage is planting corn early in the season to allow corn plants to develop and mature before the insect vector and pathogen arrive in the system and impact yield. Below are some suggestions for different forms of control based on recent literature and current understanding of the insect vector and pathogens involved.

Cultural Control: Early planting of corn is advised as leafhopper infestations, and corn stunt disease will increase as the season progresses. Removal of volunteer corn plants following the growing season is also advised to reduce overwintering sites for adult corn leafhoppers. According to the University of California’s Agriculture Natural Resources Integrated Pest Management Program, in no-till systems, when corn is planted as a double-crop following wheat or barley, residue has been shown experimentally to reduce the incidence of both the corn leafhopper and corn stunt disease. However, more research is needed before this strategy can be proposed as a general management tool.

Chemical Control: Corn stunt disease incidence will not be reduced by insecticide control. If you see disease symptoms in the field, the plants have already been infected. Infected plants will not show symptoms for 1 month. If the corn is mature enough, then infection may not impact corn kernels. According to Corteva Agriscience, insecticidal seed treatments consisting of imidacloprid and clothianidin can provide control of corn leafhoppers up to the V3 growth stage. After that, plants are susceptible to acquiring the corn stunt pathogens through leafhopper feeding.

While corn stunt disease has been observed in Texas sweet corn in the past, chemical control was not required due to the low percentage of plants that showed symptoms in the field. Insecticide applications conducted this season by Texas A&M AgriLife Extension in the mid-coast region of Texas have shown that aerial pyrethroid applications did not provide adequate control of the corn leafhoppers. However, applications of Sivanto at 7 oz/a by ground at 10 gpa resulted in 80% control of leafhoppers 3 dat (days after treatment). Per Texas A&M AgriLife Extension, insecticides labeled for leafhoppers in corn include: Carbaryl, Pyrethroids, Sivanto, and Malathion. Carbaryl and Malathion are broad-spectrum insecticides that are toxic to bees and other beneficial insects that may support the natural control of the insect. When possible, avoid the use of broad-spectrum insecticides. The use of these insecticides will eliminate most natural enemies.

Once the plant is infected, there is no available treatment for the disease. In South American countries, current practices for chemical control are to spray at the sight of a corn leafhopper, and often, a field is sprayed 5-6 times within a season due to reinfestations. However, this persistent use of chemical control is likely a contributing factor to the increasing spread of corn leafhoppers and corn stunt from the South into North America. Per a Corteva Agriscience study, as few as two corn leafhoppers per plant for one day was enough to compromise an entire corn field. Depending on when feeding by the corn leafhopper begins, successive sprays may be needed due to rapid reinfestations. The cost of control with repeated sprays, as is practiced in South America, may outweigh the economic loss of yield. Much is to be learned about how this insect and disease impacts corn in Oklahoma and the U.S. should outbreaks be more frequent.

Prior to this year, the last documented outbreak of corn leafhoppers in Texas was in the lower Rio Grande Valley in 2016. This is a new pest and disease in Oklahoma. Oklahoma State University Extension Specialists will monitor the corn leafhopper and associated corn stunt pathogens so that producers, agricultural consultants, Extension Educators, and Specialists can be notified of corn stunt disease potential in future growing seasons. OSU is working to learn more about the insect, pathogens, diseases, and their impact on corn so future guidance can be provided.

Corn stunt Management

Currently, no curative strategies are available to manage corn stunting disease by directly targeting the pathogens infecting the plant. Management programs must rely on agricultural practices aimed at suppressing the insect vector (described in the previous section) within a regional landscape, thus indirectly controlling the pathogens. The early growth stages of corn plants (around 40 d after emergence) are critical for protection against the corn leafhopper due to the long period required for the pathogens to multiply within corn plants and reach levels that can threaten corn production. Insecticide applications are not recommended after the plants reach growth stage V8, as the corn stunt pathogens transmitted from this point onward will not have enough time to multiply within the plants and affect corn yield before physiological maturity is reached. In general, the earlier corn plants are infected with corn stunting pathogens, the more yield is reduced. It’s worthwhile to emphasize that the ability of the corn leafhopper to cover long distances (at least 12 miles) via wind currents demands a joint effort from all corn growers within a regional scale for any management strategy to be effective. We also know that corn leafhoppers evolved in close association with tropical corn hybrids, which are generally more resistant to corn stunt pathogens than the ones planted in temperate regions. Thus, further studies are necessary to screen the corn germplasm in the U.S. for disease tolerance.

References

Himes, S. (2024) Insect pressure remains intense, corn leafhopper reach expanding. AgriLife Today: Farm and Ranch. https://agrilifetoday.tamu.edu/2024/07/23/insect-pressure-remains-intense-corn-leafhopper-reach-expanding/. Accessed: August 7, 2024.

Jones, T-K.L. and R.F. Medina. (2024) Corn Stunt Disease: An Ideal Insect–Microbial–Plant Pathosystem for Comprehensive Studies of Vector-Borne Plant Diseases of Corn. Plants. 9. doi: 10.3390/plants9060747.

Tsai, J.H. Corn Leafhopper, Dalbulus maidis (Delong and Wolcott) (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae). In Encyclopedia of Entomology; Capinera, J.L., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 1072–1074.

University of Florida. (n.d.) Corn Leafhopper: Dalbulbus maidis, Cicadellidae. Florida Corn Insect Identification Guide. https://erec.ifas.ufl.edu/fciig/frleadm.htm. Accessed: August 7, 2024.

Pozebon, H. et al. (2022) Corn Stunt Pathosystem and its Leafhopper Vector in Brazil. J Econ Entomol. 115(6), p. 1817-33. doi:10.1093/jee/toac147.

Biles, S. (2024) Leafhoppers in Corn: Update. Texas A&M AgriLife Mid-Coast IPM. https://agrilife.org/mid-coast-ipm/leafhoppers-in-corn-update/#:~:text=There%20is%20not%20a%20recommended,around%2050%2D100%20per%20leaf. Accessed: August 7, 2024.

Tadeau Arantes, J. Study explains how a fungus can control the corn leafhopper, an extremely harmful pest. Phys.org. https://phys.org/news/2024-03-fungus-corn-leafhopper-extremely-pest.html. Accessed: August 7, 2024.

UC IPM. Agriculture: Corn Pest Management Guidelines – Corn Leafhopper, Diabulbus maidis. (2006) https://ipm.ucanr.edu/agriculture/corn/corn-leafhopper/#gsc.tab=0. Accessed: August 7, 2024.

Jeschke, M. (2024) Field Facts: Corn Stunt Disease in the U.S. Pioneer agronomy sciences. 24:2.