Asian longhorned tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis, in Oklahoma – Aug. 7, 2024

The Asian longhorned tick (ALT), (Haemaphysalis longicornis Neumann) (Figure 1), has recently been identified from cattle in Mayes County, in northeast Oklahoma.

Figure 1. An adult female Asian longhorned tick (ALT) (Haemaphysalis longicornis). Photograph by J.A. Cammack.

Distribution

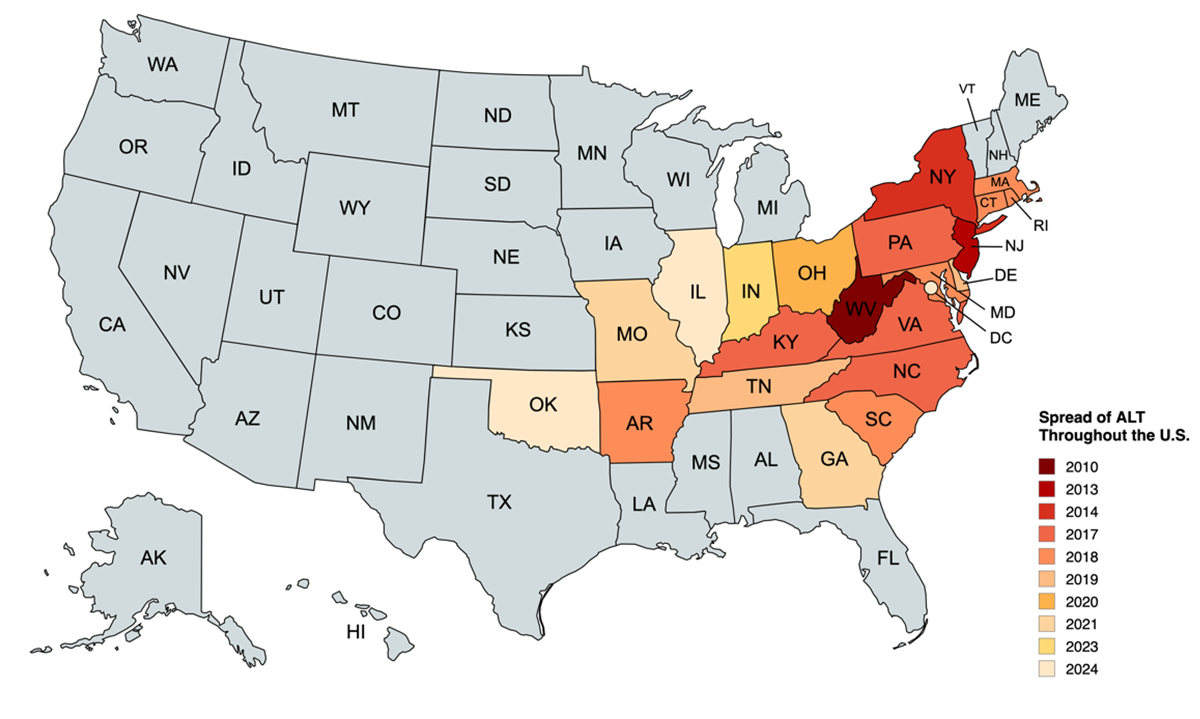

The species is native to East Asia, including China, Japan, Republic of Korea, and southeast Russia, and has been introduced to Australia, New Zealand, several Pacific Islands, and the U.S. The species was first reported in 2017 on an infested sheep in New Jersey(1), but identification of archived samples has revealed the species was present on white-tailed deer in West Virginia as early as 2010, and on a dog in New Jersey as early as 2013(1,2). Since that time, ALT has spread south and west across the United States, and is now known to occur in 21 states and Washington, D.C. (Figure 2), in 259 of the 1,462 counties within this range.

Temperature, humidity, and rainfall are the most important environmental factors regulating the distribution and spread of the species across North America. Central Oklahoma (approximately the I-35 corridor) is at the western edge of the predicted range of the species(3). Because a significant portion of the tick’s life (90%) is spent in the environment off of the host, the low humidity and soil moisture in the western portion of Oklahoma are likely to result in dehydration of the ticks, and limit the likelihood of establishment in these drier areas of the state.

Figure 2. Distribution of the Asian longhorned tick (ALT) (Haemaphysalis longicornis) within the United States, and year of first documentation. Created with www.mapchart.net.

Description and Biology

Asian longhorned ticks are three-host ticks, and can be found feeding on many species of animals, ranging from wildlife (birds to mammals), to pets (dogs and cats), to livestock (sheep, goats, horses, and cattle); to date, ALT has been collected from nearly 150 host species, including humans(2). They are light brown to reddish brown in color (Figure 1) and are very small, approximately the size of a sesame seed. The mouthparts are short and broad, resulting in a distinct, pentagonal shape of the head when viewed from above, that is characteristic of this group of ticks.

Populations of this species that have been documented in the U.S. are able to reproduce asexually (i.e. without mating), through a process known as parthenogenesis. Females can lay over 3,000 eggs, and development from egg to adult occurs in as little as 82 days at temperatures between 26-28°C (78-82°F)(4). Their unique reproductive strategy (reproduction without mating) and high rate of reproduction are characteristics that can lead to large populations occurring in the environment or on animals in a relatively short period of time.

As a three-host tick, the immature life stages (six-legged larva, eight-legged nymph) will attach to a host, bloodfeed, and drop off the host to digest the meal and molt to the next stage, and eventually to an adult. During this time of digesting and molting, the ticks will rest in protected areas with higher humidity, such as leaf litter and the thatch layer of grass. Over 90% of a three-host tick’s life is spent off of the host. Once molted to the next life stage, the ticks will then climb back up vegetation (grasses, shrubs) and wait for a host animal to pass by. Although the immature life stages will typically feed on smaller animals than the adult, all life stages have been found feeding together on the same host species.

Pest Concern

The ALT is of particular concern for livestock, especially cattle. Tick populations on cattle can become so numerous that the animals become stressed, lose weight, reduce milk production, become anemic, and in some cases, die. Animals should be monitored for any changes in behavior or body condition, and if changes are noted, should be inspected for the presence of ALT. Of greatest concern regarding the ALT and cattle is the tick’s ability to transmit the pathogenic Ikeda genotype of Theileria orientalis to cattle (cattle theileriosis). Symptoms are similar to anaplasmosis, including fever, anemia, pale coloration of the mucous membranes, and weakness. More advanced infections can result in jaundice, abortion, and even death of the animals. However, at the current time, the pathogenic Ikeda genotype of Theileria orientalis has not been documented in Oklahoma.

Additionally, under laboratory conditions, ALT is a competent vector of numerous pathogens that can cause disease in humans, including Rickettsia rickettsii (Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever)(5), Heartland Virus(6), and Powassan Virus(7).

Protection and Prevention

Currently, the best method to protect people, pets, and livestock is to limit the likelihood of contact with ALT. When outdoors or working with animals, wear permethrin treated clothing or general insect repellents. Protect pets with products approved for tick control; consult your veterinarian for approved products. For livestock, limit the movement of animals between farms/locations, and thoroughly inspect any new animals that are brought into a herd. Pesticides labeled for the control of ticks on cattle, coupled with cultural control (keeping grass mowed and brush cleared) and reducing the movement of animals, can help form the basis of an integrated pest management program for Asian longhorned tick(8).

If you suspect that your animals may be infested with Asian longhorned tick, contact your veterinarian and/or county extension office. Additionally, specimens can be collected in sealed containers such as a Ziploc bag or small water bottle; a glass vial containing 70% ethanol is the best method. If submitting samples in any container other than a glass vial, the specimens should be submitted dry/without preservative solution. Samples should be submitted for identification to the Oklahoma Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory using the General Submittal Form. In the History section, indicate “Asian Longhorned Tick ID”, and be sure to include: the address of where the tick was found, the date collected, and the host the tick was collected from (i.e. cattle, dog, etc.). Samples can be sent to:

Oklahoma Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory

1950 W. Farm Road

Stillwater, OK 74078

References

- Bajwa, W. A. Kennedy, Z. Vincent, G. Heck, S. Riaj, Z. Shah, L. Tsynman, C. Castal, S. Haynes, H. Cornman, A. Egizi, E. Stromdahl, and R. Nadolny. 2024. Earliest records of the Asian longhorned tick (Acari: Ixodidae) in Staten Island, New York, and subsequent population establishment, with a review of its potential medical and veterinary importance in the United States. Journal of Medical Entomology 61(3): 764-771. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjae019

- National Haemaphysalis longicornis (Asian longhorned tick) Situation Report. July 31, 2024. United States Department of Agriculture. Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service.

- Rochlin, I. 2019. Modeling the Asian longhorned tick (Acari: Ixodidae) suitable habitat in North America. Journal of Medical Entomology 56(2): 384-391. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjy210

- Hoogstraal, H. F.H.S. Roberts, G.M. Kohls, and V.J. Tipton. 1968. Review of Haemaphysalis (Kaiseriana) longicornis Neumann (Resurrected) of Australia, New Zealand, New Caledonia, Fiji, Japan, Korea, and Northeastern China and USSR, and its parthenogenetic and bisexual populations (Ixodoidea, Ixodidae). The Journal of Parasitology 54(6): 1197-1213.

- Stanley, H.M. S.L. Ford, A.N. Snellgrove, K. Hartzer, E.B. Smith, I. Krapiunaya, and M.L. Levin. 2020. The ability of the invasive Asian longhorned tick Haemaphysalis longicornis (Acari: Ixodidae) to acquire and transmit Rickettsia rickettsii (Rickettsiales: Rickettsiaceae), the agent of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, under laboratory conditions. Journal of Medical Entomology 57(5): 1635-1639. https://www.doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjaa076

- Raney, W.R. J.B. Perry, and M.E. Hermance. 2022. Transovarial transmission of Heartland Virus by invasive Asian longhorned ticks under laboratory conditions. Emerging Infectious Diseases 28(3): 726-729. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2803.210973

- Raney, W.R. E.J. Herslebs, I.M. Langohr, M.C. Stone, and M.E. Hermance. 2022. Horizontal and vertical transmission of Powassan Virus by the invasive Asian longhorned tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis, under laboratory conditions. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 12: 923914. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.923914

- Butler, R.A. and R.T. Trout Fryxell. 2023. Management of Haemaphysalis longicornis (Acari: Ixodidae) on a cow-calf farm in East Tennessee, USA. Journal of Medical Entomology 60(6): 1374-1379. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjad121